by John Boston

Science fiction becomes science fact! Well not quite, fortunately for us all. It appears that we came to the brink of nuclear war last month but our leaders on both sides had sense enough to turn back from it. These grave events reverberated even here, far from any population center or promising military target. We were herded to a school assembly to be addressed by the principal, very briefly. It went more or less like this:

“We, ah, don’t think . . . er, anything . . . is going to . . . ah, happen, but if, er, . . . something . . . ah, happens . . . classes will be dismissed and you will return to your homes” (these last clauses delivered with accelerating confidence, unlike the earlier ones).

Shortly thereafter, I was outside in gym class (physical education, as they call it here). In a corner of the large outdoor area, the school’s paper trash was burning in a concrete enclosure. (Isn’t there a better way of disposing of this stuff than burning it in the open air? There ought to be a law.) The wind shifted, and fine bits of ash began drifting down on us. “Fallout!” someone yelled.

So much for existential terror, at least in the so-called real world. There’s a fair dose of it in the December Amazing, however, and this issue is noticeably wider awake than its recent predecessors.

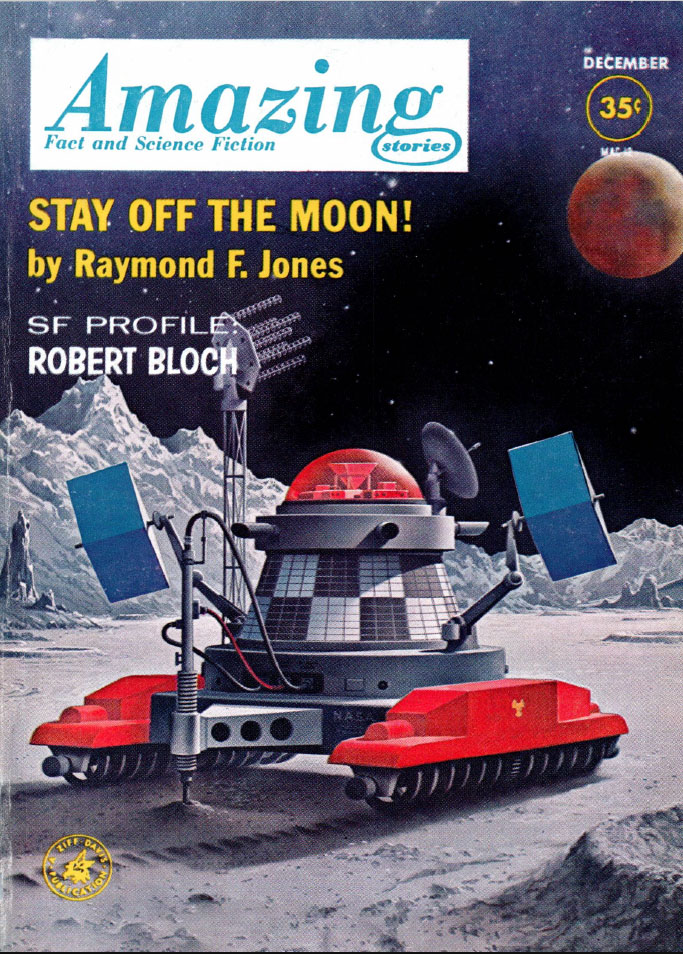

Raymond F. Jones contributes the lead story Stay Off the Moon! Jones is an intermittently prolific 20-year veteran who has produced a lot of cut-to-specs product but sometimes comes up with clever oddball ideas, and here’s one of them. Our guys at Mission Control succeed in putting a remote-controlled mobile laboratory device on the Moon to take soil (i.e. rock) samples, analyze them, and transmit the results. Turns out the atomic weights and energy levels are different from the matter we know. How can that be? The Moon must have originated a long, long way away, in a place where the laws we thought are universal don’t quite work. Well, what else is going on up there? Finding the bizarre but logical (and terrifying) answer is the rest of the story. This is the kind of thing only an SF fanatic can appreciate, but within those bounds it’s imaginative and well done. Four stars.

