By Ashley R. Pollard

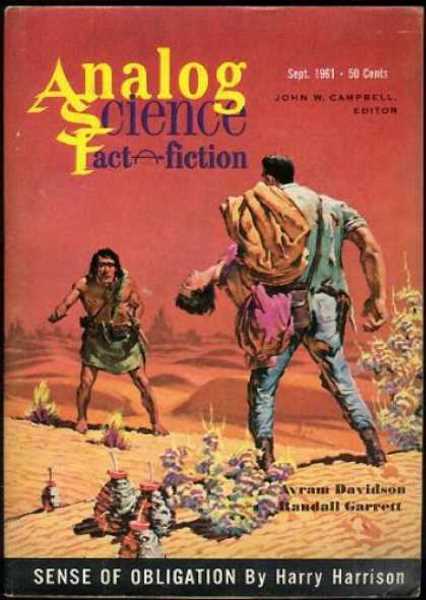

August may have started with cool weather but it ended with a bit of heat wave for the August Bank Holiday weekend. So I did get to sit on the beach eating ice-cream and reading a good book, and in this case having the pleasure of reading Arthur C. Clarke’s latest A Fall of Moondust, of which John Wyndham has said, “The best book that Arthur C. Clarke has written.” A high praise indeed.

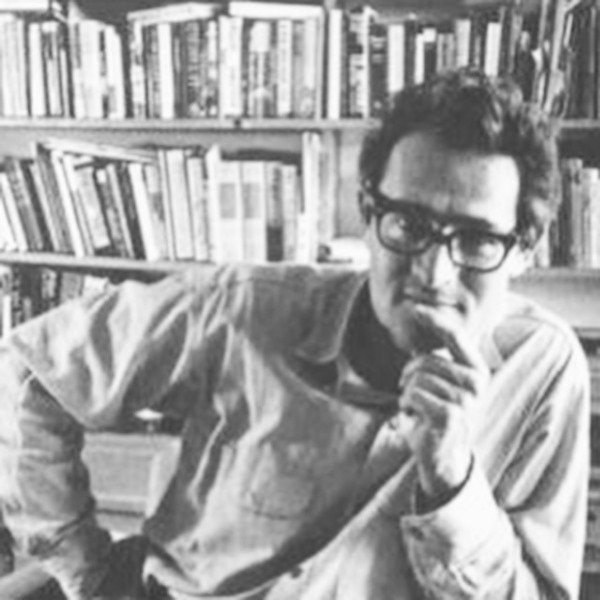

I have been a fan of Arthur’s work after reading his novella, which first appeared in Startling Stories, called Against the Fall of Night. I’ve also been fortunate to have had the pleasure of meeting him. For those of you who follow my writing here I can also recommend, if you want a taste of the man’s humour, his short story collection Tales from the White Hart. The title of which is play on the name of the original pub that The London Circle used to frequent.

Arthur C. Clarke’s latest book probably cements his reputation as one of the key science fiction authors of our age; the others being Isaac Asimov and Robert A. Heinlein. His breakout novel, if you will indulge me in describing it as such, was arguably Childhood's End, which was released in 1953. It describes the arrival of the Overlords on Earth to guide humanity and ends with the transcendence of mankind into something more than human. This was followed by my favourite novel of his The Deep Range in 1957, which tells how a former astronaut becomes an aquanaut, and describes the adventures arising from farming the sea.

So the question is, does A Fall of Moondust live up to John Wyndham’s effusive praise?

The story starts with Captain Pat Harris describing the passengers boarding the Moon’s first cruise ship. It is the Selene, run by The Lunar Tourist Commission, which sails the Sea of Thirst: a sea made of superfine dust that a vessel can float on. Clarke manages to effectively evoke the other-worldliness of the moon, while at the same time setting a scene that could be have taken place on any cruise ship on Earth, with a largely mundane set of tourists. The setting roots the fantastical elements into something familiar, making the adventure that follows extremely plausible, of when a holiday of a lifetime turns into a disaster.

Clarke intertwines the unfolding of the voyage with snippets of the world that the people come from and the development of his future society’s technology, including fusion and solar power. Overall, the world of Moondust is optimistic about the future of mankind, almost cosy — up to the point when disaster strikes.

The catastrophe is a moon quake. It creates a whirlpool that envelopes the Selene beneath 15 metres of dust. But this is no story of hysteria, rather it is one of courage in the face of adversity, driven by the underlying belief that problems can be solved.

The story is effectively told from various viewpoints. The story opens describing the voyage of the crew and passengers of the Selene. After the disaster we are then taken to the viewpoint of the people searching for the lost ship, who have to come up with a way of getting everyone off safely. Clarke masterfully describes the problems on both sides, and the various solutions that are undertaken as the clock counts down toward eventual doom — when everyone aboard the Selene will die from lack of oxygen.

Everything is cooly set-up, but then Clarke defies the readers' expectations, piling problem on top of problem. The experience is intense, as one wonders what will happen next. But Clarke manages to keep racking up the tension, teasing the reader with solution only to reveal that there is more going wrong from unintended side-effects. For example, leaking water from the Selene’s water tanks seeps into the dust and unbalances the ship, which further hinders the rescue operations.

Technology may well enable fantastic things like cruises across the dust seas of the Moon, but it is not omnipotent; you cannot defy the laws of physics, and the exploration of this distinction is where the novel excels. The characters agency is constrained by what is possible, and in this way the story reminds me of The Cold Equations by Tom Godwin, except that Moondust is no maudlin tale of the consequence of stupidity, but rather a paean to reason and engineering.

So is this the best story that Arthur C. Clarke has written? My answer is probably not, but there again Childhood's End and Deep Range are hard acts to follow. Moondust is a tour de force he delivers here, an excellent SF suspense-thriller. The story drew me in and I sat and read it in a single day. I imagine you will, too, some fine late summer day.