by Gideon Marcus

To Boldly Go

In the days of the Gold Rush, the Forty-Niners staked out the most promising spots in the hopes of striking it rich. They set out across thousands of miles, making harrowing overland or overseas trips to California, setting wobbly feet in the land that would soon be The Golden State, hoping that a survey of their claimed land would be a promising one.

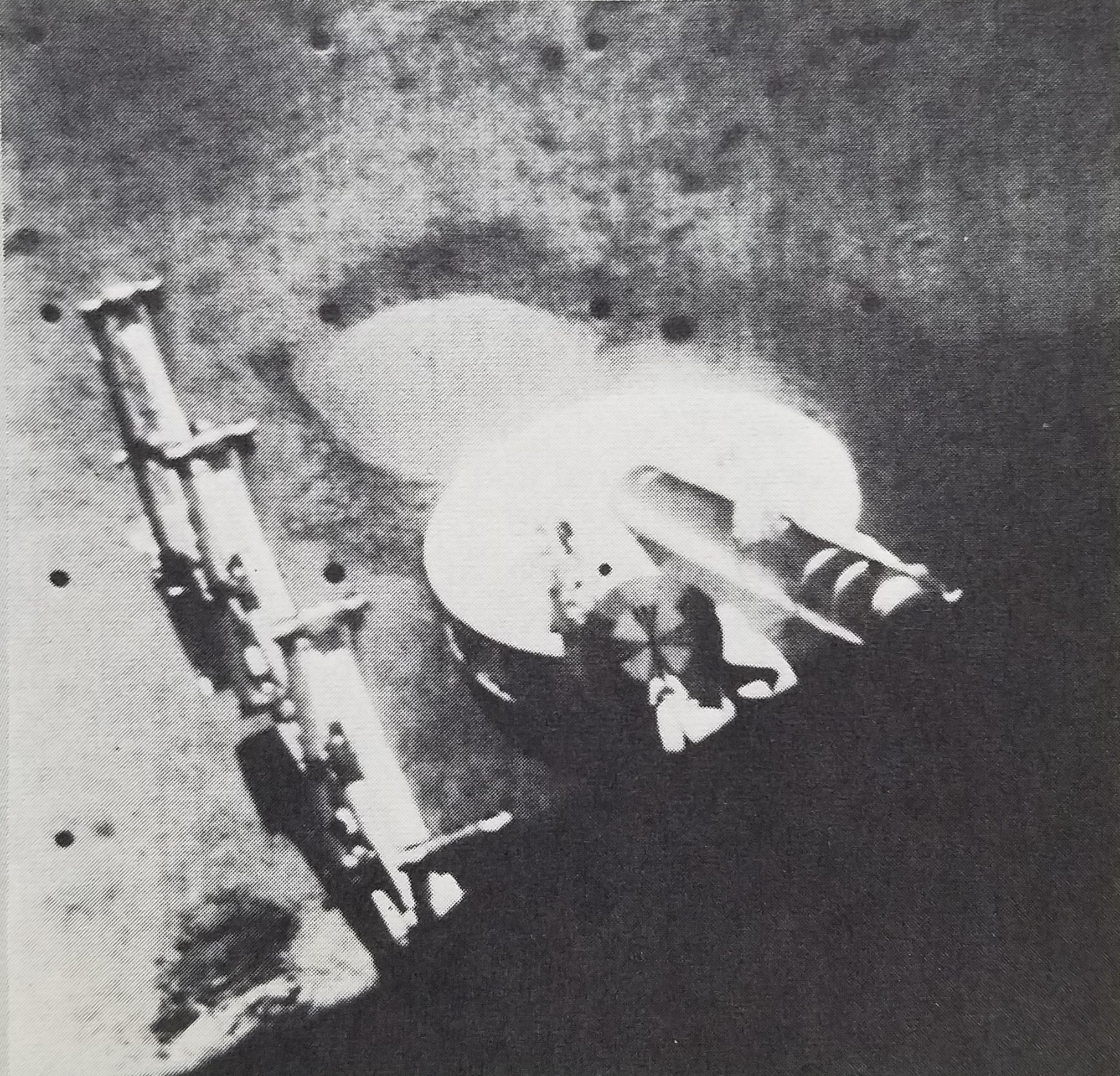

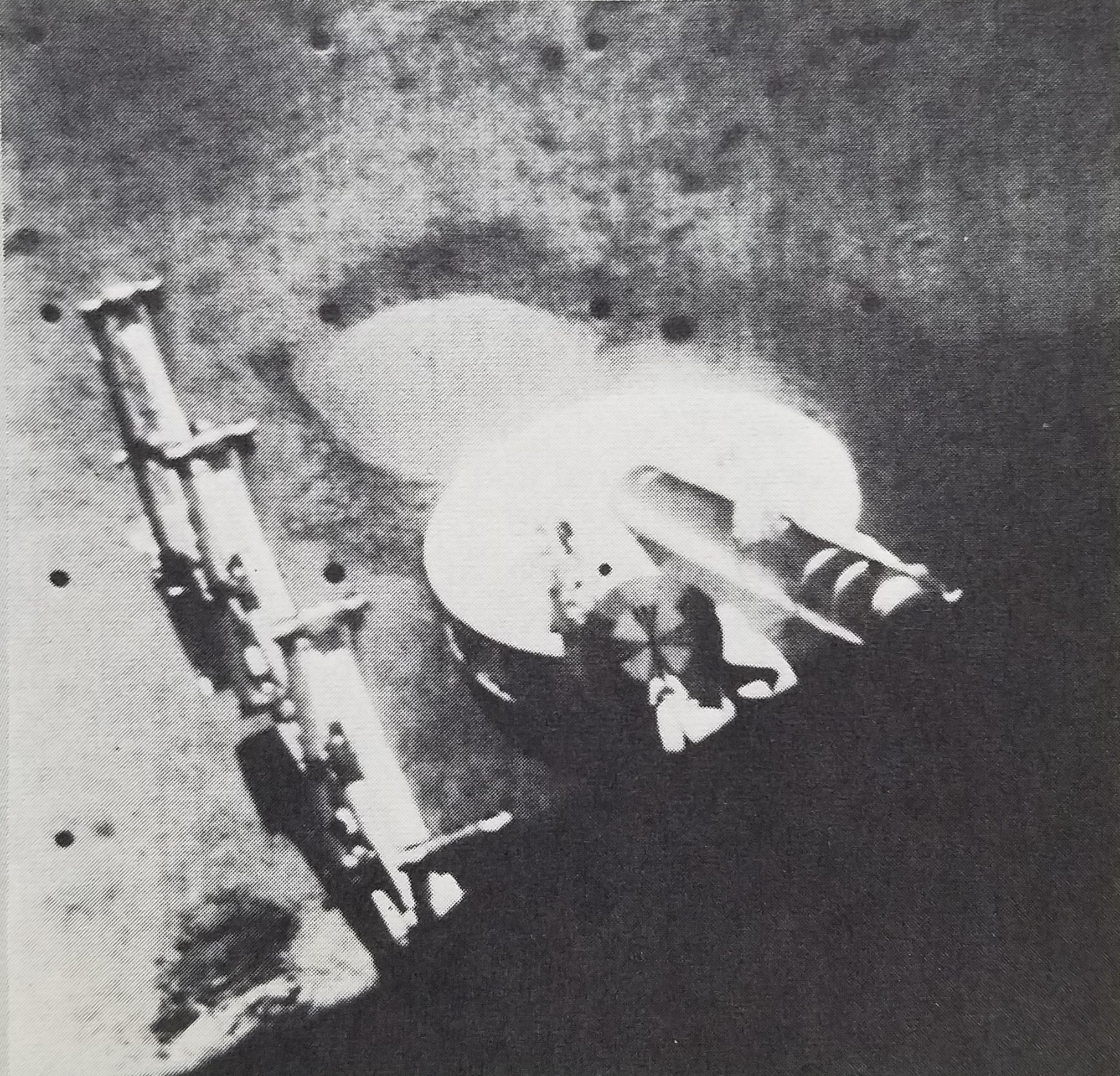

Two Surveyors have made their way to the Moon, the second of which (Surveyor 3–Surveyor 2 didn't make it) has just broken ground on our celestial neighbor.

While we can't pan for gold on the Moon (and, indeed, if there is a precious resource we're hoping to find there, it's water), Surveyor did spread lunar soil on a white surfaced background. This has allowed geologists…well, selenologists now…to make tentative guesses as to the composition of the Moon. More importantly, it has been categorically shown that the lunar surface is solid and can be landed upon by Apollo astronauts! Together with the photos from the several Lunar Orbiter spacecraft, the Sixty-Niners will have a good lay of the lunar land they'll be exploring.

By the way, the first Apollo crew has been chosen. These are the folks originally slated for Apollo 2, an orbital flight that would have flown a few months after the tragically lost mission of Apollo 1.

They are Walter M. Schirra, Donn F. Eisele, and R. Walter Cunningham. The first name should be a well known to readers; the other two are rookies from the third group of astronauts, folks recruited specifically for Apollo. It is unlikely that their flight will take place before 1968, and there will be at least one more manned test before the big jump to the Moon. There's currently even talk of a trip around the Moon before a landing attempt.

