by Mark Yon

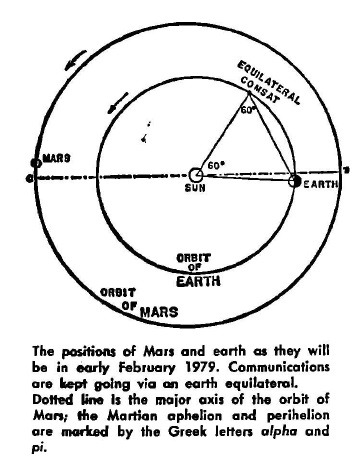

Scenes from England

Hello. Testing, testing.. Anyone there?

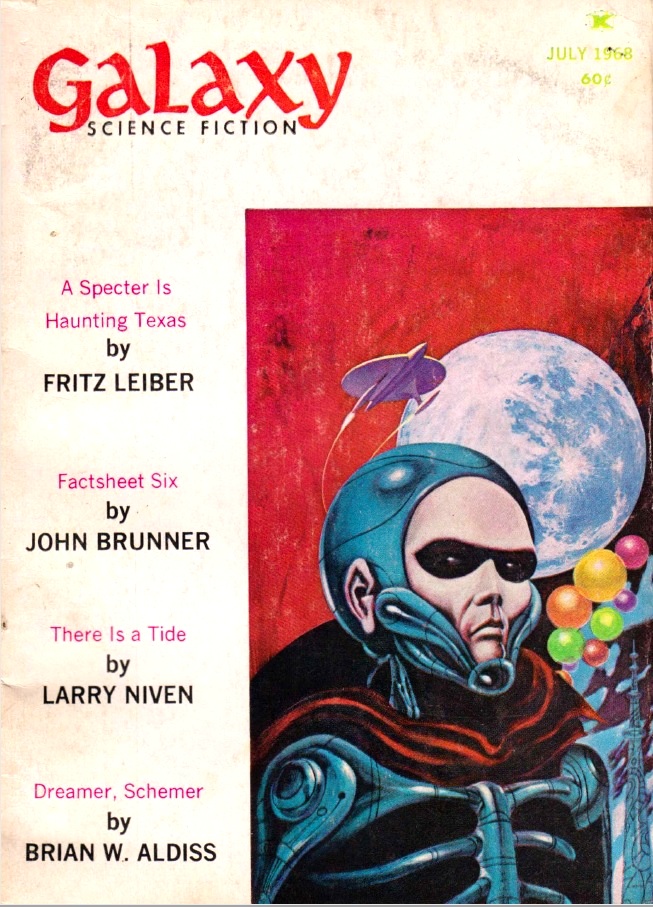

This feels a little like one of those lonely messages out on the ether, post-apocalypse. I was last here for the July 1968 issue, whose publication, if you remember, was at a time of turmoil…. And then nothing for nearly four months.

Until now, when, like the proverbial British buses, two turn up (nearly) at once.

So – let’s start with the October issue.

I can only assume that the late arrival of the October issue was in part because of the recent kerfuffle. Editor Mike Moorcock explains the situation in this issue (and which you can read about in more detail in my last review), that with the effective banning of sales in English newsagents New Worlds is to survive mainly on subscriptions in the future, with a dollop of cash from the Arts Council, admittedly.

To Moorcock’s credit, he doesn’t dwell on the matter. But this whole issue feels like a statement of intent and a possible return to what I would regard as ‘normal’ – for New Worlds, anyway. It’s now being published from a new address, for one thing.

