by Gideon Marcus

The history of our genre, like that of all things, contains several ups and downs. From its beginnings in the pulp explosion, to its near-extinction during the second world war, to the resurgence during the digest age starting in the late '40s, and finally, to its decline at the end of the last decade. At its most recent nadir, the number of science fiction periodicals had dropped to six from a high of forty. Many predicted the imminent death of the genre, and not without justification.

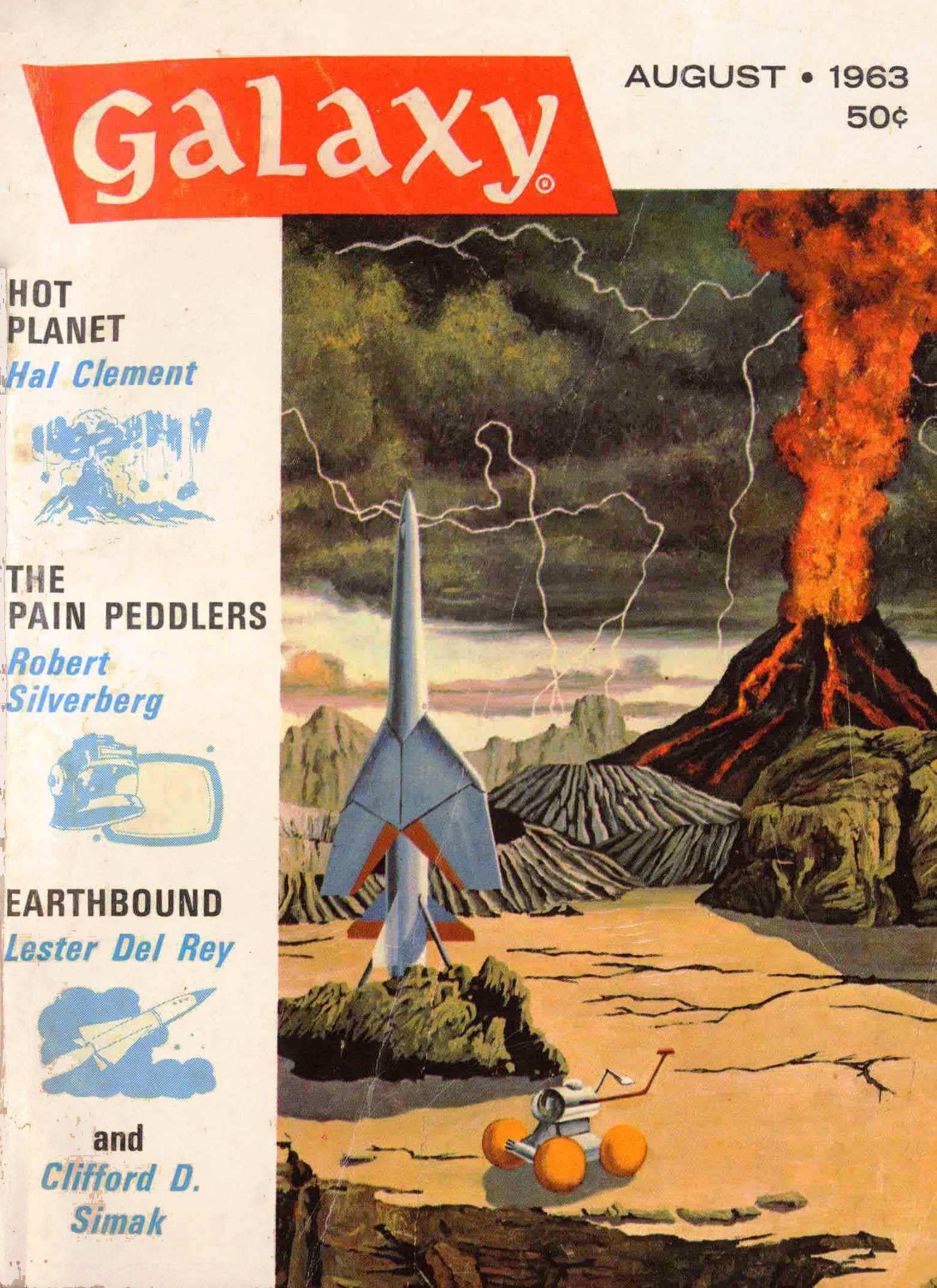

1963 may well be remembered as the year things turned around. In February, Worlds of Tomorrow was introduced as a sibling to sister magazines, Galaxy and IF. To all accounts, it is a successful venture. And last month, another digest joined the throng.

