by Mark Yon

Scenes from England

Hello again!

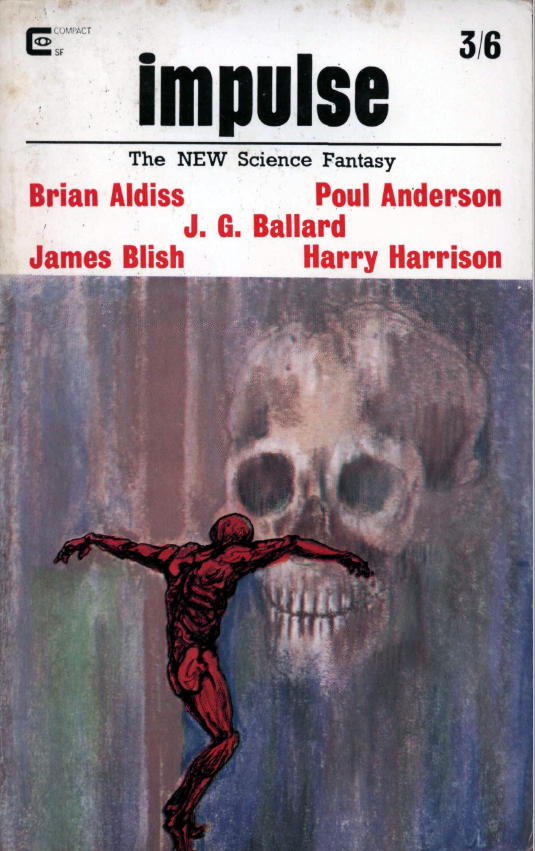

Well, after last month’s rather enthusiastic response from me – most unusual, honestly! – with the emergence of Impulse, “The NEW Science Fantasy”, I was very interested to see if it could keep up the standard of last month’s issue.

Having graced us with a cover from Mrs Blish last month, this month’s Impulse cover is back to the usual of late by using a Keith Roberts cover to illustrate his latest story in this magazine. Well, as the recently-promoted Mr Roberts is now the Associate Editor, why not? Presumably there’s a discount for using all these elements…

Kyril, the Editor, is in pensive mood this month. He professes that after two years he is still not sure what to write in the Editorial, but then goes on to give brief descriptions of this month’s stories before mentioning that he has concentrated on four longer stories this time, which has led to less “typically Bonfiglioni space-fillers”.

To this month’s actual stories.

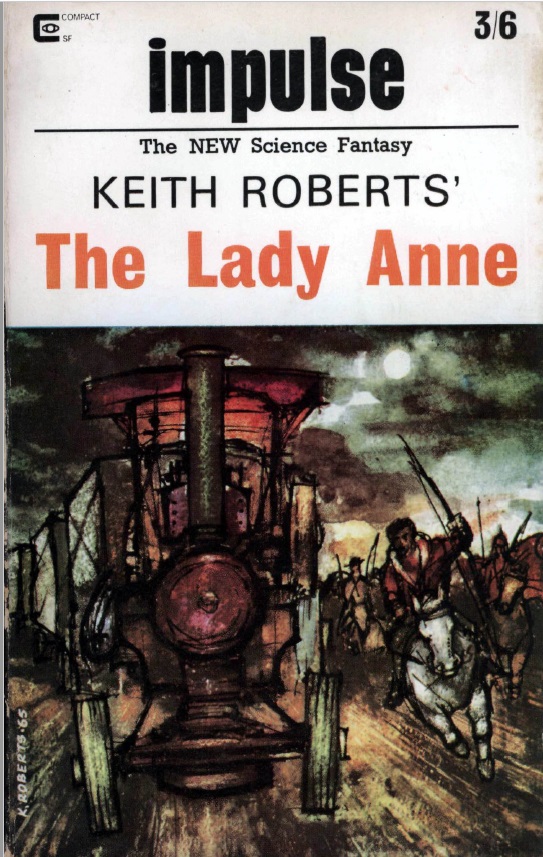

Pavane: The Lady Anne, by Keith Roberts

I really liked Keith’s alternate history story last month, despite the odd ending. It has been hinted that this was the first of a series, and here is the second, now elevated to prime position in the magazine. As I said last time, and is made explicit this month, the premise is that Elizabeth I was assassinated in 1588. As a result, Protestantism has not taken hold in England and Roman Catholicism still dominates the world. With the Roman Catholic view of science being one of suspicion, and innovation suppressed, inventions have not as developed as they have been here today.

