by David Levinson

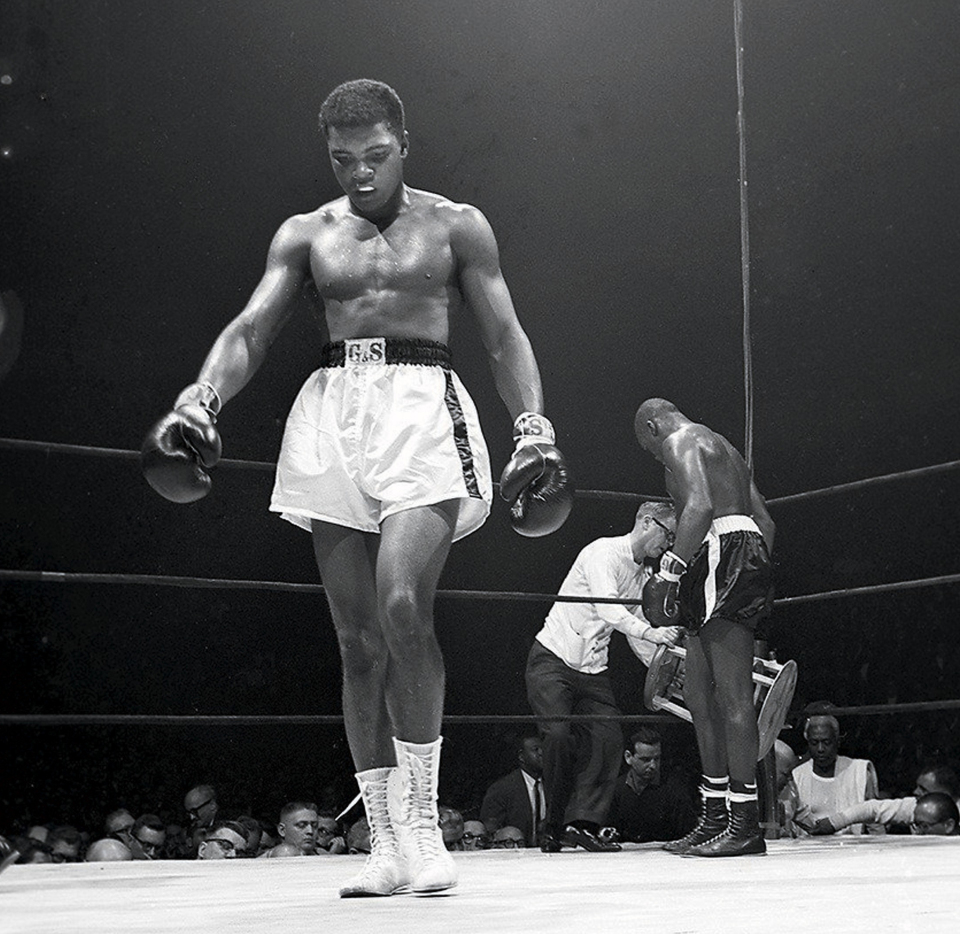

Some people are objectively better at some things than everybody else. Sandy Koufax can pitch a baseball better than almost anybody, and Muhammad Ali is arguably the best boxer we’ve seen in his weight class in a long time.

The problem arises when that excellence in a specialized area leads to an assumption of excellence in other, unrelated areas. I certainly wouldn’t turn to either of the aforementioned men for suggestions on nuclear policy or to bring peace to South-east Asia. Worse still is when whole groups assume superiority over others based solely on an accident of birth.

Heart of Darkness

Last month, I discussed the difficulties faced by the United Kingdom in handing over power to the locals in Rhodesia due to an unwillingness on the part of the white government under Ian Smith and the Rhodesian Front to share power with Black Rhodesians. Alas, the situation has now collapsed completely. On November 5th, the colonial governor declared a state of emergency, blaming Smith and two African nationalist organizations, the Zimbabwe African People’s Union and the Zimbabwe African National Union.