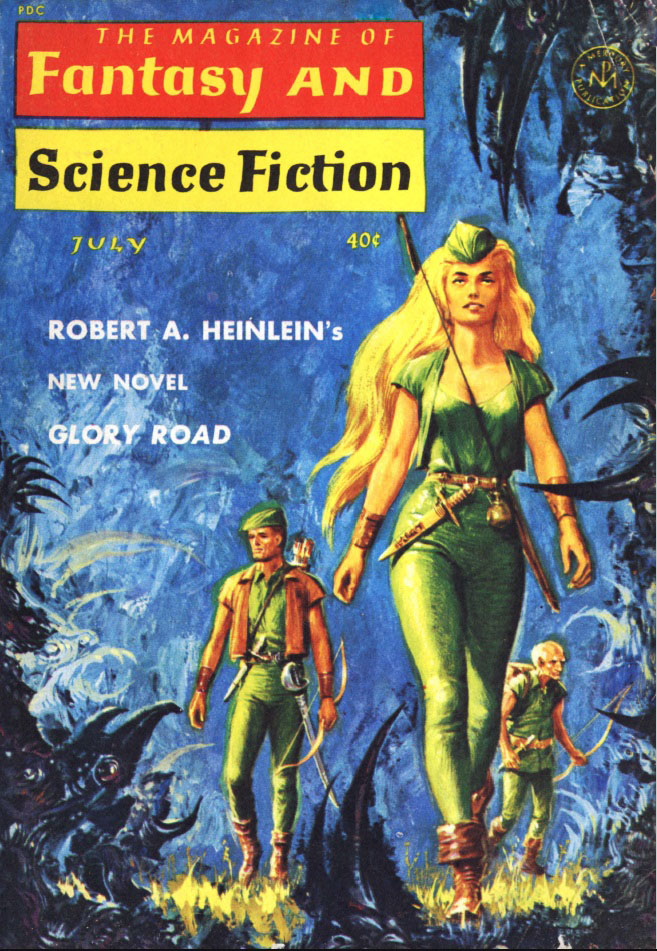

Back in 1949, the digest boom was kicked off by the birth of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. It was, in many ways, a repudiation of the pulp genre, or perhaps a sign of its maturation. F&SF set its literary standards bar very high, filling its pages with some of the most articulate works and authors our field has seen (and, with some hiccoughs, continues that tradition to this day). For fourteen years, it stood unique in SFF. This is not to say that other magazines did not approach or even surpass it in quality, but the combination of breadth of subject matter and eloquence of presentation made it a creature unto itself.

Until now.

The newest SFF mag is called Gamma, and here's how its editor, Charles E. Fritch, introduces it:

The Dictionary defines GAMMA for us: "…to designate some bright star." One look at our cover and at the stunning lineup of stellar names for our next issue will confirm that definition. Indeed, GAMMA is the bright new star of the science fiction/fantasy field, and we intend to see that it continues to light up the heavens. The dictionary goes on to mention the gamma function — and we'll assure you that the GAMMA function, in our case, is to give our readers the best fiction, by the finest talents in and out of the sf field — fiction of yesterday, today, and tomorrow. GAMMA will unearth classic fantasy from obscure, out-of-print markets, while creating its own classics and memorable stories in each issue.

Ambitious, to be sure. For those of us who remember the arrival of F&SF, we cannot help note the similarities of the two magazines. The style and composition of the sole piece of art (and the fact there is just one throughout the whole book) is highly reminiscent of the older digest. Inside, too, there are sixteen pieces, none longer than twenty pages. The majority of the listed authors have had work published in F&SF, too.

Just as F&SF has "theme" issues, this "FIRST BIG ISSUE" of Gamma has a clear The Twilight Zone angle. All five of the anthology show's main authors have a piece in the mag, and Rod Serling gets top (or, I suppose it can be argued, bottom) billing.

But does this F&SF doppleganger live up to the standards of its predecessors? You'll have to read it and find out (hint: You won't be disappointed):

Mourning Song, by Charles Beaumont

Beaumont is one of the "Zone's" most prolific guest writers, and his pieces are generally marked with authorial expertise. He is, in many ways, what Bradbury should be: Emotional without being mawkish; literate without self-indulgence. Mourning Song, about a sightless old bard who claims to know when death is coming, and the young man who dares to disbelieve, is one of the most poignant things I've seen Beaumont produce. Five stars.