Roger Zelazny’s Moonless in Byzantium—his second Amazing story, fourth published—might have a broader appeal. It’s a surreal riff on one of the more familiar plots in the warehouse, the lone rebel face to face with an oppressive regime, in this case the Robotic Overseeing Unit. In this dystopia, machines are in charge, people are mostly machines, and our protagonist is charged with writing Sailing to Byzantium on a washroom wall. He is also charged with illegal possession of a name—William Butler Yeats, which he appended to Yeats’s poem. This is the world of Cutgab, in which language itself is drastically restricted and simplified, and writing forbidden. ROU accuses: “You write without purpose or utility, which is why writing itself has been abolished—men always lie when they write or speak.” The outcome is inevitable save for the accused’s final and futile defiance. This is one that succeeds on sheer power of writing; in theme and style, it suggests Bradbury with sharper teeth. Four stars for bravura execution of a stock idea.

This month’s Editorial indicates that some readers thought that this Roger Zelazny was himself a fictional character, and prints Zelazny’s reassurance that he exists; his Polish ancestors were armorers and the name comes from the Polish for “iron”; he’s 25, and possesses an M.A. in English and Comparative Literature from Columbia University, military training as a guided missile launcher crewman, and his old copies of Captain Future.

The Zelazny is followed by Far Enough to Touch, by Stephen Bartholomew, who had a couple of stories in If and one in Astounding a few years ago. A space mission is returning from the Moon, and suddenly one of the crew—the young one who seemed most entranced by space—has gone out the airlock in his spacesuit. Rescued, he’s in an ecstatic delusional fugue, and stays that way. And the point? It escapes me, but the story is very smoothly written. Two stars.

Stewart Pierce Brown contributes an equally well-turned but insubstantial story in Small Voice, Big Man, in which the voice of a washed-up singer suddenly is emanating from radios everywhere, to benign effect. And the singer, Van Richie, is trying to make a comeback, but had a hard time singing loudly enough until the producer’s electrician rigged up an amplifier for him to wear. OK, clear enough, but so what? Two insipid stars—but this one is also smoothly written, not surprisingly from a writer who’s been in Bluebook, Collier’s, Playboy, and the Saturday Evening Post.

Marion Zimmer Bradley, who served up a dish of broken glass in the last issue, is back with something more soothing. Measureless to Man takes place on yesterday’s Mars, where explorers travel on foot through the mountains with tents and sleeping bags, people get around by flagging down the mail jet, and the fauna include cute scaly sand mice and banshees, giant, stupid but dangerous flightless birds. I suspect that this story was at least started a decade ago in hopes of a sale to the now-deceased pulps that Bradley admired. Anyway, it concerns an expedition into the said mountains to the ancient city Xanadu, abandoned ages ago by the seemingly extinct Martians, from which no previous expedition has returned, and you can more or less guess what happens, in broad outline at least. This used furniture is rearranged agreeably enough, with a slightly ironic, newer-style ending. Three stars.

Sam Moskowitz’s “SF Profile” this issue is “Psycho”-logical Bloch, which is a little puzzling; Moskowitz readily concedes that Robert Bloch is a fairly inconsequential SF writer and that his main credentials are in horror and psychological suspense, at this point chiefly in film and TV. Apparently Bloch is here in this series featuring the likes of Asimov and Heinlein because he’s popular among fandom. But for a relatively pointless article, it’s perfectly readable and informative. Three stars.

Finally, Frank Tinsley is back with The Mars Supply Fleet, doing his best to make space travel pedestrian again. Two stars for making interesting information boring.

But still, cause for hope: two items in this issue poke their heads above the cloudbank of routine, in very different ways…

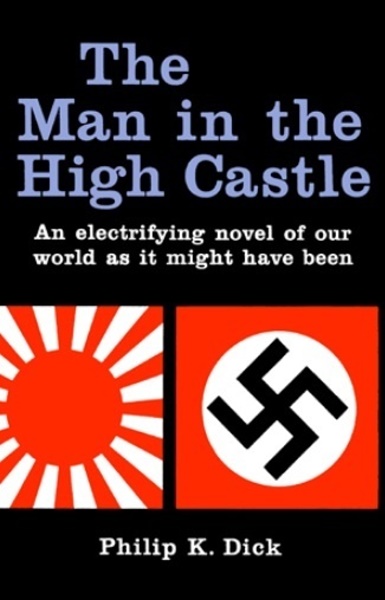

![[November 6, 1962] The road not taken… (Philip K. Dick's <i>The Man in the High Castle</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/book2-672x372.jpg)