by Mark Yon

[Time is running out to get your Worldcon membership! Register here to be able to vote for the Hugos.]

Snapshot from England

Hello from 1964!

Christmas here was a good one. The weather, though cold, was nothing like last year’s record-breaking Winter, thank goodness.

As rather expected, The Beatles were Number 1 in the charts with I Want to Hold Your Hand. They have dominated British culture this year, and this going straight to the top of the charts here reflects that. There were pre-orders of over one million copies.

I’ve also had chance to catch up with some movies in the cinema. This year’s Christmas movie for the family was It’s A Mad Mad Mad Mad World, which we enjoyed a lot. Very silly, but we enjoyed looking out for all the cameos. We will probably go see Walt Disney’s The Sword in the Stone over the holiday season, which appeared in the cinema on Boxing Day here. Really looking forward to seeing how much of the novel remains.

And so, to genre business. On the magazine front I have to start this month’s report with the sad validation of something I’ve been expecting for a while now. Since we last spoke it has been announced that “due to declining sales” New Worlds and Science Fantasy magazines are to close. It is sad, but not too surprising. I have for a number of months now been commenting on the variable quality of our homegrown content, and it has been clear in a number of ways that things have been difficult, so this is not a complete surprise. According to the news release we definitely have material until the April 1964 issue and then I guess we will see what happens. I am hopeful that this will not be the end of British-based magazines, though. There are rumours of a take-over bid that will allow at least one of the magazines to continue, but nothing is definite. Interesting times!

On a more positive note, the television programme Doctor Who has continued to enthral the household. It has become our family “must-see” on a Saturday teatime. New Traveller Jessica has written about this in detail, so I won’t go into it at great length. Whilst I was less impressed with the caveman story that followed the promising first episode, the latest tale is a science-fictional one which has introduced a metallic monster that Mr. H.G. Wells would have been proud of. The Daleks are quite inhuman and scarily strident in their determination for galactic subjugation. More importantly, they are an enormous success for the BBC. They have clearly struck a chord. I look forward to seeing where this goes.

The Reading Matter at Hand

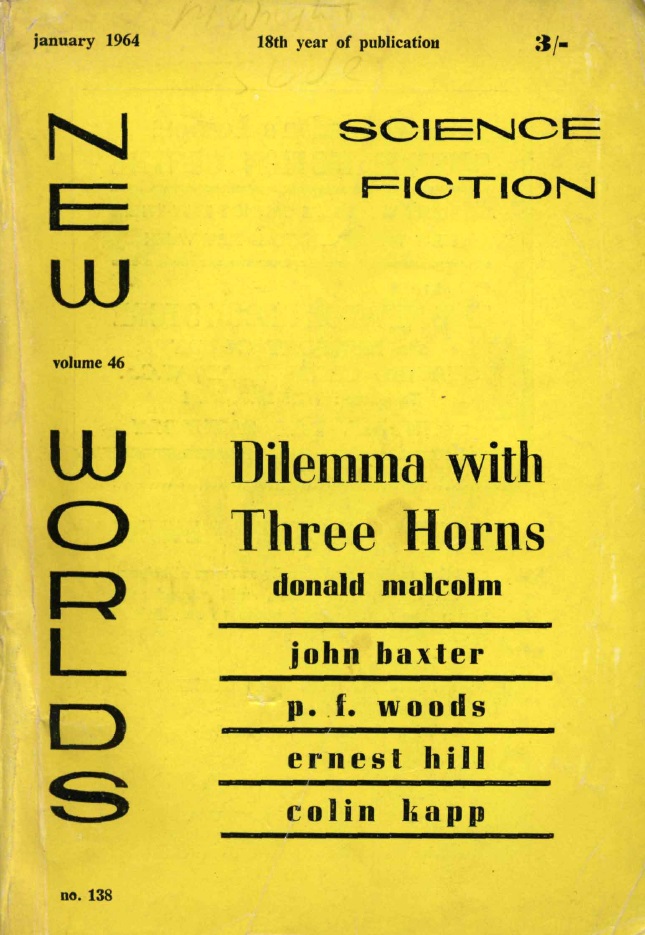

To the January 1964 edition of New Worlds, then.