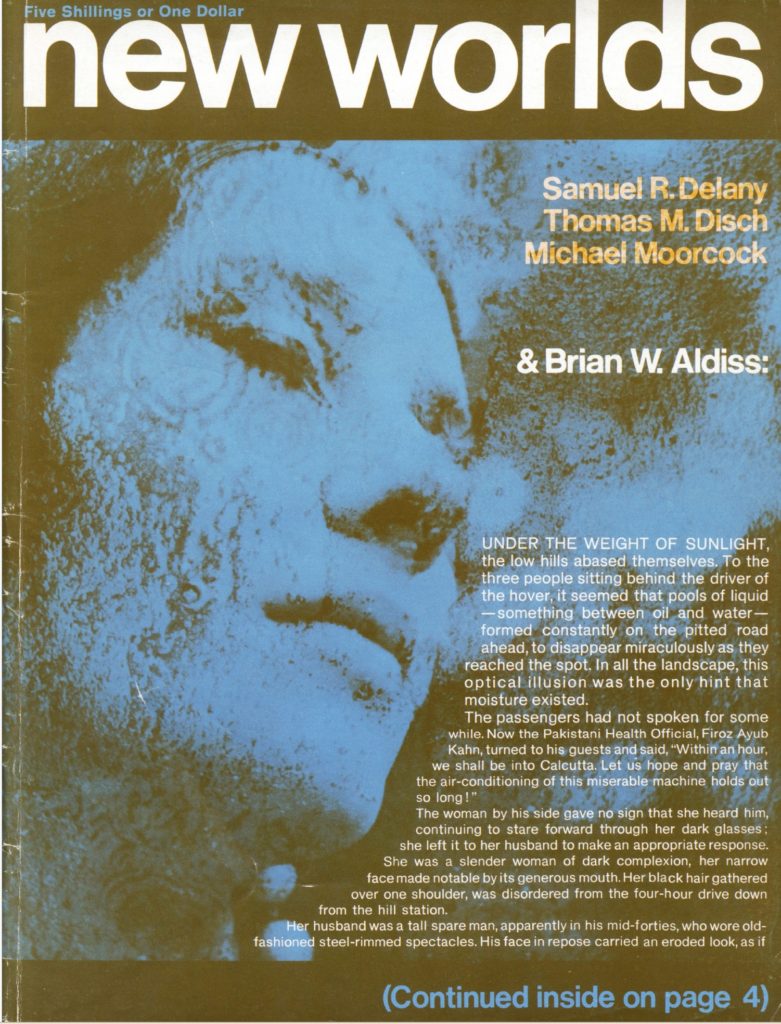

Cover by Malcolm Dean

Cover by Malcolm Dean

And that ‘return’ seems to be echoed in the cover, too. Thank God – a ‘proper’ cover illustration. You know, with a picture, and something that looks like it’s taken more than ten minutes to produce. Whilst I could argue that it’s not the most complex piece of artwork ever shown – and a tad on the gory side – at least it is what I would regard as art.

Lead In by The Publishers

Some changes here too. Editor Mike Moorcock has brought readers (those of us who are left, anyway) up to date with what has been happening in the Lead In, even if some kind of strange time warp has happened as the Editor claims that his comments were made “last month” and not actually in the April issue. Readers with a good memory and less impacted by this may remember when Moorcock promised more pages and pictures in colour – clearly now that isn’t going to happen.

Other than that, the usual descriptions of the authors and their explanations of their stories, for those of us too unintelligent to work it out for ourselves.

Disturbance of the Peace by Harvey Jacobs

Disturbance of the Peace by Harvey Jacobs

Do you remember The Shout? in the last issue? (I know, but it’s been a while.) Disturbance of the Peace reminded me a little of that, as it is an observational piece about I’m not sure what.

The story is focused on Floyd Copman, set in a fairly contemporary Manhattan. Floyd has a pretty mundane job in a bank, where in amongst the dull details of a day we find that Floyd is being watched by a dishevelled customer, who spends all of his day staring at Floyd. It becomes a bit of an obsession, and despite multiple attempts to remove him the situation inevitably ends up with the man’s return. It is quite unnerving for Floyd, and eventually results in both the old man having a fit and Floyd fainting.

What’s the point of the story? There’s lots of description of the city Floyd travels in and the things he sees, not to mention things happening around Floyd – the descriptions of his co-workers are supremely awful – and yet it all seems to be of little purpose. It’s more of a mood piece to me, but at its best it reminded me a little of John Brunner’s work. 3 out of 5.

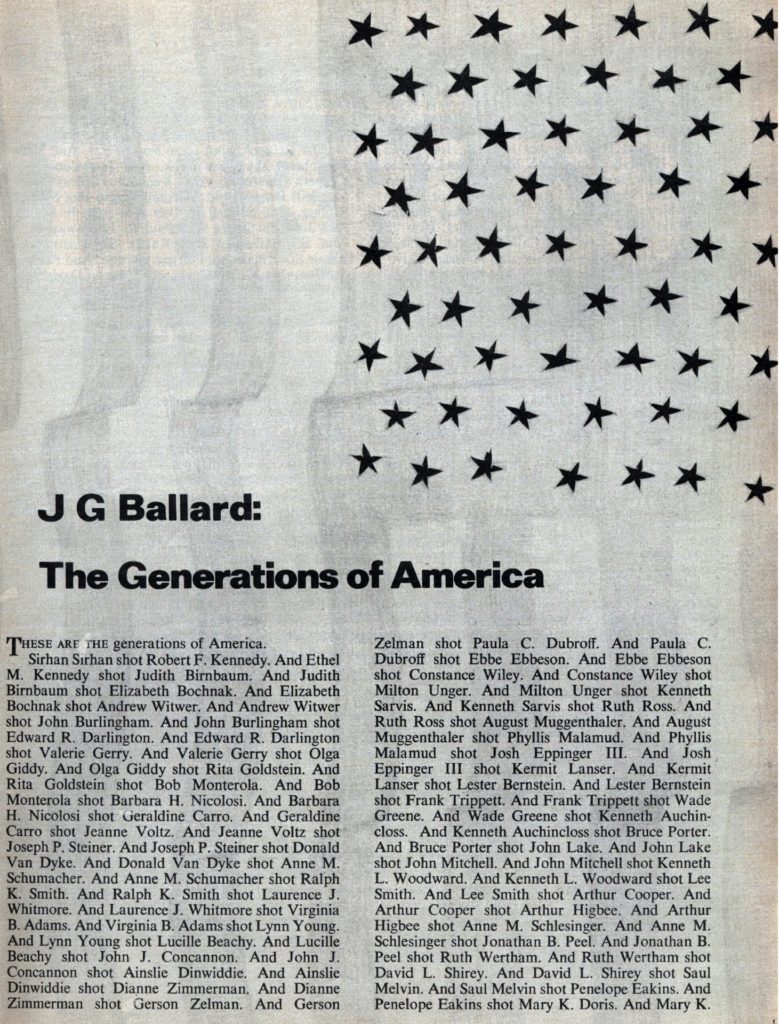

The Generations of America by J. G. Ballard

"Sirhan Sirhan shot Robert F. Kennedy. And Ethel M. Kennedy shot Judith Birnbaum."

In which Ballard lists, in huge blocks of continuous text, people shot by other people.

