by Gideon Marcus

The coverage for John Glenn's orbital flight was virtually non-stop on the 20th. My daughter and I (as many likely did) played hooky to watch it. During the long countdown, the Young Traveler worried that the astronaut might get bored during his wait and commented that NASA might have been kind enough to install a small television on the Mercury control panel.

But, from our previous experience, we were pretty sure what the result of that would have been:

CAPCOM: "T MINUS 30 seconds and counting…"

Glenn: "Al, Mr. Ed just came on. Can we delay the count a little bit?"

30 minutes later…

CAPCOM: "You are on internal power and the Atlas is Go. Do you copy, Friendship 7"

Glenn: "Al, Supercar's on now. Just a little more."

30 minutes later…

CAPCOM: "The recovery fleet is standing by and will have to refuel if we don't launch soon…John, what's with the whistling?"

Glenn: "But Al, Andy Griffith just came on!"

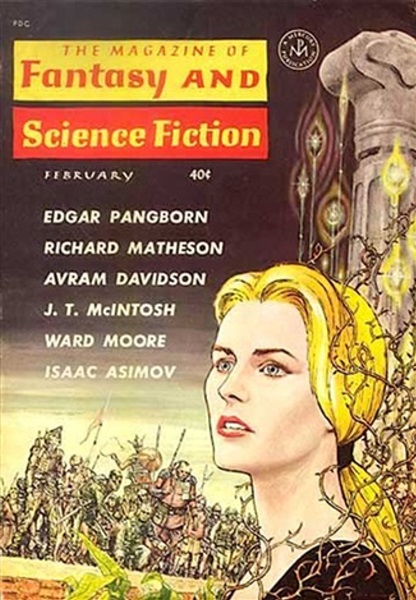

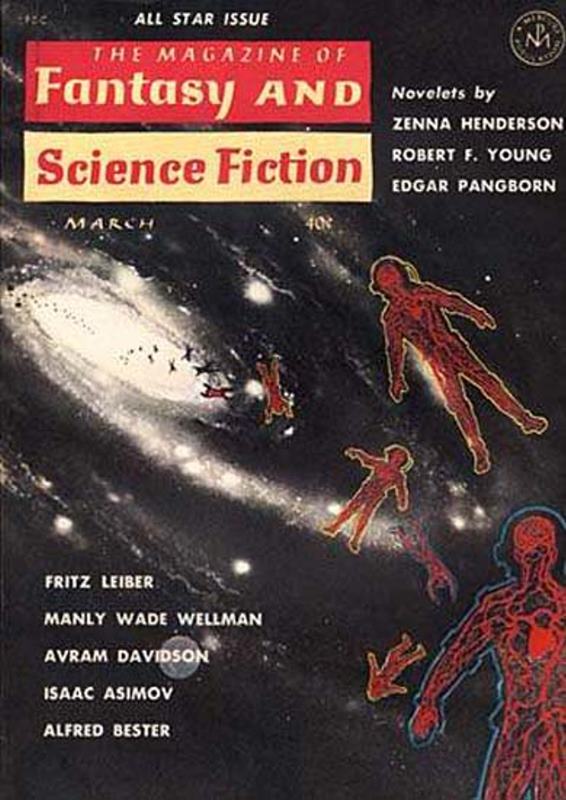

So, TV is probably out. But a good book, well…that couldn't hurt anything, right? And this month's Fantasy and Science Fiction was a quite good book, indeed. Witness:

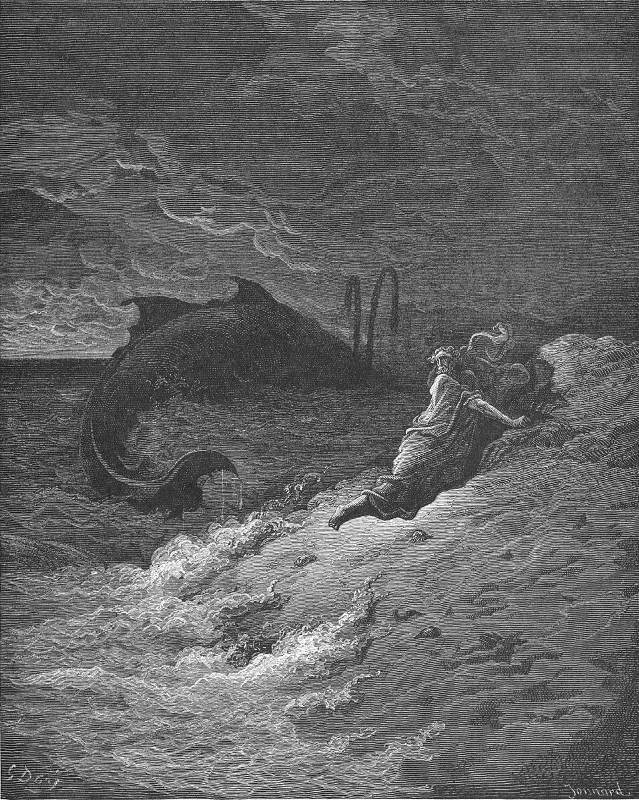

Jonathan and the Space Whale, by Robert F. Young

Two years ago, Mr. Young began an issue of F&SF with a bang. He does it again with Whale. Young is a master of writing compelling relationships between two utterly alien beings – in this case, that between a restless, aimless young man of many talents, and the space whale that swallows him whole. Great stuff. Five stars.