Ian Smith signs the Unilateral Declaration of Independence

On the 11th, the Smith government unilaterally declared independence. Within hours, the United Nations Security Council condemned the action 10-0 with France abstaining. British Prime Minister Harold Wilson has been granted the authority to rule Rhodesia by decree, though what good that might do is hard to see. Wilson steadfastly refuses a military solution and expects economic embargoes to force Smith to capitulate. But with two neighboring nations, South Africa and the Portuguese colony of Mozambique, more than willing to ignore any embargoes, it is likely to be a long time before we see a resolution to this situation.

Conflicts Great and Small

Fittingly, there’s plenty of superiority, assumed and otherwise, in this month’s IF. Let’s get to it.

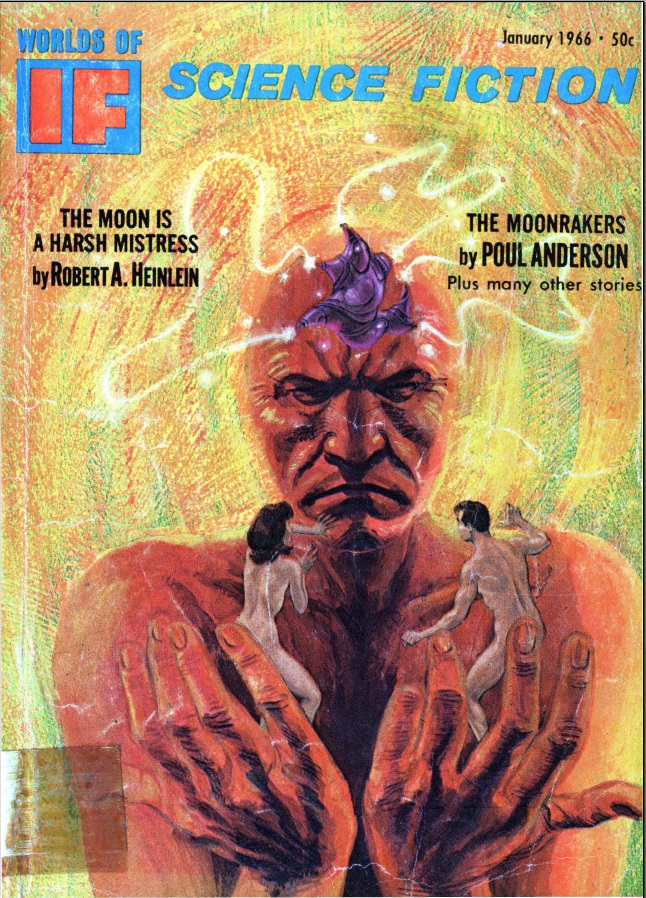

This art for “Cindy-Me” bears absolutely no relation to the story. Art by Morrow

Moonrakers, by Poul Anderson

At some point in the past, a terraformed Mars broke away from Incorporated Earth. The asteroids were colonized from there, and now, while the larger asteroids like Ceres and Pallas remain loyal to Mars, the smaller bodies are seeking their independence. The asterites are pirating Martian shipping to Jupiter with the tacit support of Earth. Because Mars has privatized most government functions, the Interplanetary Shippers’ Association has hired private investigator James Church to solve the piracy problem. His solution proves to be rather unorthodox.

An asterite salvager makes a big score. Art by John Giunta

Initially, I wondered why this story didn’t appear under Anderson’s Winston Sanders by-line, but the differences soon became apparent. Most notably, he seems to pointing out several of the flaws in his noble asterite society in that series. Earth is also somewhat less awful.

Just as a fix-up novel consists of several short pieces cobbled together to make a book, one could argue this is a fix-up novelette cobbled together from several vaguely connected vignettes without the benefit of any connecting material. We jump from incident to incident with few clues as to how we got there or how it all hangs together. This might work better fleshed out to full novel length. On the whole, it’s not objectively terrible, but I expect better from Poul Anderson. Just barely three stars.

