by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

Quick recap, then. You might remember that last time I said that I thought that New Worlds and its editor Mike Moorcock were pushing boundaries, although I did say that this was not new and actually has been going on for a while.

Well, it now seems that people who don’t normally take an interest in such things have suddenly become aware.

With the last issue, newsagents W. H. Smith and Sons, Britain’s biggest newspaper and magazine vendor, in collaboration with John Menzies, refused to distribute the magazine on the grounds of ‘obscenity and libel’. The national newspapers here have got hold of this story and talked of W. H. Smith’s ‘ban’.

It's not actually clear what in the issue is obscene and libellous – I'm thinking that it'll probably be the sex in Bug Jack Barron, although the mind-rape poem for me was particularly unpleasant. But I guess that it'll be Moorcock off to court to defend the magazine.

It is possible that such a raised awareness of interest might improve sales, if only for a little while. (Remember the fuss over 'Lady Chatterley's Lover'? ) “No publicity is bad publicity”, so the saying goes. But this does assume that buyers can get hold of the issues in the first place.

This may then affect the production of future issues. Obviously, I will let you know more as and when I hear it.

Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

Cover by Stephen Dwoskin

Lead in by The Publishers

The “What-Used-to-be-Editorial” has lots of in-house stuff this month. As well as writing about the authors and artists in this month’s magazine (Butterworth, Disch, Koutroubousis), it also brings readers up to speed with what’s been going on – namely that in the last twelve months there’s been the loss of the publisher and the Arts Council grant. The magazine is surviving on £400 per month, but promises a bigger issue with colour next month. There’s new staff too, in the persons of James Sallis (mentioned last month) as fiction editor, Douglas Hill as associate editor, and Diane Lambert in charge of publicity. (Does this explain the lack of nakedness on the cover this month? Possibly. We’re almost back to those strangely obscure covers of the Carnell era!) Big plans, but let’s see what happens.

Dr. Gelabius by Hilary Bailey

The welcome return of Hilary as a fiction writer, whose duties of late have been more to do with editing New Worlds than writing stories.

Dr. Gelabius is some strange Frankenstein-ian story of a scientist disposing of a set of foetuses before being shot and killed by an irate mother. Comments about evil scientists, abortion and the death of Science no doubt go here. It’s short, and wants to shock.

Unfortunately, its brevity makes it feel as if it is part of a story rather than a self-contained narrative. I don’t think that it is Hilary’s best. The fact that the artwork for this dates back to 1964 suggests that this one’s been lying dormant for a while – filler from the slush pile, perhaps. 3 out of 5.

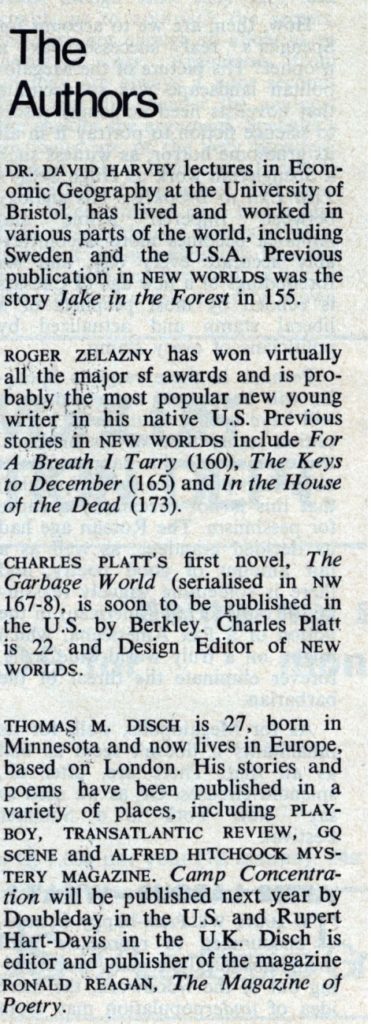

1-A by Thomas M. Disch

And now on to the return of another recent stalwart. 1-A is an anti- military story. The Lead-In suggests that the story is based on Disch’s bad military experiences whilst briefly in the US Army, and as stories go, I must admit that it doesn’t show the US military training in a positive light. Quite deliberately polemic. In style and tone it reminded me a lot of Camp Concentration, which it pales against, frankly, but it still gets its anti-war message across, even when the characters seem to be outlandish caricatures and their action nonsensical.

