by Kaye Dee

As I noted in my previous article, October was such a busy month for space activity that I had to hold over several items for this month. But November has already provided us with plenty of space news as well. Even though both American and Soviet manned spaceflight is currently on hold while the investigations into their respective accidents continue, preparations for putting astronauts and cosmonauts on the Moon are ongoing and the Moon race is still on!

“Oh, it’s terrific, the building’s shaking!”

Opening the door to human lunar exploration needs an immensely powerful booster, and the successful launch of Apollo-4 a few days ago on 9 November has demonstrated that NASA has a rocket that is up to the task. Although the Saturn 1B rocket intended to loft Apollo Earth-orbiting missions has already been tested, Apollo-4 (also designated SA-501) marked the first flight of a complete Saturn V lunar launcher.

The sheer power of the massive rocket took everyone by surprise. When Apollo-4 took off from Pad 39A at the John F. Kennedy Space Centre, the sound pressure waves it generated rattled the new Launch Control Centre, three miles from the launch pad, causing dust to fall from the ceiling onto the launch controllers’ consoles. At the nearby Press Centre, ceiling tiles fell from the roof. Reporting live from the site, Walter Cronkite described the experience: “… our building’s shaking here. Our building’s shaking! Oh, it’s terrific, the building’s shaking! This big blast window is shaking! We’re holding it with our hands! Look at that rocket go into the clouds at 3000 feet! … You can see it… you can see it… oh the roar is terrific!”

Firing Room 1 in the Launch Control Centre at Kennedy Space Centre, under construction in early 1966. The Apollo-4 launch was controlled from here

Firing Room 1 in the Launch Control Centre at Kennedy Space Centre, under construction in early 1966. The Apollo-4 launch was controlled from here

Could it be that the sound of a Saturn V launch is one of the loudest noises, natural or artificial, ever heard by human beings? (Apart, perhaps, from the explosion of an atomic bomb?) I hope I’ll get the opportunity to hear, and see, a Saturn V launch for myself at some point in the future.

The Power for the Glory

Developed by Dr. Wernher von Braun’s team at NASA’s George C. Marshall Space Flight Centre, everything about the Saturn V is impressive. The 363-foot vehicle weighs 3,000-tons and the thrust of its first-stage motors alone is 71 million pounds! No wonder it rattled buildings miles away at liftoff!

The F-1 rocket motor, five of which power the Saturn V’s S1-C first stage, is the most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine so far developed (at least as far as we know, since whatever vehicle the USSR is developing for its lunar program could have even more powerful motors).

The F-1 rocket motor, five of which power the Saturn V’s S1-C first stage, is the most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine so far developed (at least as far as we know, since whatever vehicle the USSR is developing for its lunar program could have even more powerful motors).

The launcher consists of three stages. The Boeing-built S1-C first stage, when fully fuelled with RP-1 kerosene and liquid oxygen, has a total mass of 4,881,000 pounds. Its five F-1 engines are arranged so that the four outer engines are gimballed, enabling them to turn so they can steer the rocket, while the fifth is fixed in position in the centre. Constructed by North American Aviation and weighing 1,060,000 pounds, the S-II second stage has five Rocketdyne-built cryogenic J-2 engines, powered by liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. They are arranged in a similar manner to the first stage engines, and also used for steering. The Saturn V’s S-IVB third stage has been built by the Douglas Aircraft Company and has a single J-2 engine using the same cryogenic fuel as the second stage. Fully fuelled, it weighs approximately 262,000 pounds. Guidance and telemetry systems for the rocket are contained within an instrument unit located on top of the third stage.

Soaring into the Future

This first Saturn V test flight has been tremendously important to the ultimate success of the Apollo programme, marking several necessary first steps: the first launch from Complex 39 at Cape Kennedy, built especially for Apollo; the first flight of the complete Apollo/Saturn V space vehicle; and the first test of Apollo Command Module’s performance re-entering the Earth's atmosphere at a velocity approximating that expected when returning from a lunar mission. In addition, the flight enabled testing of many modifications made to the Command Module in the wake of the January fire. This included the functioning of the thermal seals used in the new quick-release spacecraft hatch design.

Up, Up and Away!

