by Kaye Dee

I’m so excited at the moment because, after several cancelled launch attempts, the first test flight of the Blue Streak rocket went off successfully yesterday (June 5) — it makes me wish I was back at the Weapons Research Establishment right now working on the trials computing! This is the first time such a large rocket has been launched at Woomera. The Blue Streak is just on 70ft tall and 10 ft in diameter, so it made quite a sight sitting on the launchpad at the edge of Lake Hart, which is a salt- lake that only occasionally gets filled with water. I went out there a few times when I visited Woomera and the contrast between the red earth, the deep blue sky and the white salt-lake is quite striking.

The Blue Streak rocket has something of a chequered history. When it started development in 1955 as a long-range ballistic missile for Britain’s nuclear deterrent, I don’t think anyone imagined it becoming a satellite launcher. The idea then was to fire it at targets in Eastern Europe or the USSR from either Britain or British-held territory in the Middle East. In fact, the Blue Streak design was based on the American Atlas missile, although Rolls Royce developed its new RZ-2 LOX/Kerosene engines for the British version.

When the Commonwealth Government agreed in 1956 to allow Blue Streak to be tested in Australia, it led to a huge development programme to open up the full length of Woomera Range for use, because the trial flights were planned to cover well over one thousand miles, travelling north-west from Lake Hart almost to the Indian Ocean! From Lake Hart, tracking, measuring and recording instruments had to be installed across the deserts of central Australia all the way to the Talgarno impact area in Western Australia. They even built a small town at Talgarno to house the researchers who would examine each missile when it impacted at the end of its test flight. Mr. Len Beadell, who is a real character and an incredible bush surveyor (he actually surveyed the area for the Woomera Range when it was first established), put together a road building team and they have graded hundreds of miles of new roads through the outback, along the length of the downrange to Talgarno.

So it was a big shock to us here in Australia when Britain decided that Blue Streak was already obsolete as a weapon and cancelled the programme in April 1960, without any real consultation with the Australian Government. As you can imagine, this caused a major outcry here and in the UK and there was a lot of political embarrassment all round.

But as early as 1957 I was reading articles in British aerospace magazines about the possibility of turning Blue Streak into the first stage of a satellite launch vehicle using a Black Knight, which is a large British sounding rocket used for defence research at Woomera, as the upper stage. This sounded like a great way for Britain to develop its own launch capability, but the UK Government wasn’t interested until it started looking for a way to recoup some of the enormous investment in Blue Streak after they cancelled it as a missile. The initial idea was for a Commonwealth satellite launcher to be developed and used by Britain and other Commonwealth nations. However, New Zealand was the only Commonwealth country that expressed any interest in that project — even the Government here didn’t show any interest, which really surprised me given how much work we do with sounding rockets at Woomera and space tracking for NASA. Anyway, with so little interest that idea went nowhere.

However, Britain wasn’t giving up on the satellite launcher idea and started to canvass European nations for their interest in developing a European launch vehicle so that they would not have to rely on the Americans to launch satellites for them. Of course, the British probably also thought that this project might help to smooth its way into the European Economic Community, which they are very keen on joining. By 1962, France, Belgium, West Germany, Italy and the Netherlands all agreed to participate in the rocket project. This has led to the formation of the European Launcher Development Organisation, which we call ELDO. Because of the complexity of the international negotiations needed to ratify its charter, ELDO didn’t formally come into existence until 29 February this year, but work has been going on since 1962.

Under its charter, ELDO is going to develop an independent, non-military European satellite carrier rocket, to be called Europa. The Blue Streak will be the first stage of the rocket. France will provide the second stage, which is going to be called Coralie (and I’m told that’s partly because Coralie rhymed with Australie, the French word for Australia). West Germany is going to produce the third stage: I think is going to be called Astris. The test satellite that will be launched by the Europa is being developed under the leadership of Italy, while The Netherlands and Belgium will be responsible for the development of telemetry and guidance systems. So all the countries in ELDO will have a part to play in the programme.

Australia’s part will be to provide the launch site for the Europa rockets. Since the Blue Streak is the first stage, it makes sense to use the launchpad and other facilities already built at Woomera for ELDO’s launch operations. This makes us the only non-European member of ELDO. In fact, the Commonwealth Government has insisted that Australia be considered a full, but non-paying, member of ELDO, contributing the Woomera facilities and their operation in lieu of the financial commitment that the other member states are making.

Because Britain and France are the two largest contributors to ELDO, both English and French are working languages in the consortium. The official ELDO logo carries the acronyms of both its English and French names. The French version CECLES stands for Conseil européen pour la construction de lanceurs d'engins spatiaux, which is a bit of a mouthful! It’s going to be really interesting to see if all the member countries can overcome their different national rivalries and their different languages to make the complete Europa rocket successfully come together.