This time the story focusses on a life on the road, being centred around the Lady Anne, a steam tractor that moves goods from settlement to settlement along the roads of the predominantly rural Britain. It’s not an easy life – the cover suggests one of the challenges! – but there’s a real feeling of a way of life that is not dissimilar to that of the ancient mariner or the locomotive driver of Edwardian England. Keith’s vivid imagination describes what life could be like in this alternate history in a way that made me feel like I was there. Although there’s a rather clumsy attempt to tell of a doomed and unrequited relationship between Jesse the tractor driver and a woman in the town of Swanage which sits uneasily, this is a good start. 4 out of 5.

A Last Feint , by John Rackham

Another regular. John was last seen in the January issue of Science Fantasy with his Weird Tales-type story The God-Birds of Glentallach. This time the story is a much lighter one, about an inventor who attempts to invent a cheap vest and foil for fencing electronically but inadvertently creates a weapon that can slice things in half. This month’s silly story in Impulse, and the weakest. 3 out of 5.

Break the Door of Hell, by John Brunner

Having mentioned in New Worlds last month how much more we’re seeing of John Brunner of late, here’s a novella from the man. And whilst last month’s serial in New Worlds was OK (more about that later), this one is terrific.

Break the Doors of Hell is a fantasy story about a nomadic traveller, who has many names, who seems to be journeying from place to place and at different times to bring Order in an eternal battle between Law and the forces of Chaos. It is a great idea. I could see Mike Moorcock liking it, for it has that same mythical tone to it that the Elric stories have.

To bring Order, the Traveller travels across the All, giving people what they ask for, although the first part of the story shows that the result is often not what the requester wishes for.

Most of Break Down the Doors of Hell is about the Traveller visiting the once proud and pretty city of Ys, which now seems to be a place of decay where the inhabitants live a life of amoral decadence and decline. Led by Lord Vengis, they blame this decline on the city’s founders and wish to contact them, though long dead, to reprimand them. This does not go well.

Break the Doors of Hell is extravagant in its portrayals of decline and excess, giving vivid descriptions of the setting and the characters therein. There are cannibal babies, hints at bestiality and shriekingly awful lords and ladies in positions of power, none of which are particularly nice, but which also means that their come-uppance at the end is perhaps more satisfying.

Imaginative and definitely odd, this is quite different from the Brunner work I usually read, and different again from the other Brunner I've read this month. 4 out of 5.

Homecalling (Part 1 of 2) by Judith Merril

A few months ago I mentioned that both Moorcock and Bonfiglioli had said that as a result of talks at the London Worldcon we could expect fiction from Ms Merril in both Science Fantasy and New Worlds soon. And here it is. Kyril in his Editorial claimed that it is perhaps the best story in the issue.

Unfortunately, my own excitement was tempered by the fact that this is not “new” fiction but a reprint from Science Fiction Stories back in November 1956. Even more annoyingly, although the back cover claims that it is a complete short novel, it is actually only the first part of the story, to be continued next month. It is perhaps understandable, though. Ms Merril currently spends most of her time currently dissecting books in her reviews in The Magazine of Fantasy and SF. and The Year’s Best SF anthologies and presumably has little time to write new fiction.