I don’t know if all the names mentioned are real, although I have no evidence to suggest that they are not – there are some such as Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, but the rest could easily be made up – but if the point is that lots of people have been shot in America, the point is made. Whilst the very, very long list makes the point that far too many people are shot, the purpose of the prose may also be to highlight the fact that many of the shootings that happen in the US are to people of whom we know nothing. They should be remembered, and it is perhaps an indictment of society that most of them are not.

The issue for me is that not only do I find reading long lists difficult, the block of text as presented is difficult to focus on – which I accept may be the purpose of the prose. It shows that Ballardian thing of repetition, after all – something he – repeats – often in his work.

But this feels like a Ballard clutching at straws, even if this is Ballard again riffing off American culture, and not in a good way. Is it fiction? I don’t know. It makes a good point, admittedly, but I think it is less exciting, less meaningful than his work from before, and weaker as a result. 3 out of 5.

Bubbles by James Sallis

If you’ve read my previous reviews, you may know that newly-appointed Associate Editor Sallis has been foisting much poetry upon us readers lately – something I’ve not appreciated. Happily then, this is a prose piece, and rather like Disturbance of the Peace it’s good on observational description, but this time about London. As we get all these lyrical sentences, the plot, such as it is, is about remembering someone – Kilroy – who is about to die. A story thus of a life lived and the places they frequented before showing us that life moves on. 3 out of 5.