This month’s cover is a return to the plain but brightly-coloured style of a few months ago. No moonscape, but a lurid shade of yellow. The cover type is easy to read, as there is nothing else there to distract from the reader’s eye. Effectively simple, but will it sell magazines? Not really sure that it matters given the month’s news, which may be Mr. Carnell’s view as well. The general impression is of a magazine on the cheap – how different to the lurid cover of your American issues!

The text inside is, thankfully, a little better.

on political attitudes in s-f, by Mr. John Brunner

Having bemoaned the lack of discussion in last month’s Editorial, this month’s examination of the importance of politics in s-f by Mr. Brunner is much more like the usual article of old. More importantly, it is literate, knowledgeable and even amusing, making the reader examine whether the traditional capitalist view is the only one and where such a review has originated from.

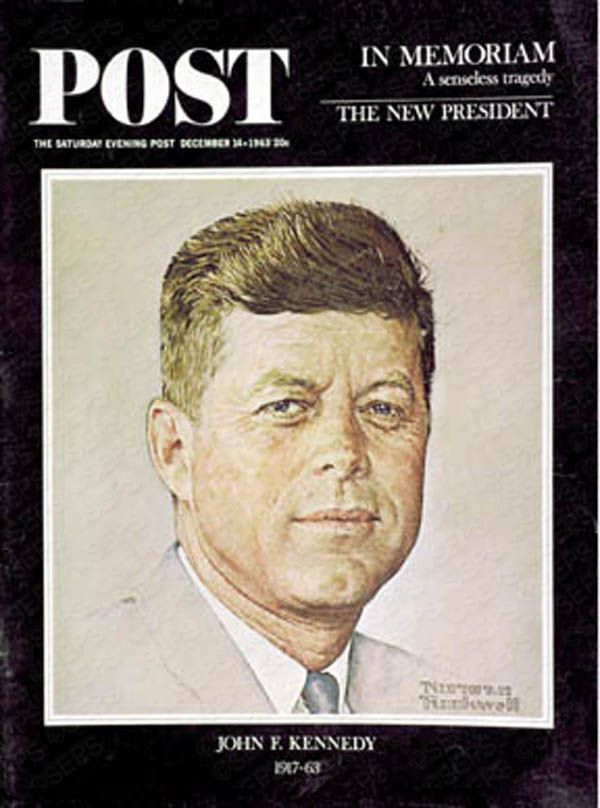

I know that this will have been written months ago, before the events of November, but it is still surreal to read about politics in fiction at a time when real-world politics is in such a state. Democracy is still in flux.

Onto the stories!

dilemma with three horns, by Mr. Donald Malcolm

And here we have the return of Mr. Malcolm’s ongoing P.E.T. (Planetary Expedition Team) series, last seen in February 1963 with twice bitten. This one taps into that ‘sensawunda’ often exhibited by alien environments, to create a straightforward, old-school predicament that would not be remiss of, say, Analog magazine. Our intrepid explorers are given a seemingly impossible choice – stranded from their mothership, do they remain on the newfound planet and die through overexposure to increasing radiation or leave the planet and die because they have to pass through the extremely high Van Allen radiation belt?

To add to this, the third problem of the dilemma is that the intense gravity is causing spinal damage that is untreatable on the planet. I liked it, up to the rather convenient solution, which is plucked out of nowhere and devalues the story overall. What strikes me most though is how this story is not typical New Worlds fare these days. It shows how much the magazine has changed in the last couple of years. 3 out of 5.

the last generation, by Mr. Ernest Hill

And for contrast, this one is more like the “new style” stories of the magazine. A story set far in the future, filled with technical gobbledegook and an attempt to be controversial by combining science with religion. Really its little more than a more complicated version of what Mr. van Vogt was doing in the 1940’s. It is rather full of its own self-importance, whereas I was less impressed. Kudos for trying to be different, but ultimately this falls short of its own ambition. 2 out of 5.

the countenance, by Mr. P. F. Woods

Mr. Woods’s latest resurrects that old idea that the infiniteness of space is too much for mere Humans to cope with. Summarise it as “Space is bad for you”. Not a new idea – Mr. Poul Anderson had something similar in Brain Wave in the 1950’s and then, of course, there’s Mr. Isaac Asimov’s famous Nightfall even further back. There’s even a touch of Mr. Lovecraft’s tales of Cosmic Horror, though the cause here is never clearly explained. It’s entertainingly done through the eyes of a young teenager and his older mentor but is a tad predictable – even with the rather expected and dispiriting twist. 3 out of 5.

toys, by Mr. John Baxter

Set in Mr. Baxter’s home territory of Australia, this story of a cobbler and the toys he creates is an updating of the old Pinocchio story. It makes its point about toys being weapons well – rather appropriately at Christmastime – but is also a little depressing. 3 out of 5.