As the magazine is now being sold in the US, this seems to be deliberately provocative, as an attack on bravery, courage and also unthinking behaviour – and interesting in context, especially with the recent publication in the US of those lists of authors for and against the ongoing Vietnam War. 3 out of 5.

Bug Jack Barron (Part 4 of 6) by Norman Spinrad

As we’re now on part 4 – the extract begins with Chapter Eight – this may not be the best place to begin this story, despite their being a whole page summarising what has gone on before.

This time Barron confronts Benedict Howards, the powerful owner of the Foundation for Human Immortality, on his television show. Using the phrase “Deathbed is go” Barron sets up a situation live on television where Delores Pulaski begs for Harold Lopat, her critically ill and dying father, to be cryogenically frozen. After the advert break, Jack, in a gesture reminiscent of the Roman Emperors, then puts Howards on the spot live on air whether Lopat lives or dies.

Howards is savaged by Barron’s rhetoric, but off the air they agree for Barron to back off from giving Howards a killer blow in return for future covert discussion. Later, Barron refuses another request from Green to stand for the SJC. The next day Barron agrees to meet Howards face-to-face in his office, when Howards offers Jack and Sara free Freezer contracts in return for public support.

Later, after Howards then tries to blackmail Sara, she tells Barron about the deal with Howards that she made.

This part seems a little more sedate than the overheated sexual escapades of the last issue. But whilst I admit that the repartee is clever and the ranting impressive, the whole part feels bloated and just too long – behind all of the anger, it seems to take a LONG time to go anywhere.

Will it win more readers? Probably not. But I must admit that after four issues I’d like to see how this ends, even if I feel that the story should have finished by now. 3 out of 5.

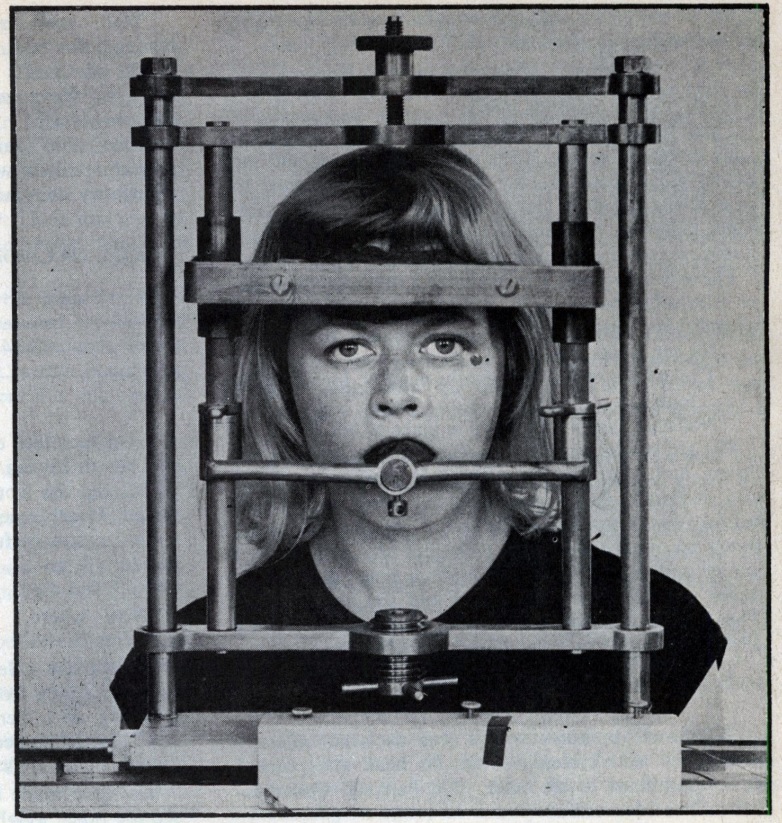

Article: The Mechanical Hypnotist by Dr. John Clark

Article time. Dr. John Clark tells us about hypnotism and how being the non-participant observer has improved his study. It was quite hard going to read, although quite interesting. I seem to remember Brian W. Aldiss’s Report on Probability A back in the March 1967 issue using such a technique, or at least discussing using such a technique.

