by Victoria Silverwolf

It's déjà vu all over again. — attributed to Yogi Berra

A couple of months ago the first issue of Worlds of Tomorrow offered half of an enjoyable, if juvenile, novel by Arthur C. Clarke, half a dozen poor-to-fair stories as filler, and one excellent work of literature. The second issue is almost exactly the same, except for the fact that one of the six mediocre stories has been replaced by a mediocre article.

The Star-Sent Knaves, by Keith Laumer

We begin with a madcap farce from the creator of the popular Retief stories. Great works of art disappear from locked rooms, without any signs of tampering. The hero hides inside a vault full of valuable paintings and waits for the thieves to show up. They appear from nowhere, inside a strange device. The protagonist assumes it's a time machine. Thus begins a wild chase, involving criminals, aliens, and humanoids from other dimensions. The pace never lets up, and the story provides moderate amusement. Three stars.

The End of the Search, by Damon Knight

This is a very brief story. In the far future, a man searches for the final specimen of the last species that humanity has wiped out. The plot is somewhat opaque and requires careful reading. Many will be able to predict the story's twist ending, and some will not care for its mannered style. I found it troubling and haunting. Three stars.

Spaceman on a Spree, by Mack Reynolds

A future world government brings peace and prosperity to the planet. A minimum guaranteed income for everyone means that nobody has to work to survive. A system resembling the military draft selects people at random for various jobs, depending on their skills. In return for their labor, they earn a higher income. The protagonist is the only qualified astronaut. (The implication is that the universal welfare system has made humanity less interested in dangerous exploration of the solar system.) When he completes his last mandatory mission, he plans to retire on his savings. In order to keep the space program from dying out, two officials scheme to make him lose all his wealth, so he will have to return to service. They way in which they do this offers no surprises. The ending is something of an unpleasant shock. The author's portrait of a semi-utopian future is interesting. Three stars.

The Prospect of Immortality, by R. C. W. Ettinger

This is an excerpt from a privately printed book. It discusses the possibility of freezing people at the time of death, in the hope that future medical technology will be able to revive them. The concept is a familiar one to readers of science fiction, and the author offers few new insights. Two stars.

A Guest of Ganymede, by C. C. MacApp

Aliens establish a station on Ganymede. In exchange for large amounts of a metal that they require, they will inject a human being with a virus that cures all ailments. They absolutely forbid anyone to take this cure-all outside the station. A criminal takes a blind man to the aliens. While they restore his sight, the crook plots to smuggle the virus to Earth. Things don't work out well. This is a fairly effective, if rather grim, science fiction story. Three stars.

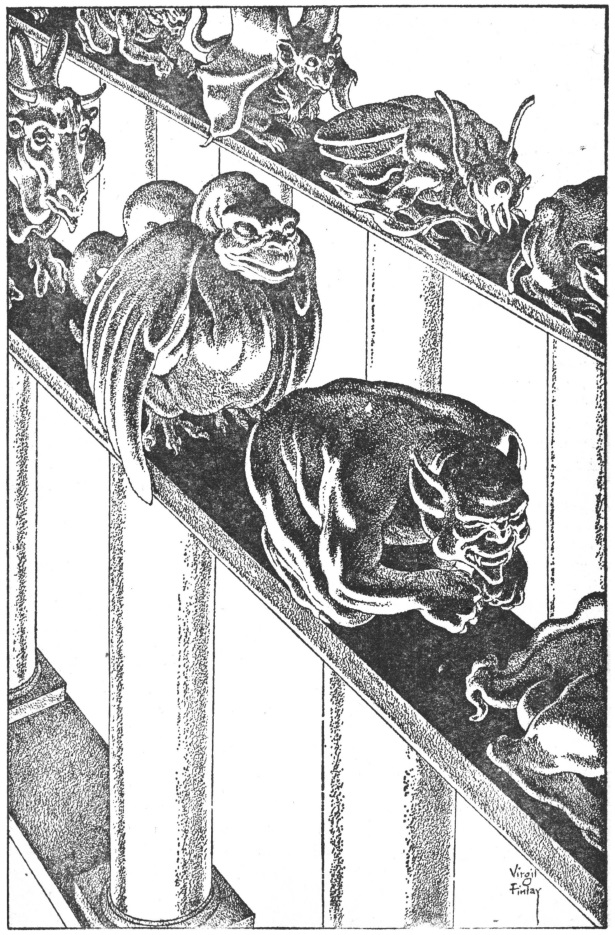

The Totally Rich , by John Brunner

A prolific British author offers a story about immense wealth and its limitations. The narrator is a scientist and inventor who works on a project in a quiet Spanish village. He soon finds out that a woman with virtually limitless resources carefully manipulated him into accepting this position for her own reasons. Even the village is an artificial one, created only to give him a place where he could work without distractions. Richly characterized and elegantly written, this is a compelling tale of love, death, and obsession. It reminds me a bit of the work of J. G. Ballard, although the author's voice is wholly his own. As a bonus, the story features striking illustrations by the great Virgil Finlay. Five stars.

Cakewalk to Gloryanna, by L. J. Stecher, Jr.

A spaceman delivers valuable plants from one planet to another. Multiple complications ensue. I didn't find this comedy very amusing. The detailed ecology of the plants is mildly interesting. Two stars.

People of the Sea (Part 2 of 2), by Arthur C. Clarke

The adventures of our boy hero on a small island near the Great Barrier Reef continue in the conclusion of this short novel. In this installment, his scientist mentor begins experiments to see if killer whales can be convinced to stop eating dolphins. A hurricane strikes the island, destroying its medical supplies and radio equipment. The boy must make a long and dangerous journey across the sea, with the help of two dolphins, in order to save the life of the scientist, who is dying of pneumonia. Although episodic, and with some major themes brought up and never resolved, this is an enjoyable adventure story. Young readers in particular will appreciate the author's clear, readable style. Four stars.

Unlike love, as Bing Crosby reminds us, Worlds of Tomorrow may not be better the second time around, but it's at least as good.