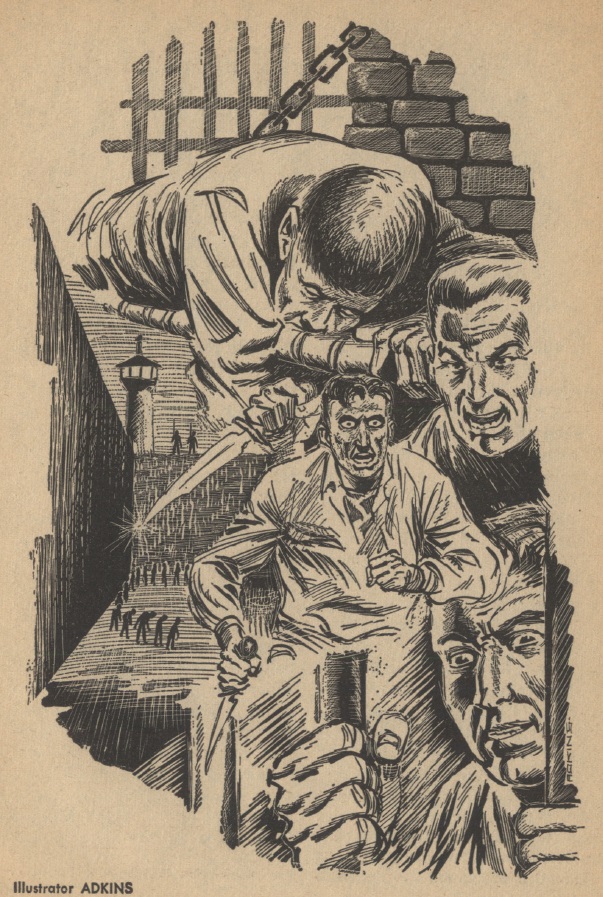

the dark mind (Part 3 of 3), by Mr. Colin Kapp

The last part of Mr. Kapp’s serial continues at a breakneck pace and with not too much sense, full of the same large type face seen in the previous two. This time, Ivan Dalroi, with his dormant powers unleashed and with a single-minded determination for revenge, travels to other worlds to get it. The ending shows us the much bigger picture beyond Dalroi and gives Humanity a reputation for being the tearaway teenagers of the known worlds. It’s a frantic ending to an energetic story, that ties everything up in a bit of a rush at the finish. Whilst I’m always a little wary of a story that depends on textual gimmicks to work (although it did work for Alfred Bester, admittedly) it is good fun, even if it doesn’t dwell with the reader too long. 3 out of 5.

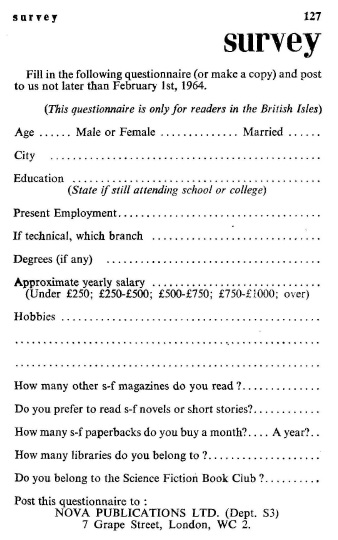

Strangely, and bearing in mind that we now know that we have only a limited time left for New Worlds, there’s a request for readers to contribute to a ‘State of the Nation’ report for 1963. It is the first update since 1958, and so should reflect what Mr. Carnell has been trying to do over the last couple of years. I guess we’ll know before the magazine goes, which may be the point. Perhaps it can be used to determine a fresh start.

