by Gideon Marcus

Three and Two make Two

I imagine Vegas bookies are tearing their hair out trying to predict the Presidential race this year. On January 1, the hard money would have been on President Johnson beating Governor George Romney in a fairly easy race. Then McCarthy and Nixon won in New Hampshire. The former sent LBJ announcing his resignation and the latter gave the former Vice-President the first victory of his own since 1950.

Then Bobby Kennedy jumped in, trying to steal McCarthy's lunch. Inevitably, Vice President Humphrey threw his hat in the ring, instantly commanding the loyalty of most democratic party bosses. Meanwhile, Romney's dropped out, but Nelson Rockefeller, who said he wasn't going to play this year, has jumped in.

So, who will face each other come Labor Day? It's anyone's guess, especially since both McCarthy and Kennedy just won recent primaries. I guess we'll have to see if the New York Governor's campaign has legs, and if Humphrey's position translates to delegates at the convention.

Stay tuned…

Nine to Rule Them All

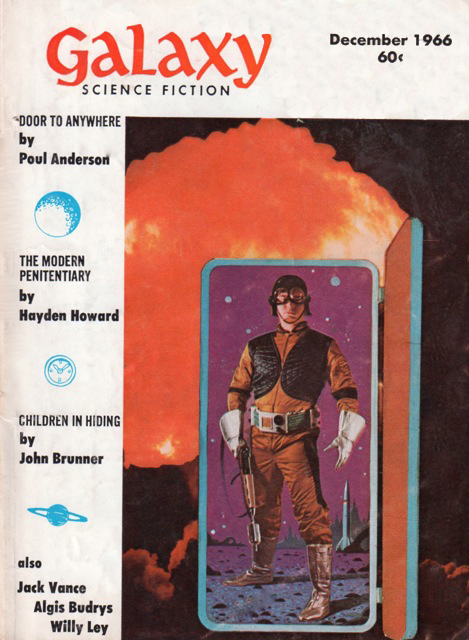

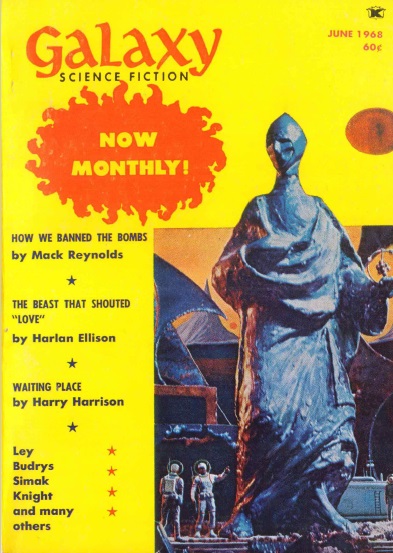

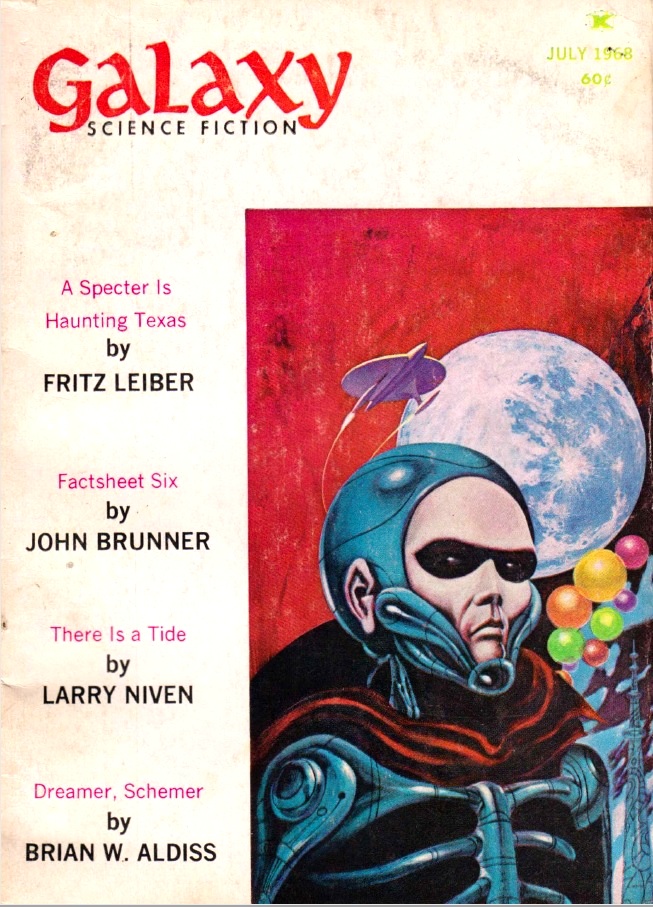

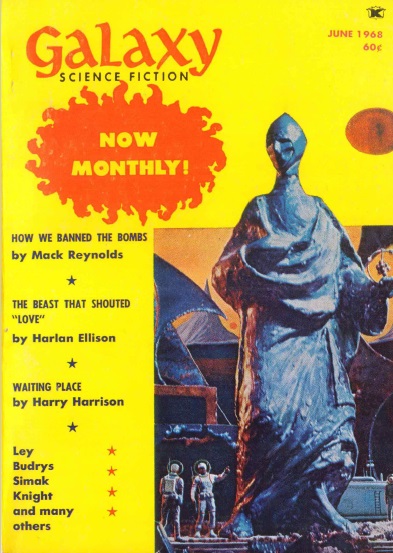

It's similarly a horse race with the latest issue of Galaxy, which presents a solid batch of stories. Which one is the best? That's a hard choice, too!