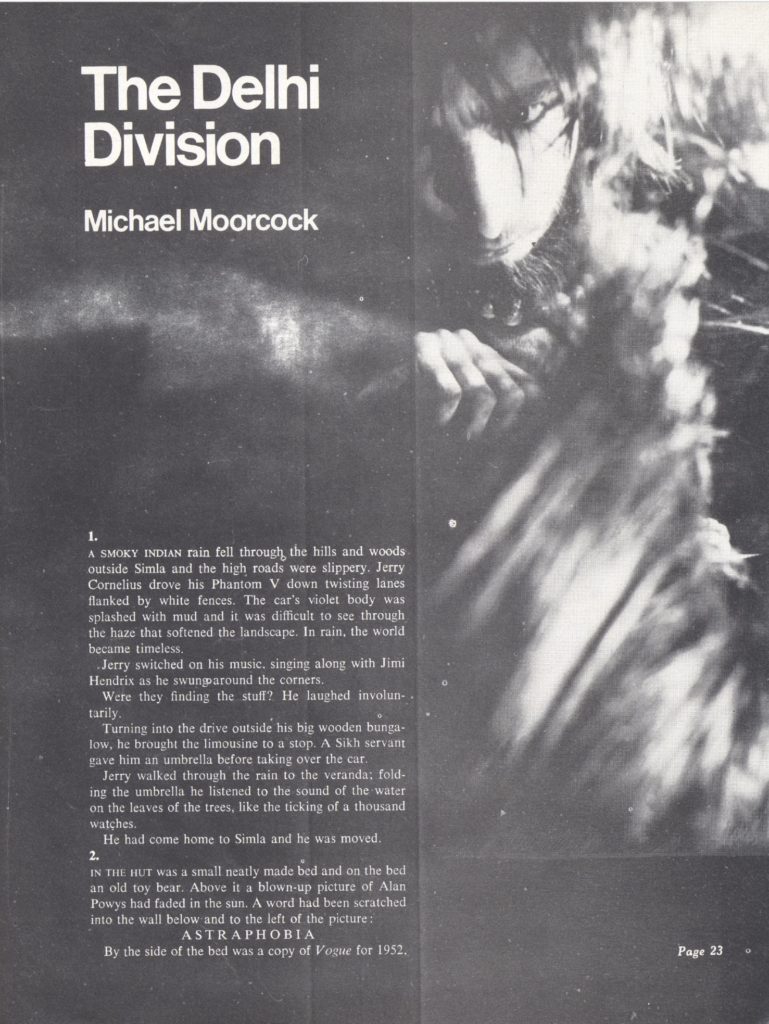

Article: Into the Media Web by Michael Moorcock

Article: Into the Media Web by Michael Moorcock

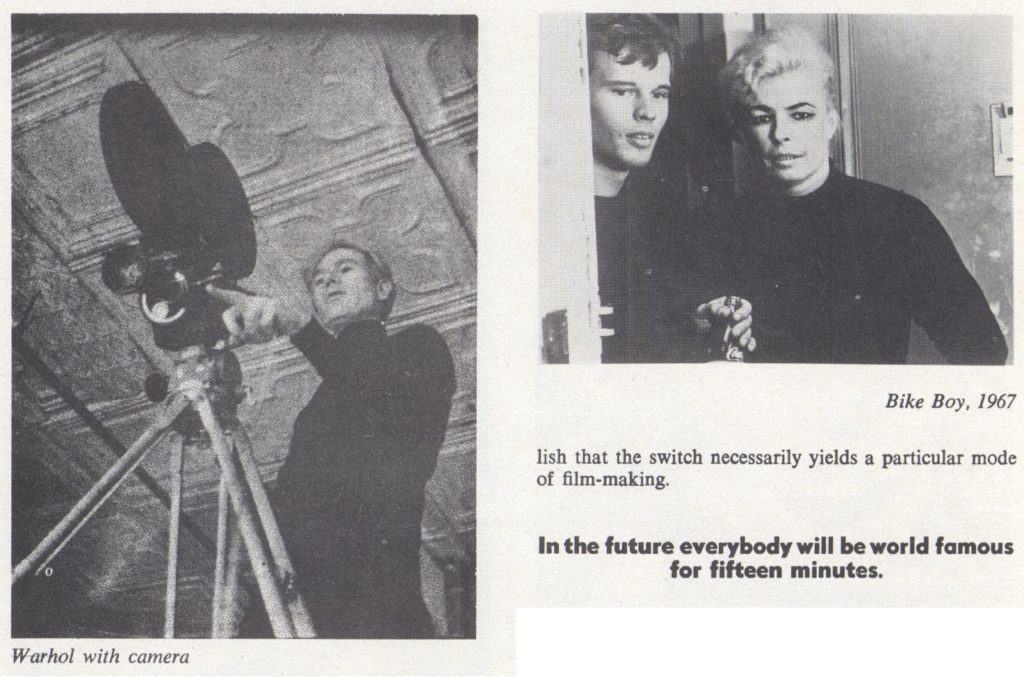

An interesting article about how all media – audio, visual and print is interconnected like a spider’s web. Mike explains that future media will show an improvement in quality but at the same time have a lowering of standards in order to ensure mass appeal and remain commercial. How we manage a balance between all of this will be an important point in the future.

I can’t say I disagree.

Moorcock then manages to make his point using the analogy of Westerns and how they were important as printed stories, became less popular but have now been resurrected by returning to their core values through the medium of television. It shows the relative complexity of the interrelationships between media. Is this article inspired by the recent troubles here at New Worlds? Well, possibly, except that it is an extract from a longer article, and therefore possibly written before the furore. It can be said though that it is a reflection on the current state of play in the media, and it may not be coincidence that much of New Worlds' latest difficulties are in part due to Moorcock’s insistence on doing what this article says the media must do – setting new boundaries, of being different and not touting formulaic stuff. This article, like all good articles, was informative and also made me think. 4 out of 5.

Casablanca by Thomas M. Disch

No, nothing to do with the Humphrey Bogart movie. Disch’s story seems to be a satire on Americans abroad, showing us their insularity and pettiness. (We really are having a go at the US this month, aren’t we?) It all begins relatively normally before Mr. and Mrs. Richmond, our hapless Americans, find themselves in Casablanca in the middle of an anti-American demonstration and the unleashing of nuclear weapons, the once powerful now rendered impotent. It’s a compelling example of what happens when insular arrogance created by self-importance suddenly becomes redundant.

With its depiction of Americans lost in another country and befuddled by local customs, Disch's story reminded me of less of the movie Casablanca than the beginning of Alfred Hitchcock’s film, The Man Who Knew Too Much. Talking of Hitchcock, others must think highly of this one too, because I understand the story has recently appeared in one of those Alfred Hitchcock anthologies and is reprinted here. 4 out of 5.

Drawings by Malcolm Dean

by Malcolm Dean

by Malcolm Dean

I expected this section a little, as for the last few issues we’ve had graphic stories in various forms. This feels to me like it is the New Worlds version of Gahan Wilson’s efforts in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction – but as you might expect in a British magazine, darker, and perhaps odder. 2 out of 5.

Biographical Note on Ludwig van Beethoven II by Langdon Jones

Biographical Note on Ludwig van Beethoven II by Langdon Jones

The return of ex-Associate Editor Langdon Jones. Fresh from his publication of the Mervyn Peake Gormenghast material, this story begins like a typical biography (the clues in the title!) of a musician before the reader realises that it is satirical. It has many of the hallmarks expected in Langdon Jones’s usual material – florid language, poetry, musical scores, lyrics and so on. An inventive flight of fantasy, clearly meant to be a satirical musing on the music business and culture at large. I know some readers will like it more than me. For me, a middling 3 out of 5.

Photographs by Roy Cornwall

And again, something that’s been missing from recent issues, those pictures of strange artwork. This new version has buildings with patterns of light and shadow – and of course, a naked lady. No explanation – I guess we are just meant to be inspired – or aroused. 2 out of 5.

And again, something that’s been missing from recent issues, those pictures of strange artwork. This new version has buildings with patterns of light and shadow – and of course, a naked lady. No explanation – I guess we are just meant to be inspired – or aroused. 2 out of 5.

We’ll All Be Spacemen Before We Die by Mike Evans

Ah, poetry. 3 out of 5.

Ah, poetry. 3 out of 5.

Bug Jack Barron (Part 6 of 6) by Norman Spinrad

At last – the final part of this story. It has only taken ten months to get here. (sarcasm inserted – feel free to vent your own frustration here.) Despite taking five parts to get to this point, some of the story is condensed here in the summary, even though it has never been seen before!

Quick recap – In the last part, Henry George Franklin makes a drunken claim on Jack’s TV show that he had sold his daughter to a white man for $50 000. After the show, Benedict Howards, the owner of the Foundation for Human Immortality, demands that Franklin is kept off the air and threatens to kill Barron if he doesn’t. Barron’s response? He goes to visit Franklin in the Mississippi.

After being told the story by Franklin, the two are fired upon. Franklin is killed. Barron is convinced that Howards is behind the buying of the little girl – and more so other mysterious disappearances in the area. He becomes determined to test Howards in his next TV show.

He agrees to meet Howards in Colorado and records the meeting. When Howards admits to killing Franklin, he discovers Barron’s recording. The result is that Barron wakes up in hospital having being made immortal. The secret is out – it is the glands of these young children that create immortality, but they are killed in the process. And Sara has also been treated.