We begin with what appears to be a family – mother Sarah, father John, daughter Deborah (also known as Dee) and baby Petey. However, their spaceship crashes on a strange planet and Dee is left with Petey to survive. After some exploring, Dee finds the home of the insect-like Lady Daydanda, who lives in a hive-like colony. After First Contact, Dee and Petey are persuaded by telepathy to be rescued by Daydanda’s hive, who take them back to their home. Daydanda as a Mother and a Lady of a Household is fascinated by them, especially as they seem to have travelled beyond the skies. The end of this first part leads to Dee and Daydanda meeting and, despite Dee’s initial and understandable reluctance, communicating with each other.

The character of Dee is lovely – a nine-year old who is brave, strong and resourceful in a way that I usually only see Heinlein achieving. She is no child prodigy, though, and Merril does well to make her seem like a nine-year old and not a child wunderkind. However, the triumph of this story is that through Daydanda, Merril manages to create aliens whose thoughts and concepts are logical and yet definitely alien. Daydanda’s initial mistaken ideas about Dee and Petey are understandable given the nature of her race, but much of the latter part of the story shows her resourcefulness, bravery and intelligence as she tries to both look after the orphaned children and understand them.

The story’s definitely worth reading, but like the reprint of Arthur C Clarke’s Sunjammer story in New Worlds in March 1965, it takes up space that could perhaps be better filled with new material. Therefore, although it is, as Kyril suggests, one of the best stories in the issue, I have removed one mark from my original score to make it 3 out of 5.

Summing up Impulse

The stellar group of authors in last month’s issue have been superceded by a smaller group of more varied and less well-known writers.

This could be seen as a return to normal, of going back to basics, and as a result a bit of a let-down. It doesn't help that the Merril is half of a reprint.

However, despite there only being four stories in this issue, I am impressed by the quality of what’s on offer. At least three out of the four are great, whilst the Rackham is a little bit of a placeholder, I’m afraid. Nevertheless, this is a good issue.

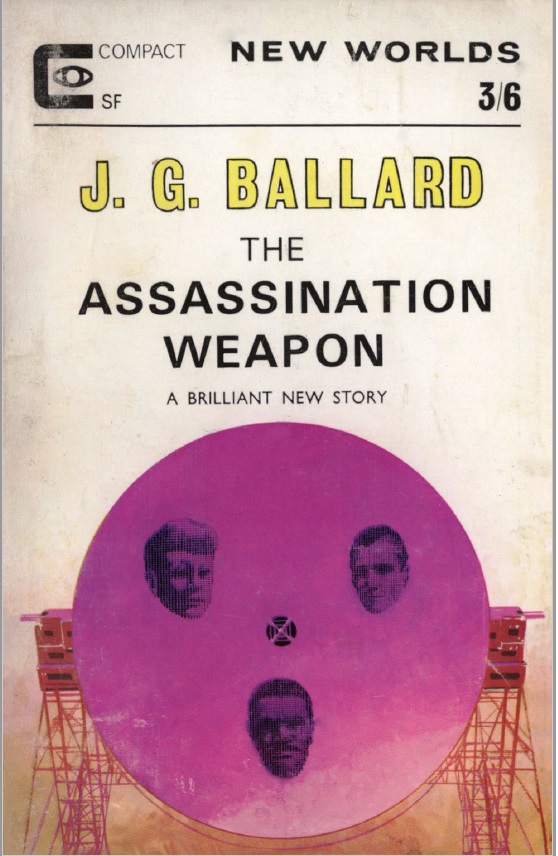

The Second Issue At Hand

Editor Mike Moorcock does not have Kyril’s crisis of confidence this month. He spends his time talking about the difference between ‘truth’ and ‘untruth’, which for most sf writers is difficult, involves total intellectual and emotional detachment and discipline. The reason for this musing is to allow Moorcock to suggest (again) that the best of the ‘new SF’ does this, unlike the ‘old’, and then use that point to say how good JG Ballard’s story in this issue is. That cover is awful, though.

To the stories!