by Paul E. Wenzel

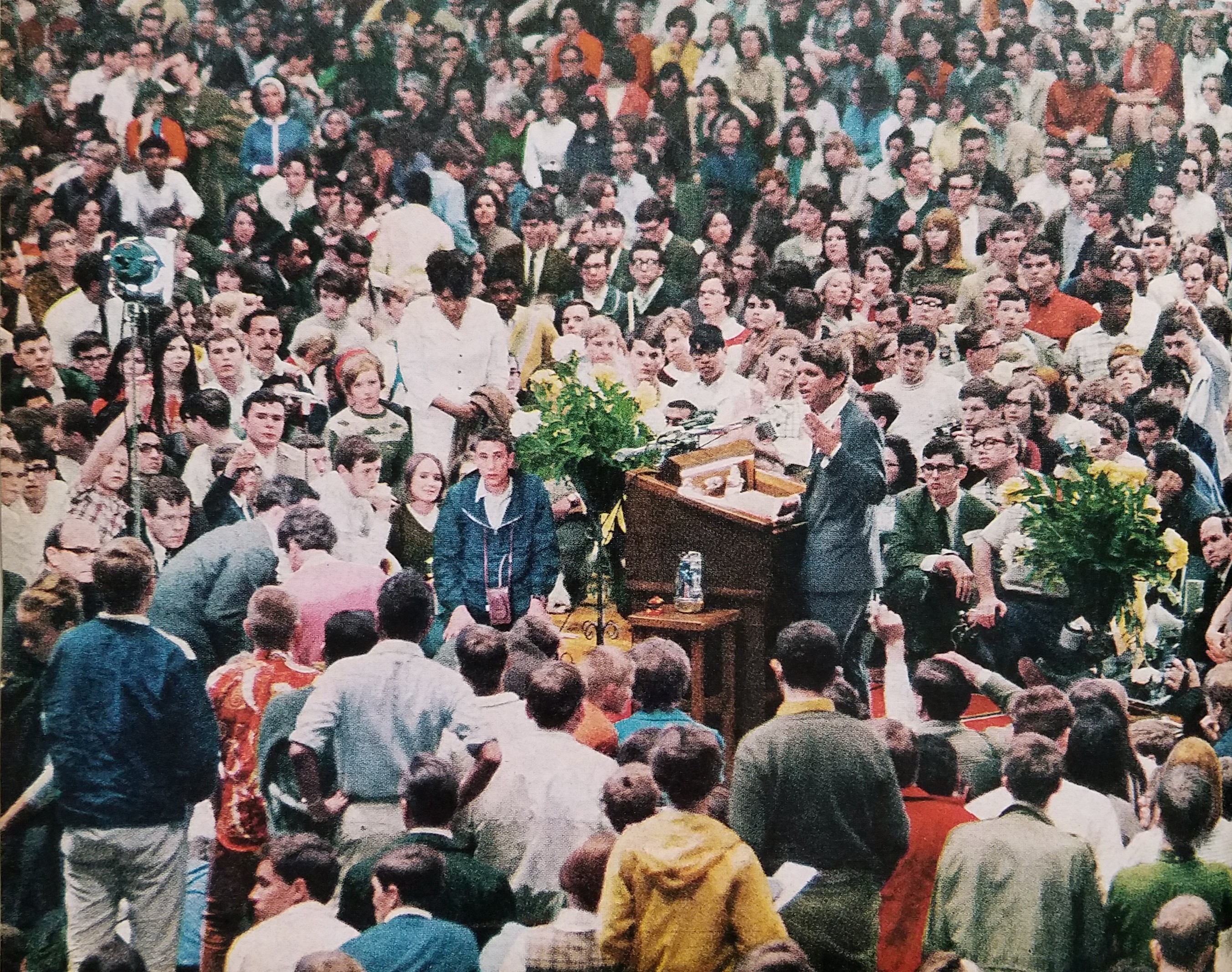

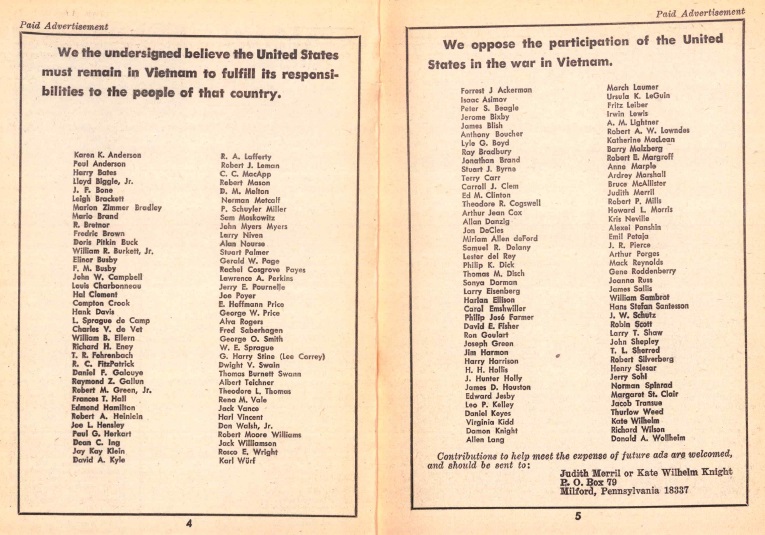

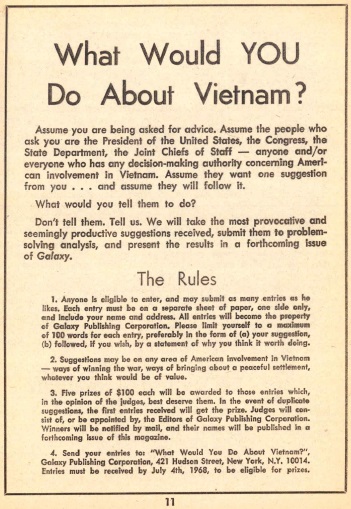

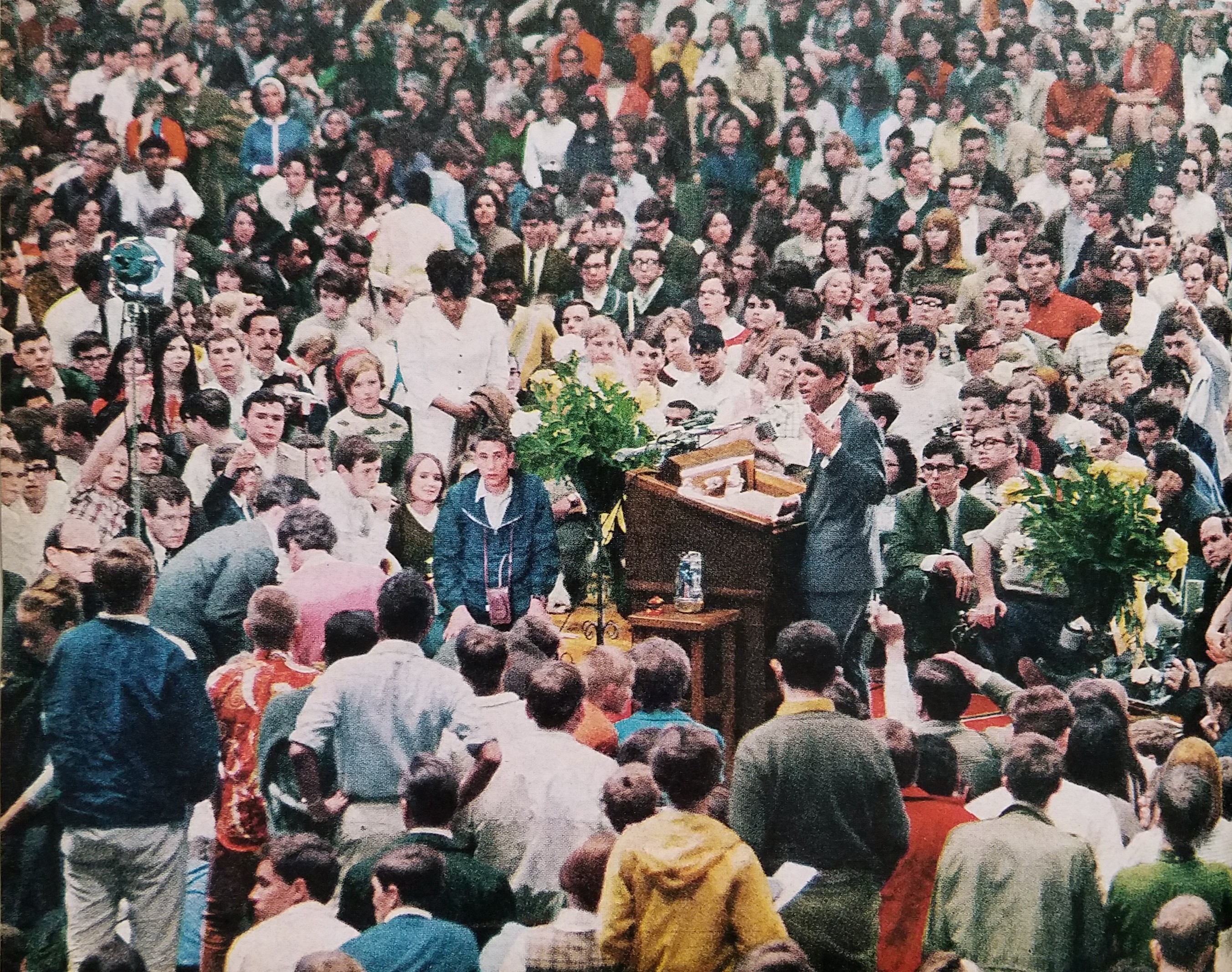

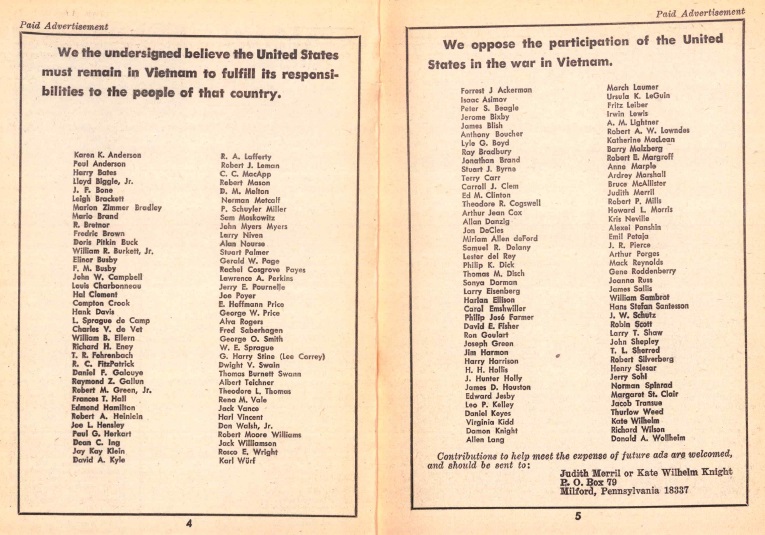

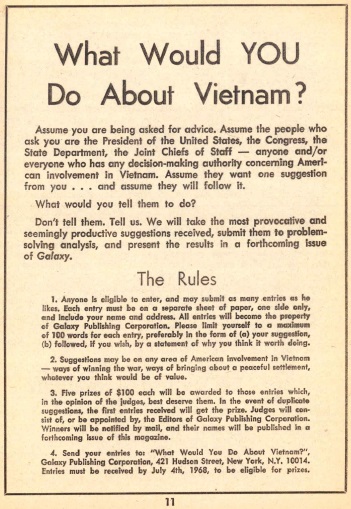

But first, the editorial. Remember a few months ago F&SF ran competing ads from SF authors for and against the war in Vietnam?

Well, now Pohl's mags are doing it.

Pohl (Galaxy's editor) says it's not just enough to bitch about it. Someone needs to come up with a solution. He figures SF fans are about the smartest people around, so why don't we try our hand at it?

So now there's a contest, first prize $1,000, details at the bottom of this article. Of course, given that you can't devote more than 100 words to the issue, and given that the war has been going on since 1945, in one way or another, and given that a lot of smart people have been trying to fix this thing…I somehow feel 100 words is not enough.

Or as my friend the divorce lawyer likes to say: "Imagine trying to fix a car. Now try to imagine fixing that car while another party is actively trying to dismantle it."