At least yesterday’s first test launch of the Blue Streak was a success. Although there was a problem with sloshing of the propellant as the fuel tanks emptied which caused the rocket to roll about quite a bit in the last few seconds of its flight and to land short of its intended target zone, the instrumentation along the flight corridor acquired a huge amount of useful information about the rockets performance. I was so thrilled with the news of the Blue Streak flight that I even phoned my former supervisor Mary Whitehead last night to hear more about it (and I’m going to have to give my sister the money for that long-distance trunk call, which I’m sure will be expensive).

Mary was at the Range for the launch and she told me that the rocket looked spectacular as it rose up into the blue sky out of its cloud of orange exhaust. She’s especially proud of the fact that the zigzag pattern you can see on the Blue Streak was her idea. It enables the tracking cameras to make very accurate measurements as the rocket rolls after leaving the launchpad. Using the pattern, the cameras can easily measure if, and how far, the rocket rolls depending on where that diagonal was relative to the top and bottom stripes. I know she’s looking forward to seeing how well this worked.

I’m looking forward to the next test flight, and Australia's further involvement in the Space Age!

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[June 6, 1964] Going Up from Down Under (The launch of the Blue Streak rocket)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640606Blue-Streak-launch-672x372.jpg)

![[May 24, 1964] The Darkest of Nights… ( <i>June 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640528Darkest-book-club-1964-423x372.jpg)

![[May 20th, 1964] Completing The Collection(<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Keys of Marinus, parts 4 to 6)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640520holmesasinsherlock-672x372.jpg)

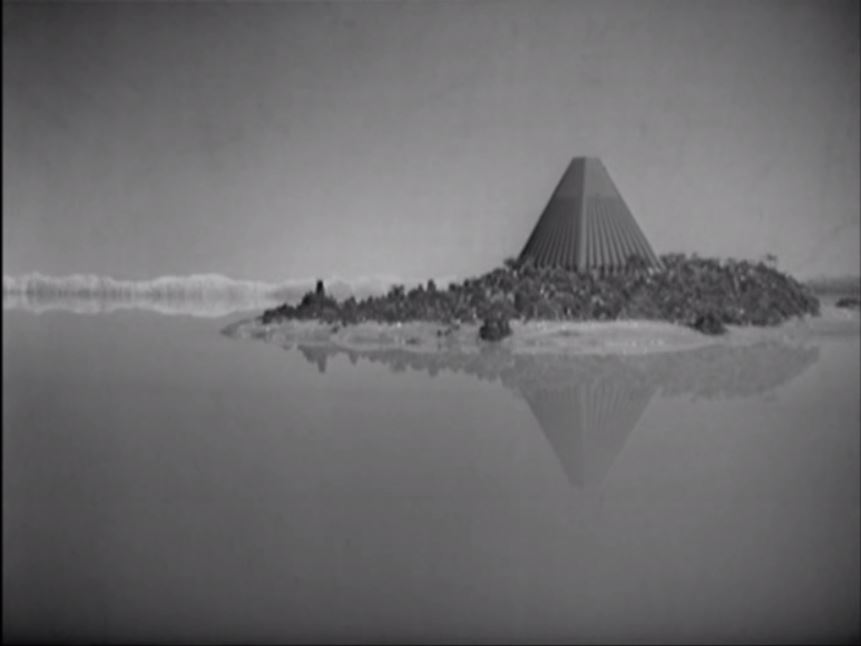

![[April 28, 1964] Out With the Old…. (<i>New Worlds, May-June 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640428cover-555x372.jpg)

![[April 26th, 1964] The Start Of A Wild Ride (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Keys of Marinus, parts 1 to 3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640426ilovebarbara-672x372.jpg)

![[April 8th, 1964] Pooooolo! (<i>Doctor Who</i>: Marco Polo, Parts 5 to 7)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640408costumes-672x372.jpg)

![[March 27, 1964] The End of an Era? Not With a Bang…. ( <i>New Worlds, April 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640327cover-409x372.jpg)

![[March 15th, 1964] Maaaarco! (<i>Doctor Who</i>: Marco Polo, Parts 1 to 4)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/640315butwherearethelittlehorses-672x372.jpg)

![[February 27, 1964] Beatles, Boredom and Ballard ( <i>New Worlds, March 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640227cover-649x372.jpg)

![[February 19th, 1964] The Edge Of Disappointment (<i>Doctor Who</i>: The Edge Of Destruction)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/640219stabbystabby-672x372.jpg)