by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

After all the excitement about the Worldcon in London at the end of last month (I gather a good time was had by all!) we are back to normal this month.

The issue that arrived first in the post this month was Science Fantasy.

The cover by Agosta Morol hearkens back to mythology, as did the cover of the September-October 1964 issue. It’s clearly deliberate as the main story then, as now, was by Thomas Burnett Swann, who is by now developing quite a reputation for revisiting ancient myths and revising them for a modern-day readership.

After last month’s Guest Editorial by Brian Aldiss, this month the Editorial this month is by Kyril’s second-in-command. It rather makes me wonder what has happened to Mr. Bonfiglioni, although the top of the editorial states that he is away in Venice, stargazing – lucky thing!

Having said that, the Editorial is not that different to normal. Mr. James Parkhill-Rathbone begins in a roundabout way by talking of architecture and design before going on to make the point that because humans have a lack of logic then future trends are nearly impossible to predict accurately. I liked it – there’s an entertaining mix of anecdotal humour and serious point-age going on.

To the actual stories.

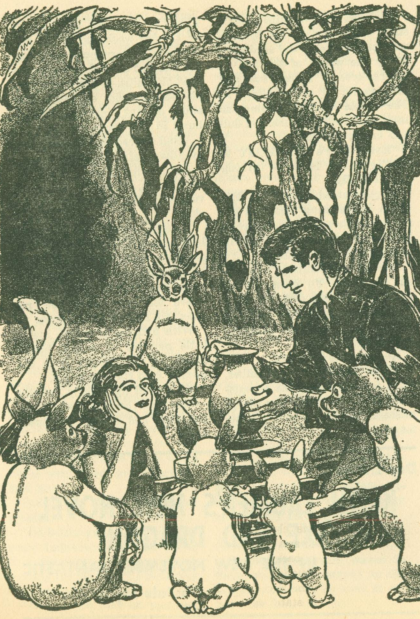

The Weirwoods (Part 1 of 2), by Thomas Burnett Swann

And so straight in with a bang. If you have been following my writings here, you may know that I really like Burnett-Swann’s re-imaginings of ancient myths and folklore. His story The Blue Monkeys was the first issue of Science Fantasy I reviewed here way back in September 1964, and since then his material has always entertained. So, having tackled Greek myths and Persian myths, this time he is telling a tale from Etruria. It is the story of two cultures – one human, the other mythological – and the difficult relationship the two groups have with each other. At the beginning there is a reluctant trade between the Etruscan people of the city of Sutrium and the many different species of the neighbouring Weirwood, where we have Centaurs, Sprites, Nymphs, Fauns and the like.

The main characters are Lars Velcha of Spina and his daughter Tanaquil. Whilst moving to Sutrium they stop at a lake, and Lars captures a young teenage Water Sprite called Vel to make him a slave for Tanaquil. When travelling troubadour Arnth visits Sutrium and is invited to stay at their house, he decides to free Vel and return him to his people of the lake. This involves Arnth going to the lake and negotiating with Vegoia, who is the sorceress of the Weir people. They return to Sutrium and end the story on a cliffhanger to be concluded in the second part next month.

Once again Burnett Swann entices with his expressive descriptions and context. His writing clearly shows an intelligent understanding of ancient myths. In this mystical land before the Romans he manages to eloquently and lyrically describe the different cultures. The Weir folk are appropriately unearthly, whilst the humans seem to reflect both the innocence and the avarice of human nature.

Although parts do read like a fairytale, it is definitely a story for adults. Whilst Thomas’s previous stories have always had an element of sexuality to them, The Weirwoods is perhaps the most explicit yet. There’s sex and a lot of nakedness and men in loincloths which may be too frank or even shocking to some readers – most of the men-slaves and the male creatures are naked, for example, and the author spends some time giving details of this. He doesn’t hold back too much on the youthful desire the virginal Tanaquil has for Vel and Arnth, either, or indeed the relationship of Arnth and the weir woman Vegoia. There’s also explicit scenes in the entertaining stories Vel tells his audience as part of his performances. Such aspects lend a certain degree of maturity to the story that, whilst not for everyone, add depth and detail.

It is a sign of confidence that the serial fills over 70 pages of the magazine’s 130 this month. As ever, literate and entertaining without being obtuse. 4 out of 5.

Ragtime, by Pamela Adams

A new name to me, and – good heavens! – a woman writer! (Actually, I think that both magazines have tried hard to include women writers in the last couple of years, although there is a noticeable dearth generally.) The story is really a ghost story told by a woman about the disappearance of her husband one night whilst staying on a river boat. There’s some “Be warned – I should tell you about the weird goings-on…” type of comments, but it is readable, if a tad predictable. 3 out of 5.

