by Fiona Moore

I have been spending a lot of time lately at the Institut Français, both for their interesting lectures and films, and because they have a comfortable reading room which is handy for the universities and museums. This means I have been perusing more than a few copies of the comic magazine Pilote when I’m in town for a lecture.

While Pilote, edited by René Goscinny of Asterix fame, has an excellent variety of styles and artists from Francophone Europe, it’s very rare for it to venture into science fiction.

However, this seems to be changing, with the introduction late last year of a new series, written by Pierre Christin and drawn by Jean-Claude Mézières: Valérian, Agent Spatio-Temporel. Although possibly it ought to be called Valérian et Laureline, for reasons I’ll explain below. So far we’ve had one complete story and one nearly-completed: Les Mauvais Rêves (Bad Dreams) serialised from 9 November 1967 to 15 February 1968, and La Cité des Eaux Mouvants (The City of the Shifting Waters), which began on 25 July this year and is clearly moving towards a climax.

Les Mauvais Rêves is more loosely sketched, in all senses of the word, than its sequel. The story takes place in the year 2720, when the instantaneous teleportation of matter through time and space has been achieved. The result is that that the inhabitants of Galaxity, the planet-spanning empire, have no need to work, except for a small cadre of bureaucrats and agents who are mostly charged with protecting society from time-traveling pirates and scouting for new resources on distant worlds. Everyone else entertains themselves through dreaming.

When people start having nightmares, it transpires that the former head of the dream service, Xombul, has sabotaged the dream computers and fled to medieval France in the year 1000. Agent Valérian pursues him there, where he finds that Xombul is disgusted by humanity’s softness and addiction to dreams. Having learned a set of spells from a medieval magician that will turn humans into monsters and make them follow him blindly (this is, shall we say, not a historically accurate representation of eleventh-century France), Xombul plans to return to the future and take over as emperor of Galaxity. With the aid of a local young woman, Laureline, Valérian must thwart his plans.

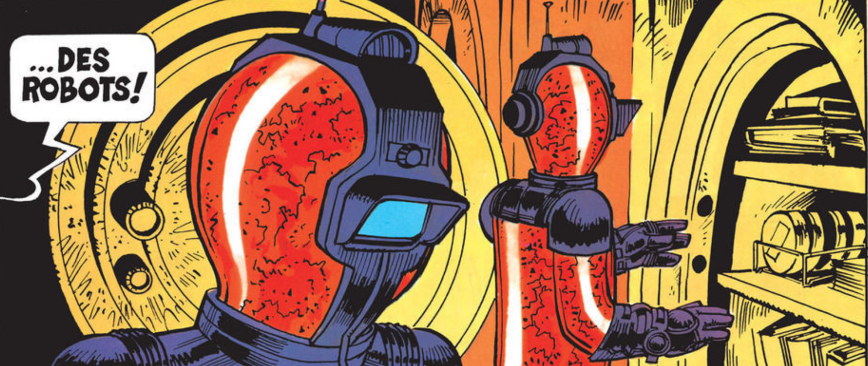

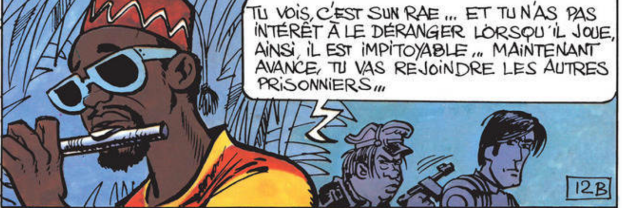

In the second story, Xombul escapes from custody and flees again into the past, but this time, more cleverly, he has gone into the “Forbidden Zone” of 1986. We learn that the explosion of a hydrogen bomb in that year led to a four-century-long dark age on Earth, which the spatio-temporal agents are not supposed to visit. Valérian and Laureline, the latter of whom has now become a fully-fledged space-time agent, pursue him, of course, to a flooded mid-Eighties New York ruled by looter gang leader and free jazz enthusiast Sun Rae, but what Xombul is doing with his army of robots in the former UN headquarters remains a mystery so far.