Apollo-4 lifted off on schedule at 7am US Eastern time. Just 12 minutes later it successfully placed a Command and Service Module (CSM), weighing a record 278,885 pounds, into orbit 115 miles above the Earth. This is equivalent to the parking orbit that will be used during lunar missions to check out the spacecraft before it embarks for the Moon.

After two orbits, the third stage engine was re-ignited (itself another space first) to simulate the trans-lunar injection burn that will be used to send Apollo missions on their way to the Moon. This sent the spacecraft into an elliptical orbit with an apogee of 10,700 miles. Shortly afterwards, the CSM separated from the S-IVB stage and, after passing apogee, the Service Module engine was fired for 281 seconds to increase the re-entry speed to 36,639 feet per second, bringing the CSM into conditions simulating a return from the Moon.

An image of the Earth taken from an automatic camera on the Apollo-4 Command Module

After a successful re-entry, the Command Module splashed down approximately 10 miles from its target landing site in the North Pacific Ocean and was recovered by the aircraft carrier USS Bennington. The mission lasted just eight hours 36 minutes and 54 seconds (four minutes six seconds ahead of schedule!), but it successfully demonstrated all the major components of an Apollo mission, apart from the Lunar Module (which is still in development) that will make the actual landing on the Moon’s surface. In a special message of congratulations to the NASA team, President Johnson said the flight “symbolises the power this nation is harnessing for the peaceful exploration of space”.

Goodbye Lunar Orbiters…

While Apollo’s chariot was readied for its first test flight, NASA has continued its unmanned exploration of the Moon, to ensure a safe landing for the astronauts. In August, Gideon gave us an excellent summary of NASA’s Lunar Orbiter programme, the first three missions of which were designed to study potential Apollo landing sites. Lunar Orbiter-3, launched back in February this year, met its fate last month when the spacecraft was intentionally crashed into the lunar surface on 9 October. Despite the failure of its imaging system in March, Lunar Orbiter-3 was tracked from Earth for several months for lunar geodesy research and communication experiments. On 30 August, commands were sent to the spacecraft to circularise its orbit to 99 miles in order to simulate an Apollo trajectory.

Lunar Orbiter-3 image of the Moon's far side, showing the crater Tsiolkovski

Lunar Orbiter-3 image of the Moon's far side, showing the crater Tsiolkovski

Each Lunar Orbiter mission has been de-orbited so that it will not become a navigation hazard to future manned Apollo spacecraft. Consequently, before its manoeuvring thrusters were depleted, Lunar Orbiter 3 was commanded on 9 October to impact on the Moon, hitting the lunar surface at 14 degrees 36 minutes North latitude and 91 degrees 42 minutes West longitude. Co-incidentally, Lunar Orbiter-4, which failed back in July and could not be controlled, decayed naturally from orbit and impacted on the Moon on 6 October. Lunar Orbiter-5, launched in August, remains in orbit.

…Hello Surveyor 6

A month after the demise of the Lunar Orbiters, NASA’s Surveyor-6 probe has made a much softer landing on the lunar surface, achieving a “spot on” touchdown in the rugged Sinus Medii (Central Bay – it’s in the centre of the Moon's visible hemisphere) on 10 November (Australian time; 9 November in the US). This region is a potential site for the first Apollo landing, but since it appeared to be cratered and rocky, mission planners needed to know if its geological structure (different to the ‘plains’ areas where earlier Surveyor missions have landed) could support the weight of a manned Lunar Module.

Only an hour after landing safely, Surveyor-6 was operational and sent back pictures of a lunar cliff about a mile from its landing point, which has been described as “the most rugged feature we have yet seen on the Moon”. The first panoramas from Surveyor indicate that the landing site is not as rough as anticipated, and seems suitable for an Apollo landing.

Deep Space Network stations in Australia are helping to support the Surveyor-6 mission, as well as Surveyor-5, that landed in the Mare Tranquilitatis (Sea of Tranquillity) in September and is still operational. Hopefully both spacecraft will survive the next lunar night, commencing two weeks from now. NASA plans to send one more Surveyor probe to the Moon, in January, so look out for a review of the completed Surveyor programme early next year.