Weather Man by James Sallis and David Lunde

And following on from a discussion on observational techniques, we have a story that is about observation. Weather man reports events such as the weather on a day when the reporter/observer watches a young lady from afar, then a storm, before things return to normal, although the effect on the young woman seems to suggest that there is more than meets the eye happening here.

Written in a lyrical stream-of-consciousness, it is not quite poetry and not-really-narrative. At least it is linear in presentation! Seeing as how Sallis has now become ‘Associate Editor’, I suspect we’re going to see more of this style of story in the future. 3 out of 5.

The Man Who Was Dostoevsky by Leo Zorin

And talking of observational reportage… new author Zorin describes events in that detached-observer mode we have already spoken of, as seen by ‘ Word System Number One’. He describes his surroundings and elements of his earlier life – his sister, his lover, a professor – in short, clipped sentences, such as ‘He drinks coffee.’

The kick is that it is revealed over the length of the story that the narrator is in some short of shock after events in some sort of post-apocalyptic world. The phrases and statements given in such an understated manner mean that the awful events described – talk of sex and penises, rape and murder – are designed to shock. Better than I thought it was at first going to be. 3 out of 5.

OK. So, I guess that the joke here is probably that regular readers will know that the so-called ‘New Wave’ often looks at fiction in new forms. This ‘story’ by Sladek is set out on the page as a blank test paper, to be completed. It’s a new form – get it?

Whilst what is required in order to answer the paper becomes increasingly surreal and nonsensical, that’s about as good as it gets. Novelty rather than gravity, but it at least makes a point. 3 out of 5.

Concentrate 2 by Michael Butterworth

After Concentrate 1 (published in the New Worlds of August 1967), we now get Concentrate 2. It rather defies description (of course!), but it is another story a la J. G. Ballard that’s cut up into sections. (I’ve heard a rumour that Ballard was involved in editing this down from longer works, which would make sense.)

The allegory, for what it’s worth, seems to involve God-like creativity and chaos. Really though, it is little more than what we’ve had before – lyrical prose, designed to shock with its talk of sex, ‘niggers’ and religion. Graphic imagery and violence, all trying to mean more than it does.

To be fair, Butterworth’s stories and poetry have a lot of fans, including Moorcock. Unfortunately, I’m just not one of them. Rather than being innovative and interesting, this was tiresome for me. 2 out of 5.

The Valve Transcript by Joel Zoss

As the title suggests, this is a tale in the form of a transcript about an incident involving the fixing of a valve on an underground pipe. It’s dangerous work, costly to suspend but well paid. All seems rather mundane and low-key in conversational prose. Really not sure what its point is, which may be the point! The reason why the author's name is emblazoned on the front cover of the issue is a mystery to me – like the Bailey story, earlier, this one feels like filler. 2 out of 5.

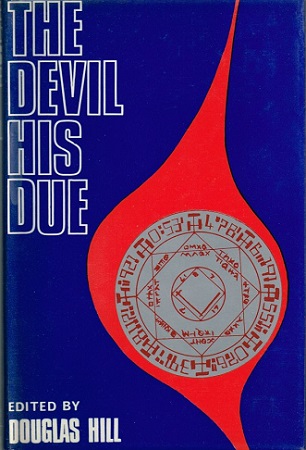

Article – The 77th Earl – A review of Titus Groan by Mervyn Peake by Langdon Jones

Langdon Jones continues to herald Meryvn Peake’s work (see also the article in New Worlds October 1967). This time Jones is concentrating on the first book in the Gormenghast series, Titus Groan, with a little mention of Peake’s book for children, Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor, all of which are being published or republished.

I must admit that for me Peake’s work still impresses, with Jones’s analysis doing a good job of illustrating the key elements of Peake’s prose, and some of Peake’s accompanying artwork quite chilling. Reading this reminded me further that part of Langdon Jones’s own story published last month, The Hall of Machines may have been inspired by Peake’s work. 4 out of 5.