Yeah. Lots of luck, Pohl.

On to the stories!

The Beast That Shouted Love, by Harlan Ellison

by Jack Gaughan

Ever wonder why all people seem to go psycho all of sudden? Why a race with countless religious texts devoted to peace, harmony, and brotherhood just goes buggy every so often?

What if some other planet, in order to preserve their peace, harmony, and brotherhood, is beaming all their psycho energy to us? Sort of a bad emotions disposal process.

This is one of Ellison's lesser pieces. It probably means a lot to him, but it's rather disjointed and vague and not as profound as he wants it to be.

Three stars.

How We Banned the Bombs, by Mack Reynolds

by Vaughn Bodé

Right now, the world population is 3.5 billion and rising. Naturally, this has been the cause of concern and the topic of more than a few science fiction stories. Bombs is one of the lesser efforts.

Reynolds posits a Reunited Nations government so powerful that, in response to the Population Explosion, it can enforce a ten-year ban on childbirth through mandatory provision of contraceptives to women. At the end of the ban, it turns out that the contraceptive drug's effect was permanent, and all human women are completely sterile.

This, by the way, is the end of the story. The rest of it involves characters talking to each other, telling tales they all know about how the world ended up in this predicament (which doesn't make for much of a story).

The whole premise is silly. The population in this projected, not-too-distant future is 3.5 billion, same as it is now, yet resources are so scarce, they're banning the production of alcohol so as to husband their grain crops. Somehow, the ReUN can sterilize EVERY woman on Earth, none slipping through the cracks. And then, no one foresees or predetermines that the universal contraception has adverse effects.

In the words of Laugh-In's Joanne Worley: "Dummmmmb!"

One star.

Detour to Space, by Robin Scott Wilson

(uncredited artist)

Object 3574 is circling the Earth in a polar orbit. Unannounced, the General is convinced it's a secret Russkie bomb. NASA's long-hair thinks otherwise. The majority decides to send up an Apollo to check it out. The object is covered in green slime and pebbled with tektites, suggesting extraterrestrial origin…

There's a lot to like about this tale, especially the sting at the end of it. Scott convincingly describes the apprehension with which we Americans greet the arrival of a new star in the heavens. I know I scour the papers and call my Vandenberg buddies whenever anything goes up to get some insight into otherwise classified launches.

Where the story beggars credibility is the use of Apollo spacecraft, launched from Vandenberg, to intercept 3574. You just can't do it–there's no way to get a Saturn there. Much more likely would be to send up an Air Force Gemini (they're making them for the planned Manned Orbiting Laboratory). But that would have killed the story.

This is what happens when you know too much about a subject, reviewing a story by someone who doesn't quite know enough… three stars.

Daisies Yet Ungrown, by Ross Rocklynne

Joe Wehrle, Jr.

