[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Mark Yon

I hope you’ve all had a good Christmas. Here in Britain it has been…. interesting. As fellow traveller Ashley has mentioned, the cold and foggy weather has now turned into a fully-fledged Winter of ice and snow. As I type this, snow has been falling all over the UK in great amounts for a couple of weeks, and is showing no sign of stopping. The result has been chaos. The news is filled of stories about villages being made inaccessible and even in the urban areas, such as the Northern provincial city I live in, travel has been treacherous. The Met Office is telling us that it is “The Big Freeze”, and may be the worst winter weather in decades. Even if it is not, it certainly feels like it!

Anyway, enough of the weather.

As I said I would, I have braved the Winter cold to go to the cinema since we last spoke, and I am pleased to say that I whole-heartedly recommend Mr. David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, despite its length. I saw the movie in two parts, with an intermission. At a run-time of just under four hours I was not bored for one moment. It is one of the best-looking movies I have ever seen, and I loved the majestic score by Mr. Maurice Jarre, so much so that I am now looking for a copy of the movie soundtrack to play on my record player. As it is mainly set in the desert, though, it might just be what’s needed to keep the Winter chill out!

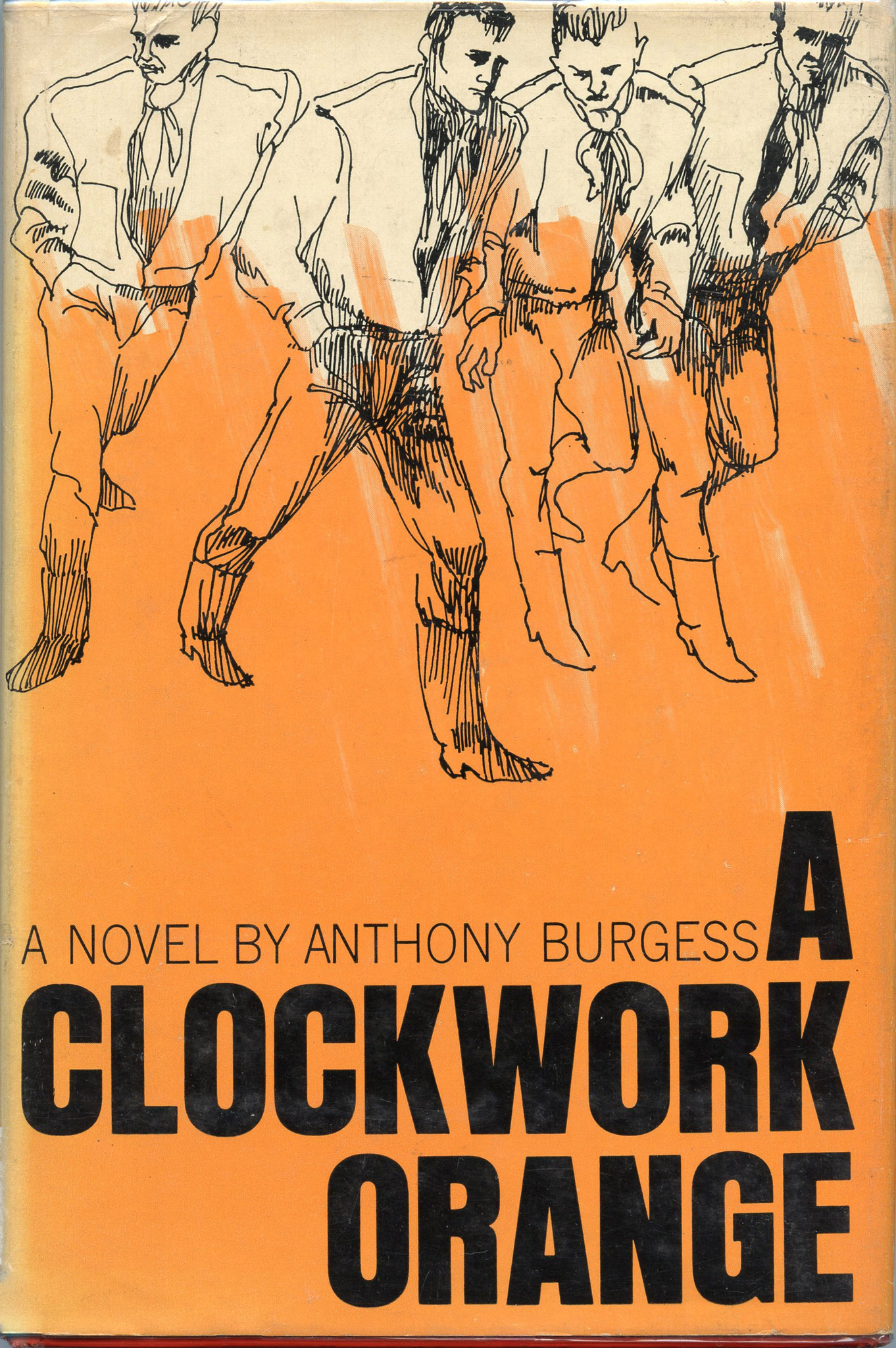

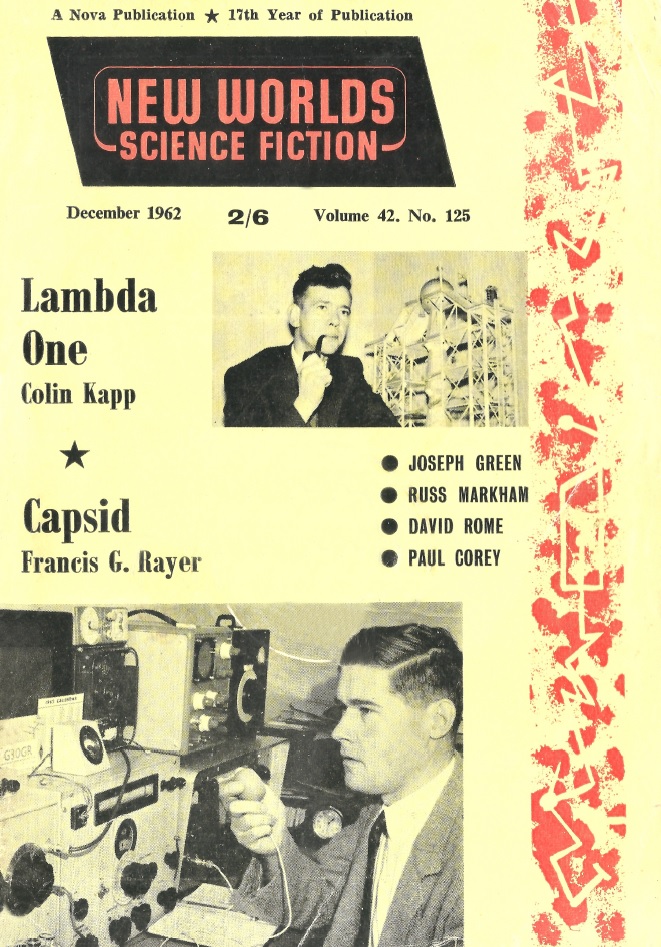

This month’s New Worlds shows a cover that’s back to the lurid. This month, it is an unsubtle Day-Glo shade of Santa Claus red. It heralds the return of a story by Mr Lan Wright after his stint as guest Editor last month. This is the first time that Mr. Wright has had an actual story in the magazine since February 1959. It is the first of three parts. More on this later.