Illustration by Unknown

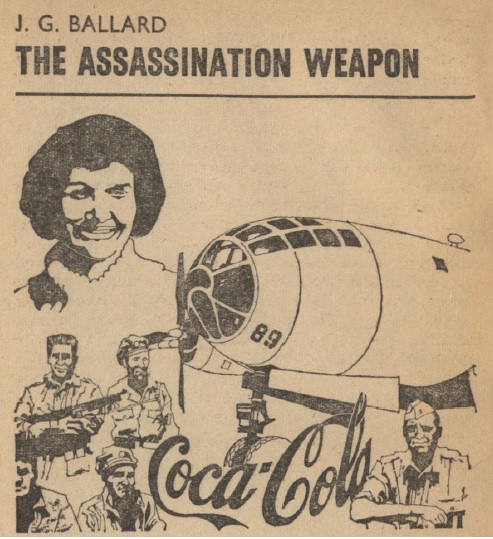

The Assassination Weapon, by J G Ballard

After his book reviewing in New Worlds and his story in Impulse last month, we have a return to fiction by Ballard in New Worlds.

There has been an interesting trend in the New Wave fiction in recent months. Moorcock’s done it as James Colvin, referencing Eva Braun and Adolf Hitler in a story in the September 1965 issue, and Richard Gordon brought the Marquis de Sade back to a trial in the November 1965 issue. Here JG manages to use JF Kennedy, Harvey Oswald and Malcolm X in a much darker story, connecting them together in his usual cut-up disparate fashion.

My understanding of the story may be unclear. I get the vague impression that this one may even be beyond me, but Moorcock in this month’s Editorial summarises the story by saying that Ballard ”questions the validity of various popular images and modern myths which remain as solid and alive as when they were first given concrete form in the shape of the three assassinated men who continue to represent so much the atmosphere of their times. Ballard does not ask who killed them, but what killed them – and what combination of ideas and events created and then destroyed them?”

To do this Ballard writes a number of short paragraphs from different perspectives, all evoking people we ‘know’ and sometimes images Ballard has used before – the terminal beach, decaying cars, cityscapes – in a dazzlingly assembled group of seemingly disconnected elements which together form a patchwork of a story.

Personally, I am torn between admiration of such a bold idea and a feeling that the story is just taking American culture and trying to shock. The fact that Moorcock has to explain to me what the story is about, rather than me being able to work it out for myself, is a minus.

Despite this, Ballard has imagined a deliberately controversial story here that will confuse many (like me) yet at the same time make the reader think. Therefore typical Ballard, on form. 4 out of 5.

Skirmish, by John Baxter

The return of Australian John Baxter, last seen in these pages back in February 1965 with More Than A Man. This is the story of a hopelessly damaged spaceship, the Cockade, and the remaining crew’s attempts to finish their mission and survive against the alien Kriks. Well written but predictable Space Opera. It’s a bit of a relief after the intense Ballard, frankly. 3 out of 5.

No Guarantee, by Gordon Walters

We’ve met Gordon before with his story Death of an Earthman in New Worlds in April 1965. You may know him as George Locke. No Guarantee is a comical attempt to publish a monograph about the Moon landing but along the way discusses Literature and the members of the “Leicester Literary Longhairs”. The overall point of the story to me seems to be “Don’t go to the Moon!” It is written almost as a stream of consciousness, part comedy, part horror story, but the combination seems forced and it doesn’t really work for me. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

House of Dust, by Norman Brown

Yet another new name. Another post-apocalyptic tribe story about a group’s struggles to eventually return to the deserted city of their past. Not particularly original. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by Douthwaite

The Ruins, by James Colvin

James’s first story since the serial The Wrecks of Time, which started really well but disappointed me in the end. Here Maldoon is wandering in a set of ruins. He seems to encounter a city with cars, people and cafes, and then stranger things but in reality all of this seems to be hallucinations experienced whilst in the ruins as his mind breaks down. More drug related allegory that didn’t really mean a lot to me. Again, Colvin's story isn’t really bad but fails to excite. 3 out of 5.