Book Reviews – From The Outside In by James Sallis

And in the absence of poetry, we have reviews of poetry – four books of poetry and two novels reviewed by Sallis this month, none of which are genre. Despite Sallis’s attempts to persuade me of the poetry’s beauty, I remain stubbornly unmoved.

Summing up New Worlds

Is it me or does this issue feel a little less manic than the last? Are we in a holding pattern whilst new boys Sallis and Hill find their feet?

Whilst there are elements that still try to push people’s buttons, my general impression of this issue is that it feels relatively safe. There’s no cut up art shenanigans from Charles Platt, and although we have more poetic allegory, there is no poetry. The what-now-seems-typical use of shock language, usually to do with sex, race and religion, is included, but the overall cumulative effect seems to lessen the impact of such violent, unpleasant words.

Similarly, we have a lot of New Worlds regulars, with some new names, admittedly, and whilst some of the topics (Disch’s anti-war rant) and the language (see Bug Jack Barron) may still be controversial, much of the material actually doesn’t feel like anything new.

We have two pieces that feel like they’re there to fill up space, the Peake article is on an author we’ve seen before, the Disch just reads like an extension of the ideas in Camp Concentration to me, and the Butterworth a less worthy imitation of Ballard.

As shown by those middle-score marks out of 5 throughout, this issue may not be as much of a scandal as some might think the magazine could (or should!) be. Whilst it is perhaps a good summary of where New Worlds is at today, despite protests to the contrary this issue seems to push fewer of those boundaries.

Anyway, that’s it, until next time.

![[March 26, 1968] Scandal! <i>New Worlds</i>, April 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/New-Worlds-April-1968-672x372.jpg)

![[November 26, 1967] The Shock of the New – Part 3 <i>New Worlds</i>, December 1967 – January 1968](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/new-worlds-dec-67-672x372.jpg)

Carnaby Street, London: where's the snow?

Carnaby Street, London: where's the snow?