I Like It Here, by Mr. David Rome

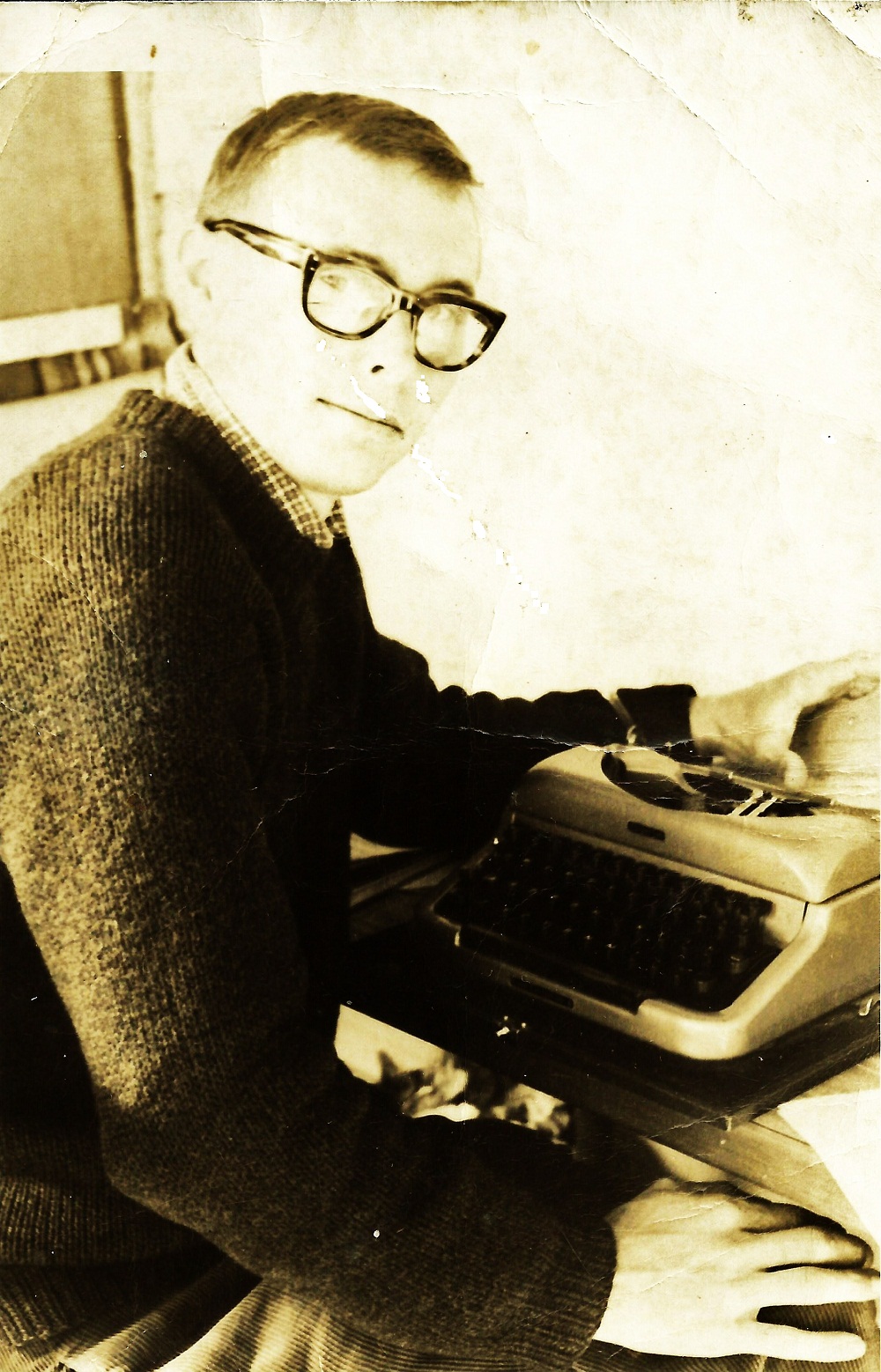

We begin with a short guest editorial from Mr. Rome – his fourth appearance in New Worlds in as many consecutive months, which suggests that he is a popular choice, by the editors, and (one hopes) the reading public. [David is also quite popular with the Journey, having recently engaged in written correspondence with us. It is he who provided the picture above. (Ed.)]