To Timidly Creep

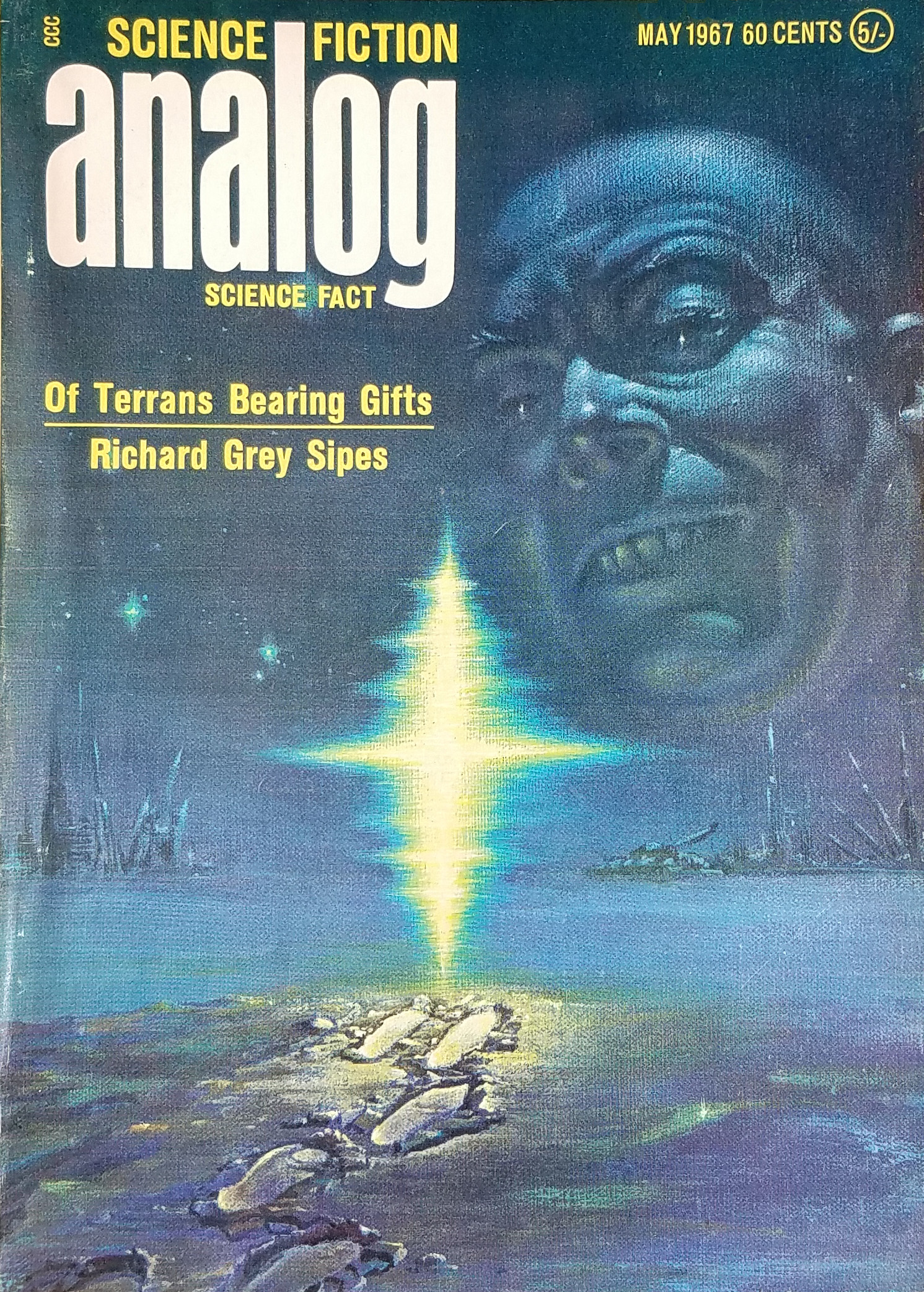

The latest issue of Analog isn't bad, per se. It's just more of the same. I suppose it's a winning formula to keep doing what works, but I expect a little more innovation from my scientifiction.

by Kelly Freas

Of Terrans Bearing Gifts, by Richard Grey Sipes

Things don't start promisingly. We last saw Mr. Sipes in a truly awful epistolary piece a couple of years back. In his sophomore work, a smug Terran trader, name of Winslow, arrives at planet Nr. 126-24 Wilson Two, UTCC, and proceeds to turn things upside down. His store for sale includes a teleporter, an instant translator, a nuclear nullifier, a matter duplicator, and much more.

It's all really smug, which I suppose it's possible to be when you're wielding Godlike power. Winslow justifies his toppling of Wilson Two's society by noting less scrupulous folks will show up sooner or later and do the same thing. It still doesn't make the story fun reading.

Two stars.

Experts in the Field, by Christopher Anvil

by Kelly Freas

Terran linguists assigned to the planet Marshak III are convinced that the indigenous apex animals are sapient, language-using beings. But since they can't decipher the language they use, an interstellar rest stop construction concern is going to come in, claim the planet, and pave over the preferred lands of the aborigines.

It's up to Lieutenant Commander Andrew Doyle to solve the linguist riddle and save the day.