Barron is now part of the process – can he now incriminate Howards on air? On his return to New York, he tells Sara what has happened. They now have a decision to make – does Jack live forever or tell the world and die now?

Before the show goes live, Sara contacts Barron, and after taking LSD tells Jack that she thinks he is not making the decision to attack Howards because of the need to protect her. To solve this, she jumps off Barron’s apartment balcony.

The story then takes up the narrative from here.

With the suicide of media star Jack Barron’s ex-wife, things are now set for a final showdown between Jack and Howards. The death of Sara was in part caused by Howards in an attempt to free Jack from being tied down to Howards.

I don’t think I need to say too much here. Suffice it to say that things are tied up as justice is done and Sara is avenged. If you’ve read all that has gone before, you’ll understand what’s happening. Everyone else? Less so – and perhaps be less inclined to bother.

Perhaps the more important point is: was it all worth it? After all, a story stretching across six issues has to merit some value, surely? I started reading it myself way, way back in November 1967 with some degree of optimism at a new and exciting means of telling a story and by the end am exhausted, willing the story to have departed long before it did. I suspect that reading it as a novel may reduce this feeling a little, but for me after its initial signs of promise it was too much for too long. Let’s also not forget that its publication nearly brought down the magazine as well. It outstayed its welcome, for me. Time will tell if other readers look on it as wearily as I do. Hard to think that at the start I was thinking 4 and 5 out of 5, now it feels more like 3 out of 5.

Time for something new.

Book Review and Comment – Boris Vian and Friends by James Sallis, and the conclusion of Dr. Moreau and the Utopians by C. C. Shackleton

Firstly, James Sallis (remember him?) reviews Boris Vian’s novel Heartsnatcher, translated from the original French by Stanley Chapman. This allows Sallis to quote great chunks of Vian’s text. Unsurprisingly for such an obscure work, Sallis can’t recommend it highly enough. He relates it to work by authors such as Ballard and Thomas Pynchon but also more recent writers here such as Aldiss, Disch, Sladek and Langdon Jones, describing Vian’s book as a new logic of the imagination.

It might gain some interest as a result.

The only other book of note briefly mentioned here is the paperback publication of Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which “has all of Clarke’s virtues well-displayed.” For what it’s worth, I agreed when I reviewed the hardback novel here back in July. There'll be more on this later.

Lastly, we have the conclusion of an article by C. C. Shackleton (aka Brian Aldiss) begun last issue about H. G. Wells’ ideas of utopia. It may be difficult to read without referring back to the earlier, and longer, part, but I followed it easily enough. Unsurprisingly, as Aldiss/Shackleton is a huge admirer of Wells, the article is positive, saying at the end that Wells pretty much started the idea in science fiction that the genre (and therefore much of Wells’ work) is “a study of man and his machines and society’s changing relationship to science and technology.” To which I would add, “Well, yes – him and Jules Verne.” I’m sure there’s others that could be mentioned too.

Summing up the October New Worlds

A big sigh of relief this month. Although the issue is somewhat of a mixed bag and with nothing too controversial, it does feels more like a normal issue of New Worlds, with the usual mixture of allegory and confusion usually engendered by its presence.

Interestingly, although it has always been there in the last few years, this was the first time that I did notice how American (Americentric?) the issue felt. Perhaps it was because it’s been a while since I read a copy, but I really noticed it this time. Is this a consequence of New Worlds now being sold where most of you are? Perhaps. However, with American writers throughout and the prose filled with American characters and places, the quaint old idea of New Worlds being a “British” magazine seems to have gone – even when most of the stories seem to be attacking America satirically or ideologically.

The return of stalwarts like Ballard, even if he has passed his prime, will be a reason to buy this one, although being mainly subscription-based, the magazine may only be preaching to the already-converted.

For me the most memorable item, unusually, was Moorcock’s article. It’s not common for me to be impressed by the non-fiction, but this one really made an impression. The fiction, by comparison, was rather pallid. Nice prose, nothing especially extraordinary. If I was pushed to make a choice, I would suggest that Disch’s Casablanca was the fiction piece I appreciated most.

Most importantly, this issue means the end of Jack Barron, which took a long, long time to get there but finally ended. It is due out in book form fairly soon, I gather – if they can find any bookshop willing to stock it, of course!

The November New Worlds

So just as I was writing up my thoughts on the October issue, the November issue arrived. Looks like Mike and the gang are trying to make up for lost time! The issue is here.

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

One of those images that I suspect only a recreational drug user will understand. A step back from the October issue, I think.

Lead In by The Publishers

The key point here is that Moorcock points out that all of the fiction in this issue is from new writers. I see this raising of potential talent as a good thing, but my more cynical self suspects lower rates were paid. I also suspect greater variability in quality. We will see!

Area Complex by Brian Vickers

Area Complex by Brian Vickers

To the first – the cover story. I liked this one. It’s an account compiled from writings by a number of teenage gang members living in a gang in a future Clockwork Orange kind of dystopia. As you might expect, it is a tough existence, living in decaying cities with lives filled with sex and violence. The group often kills others from rival groups, whilst trying to survive.

The big twist at the end is that the group are a religious sect living in a post-disaster world. This also gives the writer chance to have a pop at religion as is rather expected in New Worlds these days. It doesn’t end happily, but then that’s what we’ve come to expect in these British anti-utopian stories.