Mr Rome is a relative newcomer to s-f and as a result has a rather refreshing viewpoint upon professionalism in the genre here. It is the latest foray into the ongoing battle between the prevalent issue in British s-f – should it be populist entertainment but written by amateurs, or more specialist and challenging, with professional leanings? Mr. Rome’s take on it is that, as a relative newcomer, the s-f writer is motivated by a belief in the genre rather than by money. As a result, an acceptance of s-f by the mainstream, in his opinion, would lead to dissolution and a loss of the thing that makes s-f great. It’s an intriguing point of view, rather similar to that anti-professional stance given by Mr. Wright as editor last month.

Which leads us to:

Dawn’s Left Hand, by Mr Lan Wright.

The title’s a good one (a quote from the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam) but despite such lofty ambitions, the actual story shows its amateur origins by being rather uneven in tone and pace. I must admit that I was rather disappointed by the story. The plot is admittedly fast-paced, in an old-fashioned pulp style, but like many of the old-style stories of the Golden Age, if you actually stop to think about it, the plot has no logic. It is entertaining, but really doesn’t hold much water. As expected, the story ends on a cliff-hanger, to be continued next issue. I hope that it improves. Two out of five.

Ecdysiac, by Mr. Robert Presslie

This story marks the return of another regular New Worlds writer. His last was Lucky Dog in the November 1962 issue, which I thought was disappointing. This was better, an espionage tale that adopts the use of psionics in ways that I imagine Mr. Poul Anderson and Mr. A. E. van Vogt would. The dour ending is typically British, though! Three out of five.

The Big Tin God, by Mr. Philip E. High

Another regular New Worlds writer, last read with The Method in the November 1962 issue, which I was not enormously impressed by. This one is, thankfully, better. It’s a story of city-states, and a secret war that leads to the creation of an artificial intelligence capable of independent thought. The short story held my attention, although the twist at the end was a little predictable and, if I dare say it, even arrogant in its presumption. Two out of five points.

Burden of Proof, by Mr. David Jay

Mr. Jay gives us a story of hate and murder, placed within a futuristic mystery and a possibly mistaken accusation. It’s nicely done but the denouement depends on a hook that’s not too convincing. Again, two out of five.

The Statue, by Mr. R. W. Mackelworth

After a number of well-known authors, it’s great to have a new one. Mr. Mackelworth’s The Statue is a worthy debut as a short story about a mysterious artefact and its effect on a group of explorers. There’s an interesting use of telepaths in the tale but it is let down by some standard (and rather predictable) stereotypes. Three out of five.

The Subliminal Man, by Mr. J. G. Ballard

Although Mr. Lan Wright has the biggest billing, here is the best story in the magazine, from another initialled author, the much-welcome Mr. J. G. Ballard. We don’t see enough of Mr. Ballard’s work these days in New Worlds, and it is noticeable how good it is when compared with the rest. It is also miles away from the traditional s-f that we expect. A dystopian tale of the future consequences of incessant advertising and relentless consumerism, its sense of paranoia is both chilling and effective. Four out of five.

Lastly, there’s the usual Book Review by Mr. Leslie Flood. There is only one recommendation this month albeit a wholehearted one and a collection you already have in the US – A Decade of Fantasy and Science Fiction, edited by Mr. Robert P. Mills.

As recent issues of New Worlds go, this one feels stronger, even if the quality of the stories varies somewhat. The return of Mr. J.G. Ballard raises the bar a little and makes me feel a little more positive for the future of the magazine than I have been lately.

And with that hint of optimism, until next time, it just remains for me to wish you all the best for 1963.

[P.S. If you want the chance to nominate Galactic Journey for Best Fanzine next year, you need to register for WorldCon before the end of the year! (or have registered last year… but then you can only nominate, not vote.) The Journey will be at next year's WorldCon, so don't miss your chance to meet us and please help put us on the ballot for Best Fanzine!]