Cindy-Me, by Don F. Briggs

Cindy and her twin brother, our unnamed narrator, are on the run from Old Ralph and trying to get to Aunt Ag. They have incredible psychic powers, but even that might not be enough to evade Ralph and his Watchers.

Briggs is this month’s first-time author. I’m not terribly impressed. The pieces don’t really fit together very well, and the tone shifts a few times. Some of that is due to the author’s attempt to play with the reader’s expectations, but he doesn’t quite achieve his aim. The title and references in the story make the twins sound like a gestalt being, but they come off as two individuals. They also grow increasingly unpleasant, which is part of the point, but they’re hard to take. Two stars.

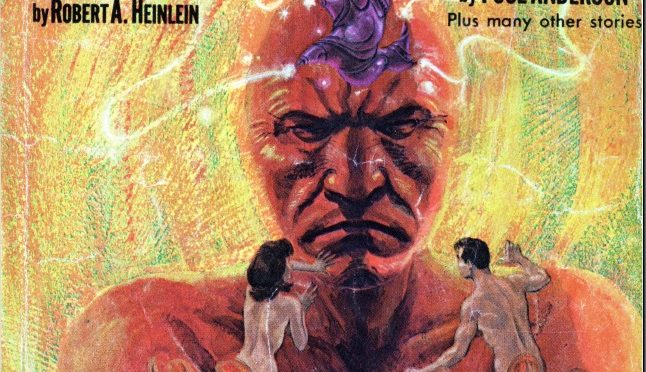

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (Part 2 of 5), by Robert A. Heinlein

Last time around, Heinlein introduced us to the Moon of 2075, a penal colony on the edge of a revolution. At the end of the installment, Mannie, a computer technician, is dragooned into leading said revolution by his tutor, Professor de la Paz, a subversive from Hong Kong Luna named Wyoming Knott, and an intelligent computer nicknamed Mycroft.

Begin Part Two:

Mannie, Wyoh and Prof discuss political philosophy for a while, and then Mike is brought into the conspiracy. He predicts food riots in seven years and cannibalism in less than ten. He also calculates that a rebellion has about a one in seven chance of success and is a bit puzzled when his friends find those odds acceptable. Loonies are gamblers by nature.

What follows is a summary of eleven months of revolutionary organization and planning. Mike creates the persona of Adam Selene to head the revolution. They set up a few fake companies with the purpose of funding the revolution and building a secret electromagnetic cannon, because Mike says they will need to “throw rocks” at Earth. Also of note is the recruitment of eleven-year-old red-head Hazel Meade to oversee the children being used to distribute subversive literature and follow guards. Mannie, Wyoh and Prof start wearing heavy weights, since Mike predicts that at least one of them will need to visit Earth at some point. As the installment ends, Mannie drops in to visit a friend who acts as a judge. This will apparently have a great effect on the course of the revolution.

Our four protagonists. Art by Morrow

There’s not much to say about this one, since it’s just Heinlein setting the final pieces on the board. With any luck, the action will get under way next time. As a standalone, the installment suffers, though it’s actually enjoyable. I’m sure when it’s all together between two covers you won’t even notice.

But that does give me a chance to talk about Mannie’s voice. The Loonie patois is composed of American and Australian vernacular (Mike is a “dinkum thinkum”) and a few Russian loan words along with some Russian grammar, like the lack of definite articles. It works very well and is much easier to read than the Nadsat of A Clockwork Orange. Mannie is one of Heinlein’s best narrators in a long time.

Of final note is young Hazel Meade. I’m pretty sure we’ve met her before. At least, I can think of another Hazel with a family of red-heads and a granddaughter named Meade. She also says her name is on the monument to the revolution back on Luna. Yes, I’m fairly sure this is Grandma Hazel from Heinlein’s The Rolling Stones.

As noted, not much happens, but it has that Heinlein readability. Three stars.

