by Gideon Marcus

About the Author

Laurence M. Janifer (born Larry M. Harris) is a youngish author from New York City. He's distinguished himself as a science fiction writer of at least the second rank, having produced a number of pretty good short stories (including Sword of Flowers, which I awarded the Galactic Star). Janifer also co-wrote the Queen Elizabeth serials with Randall Garrett, and those were decent reading. Thus, his is a name I generally note as an encouraging sign when I see it listed in a magazine's table of contents.

Last year, Larry made the jump to the big time with the recent publication of his first novel, Slave Planet. Fellow Traveler Erica Frank reviewed it in November and thought it a decent, if not unflawed read.

Janifer must have been chained to the typewriter last year because his second book, The Wonder War came out just this month. Given Janifer's track record, I was certain this next effort would be an improvement; thus, I invoked editorial privilege and insisted on being the one to review it.

Well, the joke's on me.

The Wonder War

The setup for Janifer's sophomore effort isn't bad: hundreds of years in the future, the Terran Confederation decides that competition is bad, and the surest way an extraterrestrial planet can develop the technology to become a competitor is through war. After all, the fastest advances seem to come with the impetus of killing one's fellow. So the Confederation places teams of spies on planets with the potential to become adversaries. Their sole mission: to spike the warrior spirit by any means necessary.

The target in The Wonder War is the world of Wh'Gralb. Not only are its inhabitants utterly humanoid (if a trifle shorter than average), but they are currently in a period like the Earth's 1930s. Wh'Gralb's two continents are home to antagonistic nations, one a fascist dictatorship, the other a People's Republic. War has broken out over an island rich in uranium.

Against this backdrop, we are introduced to our team: The sanguine beanpole of a team leader, Glone; the laconic Dempster; and the much put-upon viewpoint character, Plant. Oh, and let's not forget the flattest, most obnoxious caricature — that of Raissa Renny, the girl.

You see, Raissa is the new Coordinator for Propaganda, an insufferable stuck-up know-it-all who is utterly incompetent, and annoying to boot. Chicks, right? The only thing she's got going for her is her knockout good looks. If only she would keep her mouth shut, ya know?

Raissa is imprisoned about a third of the way through the book while checking up on one of the team's embedded agents, and she is not heard from again until the last few pages (when she is rescued, of course, since she can't do anything for herself). Raissa still manages to be present, even in her absence, for Plant moons over her the entire time she's gone. Since Janifer has given us nothing to find likable about the character, one can only assume its Raissa's appearance that has hooked Plant.

Anyway, the rest of the book is a satire with two main points. The first involves how easy it is to snarl up a bureaucracy in red-tape and shenanigans. In fact, so successful are the team's efforts that not a single soldier on either side is killed despite both armies doing their damnedest at it. The other deals with the futility of the team's mission — after all, no matter how long technology on the planet is suppressed, the Confederation will eventually establish trading relations, and Wh'Gralb will get The Bomb, hyperdrive, and whatever else it needs to be a competitor. Per the epilogue (perhaps the best single page of the book), that's exactly what happens.

Again, these are interesting topics in theory. The problem is, Janifer is writing for laughs and utterly failing at it. I don't think I encountered a single lip-quirking quip in all of the book's short 128 pages.

Summing up

The Wonder War is an intriguing premise rendered stillborn by lousy execution; it's essentially an overlong Chris Anvil Analog story. Worse, the tacked on love story and the offensive portrayal of Raissa just kills the thing. It's not awful, exactly. I mean, you can read it.

You just won't ever get those hours back.

Two stars.

— — —

(Need something to cleanse your palate? See all the neat things the Journey did last year!)

![[January 26, 1964] Sophomoric (Laurence M. Janifer's <i>The Wonder War</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640126cover-465x372.jpg)

![[January 22, 1964] The British Are Coming! The Americans Are Here! (February 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640122cover-513x372.jpg)

![[January 16, 1964] Man’s Dark and Troubled History (<i>The Outer Limits</i>, Season 1, Episodes 13-16)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640116e-672x372.png)

![[January 14, 1964] Out Of The Frying Pan (Dr. Who: <i>The Daleks </i>| Episodes 1-4)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640114plungerofdoom-672x372.png)

![[January 12, 1964] SINKING OUT OF SIGHT (the February 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640112cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 10, 1964] Journey to the Stars, Journey into the Self (<i>Starswarm</i>, by Brian Aldiss)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640110cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1964] A Taste of Homely (February 1964 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640108cover-570x372.jpg)