What impressed me most was how this story epitomised the New Wave stuff at the moment. If anyone remembers Charles Platt’s Lone Zone back in July 1965 it reminded me of that, but with lots of elements that could be from Aldiss, Ballard, Anthony Burgess (Clockwork Orange) and Langdon Jones in style and content, for example, but are instead from a new writer. Old ideas in new ways, perhaps. A good start to the issue, if typically depressing. 4 out of 5.

Pauper’s Plot by Robert Holdstock

Pauper’s Plot by Robert Holdstock

A story of a future life in a factory where the protagonist spends his life as a factory slave pauper, wanting to kill his Overseer, Mister Joseph. Effective description of an awful life that is devoted to work – they have no free time, no chance to go outside. There’s an obvious analogy to the factory and the machine our protagonist is slaved to being life’s dreadful grind. Think of it as a Dickensian novel set in the future – rather like the musical film Oliver! I saw the other week, but without the music, which I kept thinking of whilst reading this. Again, not a bad effort, even if the ending is a bit of a let-down. 3 out of 5.

The Pieces of the Game by Gretchen Haapanen

Another story in poetic prose, that style so beloved by Associate Editor James Sallis. The plot, such as it is, tells us of Sarah, living in a smoggy Los Angeles from which she manages to escape the daily drudgery – in other words, similar to Holdstock’s story! The tale is OK but doesn’t really say a lot, other than creating pictures in your head.

But never mind a plot: be in awe of the pretty prose (though occasionally set out in that way of type in various directions across the page that I am starting to really dislike). 4 out of 5.

Black is the Colour by Barry Bowes

Black is the Colour by Barry Bowes

Another story determined to be controversial dealing with the issue of colour. A white man suddenly wakes up one morning to find that he is now black. Deliberately provocative prose – the ghost of Bug Jack Barron hasn’t quite gone away, has it? – but the story makes the point that people of different coloured skin are treated differently in society, and it’s not long before the storyteller’s life suffers as a result. Not a particularly original idea, but it makes its point pretty well. 3 out of 5.

How May I Serve You? by Stephen Dobyns

How May I Serve You? by Stephen Dobyns

A story of consumer capitalist culture, it describes a future world where a man who loves the physicality of coinage goes on a spending spree at Schartz’s, using his own manufactured money. He is arrested and we discover that it is an unfortunate consequence of being reconditioned. A nice take on the influence of money and consumable goods in our lives. I’m surprised that “Coca-Cola” hasn’t had something to say on the story though – or do they see it as subliminal advertising? 3 out of 5.

Crim by Graham Charnock

Crim by Graham Charnock

A story that feels a bit Bug Barron in nature. CRIM is a story of future warfare combined with media saturation. Lots of violent imagery, separate characterisations and made up language. This feels similar to some of the other fiction in this issue and gets across the idea that war is bad in a Brian Aldiss Barefoot in the Head kind of way. The difference here is that CRIM feels like it is trying too hard. 3 out of 5.

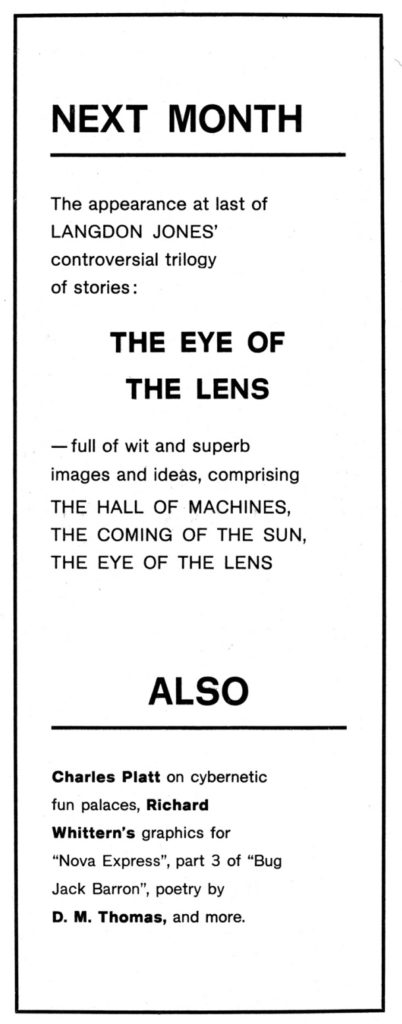

Article: Graphics for Nova Express by Richard Wittern

Article: Graphics for Nova Express by Richard Wittern

Images for what is presumably a new edition of William Burroughs’s Nova Express that seem a bit pointless without context. 2 out of 5.

Sub-Synchronization by Chris Lockesley

Sub-Synchronization by Chris Lockesley

Ah, the inevitable New Worlds sex story! Actually, after that initial attempt of using a discussion of sex to grab your attention, it soon becomes something about time, in that disjointed poetic manner that James Sallis seems to like. I didn’t understand it myself. 2 out of 5.

Baa Baa Blocksheep by M. John Harrison

Baa Baa Blocksheep by M. John Harrison

Another disjointed story about grotesque characters doing something incomprehensible. Like most of the allegorical stories here, it is about impressions and poetic description rather than anything else.

It seems to be about this Arm, who with another person named Block go to work for Holloway Pauce, who for some bizarre reason is experimenting on sheep. Whilst this is going on, we get Ballard-ian extracts of stories that Arm is trying to get published, of characters named Gynt and Morven. Deliberately odd and unsettling, obtuse and simultaneously designed to provoke, it becomes memorable for vivid but fractured sections of prose. For example, the first line is: ”Arm scuttled the streets like a bubonic rat–furtive by nature, flaunting in the exigencies of pain."

