By Jessica Holmes

A New Science Fiction Series Lands At The BBC

Hello, class! Some of you may remember me from last month's article on the Arecibo observatory. For those who don't: hello, my name is Jessica, and I am an artist who likes science.

A lot of people think of the arts and sciences as being at odds with one another, and although I lean towards the arts, I don't see why they have to be separated. The structure of a DNA helix is like a work of sculpture. The exquisite tile patterns found in buildings around the Islamic world are designed according to mathematical principles. Science can be art, and art can be science. So, why am I waffling on about this? Because I believe that the adventure we're about to embark on will prove my assertion.

Produced by Verity Lambert (the BBC's youngest and only woman producer), Doctor Who is the new science fiction series from the BBC, about the mysterious eponymous old man and his machine that allows him to travel through time and space. Along with him are his granddaughter, Susan, and two of her school teachers, Ian Chesterton and Barbara Wright. Together, they'll travel backwards and forwards through history, and upside down and sideways through the universe. According to the Radio Times, each adventure may bring them to the North Pole, distant worlds devastated by neutron bombs (well, THERE'S a relevant story for you!), and even the caravan of Marco Polo. I also hear this show is to have a bit of an educational element, so I'll be looking forward to seeing how that goes.

I wouldn't normally cover such a mundane thing as opening credits, but I think in this case it would be remiss of me not to draw attention to them. The theme music itself is exciting and memorable, and sounds truly from another world from the first few bars. Accompanying this is a novel visual effect (or at least, one I haven't seen before) of abstract swirls pulsating and contorting. I did a little research into how it was done, and it turns out this effect is actually quite simple: it's feedback. Much as placing a microphone close to its own output speaker produces an extremely unpleasant screech, pointing a camera at its own output monitor yields 'howlaround' feedback in the form of these abstract waves.

Enough technical talk. On with the episode.