Watching the Sun for Astronaut Safety

With the Sun moving towards its maximum activity late next year or early in 1969, and likely to still be very active when the Apollo landing missions are occurring (assuming that the programme resumes some time within the next 12 months), NASA has wasted no time in launching another spacecraft in its Orbiting Solar Observatory (OSO) series, to help characterise the effects of solar activity in deep space. A NASA spokesman was recently quoted as saying that “A study of solar activity and its effect on Earth, aside from basic scientific interest, is necessary for a greater understanding of the space environment prior to manned flights to the Moon”.

OSO-4 under construction

OSO-4 under construction

Launched on 18 October, OSO-4 (also known as OSO-D) is the latest satellite developed under the leadership of Dr. Nancy Grace Roman, NASA’s first female executive, who is Chief of Astronomy and Solar Physics. The satellite is equipped to measure the direction and intensity of Ultraviolet, X-ray and Gamma radiation, not just from the Sun, but across the entire celestial sphere.

The OSO-4 spacecraft, like its predecessors, consists of a solar-cell covered “sail” section and a “wheel” section that spins about an axis perpendicular to the pointing direction of the sail. The sail carries a 75 pound payload of two instruments that are kept pointing on the centre of the Sun. The wheel carries a 100 pound payload of seven instruments and rotates once every two seconds. This rotation enables the instruments to scan the solar disc and atmosphere as well as other parts of the galaxy. The satellite’s extended arms give it greater axial stability.

Hopefully, OSO-4 will have a long lifespan, producing data as solar activity increases across the Sun’s cycle, and enhancing safety for the Apollo and Soviet crews who will venture beyond the protection of the van Allen belts on their way to the Moon.

What are the Soviets Up To?

The USSR has been remarkably quiet about its manned lunar programme. One could almost think that they had given up racing Apollo to the Moon, if not for the rumours and hints that constantly swirl around. Rumours abounded at the time of the tragically lost Soyuz-1 mission that it was intended to be a space spectacular, debuting in the Soyuz a new, much larger spacecraft which would participate in multiple rendezvous and docking manoeuvres, and possibly even crew transfers, with one or more other manned spacecraft.

Such a space feat has yet to occur, but the mysterious recent space missions of Cosmos-186 and 188 suggest that the Soviets have something of the sort in mind for the future, and are still quietly working to develop the techniques that they will need for lunar landing missions and/or a space station programme.

It Takes Two to Rendezvous

On 27 October, Cosmos-186 was launched into a low Earth orbit, with a perigee of 129 miles and an apogee of 146 miles and an orbital period of 88.7 minutes. Cosmos-187 was launched the following day, and there has been speculation that it was intended to be part of a rendezvous and docking demonstration with Cosmos-186 but was placed into an incorrect orbit. However, as is so often the case with Cosmos satellites, the Soviet authorities only described their missions as continuing studies of outer space and testing new systems, so the actual purpose of this mission remains a mystery.