Typical New Worlds material. I’m sure it all means something… somewhere, but after two readings, I’m still not sure what that is myself. Appreciate the lyrical imagery; don’t look for meaning. 3 out of 5.

Book Reviews: The Impotence of being Stagg by R. G. Meadley and M. John Harrison

Book Reviews: The Impotence of being Stagg by R. G. Meadley and M. John Harrison

Harrison reviews as well as writes in this issue – I suspect that this will become a regular thing.

Unsurprisingly, the reviewers do not like old-style SF, such as that published by Doubleday, and so give a thumbs-down to Joe Poyser’s Operation Malacca, Lloyd Biggle Jr.’s The Still Small Voice of Trumpets and Flesh by Philip Jose Farmer, although they grudgingly admit that Farmer’s more-sexual tales are more entertaining than the rest. I have tended to think of Farmer as a New Wave writer in the US – Harlan Ellison certainly did in Dangerous Visions, so my surprise is that they have anything bad to say about it at all.

Of the other reviews, R. A. Lafferty’s The Reefs of Earth is regarded as a “slight work… well worth a glance if you have nothing else to read”. The publication of Philip K. Dick’s first novel Solar Lottery shows “how far Dick has progressed in the thirteen years since its first publication, and little else.” Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is “a book for all the family” and will “hardly offend anyone” being seen as “An inoffensive and mundane little piece of Establishment SF.” Lastly, Charles Harness’s third novel, The Ring of Ritornel is seen as “brash, fascinating, eclectic,fast and glossy” but is a less satisfying work when compared with his earlier novels.

Article: Phantom Limbs by Frances Johnston

A medical article that is a little reminiscent of those written by Dr. Christopher Evans back in the early Moorcock issues of New Worlds. It begins with the recent film The Charge of the Light Brigade before going on to discuss the need for artificial replacement limbs and the future of such devices. I guess that it is close to being a robot, but not quite. It’s interesting but feels oddly out of place in this magazine. 3 out of 5.

Summing up the November New Worlds

An issue pleasing in its variety, but rather expectedly more variable in its quality. What we have here is a number of new writers taking inspiration from previously published authors, but as a result we have a lot of techniques we’ve seen before repeated. I recognise Ballard, Aldiss and Langdon Jones in those. The content is more of the usual – strange, disjointed, atmospheric.

I enjoyed most Area Complex, but wasn’t too excited about the Lockesley and the Charnock. The Harrison may be the most bewildering, but Barry Bowes’s story is the one that might cause most outrage, although it isn’t really saying anything new, sadly.

Out of the two issues, I think that the November issue is stronger, simply by having more stories with more of a range, even when a number of them resort to techniques that seem a little familiar. The idea of having an issue with all new writers to this magazine is a good one and shows that there is new talent out there to encourage. The downside of this is that the magazine doesn’t have any big names like Aldiss, Ballard or Disch to encourage the faithful, which might be what the magazine needs to get those reader numbers up, even when some of these new writers seem to be similar in prose, tone and style. Nevertheless, a good issue with good intentions, and one that feels fairly strong, if not entirely successful. It’s a fresh start of sorts, and I look forward to the next issue – hopefully next month!

Until next time – I wish everyone a Happy Halloween.

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

Picture by James Cawthorn

Picture by James Cawthorn

(And where would New Worlds be without a provocative photo or a mention of J. G. Ballard? This is an advertisement on the back cover.)

(And where would New Worlds be without a provocative photo or a mention of J. G. Ballard? This is an advertisement on the back cover.)

![[November 26, 1968] Warhol, Delany, Cornelius and Perversity <i>New Worlds</i>, December 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/new-worlds-december-1968-672x372.jpg)

![[October 22, 1968] Hello Again! <i>New Worlds</i>, October & November 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/NW-October-November1968-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Malcolm Dean

Cover by Malcolm Dean Disturbance of the Peace by Harvey Jacobs

Disturbance of the Peace by Harvey Jacobs

Article: Into the Media Web by Michael Moorcock

Article: Into the Media Web by Michael Moorcock by Malcolm Dean

by Malcolm Dean Biographical Note on Ludwig van Beethoven II by Langdon Jones

Biographical Note on Ludwig van Beethoven II by Langdon Jones And again, something that’s been missing from recent issues, those pictures of strange artwork. This new version has buildings with patterns of light and shadow – and of course, a naked lady. No explanation – I guess we are just meant to be inspired – or aroused. 2 out of 5.

And again, something that’s been missing from recent issues, those pictures of strange artwork. This new version has buildings with patterns of light and shadow – and of course, a naked lady. No explanation – I guess we are just meant to be inspired – or aroused. 2 out of 5. Ah, poetry. 3 out of 5.

Ah, poetry. 3 out of 5.