Wandering the Fourth Dimension

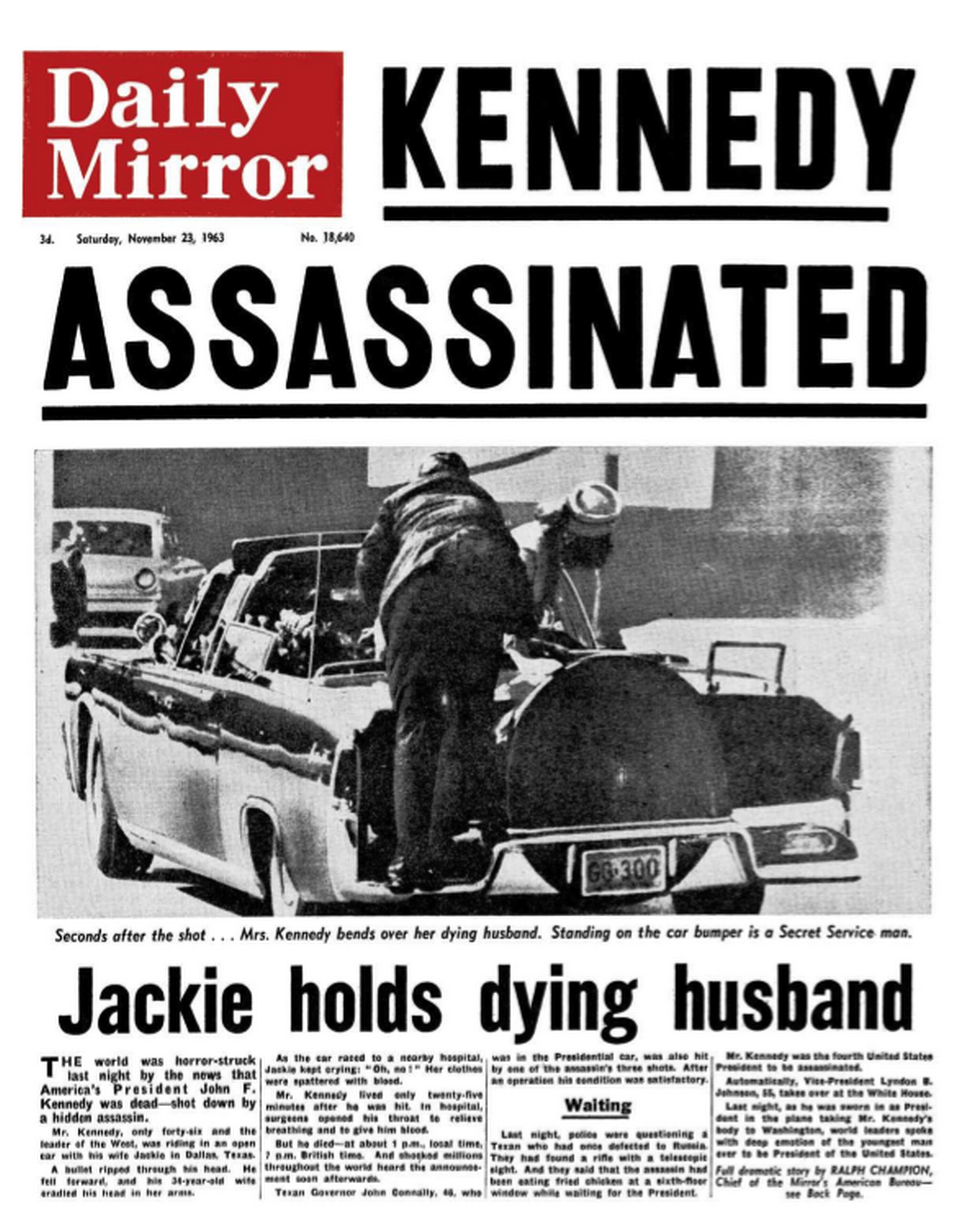

We had a bit of an unusual situation in the release of this premier episode. It was shown, in fact, last week, but for obvious reasons not a lot of people watched it, not to mention the nationwide blackout we suffered that night. It was shown again immediately before the second episode of the serial, which I shall be covering next time.

We fade in from the opening onto a dark, misty shot of a police officer on the beat, passing by a gate labelled with the words 'I.M. Foreman, Scrap Merchant, 76 Totters Lane'. The music gives its cue something is about to happen. The camera closes in on the gate, which swings open to reveal…a junkyard. Shocking, I know. We track forwards into the scrap merchant's yard, passing by a police box as we pan upwards, and then, just as the viewer starts to wonder what we're supposed to be looking at, back to the police box, from within which comes a low hum.

We zoom in on the familiar sign—well, familiar to those of us in my country, anyway. They're quite common, these big blue boxes, though they are sometimes found in other colours, dotted around Britain's streets. Inside each is a telephone connected directly to the local police station, allowing both the public and local police to quickly and easily call for assistance wherever they may be. They can even be used to hold detainees until reinforcements arrive, and I won't even get started on their other, less orthodox uses.

And now we see the title card: An Unearthly Child. This episode was written by Anthony Coburn.

Just when I think we're about to find out what's inside this police box, we cut away to the sound of a school bell, and find ourselves at Coal Hill School, where we meet two of our main characters for the first time: Ian Chesterton, science master, and Barbara Wright, history teacher. These attentive (or perhaps it'd be more accurate to call them nosy) teachers have a conundrum on their hands. It's not an academic matter that ails them, but one of their students, a strange girl named Susan, possesses knowledge far beyond either of them in some fields, while not even being able to say how many shillings are in a pound. It is indeed quite perplexing how such a common piece of knowledge could slip by an otherwise intelligent fifteen year-old (for those unfamiliar, there are twenty shillings in a pound, and twelve pennies in a shilling.) How this girl manages to buy anything without understanding how money works, I couldn't say. She certainly doesn't seem to be from outside Britain; her diction would make my grandmother weep with joy.

From left to right: Jacqueline Hill, Carole Ann Ford and William Russell as Barbara Wright, Susan Foreman, and Ian Chesterton respectively.

Perhaps more perplexing than Susan herself is her address: 76 Totters Lane — the junkyard we saw at the beginning of the episode. In an effort to talk to Susan's grandfather, her only guardian, Ian and Barbara travel to the junkyard one night and await his arrival.

And this, in my opinion, is where the episode starts to get good. It's all been fine up to this point, but there's nothing terribly exciting about watching teachers talk about a difficult student. With the return of the junkyard, the humming police box, and a haze of smog over everything, the mysterious atmosphere kicks back in in full force, and soon enough, my favourite part of the episode arrives.

Enter the Doctor, William Hartnell. There's a good chance you've already heard the name before; he's been in more films over the last decade than I care to mention. Not being the biggest fan of war films, I admit I haven't really seen him in action much, but this Doctor is a far cry from the military men Hartnell normally steps into the shoes of. From the moment he steps into frame, we see just why this programme is called Doctor Who. For all the mystery about Susan, the Doctor blows it out of the water.

William Hartnell as the Doctor.