For a Chris Anvil story, particularly one appearing in Analog, it's not bad. Sure, it begins with "[Rank] [Man Name] strode onto the scene…" like virtually every other Anvil story. Yes, the ending paragraphs seem custom made to tickle editor Campbell's fancy (and guarantee a sale). But I liked the puzzle, and it was reasonably well written.

Three stars.

Burden of Proof, by Bob Shaw

by Kelly Freas

There's one ray of bright light in this issue, if I may be indulged the pun. Scottish author Bob Shaw offers up a sequel of sorts to his promising story, Light of Other Days. In this one, he explores the criminological effects of his "slow glass", a substance that rebroadcasts all of the light received from a certain time over that length of time. It is the perfect impartial eyewitness to any crime–provided one is willing to wait long enough to get it (a "ten year" pane might well not disgorge its evidence for a decade, and no speed-ups possible).

This particular tale is told from the viewpoint of a judge, who sent a man to the chair for murder…on circumstantial evidence. What if the eyewitness pane of slowglass, due to show the actual scene ten years after, says something contrary? Is it a miscarriage of justice? Can justice wait a decade?

I particularly liked this tale for questions it raises. It might not be slow glass, but certainly some other technology will arise in the future, like a perfect polygraph or enhancements in fingerprinting, may cause old evidence to be superseded. Does justice wait for these improvements? Can it? And how irrevocable is a decision made on an imperfect data set?

Shaw still is a little clunky in incorporating the explanations of his technologies. Nevertheless, he has a deft, romantic touch to his writing, sorely needed in his magazine. I'm glad Campbell found him. Four stars.

Target: Language, by Lawrence A. Perkins

Mr. Perkins discusses the differences between a variety of languages, and the commonality that may underlie them all. I don't buy his idea that humans develop an internal language that they then translate/adapt to the local vernacular, but it is clear that our species instinctively picks up language at an early age, and what it doesn't learn, it creates on the fly.

If nothing else, it's one of the most readable pieces I've yet encountered in Analog, and on a subject quite interesting to me (and I can verify much of what he says, having studied Russian, Spanish, Japanese, and Hebrew).

Four stars.

Dead End, by Mike Hodous

by Kelly Freas

Did you ever read The Man Who Never Was? It's the engaging true tale of how the British hoodwinked the Nazis into thinking the Allied invasion would go through Sardinia rather than Sicily. It involved seeding a corpse, dressed in a Major's uniform and handcuffed to a briefcase full of forged documents, off the coast of Spain. He was picked up, turned over to German agents, and the story was swallowed, hook, line, and sinker.

Dead End involves a Terran spaceship disabled by belligerent aliens, the capture and investigation of which is certain to give them the secret to our faster-than-light. Or lead them down a blind technological alley…

It's an eminently forgettable story, not helped by the aliens being human in all but name (and extra pair of legs), and the humans being smug in the Campbellian tradition.

Two stars.