Green Goblins Yet, by W Price

Another new name. This month’s lightest tale is one of those jokey-style shaggy dog stories set in a diner, where a mysterious stranger immediately nicknamed ‘Egghead’ comes looking for a goblin after a newspaper story of sheep being savaged in the Kinder Scout area. After asking the locals in the diner for advice, Jigsy and Spike agree to help find it – which they do. A story in that category I normally think of that starts, “You’ll never believe it, but…” Entertaining enough. 3 out of 5.

State of Mind, by E. C. Tubb

The popular return of one of the old guard, E.C.’s story is about a man who begins to suspect that his wife, who he has been married to for more than fifteen years, is not who he thought she is. Is it the sign of a mental breakdown, or something more sinister? It is well told, but a lesser tale of paranoia and perception, one that slow-burns until the violent end. One for the Twilight Zone fans, I guess. (We still haven’t seen the television series here in Britain, by the way.) 3 out of 5.

The Foreigner, by Johnny Byrne

I said last month that Johnny has produced some very strange stories in the past, with varying degrees of success for me. This is another oddity, a story told by a man meeting his seemingly-eccentric new neighbour, who insists on trying to throw himself out of his window wrapped in a mattress plugged into the mains electricity. The reason for this is typical Byrne material, but I quite liked it. 3 out of 5.

Goodnight, Sweet Prince, by Philip Wordley

Philip last appeared in the May 1965 issue of Science Fantasy with Timmy and the Angel. This time his story (quoting Hamlet, literary fans!) is of a future where people can time-travel into the past. On this particular occasion film magnate Art Kirbitz and his crew have travelled to Shakespearean England to film an original version of Hamlet. Director Harry Gorrin goes in search of the original manuscript in Shakespeare’s own writing, but finds a letter being written by the Bard that puts a very different slant on the man. The twist in the tale at the end is nothing really new, but I quite liked this one, although the modern-day patois between the financier and his modern crew, full of “beefy cats” and “gonnas”, is a little too unsubtle for my liking. However, this is the best story I’ve read from Philip. 3 out of 5.

Summing up Science Fantasy

Any issue that has Thomas Burnett Swann makes me happy – entertaining storytelling giving us a glimpse into a different world. I’m pleased that this one doesn’t let me down and I’m already looking forward to next month’s continuation. The rest of the issue is a little more variable but, in the end, rather pedestrian. Not really a bad story there, but generally too bland for me. Overall then, a rather middling issue, dominated by the raunchy Burnett Swann.

Onto this month’s New Worlds.

The Second Issue At Hand

After the Aldiss issue last month, we’re almost back to normal with this month’s arrival of New Worlds. This includes a dreadful uncredited cover.

This month’s editorial from Mike Moorcock is short and rather perfunctory. He points out that the stories this month are “closer to the imaginative fantasies of Kafka, Peake or Borges than, say, the work of Asimov or Heinlein” before then reviewing an issue of one of the semi-professional magazines and finally making the point that emotion is as important in sf as much as conceptual ideas. It feels like a mixed hodge-podge of ideas without too much thought.

To the stories!