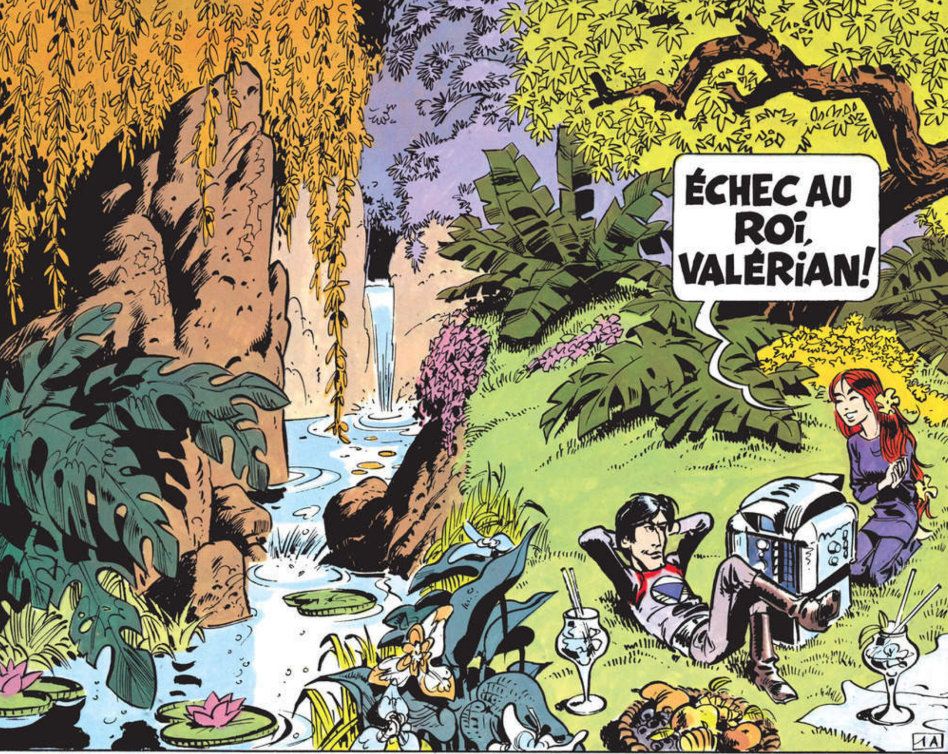

The series as it currently stands shows a lot of promise. Unusually for a European comic, Galaxity is populated by people of all ethnicities who are represented without caricaturing or stereotypes: the same is also true of 1986 New York. There’s an explicit nod to the emerging sub-genre of African and African-American SF and fantasy in the character of Sun Rae, who is based on jazz musician and SF creator Sun Ra. He is portrayed as a shrewd political leader, who is possibly the only one in New York to have realised that the most valuable thing in the city is not the jewels and precious metals, but information and scientific knowledge.

The treatment of women is also exceptional: while there are only two women with speaking roles in the story, and while Laureline does tend to wear figure-hugging costumes, she is never a passive or helpless victim, and so far she has rescued Valérian from danger more times than he has rescued her. The relationship between the two, while affectionate, is also clearly professional, hence why I suggested that they might be regarded as co-protagonists rather than the male agent taking the most prominent position.

There are also some interesting hints at the way in which the story might develop. Galaxity is plainly not the utopia it claims to be, if most of the population are simply dreaming their lives away: totalitarian though Xombul is, one can see why he finds it so frustrating. It also appears to be governed by small, petty bureaucrats with whom it’s difficult to sympathise. We have not seen any aliens so far, and one wonders if this is a universe with only humans, or if their absence hints at something darker. I’m not quite sure what to make of the apparently unproblematic existence of magic in the story, where medieval France is apparently full of wizards and monsters: whether it’s a confusing mixture of genres or a clever, New Wave, challenging of what we interpret as science.

The story also has a pleasing wit, for instance a rather delightful sequence in La Cité des Eaux Mouvants where Laureline explains how she got from Brasilia, where she arrived in the past, to New York, where her lighthearted narrative of borrowing a plane from the President and hiding it in the suburbs, is belied by the cartoon panels showing her stealing the craft and crashing it into a barn.

So far, the most problematic aspect is the variable character art. While Mézières’ landscapes and cityscapes are beautifully rendered, whether a luxury pleasure-garden on Venus or an apocalyptic New York bleakly studded with advertisements, the characters are strange, often grotesque, and change shape from panel to panel. Sun Rae, for instance, gains a bewildering amount of weight between his first and second appearance in the comic. The writing, also, seems on firmer footing in the second story than the first, with Les Mauvaises Rêves involving a lot of plot conveniences and contrivances.

Despite this, I certainly plan to keep following the series, and I hope an English translation will soon be forthcoming, to bring it to a wider international audience. Comics aren’t just for kids, and Valérian shows how the graphic medium can be used to build a sprawling spatio-temporal SF epic.

Four stars.

![[September 12, 1968] I’ll See You In My Dreams: Valérian, Agent Spatio-Temporel](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Screen-Shot-2023-09-04-at-13.23.11-672x366.png)