Lastly, this month’s Book Reviews are split between editor Mr. John Carnell and book reviewer Mr. Leslie Flood. Mr. Carnell looks at the books imported from your good selves across the water. Of the novels, Mr. Hal Clement’s Mission of Gravity is “in a class of its own” and Ms. Rosel George Brown’s A Handful of Time is “quietly charming”. There are also a couple of anthologies worth looking at. Mr. Martin Greenberg’s anthology Men Against the Stars is a cut-down version of the US version but still “about the best of the current bunch”. Similarly, Mr. T. E. Dikty’s 5 Tales from Tomorrow is also shorter than its US counterpart but is praised for including Mr. Tom Godwin’s The Cold Equations. It is strange to read stories from 1955 appearing here nearly 9 years later, though they do show us how different things were “then” and “now”. We have changed a great deal.

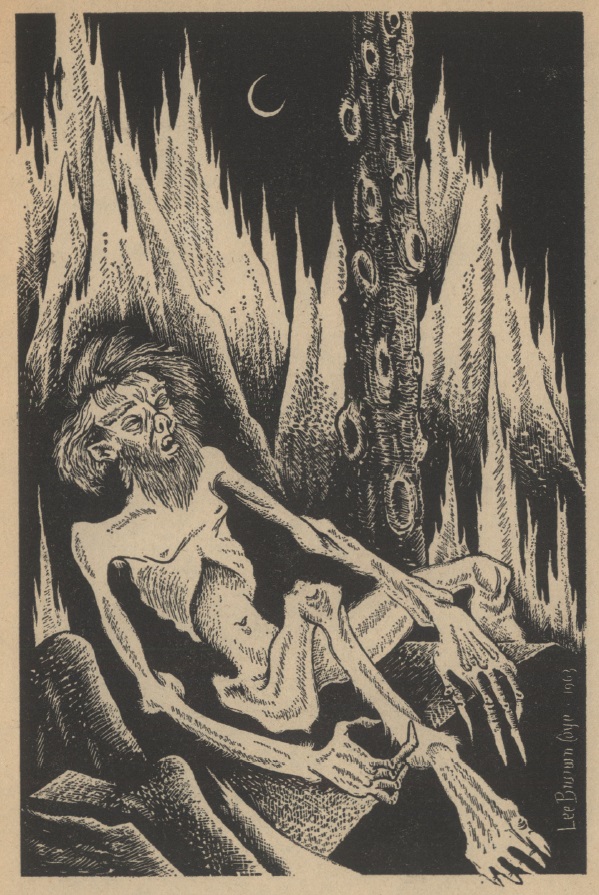

Mr. Flood looks at the new British books new to print here. It’s not all good – Mr. George Hay’s Hell Hath Fury is a story collection from the now-defunct Unknown magazine, but has the reviewer questioning whether this is actually the best of the magazine in a “curiously dated and dispirited collection of ghosts and deviltry”.

Faring better is Mr. Arthur C. Clarke’s juvenile novel Dolphin Island, a minor work but an “entertaining adventure” that “does not talk down beyond the level aimed at.” Moon of Destiny by Mr. Lester de Rey and Destination Moon by Mr. Hugh Walters are also briefly mentioned as “space-flight adventures of some considerable excitement, plausibility and scientific accuracy”.

Summing up

The news of the magazine’s demise has dampened my enthusiasm of the issue a little. I guess that I should make the most of the magazine before it disappears. Again, though, it is a solid issue without being outstanding. I am glad that New Worlds has, unlike many, made it to the end of the year, but I am torn between feeling sad that I’ll never see its like again and bemusement over whether it will be actually missed when it goes.

Until next month.

![[December 27, 1963] Democracy, Doctors and Decline ( <i>New Worlds, January 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631227cover-645x372.jpg)