Wonder as I Wander: Some Footprints on John's Trail Through Magic Mountains, Manly Wade Wellman

It is hard to pack a lot of wallop into a half-page vignette, but I must say that Wellman has pulled it off here – repeatedly. Footprints is a set of short-short shorts designed to be interstitials for a collection (due to be published later this year) of stories about John the balladeer, a Korea veteran with a silver-stringed guitar and a facility with white magic. Some are truly effective, and all are worthy. Five stars.

The Man Who Made Friends with Electricity, by Fritz Leiber

Friends is a readable story with a stingless tail. I suspect Leiber is past his prime, riding on his name rather than putting much effort into things. Three stars.

Through Time and Space with Ferdinand Feghoot: XLIX, by "Grendel Briarton"

One of the more contrived and less funny of Reginald Bretnor's punnish efforts.

A War of No Consequence, by Edgar Pangborn

This, then, is the jewel of the issue. Pangborn's last tale of a young redheaded runaway from the Eastern seaboard of a bombed-out America, was sublime. This one is just about as good, only being inferior for its shorter length. A great story of the futility of war, and the bonds it can forge among ostensible enemies. Five stars.

The 63rd St. Station, by Avram Davidson

I'm not quite sure what to make of this one, about a staid, devoted brother who contemplates leaving his shut-in sister for a new love at the age of 45. The ending is rendered extremely obliquely, and I suspect it makes more sense to a New Yorker familiar with subway trains and such. Not bad, but a little too opaque. Three stars.

(Per the editor's blurb at the front of the issue, Bob Mills is stepping down as editor and turning over the reins to Mr. Davidson. Given the latter's penchant for the weird and the abstruse, recently to the detriment of his stories (in my humble opinion), I have to wonder if this will take the magazine in a direction less to my taste. I guess I'll have to wait and see.)

Communication by Walter H. Kerr

There is not much to say about this rather purple, but still pleasant, poem about a certain race's limitations and strengths in the realm of communication. Three stars.

That's Life!, by Isaac Asimov

The Good Doctor (will the friendly banter between Asimov and his "Kindly Editor" continue under the new regime?) has turned out an entertaining and informative piece this month, in which he attempts to present an accurate definition of life. It's a fine lesson in biology with some neat bits on viruses. Four stars.

The Stone Woman by Doris Pitkin Buck

I really want to like Mrs. Buck, an esteemed English professor from Ohio, who has seen several science fiction luminaries in her class. This latest piece, a poem, reinforces my opinion that her stuff, while articulate, is not for me. Two stars.

Shadow on the Moon by Zenna Henderson

Henderson's The People stories have always been personal favorites, and the last one, Jordan, was sublime. Shadow, on the other hand, falls unexpectedly flat. It follows the tale of two siblings who enlist themselves in an endeavor to take themselves and kin back into space – to the Moon, particularly. All the elements of a People piece are there: the esper-empowered, alien-born humans; a well-drawn female protagonist; the sere beauty of Arizona; the light, almost ethereal language. Somehow, the bolts show on this one, however, and there isn't the emotional connection I've enjoyed in previous Henderson stories. Three stars.

Doing my monthly mathematics, I determine that the March F&SF garnered an impressive 3.8 stars. Astronaut Glenn certainly could have whiled away the long pre-launch hours (not to mention all the previous scrubbed launches) with a lot worse reading material.

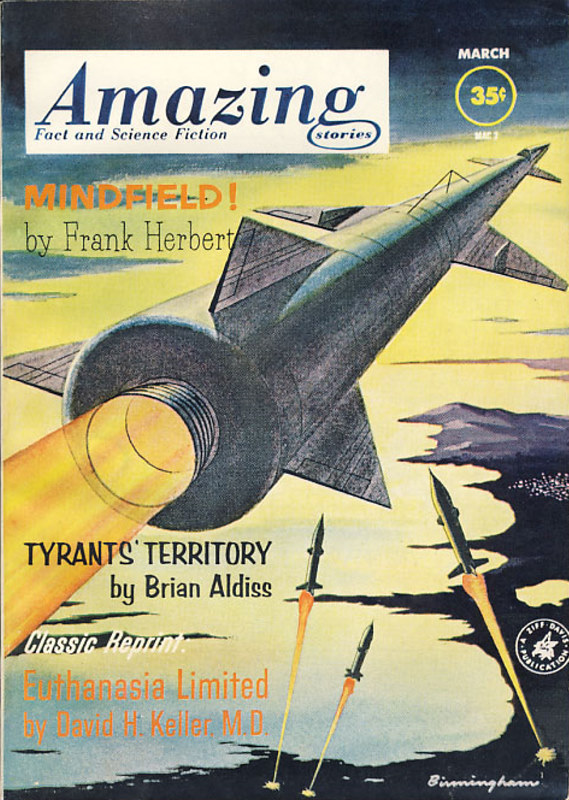

Next up…what's likely to be worse reading material (but who knows?): the March 1962 Analog!