After the big bombs created the time-space Rift, God told Rickert to jump through with Sears catalog robots and claim a new world 350,000 trillion light years from Earth. But this is so far away that God's grace cannot reach, and Lucifer's tool, the newcomer Dorothy, has arrived to take his planet away from him.

This is an odd, poetic story that you, at first, think is going to be satirical, sort of a cross between Sheckley and Bunch. Instead, it's kind of pretty and sweet, way different than I was expecting.

Three stars.

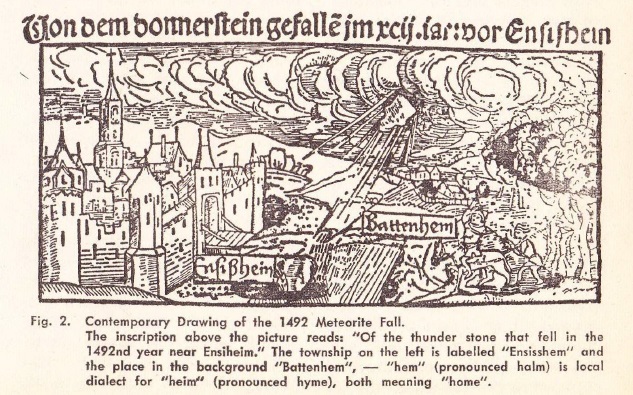

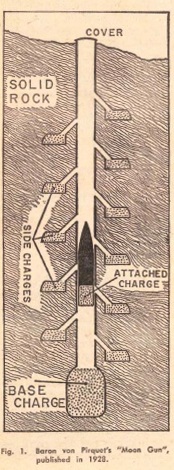

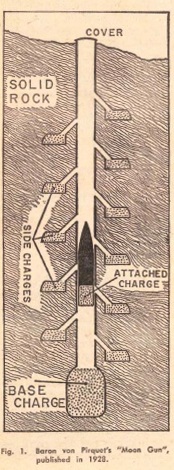

For Your Information: Jules Verne, Busy Lizzy and Hitler, by Willy Ley

This is a pretty interesting piece on attempts using a gun rather than a rocket to fire a projectile, if not into space, at least a terrific distance. Essentially, it's like a rocket, but with the propellant on the outside.

Long story short: rockets are better. Four stars.

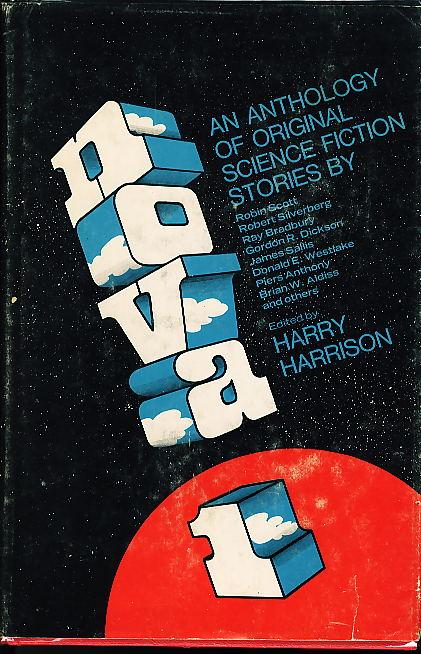

Waiting Place, by Harry Harrison

(uncredited artist)

A man taking the matter transmitter home finds himself in the future version of Devil's Island, a colony for hardened criminals. Surely, there has been some kind of malfunction, for he can remember no crime. But the wheels of justice never make a mistake, or do they?

This would be a fairly slight tale if not for the execution. Luckily, Harrison (who I understand has just retired from the editor helm of Fantastic and Amazing) is a master of execution.

Four stars.