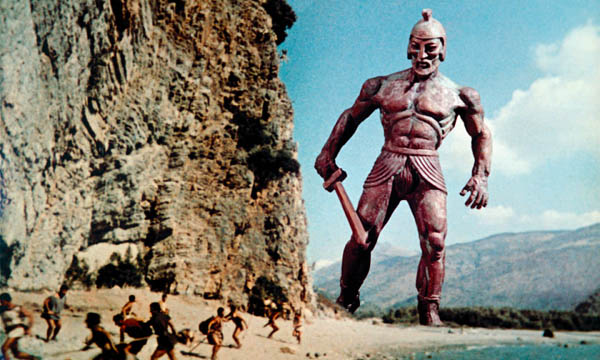

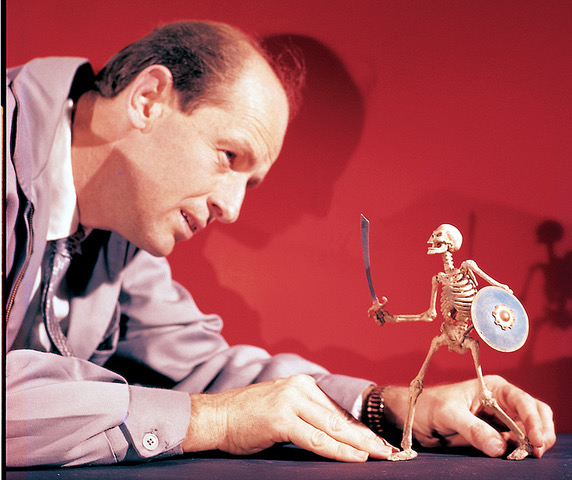

![[December 25, 1963] Animating an Epic (Don Chaffey's <i>Jason and the Argonauts</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631225argonautsposter.jpg)

![[December 23, 1963] Ring Out the Old, Ring In the New (January 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631223cover-487x372.jpg)

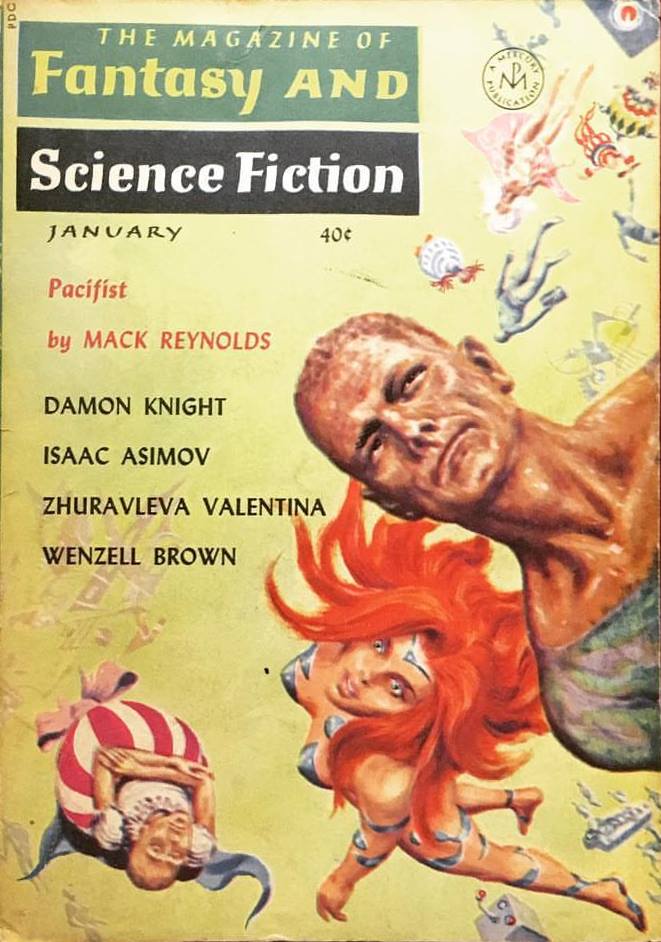

![[December 21, 1963] Soaring and Plummeting (January 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631221cover-661x372.jpg)

![[December 19, 1963] Veiled Secrets (<i>The Outer Limits</i>, Season 1, Episodes 9-12)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631219f-672x372.png)

![[December 17, 1963] The Ink-and-Paper Zoo (February 1964 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/6312017cover-672x372.jpg)

![[December 15, 1963] Our First Outing Into Time And Space (Dr. Who: <i>THE FIREMAKERS</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631215smokingkills-672x372.png)

![[December 13, 1963] SLOW-DOWN (the January 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631213cover-456x372.jpg)

![[Dec. 3, 1963] Dr. Who? An Adventure In Space And Time](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631203hartnell-600x372.jpg)