Cog, by Kenneth Harker

A new writer to me. The title suggests something that is part of bigger machinery, but actually the word Cog is short for “cognito-handler”. Or at least I think so. Through this story there are a number of alternatives suggested – Chaser of Gloaming, Chance Orbit Gambler, Clerk Ordinary Grade, even Castor Oil Gargler. It is a mildly amusing joke that overstays its welcome and attempts to cover up the fact that this is an overworked satire. 3 out of 5.

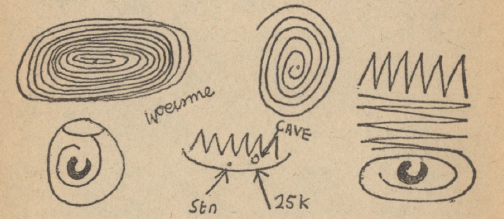

Eyeball, by Sam Wolfe

Another new writer. A short but deliberately lyrical story about an Earthman from planet Alpha 762 who is the involuntary host of an invading Martian spaceship inside their body – actually, in one of his eyeballs – to gain intelligence before invasion.

There’s some wonderfully florid descriptive passages here. Try the first few lines as an example: ”Irritation surrounds the glowing softness, the jelly mass light sponge crisping in the raw sunlight attack. The red streaked itch and harsh grains of invisible sand dust. Ganglion strands sucking away protective juice,” which I suspect you will either love or, like me, feel that it is a little overworked. A story of style over substance, perhaps. 3 out of 5.

Illustration by James Cawthorn

Consuming Passion, by Michael Moorcock

A story about a man known as “Pyro Jack”, who can set off fires at will and does so across London for fame and triumphant recognition by the police and public – a sort of pyromaniac Jack the Ripper! He is arrested but escapes to a library, determined to make his last act memorable. Wonder what Ray Bradbury would make of this one? 3 out of 5.

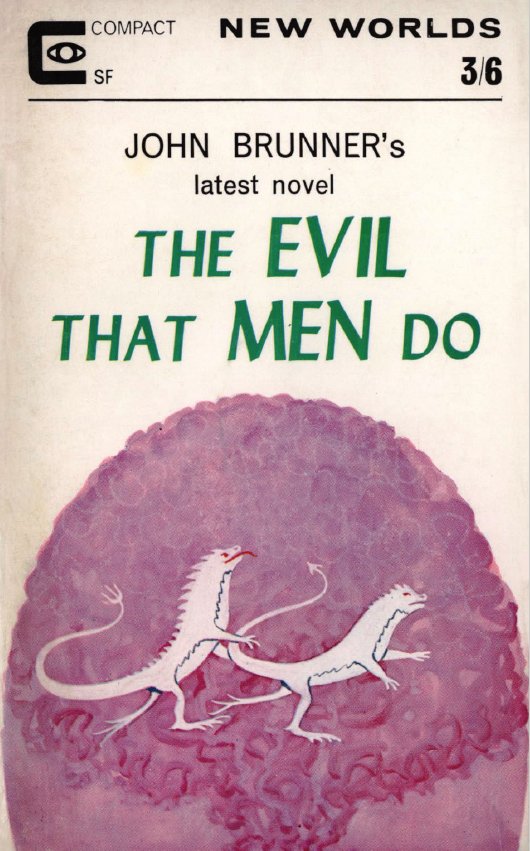

The Evil That Men Do (Part 2)), by John Brunner

The second part of Brunner’s creepy story now. If you remember, Godfrey Rayner’s party-piece was that he is a hypnotist. When he puts reluctant Fey Cantrip into a trance she talks of a nightmare involving a white dragon. We found at the end that Rayner’s psychiatrist friend Dr. Laszlo has a patient with what sounds like the same dream.

This month Godfrey tries to get more about Fey’s background in order to help her. He talks to her few acquaintances and meets the patient Alan Rogers in Wickingham Prison. Through hypnosis Rogers reveals a sad and perverted background that seems to be centred on a pornographically explicit book, The Harder Dream by Duncan Marsh. To try and get to the bottom of the issue and help Fey, Godfrey travels to Fey’s original home in rural Market Barnabas, where we find that Fey has also had access to this book. The story ends in a fury of Weird Tales-ian psychosexual violence.