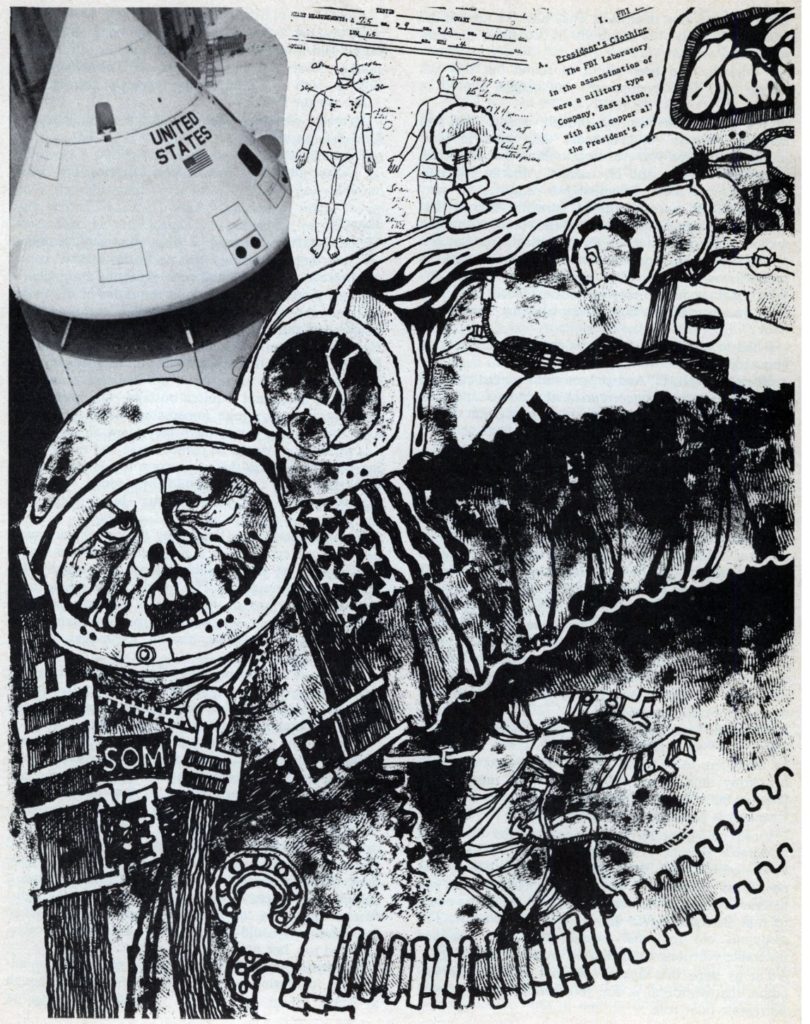

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch

Cover by Eduardo Paolozzi, designed by Charles Platt and Christopher Finch Example of one of the pages of Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton art.

Example of one of the pages of Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton art.

There's quite a few missing here!

There's quite a few missing here!

![[October 24, 1967] War, Anti-utopias and Near-Future Apocalypses <i>New Worlds</i>, November 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/New-Worlds-November-1967-672x372.jpg)

Cover by Vivienne Young

Cover by Vivienne Young An example of the logic shown in this article. Not sure I understood this!

An example of the logic shown in this article. Not sure I understood this!

Example of Self's imagery.

Example of Self's imagery. Uncredited image, but it looks like a Douthwaite, who is credited in the magazine.

Uncredited image, but it looks like a Douthwaite, who is credited in the magazine. Another uncredited image that looks like a Douthwaite.

Another uncredited image that looks like a Douthwaite. Sharing the horror in full – another poetic gem – well, they seem to be liked by some!

Sharing the horror in full – another poetic gem – well, they seem to be liked by some! Illustration by Cawthorn

Illustration by Cawthorn The future of energy?

The future of energy?