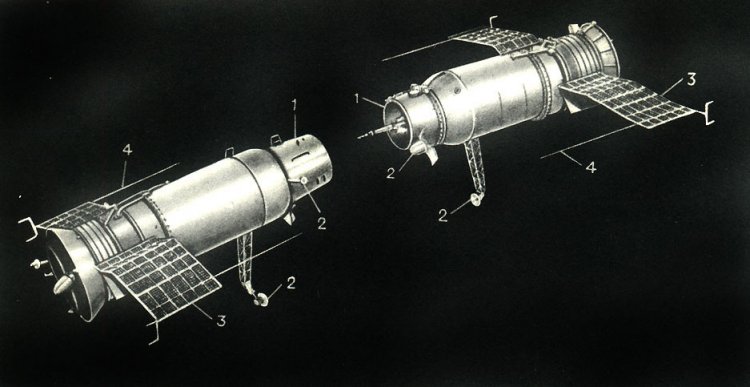

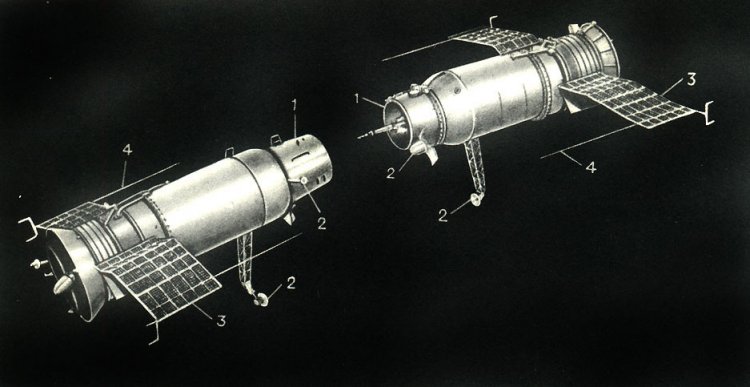

A rare Soviet illustration of what is believed to be the Cosmos-186-188 docking

However, Cosmos-186 was joined by a companion on 30 October, when Cosmos-188 was placed into a very similar orbit with a separation of just 15 miles. This clearly demonstrates the precision with which the USSR can insert satellites into orbit. The two spacecraft then proceeded to perform the first fully automated space docking (unlike the manual dockings performed by Gemini missions from Gemini-8 onwards), just an hour after Cosmos-188 was launched. Soviet sources, and some electronic eavesdropping by the now-famous science class at Kettering Grammar School in England, using surprisingly unsophisticated equipment, indicate that Cosmos-186 was the ‘active’ partner in the docking. It used its onboard radar system to locate, approach and dock with the ‘passive’ Cosmos-188.

While the two spacecraft were mechanically docked, it seems that an electrical connection could not be made between them, and no other manoeuvres appear to have been carried out while Cosmos-186 and 188 were joined together. Perhaps there were technical issues surrounding the docking, but an onboard camera on Cosmos-186 did provide live (if rather low quality) television images of the rendezvous docking and separation, and some footage was publicly broadcast.

After three and a half hours docked together, the two satellites separated on command from the ground and continued to operate separately in orbit. Cosmos-186 made a soft-landing return to Earth on 31 October, lending credence to the speculations that it was testing out improvements to the Soyuz parachute system, while Cosmos-188 reportedly soft-landed on 2 November.

Speculating on Soviet Space Plans

Was Cosmos-186 a Soyuz-type vehicle, possibly testing out modifications made to prevent a recurrence of the re-entry parachute tangling that apparently led to the loss of Soyuz-1 and the death of Cosmonaut Komarov? Building on speculations from the time of the Soyuz-1 launch, there have even been suggestions that Cosmos-186, while unmanned, was a spacecraft large enough to hold a crew of five cosmonauts. There is also speculation that Cosmos-188 may have been the prototype of a new propulsion system for orbital operations. Does this mean, then, that the USSR is planning some kind of manned spaceflight feat in orbit to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Communist Revolution? Or that it will soon attempt a circumlunar flight, to reach the Moon ahead of the United States?

Whatever their future plans may be, the automated rendezvous and docking of two unmanned spacecraft in Earth orbit shows that the USSR’s space technology is still advancing rapidly. The joint Cosmos 186-188 mission proves that it is possible to launch small components and assemble them in space to make a larger structure, even without the assistance of astronauts. This means that massive rockets like the Saturn V might not be required to construct space stations in orbit, or even undertake lunar missions, if the project is designed around assembling the lunar spacecraft in Earth orbit. Has the Cosmos 186-188 mission therefore been a hint of what the USSR's Moon programme will look like, in contrast to Apollo? Only time will tell…

![[April 22, 1970] “Houston, We’ve had a Problem Here!” (Apollo-13 emergency in space)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Apollo-13-13-672x372.jpg)

![[November 12, 1967] Still in the Race! (Apollo-4, Surveyor-6, OSO-4 and Cosmos-186-188)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Apollo-4-672x372.jpg)

The F-1 rocket motor, five of which power the Saturn V’s S1-C first stage, is the most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine so far developed (at least as far as we know, since whatever vehicle the USSR is developing for its lunar program could have even more powerful motors).

The F-1 rocket motor, five of which power the Saturn V’s S1-C first stage, is the most powerful single combustion chamber liquid-propellant rocket engine so far developed (at least as far as we know, since whatever vehicle the USSR is developing for its lunar program could have even more powerful motors).

Lunar Orbiter-3 image of the Moon's far side, showing the crater Tsiolkovski

Lunar Orbiter-3 image of the Moon's far side, showing the crater Tsiolkovski

OSO-4 under construction

OSO-4 under construction