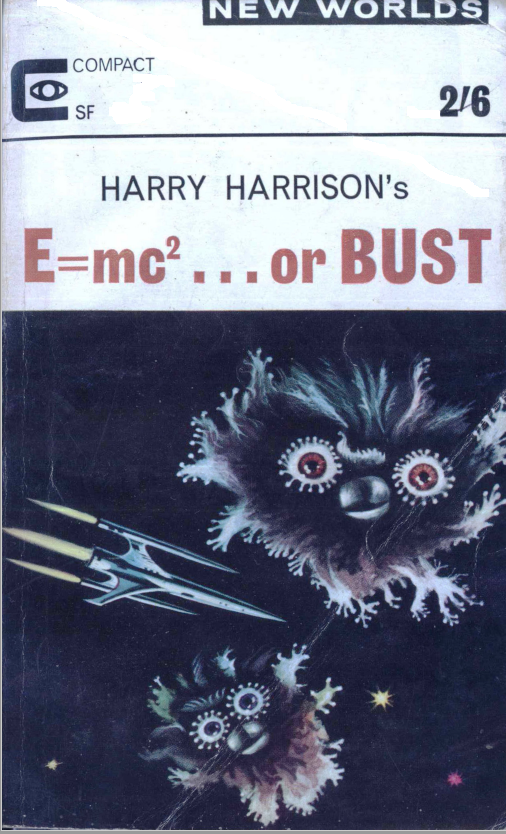

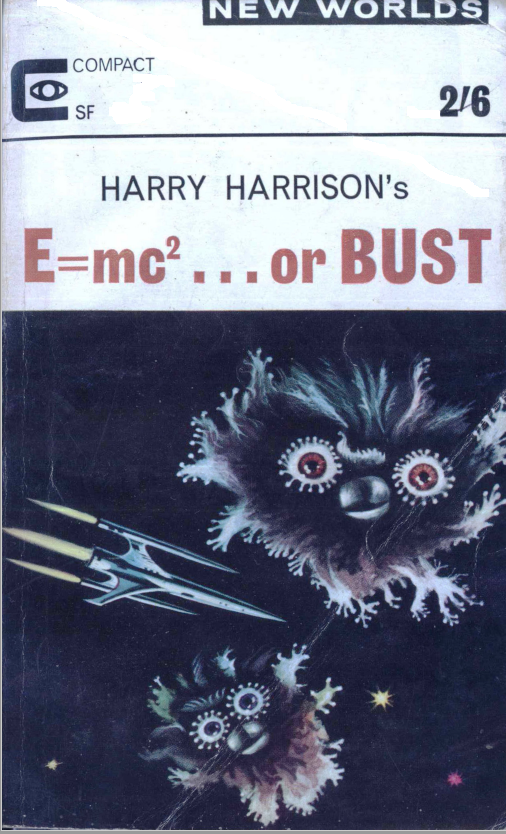

Bill, the Galactic Hero, Part 3: E=mc2 – OR BUST, by Harry Harrison

Straight into the final part of Harry Harrison’s parodic serial, where hapless Bill finds himself in court for desertion. He is placed in prison to do hard labour for one year and then sent back to the battlefront on a reduced rank. The place Bill goes to reminded me of Harrison’s other recent novel, Deathworld, as it is a deadly planet, and the story seems much more serious at this point. He meets old friends and enemies there. The end of the story turns full circle.

I really want to like this story, and I know many that do, but despite trying I just can’t warm to it. This one seems to totally run out of steam. In addition, the creation of a character that is an “Arabic-Jewish-Irish con man” seems to be wanting to offend as many people as possible. Others however find it hilarious. 3 out of 5.

The Golden Barge, by William Barclay

The first of Moorcock’s vaunted allegorical stories. (William Barclay is actually Michael Moorcock in another of his guises.) Jephraim Tallow finds himself chasing a golden barge down a river. His boat runs aground on a sandbar. Floundering onto land, he meets Pandora, a strange woman with green eyes, who takes him home. She seduces him and he falls in love with her. However, this idyll is interrupted when a group of drunken revellers turn up. After some sort of orgy, Tallow realises that he must continue his journey on the river, but to do so means leaving Pandora. Pleading by Pandora to stay leads to a sad end.

I get that the story is really a tale of a man’s life-journey and how he must continue to travel through life, despite the distractions that come his way. At times, the story is quite lyrical, but otherwise it didn’t really do much for me. I suspect that some of the allegory is beyond me. 3 out of 5.

Heat of the Moment, by R. M. Bennett

Nuts-and-bolts salesman Chris Parker finds himself rescued out of a burning building to be abducted by Collectors of the Prime Government of the Second Planet of Rigel as a sample of the fauna of Sol Three. Despite the good intentions of the aliens, the situation doesn’t end well. A one-trick tale that seems fairly pointless. 3 out of 5.