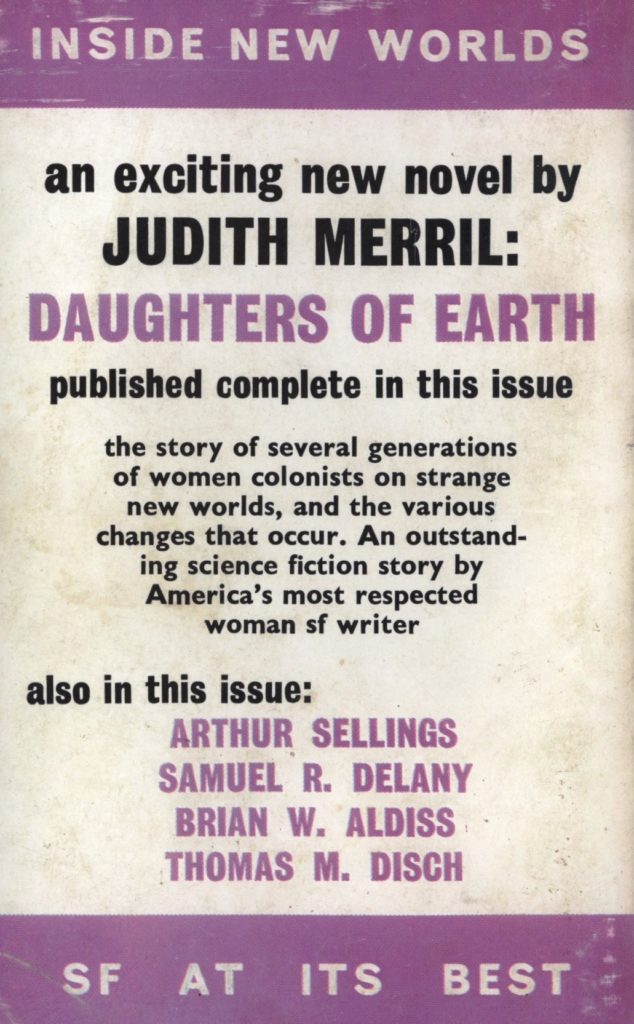

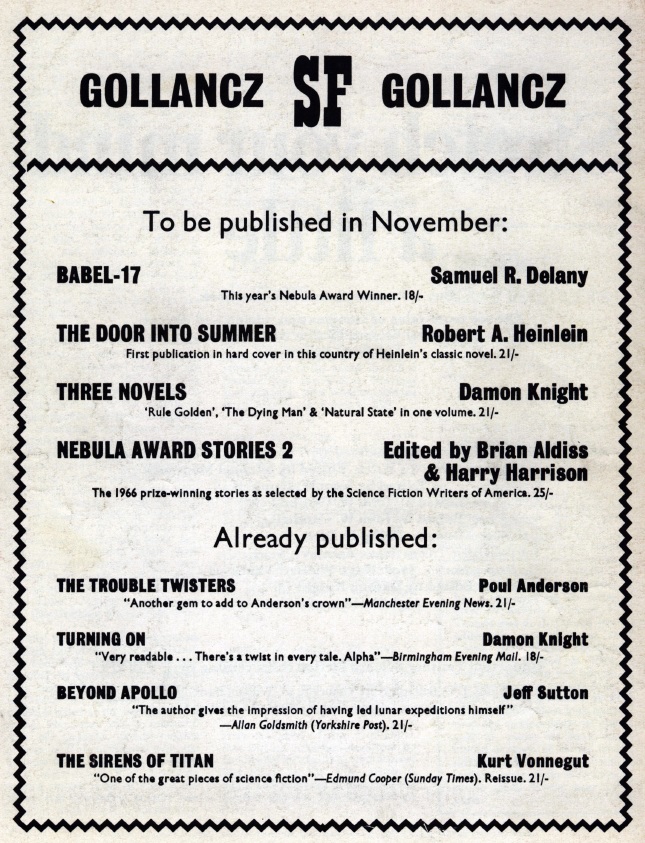

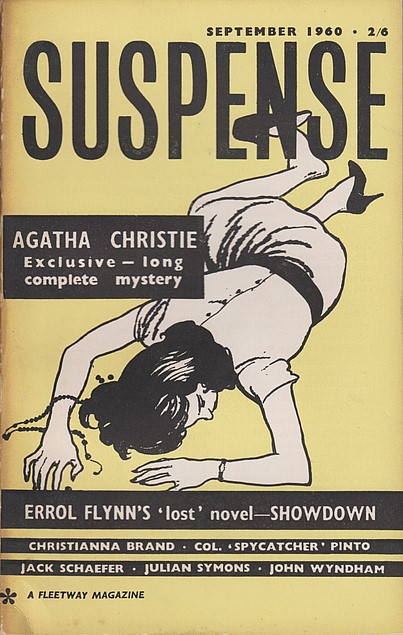

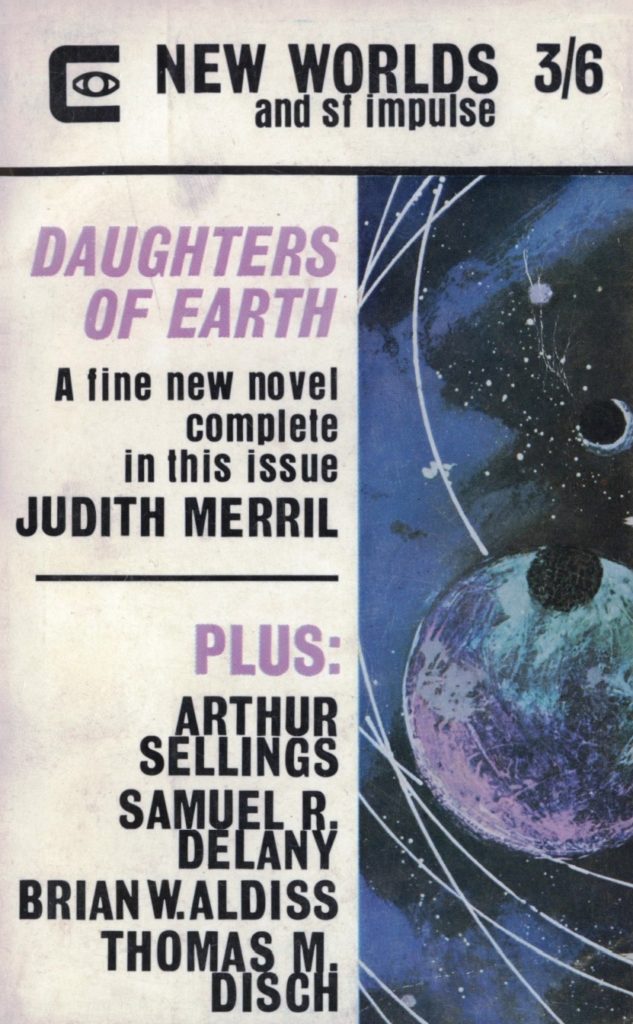

An advertisement from this month's magazine that shows how different book sales and New Worlds magazine is, perhaps? How many of these authors are mentioned in detail in the magazine these days?