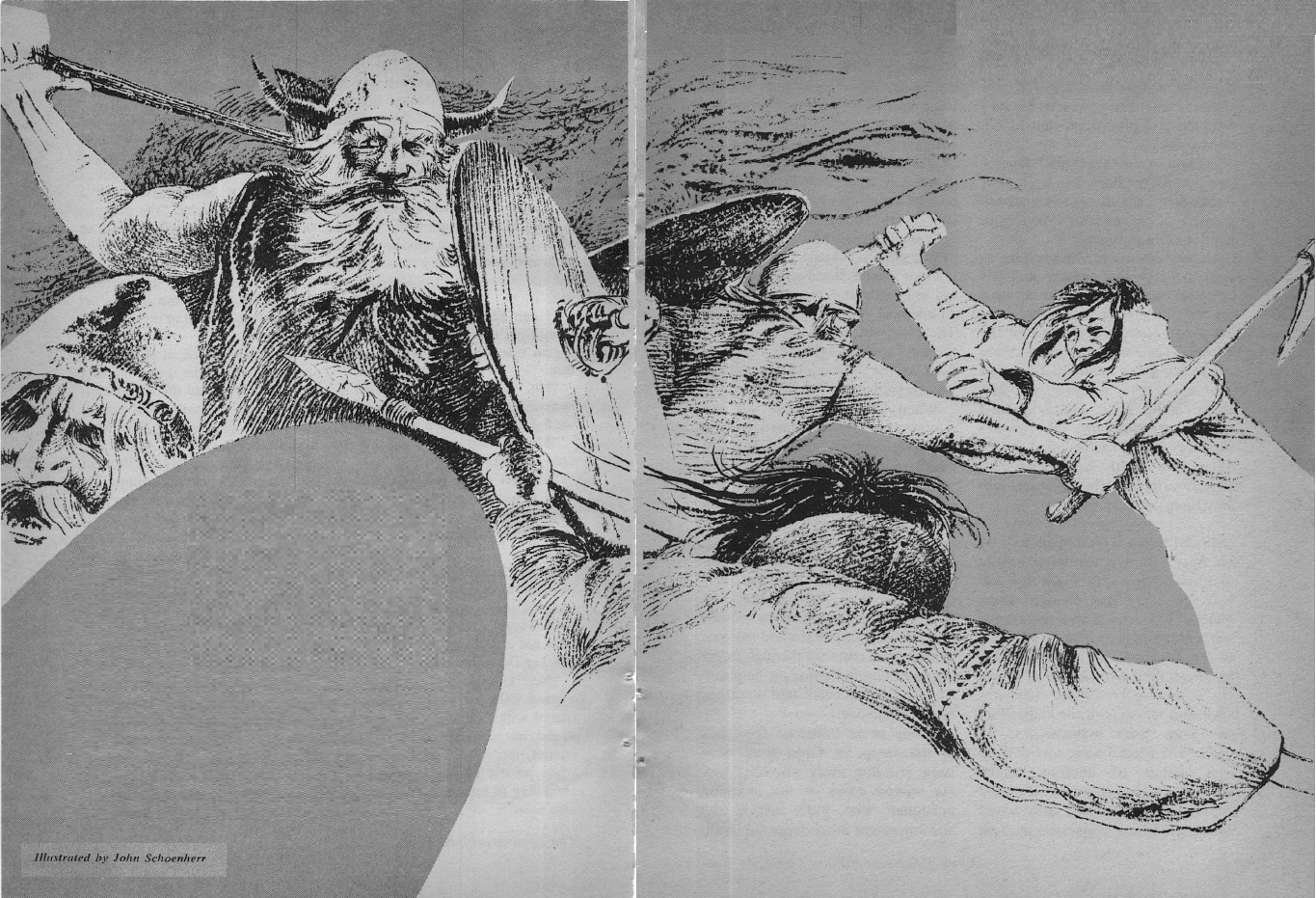

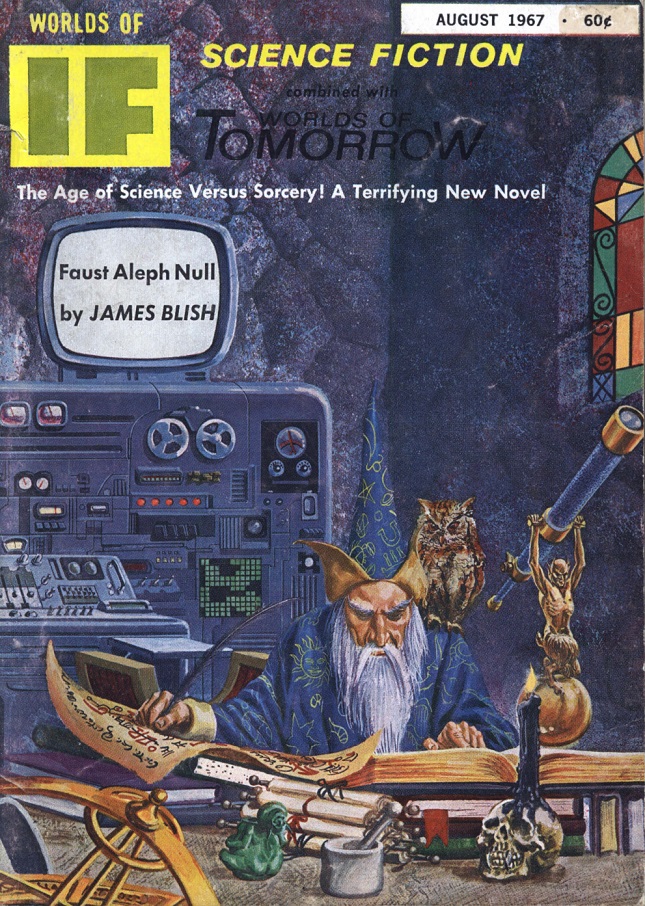

The Time-Machined Saga (Part 3 of 3), by Harry Harrison

by Kelly Freas

At last, the exploits of Barney Henderson, movie producer extraordinaire, come to a close. As expected, the only reason there is archaeological evidence of a Viking settlement in Vinland is because Climax Productions made a movie starring Vikings in Vinland. The whole thing is a circle with no beginning and no end.

It's a compelling thought, further exemplified by a piece of paper that switches hands endlessly between two iterations of Barney. When did it start? Who initially drew the diagram on the paper? Of course, unsaid is the fact that, after endless passings back and forth, the paper should disintegrate…

If the first installment was a bit too silly and the second rather engaging, this third one feels perfunctory. Harrison tells us how the film got done, but the whole thing is workmanlike. Not bad, just a bit sterile. Also, given then carnage involved in the making of the film, I would have preferred a more farcical tone or a more serious one. The middle-of-the-road path makes light of the horror of first contact and the bloodshed that stemmed therefrom, and it taints the whole story.