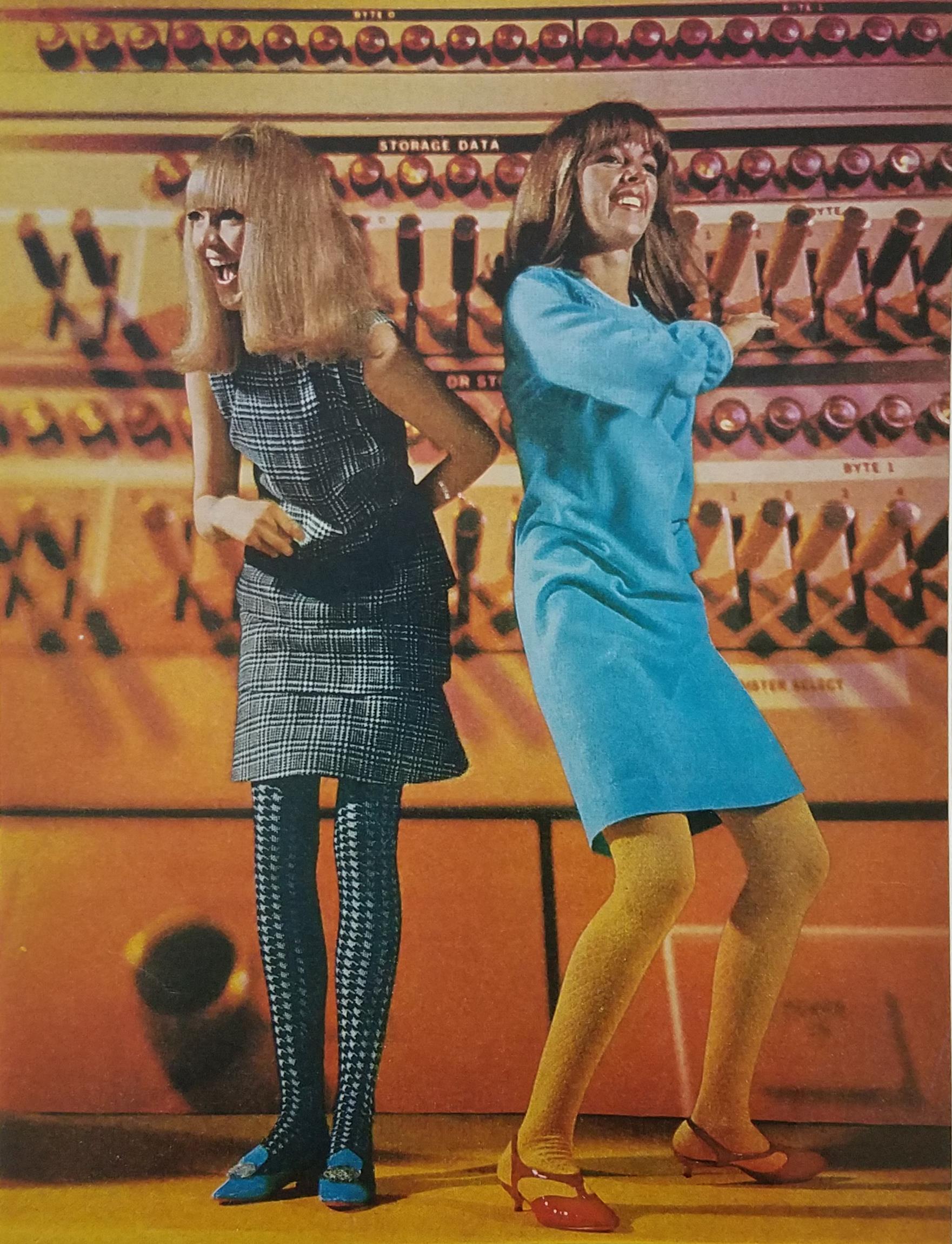

Emancipation, by Daphne Castell

For the second time in two months we have that rare event of a story written by a woman. It is something that we should see more of in these magazines and Ms Castell takes her opportunity well. Emancipation initially reads like an old-style fantasy tale with seemingly primitive alien lizard-men keeping the seemingly less intelligent women of the tribe penned up and looked after as if they were animals.

With names like “Krug of Stok”, at first I thought that this was a parody of the Robert E Howard Conan stories, although we later discover that the Stokka are a seemingly primitive race living on the planet Stok. When Krug hears from Skag and Lopp, Lopp tells them of the technological gifts that space-faring Terrans from Sunward 3 bring to newly discovered planets. The Stokka men realise that in return for the setting-up of a space beacon and a Galactic Embassy they could gain technological power, wealth and status on their rather run-down planet. The aliens decide it would be a good idea to fete the humans, despite their cultural differences, and to show willingness re-educate some of the Stok women into the ways of the Terrans. This leads to cultural change previously unimagined by the men.

Another ‘comedy’ story, this time a comedy of manners and different cultures, based around the idea that how people see different cultures is funny. It’s really one of those old adventure stories where explorers act as missionaries to primitive tribes, but in a science fictional setting.

In the end, the story was better than I thought it was going to be – as comedy I enjoyed it more than Bill’s story, for example – but not a memorable one. 3 out of 5.

Jake in the Forest, by David Harvey

This story describes a series of lifecycles. Firstly, Jake travels through a forest, marvelling at the complex ways in which patterns and processes are present. Like in the Golden Barge, he meets a woman who feeds him and puts him to bed, after which he appears to be back in the forest in a different form. Approaching a megalith, he appears to be buried by it but instead takes another form, appears in a cavern by a lake and then the sea. Finally, he appears to be in bed in a forest cottage, gets up, washes, eats and drinks, and meets a beautiful woman. It appears that this cycle keeps him eternal.