The Doctor is strange. We get the impression we only hear perhaps a tenth of what he's really thinking, and that his is a mind that races far faster than theirs. It's also clear that this is a man with something to hide; every word out of his mouth is an attempt to deflect the teachers, to persuade them to leave well enough alone. But there's a mischievous twinkle in his eye; we almost get the impression he thinks of this all as a game, an amusement to pass his time. The teachers notice quickly that he's suspiciously keen on keeping them away from the police box. All comes to a head when Susan's voice calls out from inside the box, and fearing her to be in danger, the teachers burst in. At last we get the truth—or at least, our first slice of it.

The police box is bigger on the inside.

All aboard the TARDIS.

Gone is the gloomy junkyard where we had to squint to see; now we're in a bright, open room, lined with all manner of electrical equipment and control panels, and in the centre, a console. This is the TARDIS, short for Time And Relative Dimension In Space. It is both a space ship, and a time machine.

Susan and her grandfather are exiles from another time, another world, cast adrift in time and space, never able to settle in one place for too long, for fear of situations such as these. It's clear both long for home, or at the very least, stability.

"Have you ever thought what it's like to be wanderers in the Fourth Dimension? Have you? To be exiles? Susan and I are cut off from our own planet – without friends or protection. But one day we shall get back. Yes, one day."

The Doctor

The teachers may be people of learning, but this is quite beyond them, as the Doctor notes with a derisive comment. Believing the Doctor to be quite mad and his TARDIS to be an elaborate hoax, the teachers attempt to leave, but to no avail. The Doctor has locked the doors!

In a confrontation with her grandfather, Susan demands that he allow her and the teachers to leave. Seemingly the Doctor acquiesces, but as the rest of the crew make for the door, he begins to laugh in a way greatly reminiscent of the cheeky chuckle my grandfather makes whenever he's cheating at a board game.

With the flick of a switch, that mischievous gleam in the Doctor's eye betrays a hint of malice, or perhaps madness. Quick at work on the controls of his machine, the teachers' pleas to be released fall on deaf ears; his ship is launching, and they're along for the ride.

A wheezing, grinding cacophony rises, the swirling lights from the opening titles return, and all aboard have an expression of great discomfort. Clearly, travel through the extra dimensions is a little more uncomfortable than a ride on the London Underground (if such a thing is even possible). The wheezing noise fades away, and we cut to the outside of the box, but not to the junkyard. Outside the TARDIS is a barren landscape stretching as far as the eye can see, desolate and lifeless. Or is it?

Final Thoughts

So, that was an interesting start to what I hope will be an interesting series. The episode was perhaps a little slow to get going, but things really pick up at the halfway point, with some excellent decisions made by director Waris Hussein. In particular I want to praise the contrast between the dim junkyard and the bright interior of the TARDIS. The jarring transition leaves us as agape as the teachers. The mundane world of modern Britain falls away, and now we're in a place where anything can happen. Good performances all around, but especially from Hartnell, who has a real charm, even if I'm not quite sure as to the motivations of his Doctor character. Eccentric or plain mad? Mischievous or malicious? It's too early to say. The Doctor is an intriguing character, and I'm very excited to see more of his antics, and follow along on the adventure.

![[Dec. 3, 1963] Dr. Who? An Adventure In Space And Time](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631203hartnell.jpg?resize=600%2C372&ssl=1)

![[November 29, 1963] An old doll's new tricks (<i>Twilight Zone</i>, Season 5, Episodes 5-8)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631129c.png?resize=672%2C372&ssl=1)

![[November 27, 1963] … Death, Doctors and Mythology ( <i>New Worlds, November 1963</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631127cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372&ssl=1)

![[November 25, 1963] State of Shock (December 1963 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631125cover.jpg?resize=672%2C372&ssl=1)

![[November 21, 1963] Words for bondage (Laurence M. Janifer's <i>Slave Planet</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631121janiferslaveplanet.png?resize=387%2C372&ssl=1)

![[November 19, 1963] Fuel for the Fire (December 1963 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631119cover.jpg?resize=667%2C372&ssl=1)

![[November 17, 1963] Galactoscope (Three Ace Doubles!)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631117f187.jpg?resize=672%2C372&ssl=1)

![[November 15, 1963] A Sign of Things to Come? (<i>The Outer Limits</i>, Episodes 5-8)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631115c.png?resize=672%2C372&ssl=1)

![[November 13, 1963] Good Cop (the December 1963 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://i0.wp.com/galacticjourney.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631113cover.jpg?resize=669%2C372&ssl=1)