Last month I said that this is OK and read easily. This month the point of the story is revealed, as a sexual tale designed to shock. Whilst undeniably violent and sexually intense, It is still readable, but I much preferred the other Brunner on offer this month. 3 out of 5.

Articles and Book Reviews

First this month is an article from Bill Butler, he being the author of the poem From ONE in last month’s issue, which talks of William Burroughs and his work. As you may have noticed, since Moorcock’s uptake as Editor in New Worlds there has been a fairly regular indulgence in the deification of William Burroughs. We continue this here. Whilst I realise that there may be new readers to the magazine who may not have read this before, the long-term readers (of which I see myself as one), will recognize it.

Two points sprang to mind after reading this – one, the first part of the review does little more than summarize what J G Ballard said in issue 142, which, although relevant, rather bores those of us who have been here before, and second, it’s never a good idea to spend paragraphs explaining why Burroughs is deliberately obtuse and then berate fans of his work for not understanding his writing. I appreciate the enthusiasm of the article, but this feels like what you Americans call “a puff-piece” and so undoes the promotion that it seems to be trying to do.

George Collyn then continues this look at New Wave writers by examining the work of Kurt Vonnegut. Because I haven’t read this before, although it is not the first time Mr. Vonnegut has been mentioned lately in this magazine, I was more interested. Collyn points out that if Ballard is the British version of New Wave the Vonnegut is the American. Personally, I disagree (I think Zelazny, Ellison, and Samuel Delany fit the description, myself), but I understand the point he is trying to make. Like Ballard, Vonnegut plays with form and writes in a way that is not what most people may think of science fiction, even when there are elements within. Reading this article further I’m fairly sure Vonnegut doesn’t think he writes science fiction, either. The rest of the essay is expectedly rather gushing.

Assistant Editor Langdon Jones, under the intriguing title ‘Wireless World’ Strikes Again reviews Voices from the Sky by Arthur C Clarke. As one of the old guard of writers, and as this is a book of non-fiction essays, I was rather expecting these trendy reviewers to denigrate the book. I am pleased to read that they are surprisingly complimentary. “Only Clarke (with the possible exception of Asimov) could write about Space Flight and the Spirit of Man without descending into dreadful pseudo-poetry and bathos.” It sells the book well, which may be the point.

There are no Letters pages AGAIN this month, though we are promised letters on Science vs Religion next time.

Summing up New Worlds

In this 161st issue of 160 pages, there’s a lot to like, despite the dodgy cover. Moorcock has (deliberately, I think) gone for a wide range of stories, often from new writers. This was part of his mission statement a few months ago, and it is pleasing to see him keep to his word.

Unfortunately, whilst appreciating the chance to read new writers, many of the stories are clearly work from writers still learning their craft and frankly they are not always that good. The Colvin disappoints, the Moorcock is good, though a minor piece. The Ballard is the selling point this month, but one story does not make an issue. There’s a lot here that seems to be simply trying too hard, which is why I liked rather than loved this issue. It was a little ironic that I felt at the end that New Worlds had more “typically Bonfiglioni space-fillers” this month.

Summing up overall

Less of a difficult choice this month. Whilst both magazines still seem to be blazing a trail, and all the better for it, the relative inexperience of the work in New Worlds and the quality of the Keith Roberts and John Brunner in Impulse means that Impulse has my vote this month.

Next month, the return of Bob Shaw, a name we’ve not seen for a while, in New Worlds!

Until the next…

![[March 26, 1966] Steam Tractors and Ballardian Mind Games <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, April 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Imp-New-Worlds-April-1966-672x372.jpg)

![[February 22, 1966] A New Age? <i>Impulse</i> and <i>New Worlds</i>, March 1966](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Impulse-NW-March-1966-672x372.png)