Another allegorical story, quoting Ibsen but little more than a series of expressive set pieces. Poetic in its descriptions, but it did little for me. Seems to want to be Ballard. Despite Moorcock’s attempt in the Editorial to explain its purpose here in the issue – it is written “from a creative need to find fresh methods of telling a story and making a point” – it gives lots of description but the point is weak, not to mention unintelligible. Not for me. 2 out of 5.

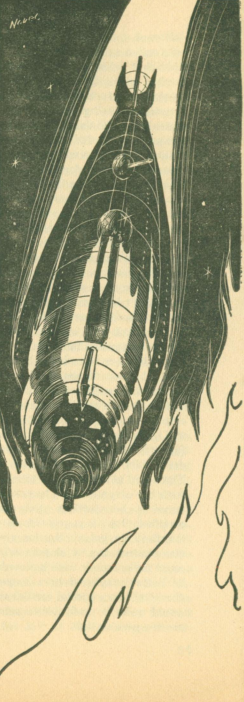

… And Isles Where Good Men Lie, by Bob Shaw

Illustration by James Cawthorn

The return of Bob Shaw after a long absence from this magazine is a good thing, although at first glance this one reads like a traditional sf space opera story. Lt. Col. John Fortune is commander of a military base at United Nations Planetary Defence Unit N186. Nesster spaceship Number 1753 looks like it is due to land at his base, and the unit is put on alert. The legendary ‘Captain Johnny’ is put on display to the press as a sign that all is well, as a hero of the Nesster War.

However, despite all of the surface sheen and bluster, behind the scenes the story is less rosy. Fortune’s friend and scientific genius, Bill Geisler, is asked by Fortune to try and find the guiding spaceship and shoot it down before it lands.

More so, Fortune’s personal life is falling apart. His wife, Christine, is clearly having an affair with charismatic youngster Pavel Efimov, something they barely seem to hide. The plot edges into a soap opera melodrama, rather than a space opera.

Nevertheless, all is resolved at the end.

An odd one this, in that Bob has taken a somewhat traditional sf plot and given it some modern, if unusual touches. Fortune is overweight and yet a figurehead hero, with a domestic life that is about as far from the American ideal as you’d expect. I liked the fact that it was set in Iceland, again somewhere different from the typical US missile base. There’s also some debate about what to do with the aliens, once seen as a threat and now possibly something more. On the downside though, at times the story can come across as a tale of macho-posturing which at times veers into near- hysteria. It’s good to see Bob back, but this is not one of his best. 3 out of 5.

Book Reviews and Dr Peristyle

In the review section, amusingly titled Self-Conscious Sex, only one book is reviewed this month. Charles Platt reviews Robert A Heinlein’s A Stranger in a Strange Land as “a remarkably dull book”, where “Stylistically, cloying American cliché and banter merge with a coyness…inconsistent with the self-consciously bold aim to be frank about sex…” Clearly not a fan.

In happier news, “Dr. Peristyle” (aka Brian Aldiss) is back. This month he holds forth on topics as wide-ranging as religion, the function of sf as ‘literature’, the importance of scientific accuracy and whether publishers are producing quantity rather than quality. It continues to make me laugh.

Summing up New Worlds

An issue with lofty ambitions but for me surprisingly mundane. The allegorical tone of some of the material is a worthy attempt to be different, but left me unimpressed. And whilst many readers will be sad to see Bill the Galactic Hero go, (see the ratings for the first part in issue 153 below), I won’t. Here’s to a fresh restart next issue.

Summing up overall

Although neither issue is an outstanding one, as you might gather, it is pretty clear which issue I enjoyed most this month. I appreciate what Moorcock is trying to do in New Worlds, but for me the more memorable read is Science Fantasy by far.

Until the next…

![[October 18, 1965] Turn, Turn, Turn (November 1965 <i>Fantasy & Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/651018cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1965] Gimmickry (November 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/1965-11-IF-cover-645x372.jpg)

![[September 30, 1965] Big and Little Bangs (October 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650930cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 26, 1965] Allegory and Mythology <i>Science Fantasy</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, October 1965](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/sf-nw-october-1965-672x372.png)

![[September 20, 1965] Unfinished Business (October <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650920cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 16, 1965] Blessed Are The Peacemakers (November 1965 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Worlds_of_Tomorrow_v03n04_1965-11_0000-2-395x372.jpg)

![[September 14, 1965] The Face is Familiar (October 1965 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/650914cover-551x372.jpg)

![[September 12, 1965] So Far . . . Well, Fair (October 1965 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/amz1065-cover-497x372.png)

![[September 6, 1965] War and Peace (October 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/IF-1965-10-cover-657x372.jpg)

![[August 26, 1965] Stag Party (September 1965 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/650828cover-396x372.jpg)