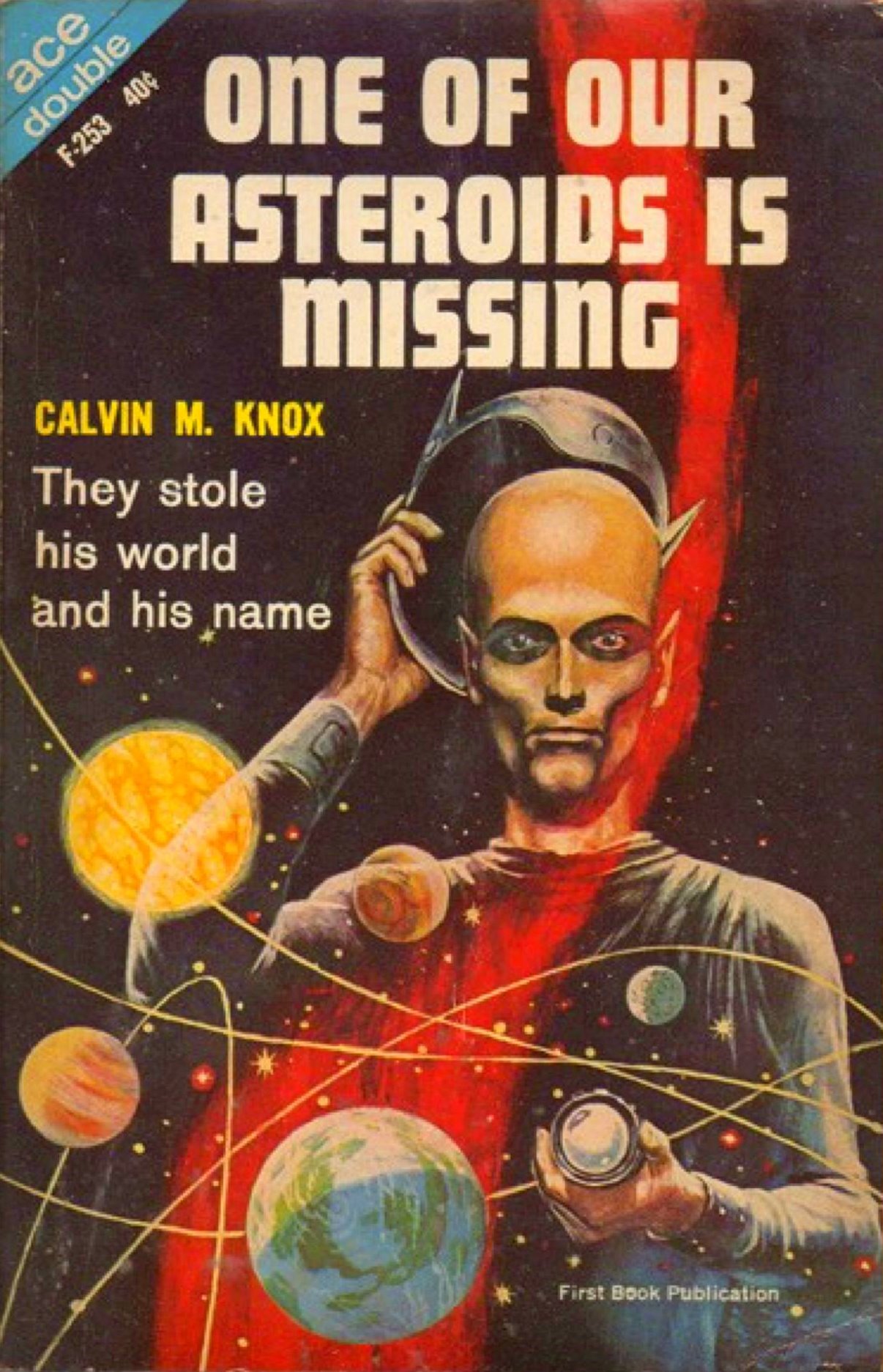

![[January 4, 1964] Something borrowed, something blue (Ace Double F-253)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/640106f253-1-672x372.jpg)

![[January 2, 1964] All's well that ends well (January 1964 <i>Analog</i> science fiction)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640102cover-653x372.jpg)

![[December 29, 1963] Meet the Unknown (<i>Twilight Zone</i>, Season 5, Episodes 9-12)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631229b-672x372.png)