So, three stars for this segment and three and a half for the book as a whole.

Summing Up

What a lackluster month this was! The outstanding stuff would barely fit a slim volume of a single digest. Analog garnered a sad (2.9) stars. It is only beaten by Fantasy and Science Fiction (3), and it very slightly edges out IF (2.9) and Fantastic (2.9)–they rounded up to 2.9, while Analog rounded down. The last issue of Worlds of Tomorrow (2.4) is left in the dust. We won't have WoT to kick around anymore…

Women wrote 7.41% of the new fiction this month–dismal, but par for the course. On the other hand, we've got a new star in the screenwriting heavens in the form of Star Trek's D.C. Fontana. Perhaps TV is where the new crop of STF women will grow.

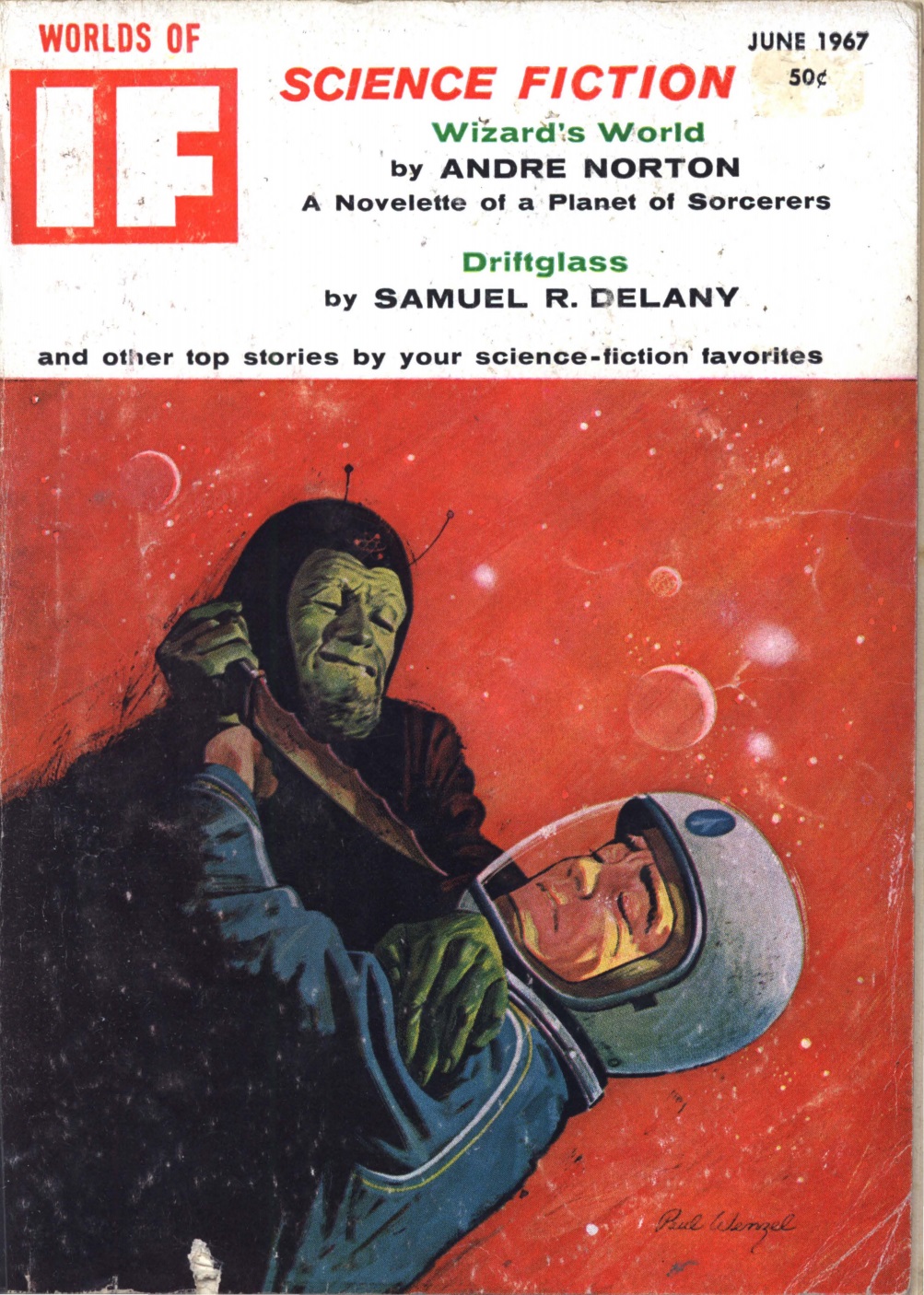

In any event, I've already gotten a sneak preview of next month's IF. We have a stunning new Delany to look forward to. Stay tuned!

The logo for the traffic changeover.

The logo for the traffic changeover. This photo was staged several months ago as part of the education campaign. The real thing was much less chaotic.