Mr. Jester, by Fred Saberhagen

A severely damaged Berserker has its brain placed in a new ship. This flips a switch installed by the Builders during the testing phase of their destructive creations. A switch that renders the Berserker harmless. Meanwhile on Planet A, which has been cut off from contact with the rest of the human galaxy for a while, a man is accused of making jokes. As punishment, he is sent to an observation post on the edge of the system, where he encounters the harmless Berserker. Together they return to Planet A.

Oh, that’s not creepy at all. Art by Gaughan

This story bears a lot of similarities to Harlan Ellison’s Repent, Harlequin. Indeed, had they come out a year apart, rather than a month, I’d suspect one of inspiring the other. Maybe Fred Pohl suggested the same story seed to both authors. I’ve regularly praised Saberhagen for bringing something fresh to this series every time. The story is still fresh, but for me it doesn’t quite work. It’s not something I can really pin down, but this is the least of the Berserker stories, and I prefer Harlan’s take on the concept. Just barely three stars.

A Planet Like Heaven, by Murray Leinster

On the planet Dorade, the Dorade Corporation harvests kamun logs from a deadly, mobile tree using animal workers. As usual, the Home Office sends new instructions with the regular ship and only delivers them just before departure to keep the local managers from objecting. Headquarters is demanding a doubling of production and has instructions on how to achieve this. Orders which appall local manager Chalmers and head overseer of the workers Burke. Neither man feels he can defy orders, since that would mean quitting and then they’d have to pay for their passage back home, which would bankrupt them. The next ship brings no less than the president of the corporation, who takes charge of the operation, disgusted by the local men’s failures.

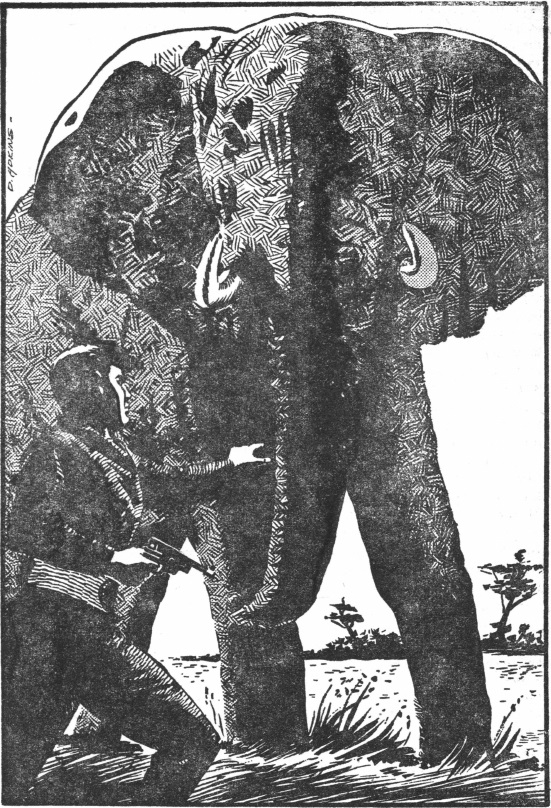

Chalmers and one of his best workers. Art by Adkins

Murray Leinster has been off his game lately. Here, he returns to form at long last. This is a good story that makes its point clearly and reasonably consicely. Alas, while it’s obvious from the text, it’s never explicitly stated until the final line that the workers are elephants. The illustration gives that away and detracts somewhat from the punch of the ending. A pity, but still a solid three stars.

The Smallness Beyond Thought, by Robert Moore Williams

Two scouts are hiking a desert canyon, collecting rocks. Finding an interesting piece of quartz, they pull out an odd device to test it. After this, we are given the history of the strange hermit who has lived here for decades beyond memory and built a number of strange structures and walkways that go nowhere. He also seems to be friends with the local rattlesnakes. Finally, we meet Ed Quimby, the number two man at the nearby observatory, who befriends the hermit after a fashion, and unwittingly gets involved when an outsider seems to be after the hermit.