Crimes Against Passion, by Fritz Leiber

The damned in hell get a chance to re-plead their cases, with the help of a psychiatric public defender and the burgeoning field of Analysis. It's meant to be a funny piece, but largely fails at comedy (save for one genuinely funny line, when Macbeth shouts irritably at his former adversary, "Lay off, MacDuff!") Lieber's been hit or miss lately, and this is a definite miss. Two stars.

Time in Thy Flight, by Ray Bradbury

A reprint from the July 1953 Fantastic Universe, this tale of young time travelers from an antiseptic future, and the girl who decides to stay in 1928, is played for every sentimental note. Brush your teeth afterwards. Three stars.

The Vengeance of Nitocris, by Tennessee Williams

Now here's an interesting one, the very first sale of arguably the world's greatest living playwright. This tale of a vengeful Egyptian Empress of the Old Kingdom first appeared in the August 1928 Weird Tales. It's nothing if not lurid, and the story it tells is a true one (or, at least, attested back to ancient times — I checked the sources cited). Three stars.

Itself, by A. E. van Vogt

A robotic anti-sub is the star in Van Vogt's aquatic answer to Laumer's sentient tank story, Combat Unit. Just not as good. Two stars.

Venus Plus Three, by Charles E. Fritch

A disenchanted wife brings his husband to savage Venus so that man-eating plants can preclude the need for a messy divorce. An outdated, pulpish tale, but still entertaining. Three stars.

A Message from Morj, by Ray Russell

The pulsing from the distant world could be none other than a communication — but just what was it trying to say? This vignette manages to be, by turns, both surprising and predictable. Three stars.

To Serve the Ship, by William F. Nolan

When your occupation has been to be sole pilot of a starship for eight decades, it can be pretty hard to adapt to retirement. Author Nolan takes on a subject that both James White (Fast Trip) and Anne McCaffrey (The Ship Who Sang) have handled better. Three stars.

(And now, you may be thinking, "With the exception of the Beaumont, this doesn't sound like a great magazine." Fear not. It's all gravy from here.)

Gamma Interview: Rod Serling, by Rod Serling

Any conversation with one of television's brightest lights is bound to be an engaging one. The Twilight Zone's creator does not disappoint. Five stars.

The Freeway, by George Clayton Johnson

Johnson is another Zone regular, and in this tale of the breakdown of an automatic car in the middle of the desert, he highlights the danger of over-reliance on technology. Could you survive? Not just the physical peril, but the knowledge of just how ill-equipped we are to deal with nature undiluted? A solid three stars.

One Night Stand, by Herbert A. Simmons

Horn-blowing misfit finds his groove and love in a gig on the Red Planet. The first SFF story I've read by a Black man (that I know of), it's a satisfyingly hep read. Three stars.

As Holy and Enchanted, by Kris Neville

I first fell in love with a fictional character when I was ten. It was Polychrome, the fairy daughter of the rainbow who first fell to Earth in The Road to Oz, and I wrote several childish tales that detailed our meeting and (innocent) courtship. This reprint from the April 1953 Avon Science Fiction and Fantasy Reader covers similar ground, but far more beautifully than I ever could have managed. Four stars.

Shade of Day, by John Tomerlin

A sick salesman whose life zagged when it should have zigged revisits the last happy time of his life, touring the Junior High of his early teens. Heavy, subtle, effective. Four stars.

The Girl Who Wasn't There, by Forrest J. Ackerman

If you don't yet know 4E, that legendary SFF fan who helms magazines, anchors conventions, and keeps old magazines in his refrigerator for want of space elsewhere, this tale of a lonely, invisible girl is a good introduction. Four stars.

Death in Mexico, by Ray Bradbury

I spend much of my time praising Bradbury with faint damns, but this poem is a genuinely worthy piece. Four stars.

Crescendo, by Richard Matheson

It's never a bad idea to wrap up a magazine with Matheson, possibly the best SFF screenwriter of our age. Who else could make an electric church organ so plausibly menacing? Four stars.

Viewed with the dispassionate eye of a statistics collector, GAMMA garners a strong, but not noteworthy, score of 3.4 stars. Taken as a whole, however, this is a stunning first issue. For those who like F&SF and wish there were more magazines like it, your prayers have been answered. Here's looking forward to GAMMA 2, coming out in the fall.