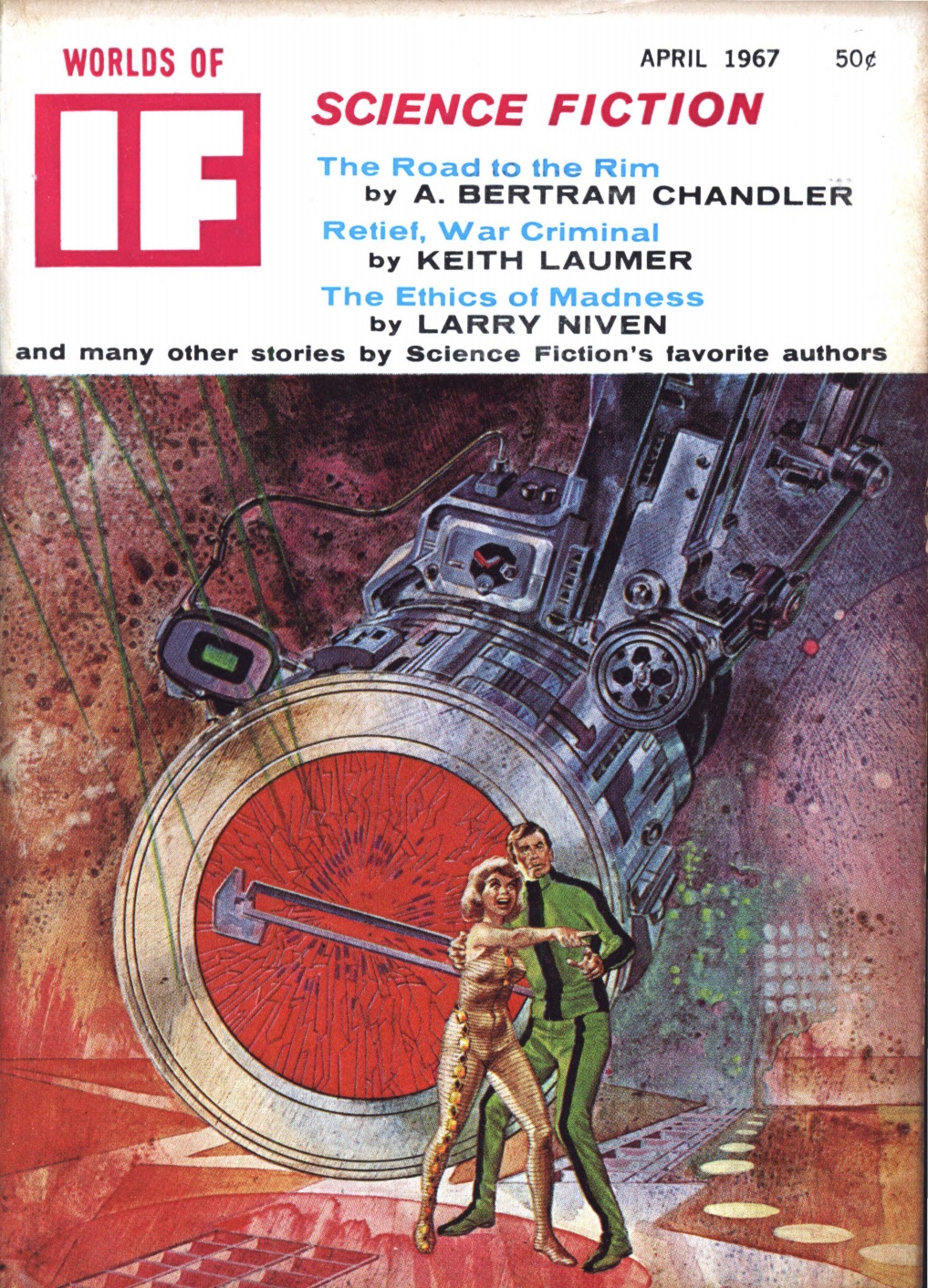

This photo was staged several months ago as part of the education campaign. The real thing was much less chaotic. A newcomer gets the cover. Does he deserve it? Art by Vaughn Bodé

A newcomer gets the cover. Does he deserve it? Art by Vaughn Bodé

![[October 2, 1967] Switching Sides (November 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/IF-1967-11-Cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 2, 1967] Of Genies and Bottles (October 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IF-Cover-1967-10-672x372.jpg)

William C. Foster, the chief American representative to the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament.

William C. Foster, the chief American representative to the Eighteen Nation Committee on Disarmament. The art is intriguing, but none of this happens in Hal Clement’s new novel. Art by Castellon

The art is intriguing, but none of this happens in Hal Clement’s new novel. Art by Castellon![[August 2, 1967] The Bounds of Good Taste (September 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/IF-Cover-1967-09-672x372.jpg)

President de Gaulle with foot firmly in mouth.