Someone approaches the smallness beyond thought. Art by Gaughan

Williams presents us with a number of mysteries and resolves none of them. We learn nothing about the hermit, the (possibly two groups of) people after him or why they want him. We do learn the function of the odd structures, but nothing of their purpose. On top of that, the hermit has an incredibly annoying accent. And this all goes on and on for over thirty pages, leaving us none the wiser as to what has happened. A very low two stars.

Summing Up

Well, the stories this month are certainly full of people exerting an assumed superiority over others, from government goons to corporate heavyweights. And just like in real life, they’re frequently very wrong. Unfortunately, this time out the stories produced aren’t all that great. Let’s put this one in the books and hope for better efforts (and some actual action from Heinlein) next month.

At least it doesn’t seem to be a Gree story.

I had slightly different feelings on the magazine from yourself. But before I get to the stories, what is with the union bashing introduction from Pohl. Also seems to show a distinct lack of understanding of modern labor relations and the reason for contemporary strikes. Is he trying the emulate Campbell and get in some of that sweet reactionary money?

The Moonrakers didn't really work for me, I think it being so fragmented meant it never felt like a good overall whole.

Cindy-Me, on the other hand, I liked slightly better. This reminded me of the kind of vignette you could see in New Worlds (and of the recent Out of the Unknown episode, Stranger in the Family). Not amazing but a nice change of pace for a magazine that is usually so backwards facing.

I liked this part of The Moon is the Harsh Mistress more than the last actually. A good build up of the revolution, character work and long term tactics. Actually reminded me a bit of some of the Foundation stories. If it wasn't for Heinleins comments about women I would thinking this was heading for five stars.

Mr. Jester definitely is reminiscient of Repent Harlequin, so something is clearly in the air. Moorcock has also published a novel around this idea called The Fireclown, and I would also argue Of Goodlike Power has shades of this. Either that or all four authors met in the WorldCon bar and came up with the idea? Either way this is the weakest of the treatments I have seen.

A Planet Like Heaven also felt like a weak treatment of a very common idea. I am still not convinced Leinster has evolved since the early 1950s.

Talking of old hands, Robert Moore Williams I enjoyed back in the 40s but he always feels like he struggle do anything more than pulpy. That is evidenced here.

"I liked this part of The Moon is the Harsh Mistress more than the last actually. A good build up of the revolution, character work and long term tactics. Actually reminded me a bit of some of the Foundation stories. If it wasn’t for Heinleins comments about women I would thinking this was heading for five stars."

Manny's comments about women are annoying, but they are not necessarily Heinlein's.

The biggest one that gave me pause was talking about Loonies..and women, as if women are not Loonies.

Again, Manny's got his own perspective. At least Heinlein gave us Mim and Wyoh and Hazel.

Whilst that is a fair point, with some of the things Heinlein has written in the past, such as the rape comments in Stranger in a Strange Land or the literal shotgun wedding in Let There Be Light, and his tendency to make main characters his mouthpiece, I am less inclined to give him the benefit of the doubt. But that is a fair response and maybe we will see more to counterbalance it in future parts of this story.

He has certainly turned a corner in terms of knowing not to just have his characters proclaim his political philosophy in long dull speeches. Maybe he has improved in this area as well.

We haven't seen (much) nudity or cats yet, though de la Paz effuses strongly for Libertarianism.

I guess the title of "The Moonrakers" refers to the old story about the smugglers who evaded the authorities by pretending to be raking the water for the moon. Maybe this is related to the con game played at the end? Anyway, I thought the story took a long time getting to that. Interesting background, but wandered all over the place.

"Cindy-Me" was intriguing, if somewhat confusing. Definitely on the dark side, though.

"Mr. Jester" was pretty good, even if it did wind down towards the end. I'm impressed that the author can write such wildly different stories about the Berserkers.

"A Planet Like Heaven" seemed to be mostly a plea for people to treat elephants (and other animals, I presume) decently. Even without the illustrations, it was clear that they were elephants (or at least elephant-like) very quickly; their trunks, etc. I don't know why the word was avoided until the end.

"The Smallness Beyond Thought" just baffled me. I never did figure out exactly what was going on.