Cover by Gabi Nasemann

Cover by Gabi Nasemann Area Complex by Brian Vickers

Area Complex by Brian Vickers Pauper’s Plot by Robert Holdstock

Pauper’s Plot by Robert Holdstock

Black is the Colour by Barry Bowes

Black is the Colour by Barry Bowes How May I Serve You? by Stephen Dobyns

How May I Serve You? by Stephen Dobyns Crim by Graham Charnock

Crim by Graham Charnock Article: Graphics for Nova Express by Richard Wittern

Article: Graphics for Nova Express by Richard Wittern Sub-Synchronization by Chris Lockesley

Sub-Synchronization by Chris Lockesley Baa Baa Blocksheep by M. John Harrison

Baa Baa Blocksheep by M. John Harrison Book Reviews: The Impotence of being Stagg by R. G. Meadley and M. John Harrison

Book Reviews: The Impotence of being Stagg by R. G. Meadley and M. John Harrison

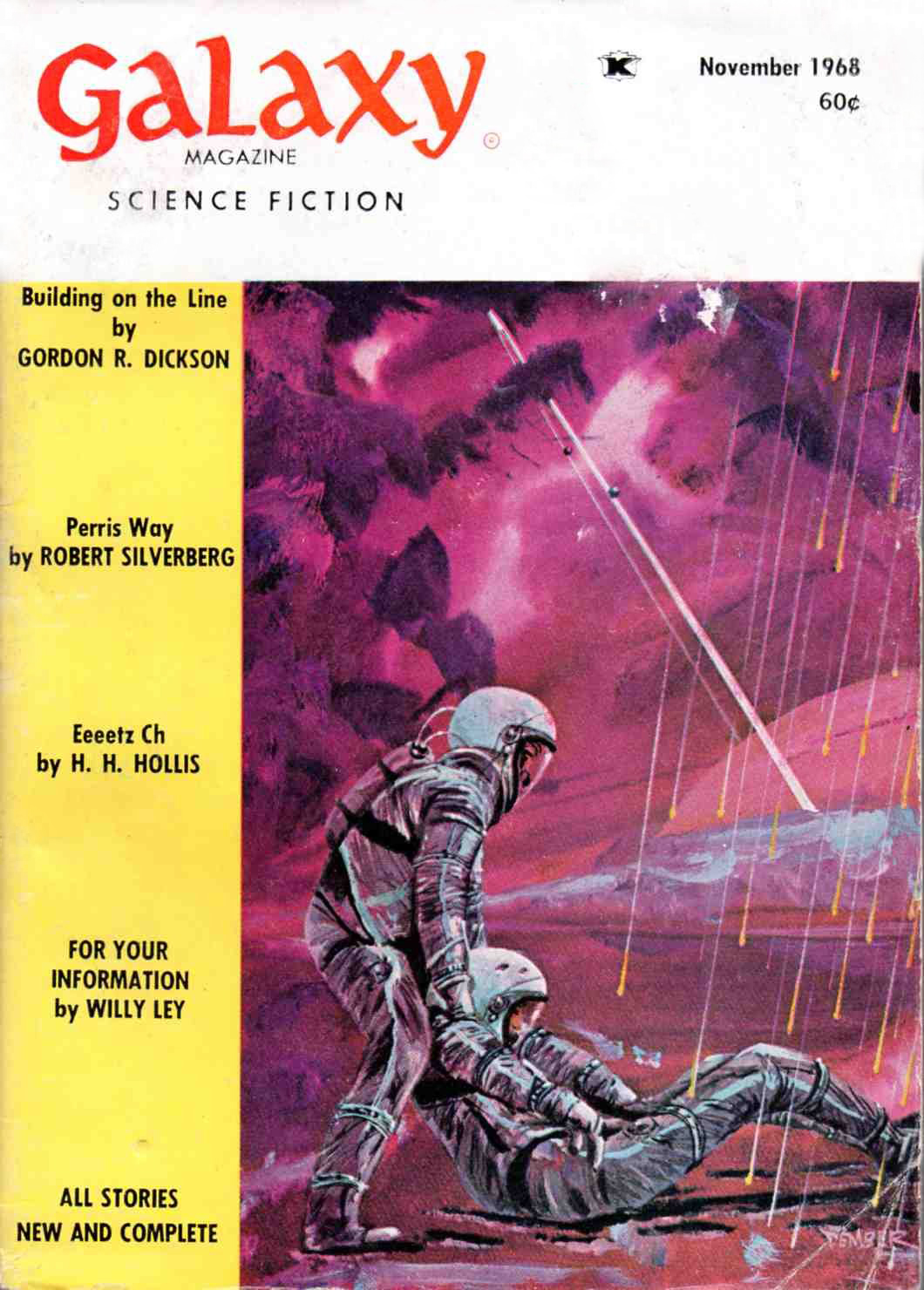

![[October 8, 1968] Probing the future (November 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/681008cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 24, 1968] Reconstructing The Past (<i>The Farthest Reaches</i> & <i>Worlds of Fantasy</i> #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Featured-672x372.png)

![[August 12, 1968] <i>Galaxy's the One</i>? (the September 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/680812cover-1-scaled.jpg)

![[June 16, 1968] More Scandal! <i>New Worlds</i>, July 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/New-Worldsa-July-68-672x372.jpg)

So New Worlds is now part of the records of British government, forever!

So New Worlds is now part of the records of British government, forever! Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

![[June 10, 1968] Froth and Frippery (July 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680610cover-653x372.jpg)

![[April 10, 1968] Things Fall Apart (April 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/amz-0468-cover-447x372.png)

![[January 26, 1968] Jack Barron Returns!<i>New Worlds</i>, February 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/New-Worlds-Feb-68-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch Photos of the key writers this month. New feature.

Photos of the key writers this month. New feature. More sex from Jack Barron. Artist uncredited.

More sex from Jack Barron. Artist uncredited. First page of the article. More cut-up stylings!

First page of the article. More cut-up stylings!

Weird art for a weird story.

Weird art for a weird story.

![[January 16, 1968] Worthy programming (February 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680110cover-672x372.jpg)