President de Gaulle with foot firmly in mouth. This alien dude ranch has become a popular honeymoon spot. Art by Gray Morrow

This alien dude ranch has become a popular honeymoon spot. Art by Gray Morrow![[July 4, 1967] Angels and Demons (August 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/IF-1967-08-Cover-645x372.jpg)

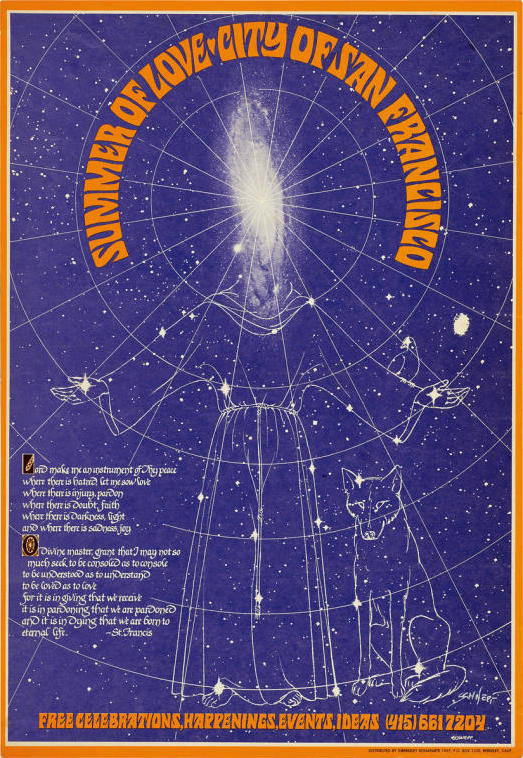

The official poster created by Bob Schnepf

The official poster created by Bob Schnepf The festival was delayed one week due to bad weather.

The festival was delayed one week due to bad weather. This poster is a good example of the new psychedelic art style.

This poster is a good example of the new psychedelic art style. Hippie Randall DeLeon greets the sun and makes the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle.

Hippie Randall DeLeon greets the sun and makes the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle. That’s not quite how black magic works in the new Blish novel, but it ought to be. Art by Morrow

That’s not quite how black magic works in the new Blish novel, but it ought to be. Art by Morrow![[June 2, 1967] Uneasy Alliances (July 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/IF-Cover-1967-07-672x372.jpg)

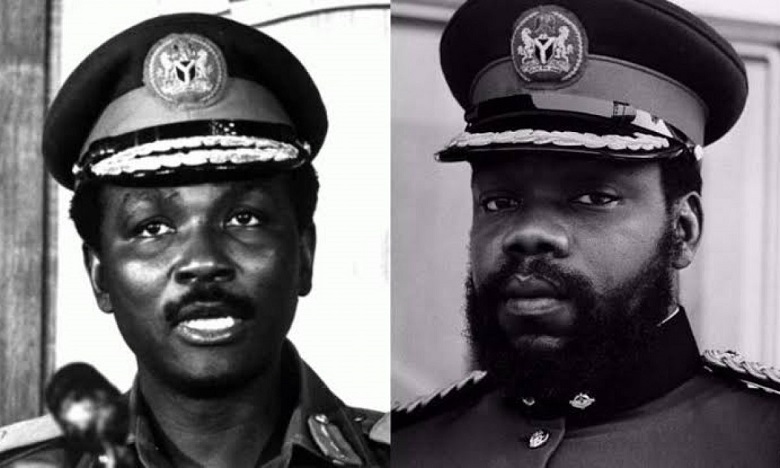

l.: Colonel Yakubu Gowon of Nigeria. r.: Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu of Biafra.

l.: Colonel Yakubu Gowon of Nigeria. r.: Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu of Biafra.  Joe Miller is the most fearsome warrior these vikings have ever seen. Art by Gaughan

Joe Miller is the most fearsome warrior these vikings have ever seen. Art by Gaughan![[May 2, 1967] The Call of Duty (June 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/IF-Cover-1967-06-672x372.jpg)

Muhammad Ali is escorted from the induction center in Houston, Texas.

Muhammad Ali is escorted from the induction center in Houston, Texas.  Uncle Martin and Tim (from My Favorite Martian) seem to have had a falling out. Actually, this is supposedly from Spaceman!

Uncle Martin and Tim (from My Favorite Martian) seem to have had a falling out. Actually, this is supposedly from Spaceman!![[April 30, 1967] Strange New Worlds and Staid Old Ones (May 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/670430cover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 4, 1967] Transitions (May 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/IF-Cover-1967-05-672x372.jpg)

What are these robots up to? Art by Gaughan

What are these robots up to? Art by Gaughan![[March 4, 1967] Mediocrities (April 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/IF-Cover-1967-03-672x372.jpg)

![[February 4, 1967] The Sweet (?) New Style (March 1967 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IF-Cover-1967-02-full-672x372.jpg)