An advertisement from this month's magazine that shows how different book sales and New Worlds magazine is, perhaps? How many of these authors are mentioned in detail in the magazine these days?![[September 26, 1967] Anniversary? Really? <i>New Worlds</i>, October 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/NW-October-1967-672x372.jpeg)

Yes: people are willing to go to war over Baked Beans!

Yes: people are willing to go to war over Baked Beans! A page showing some of Peake's imaginative artwork.

A page showing some of Peake's imaginative artwork. This illustration seems to sum up this odd story.

This illustration seems to sum up this odd story.

![[August 26, 1967] The Shock of the New II – Sex and the Modern British SF Reader <i>New Worlds</i>, September 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/New-Worlds-cover-Sept-67-672x372.jpg)

![[August 6, 1967] A Dark Future (<i>The Devil His Due</i> by Douglas Hill)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Devil-His-Due-2-306x372.jpg)

![[July 28, 1967] The Shock of the New – Rabbits, Hedgehogs and Kazoos (<i>New Worlds</i>, August 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/NW-September-1967-672x372.jpg)

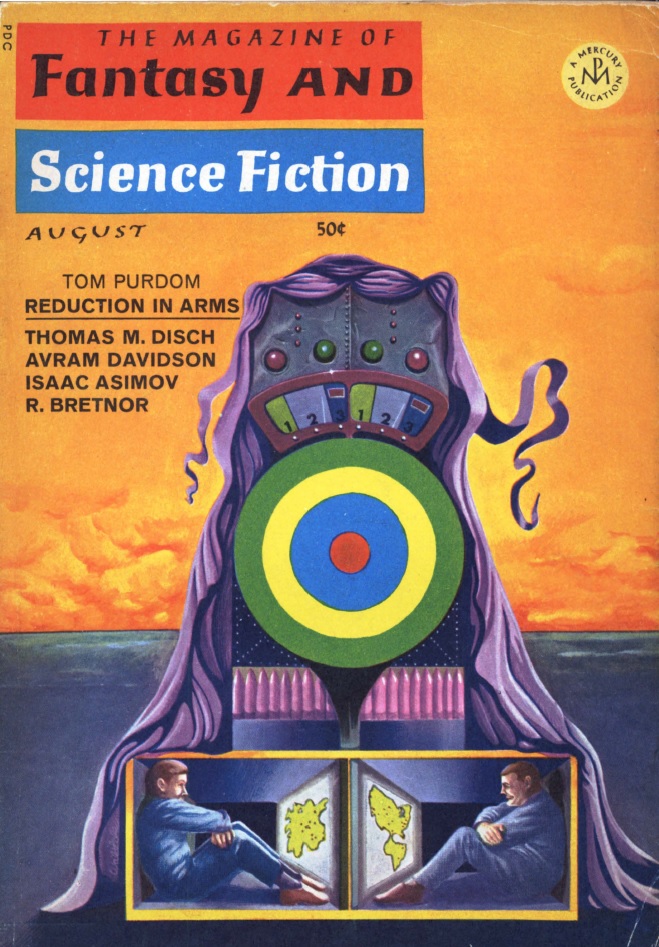

![[July 20, 1967] An Analog of <i>Analog</i> (August 1967 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670720cover-659x372.jpg)

![[June 26, 1967] Change is Here (<i>New Worlds</i>, July 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/New-Worlds-cover-July-1967-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by Zoline

Illustration by Zoline

![[March 26, 1967] Changes Coming <i>New Worlds and SF Impulse</i>, April 1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/New-Worlds-April-1967-672x372.jpg)

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Illustration by James Cawthorn