The Garden of Ease, by Damon Knight

by Jack Gaughan

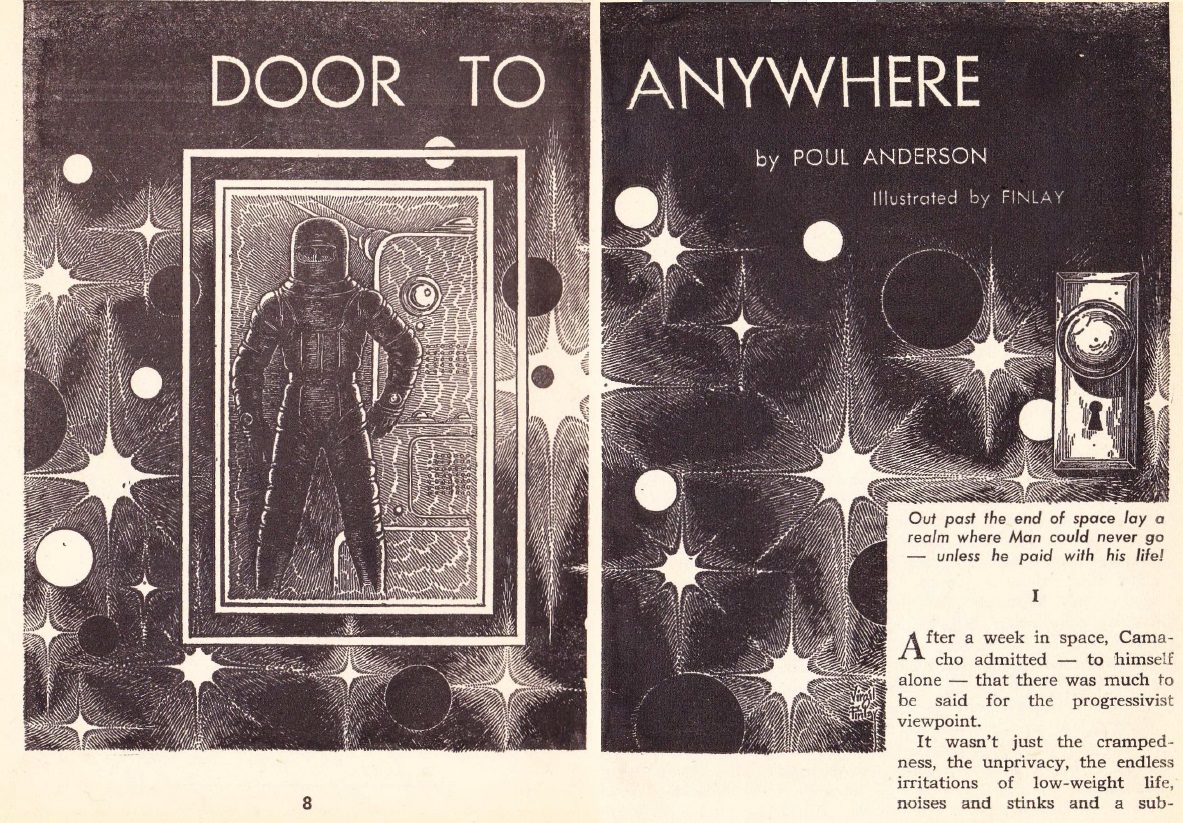

As expected, the first adventure of Thorinn, a human raised by trolls in a Nordic nightmare, has a sequel. Last time, the resourceful Thorinn had been tossed into a deep well as an offering to the gods to end a ceaseless winter. Making his way through the caves he found, Thorinn discovered a hatch that opened not onto but above a new world. This story details what he finds below.

In an almost Oz-like setting, the people of the Vale enjoy a life of complete ease. The grasshopper men and the doughwomen and the fancymen and the children, they eat the food that grows on trees and bushes, they frolic, they discuss, and when they want adventure, they seal themselves up in the pleasure pods for the night…or sometimes an eternity.

Thorinn is the snake in the garden, slowly poisoning the place with his foreignness and his willingness to kill. Ultimately, he hatches an escape plan, but not before leaving his mark.

This is an interesting episode, but not as compelling or as clever as the first one. Three stars.

Booth 13, by John Lutz

Here's a new author, or at least, new to me. John paints a grim future in which populational ennui has settled in. All that's left is war, the tranquilizer lysogene, and the death booths. If life gets just a bit too monotonous, there's always a quick and easy exit–and now, people are taking it in ever-increasing numbers.

It's not badly done, but my biggest issue is not enough explanation is given as to why everyone is so melancholy. Perhaps that's the point–if you give everyone an easy out, even the mildest inconveniences can trigger a snap decision. Or maybe the author is simply extrapolating from the current, profound American despondency.

At the very least, I liked it better than Sales of a Deathman.

Three stars.

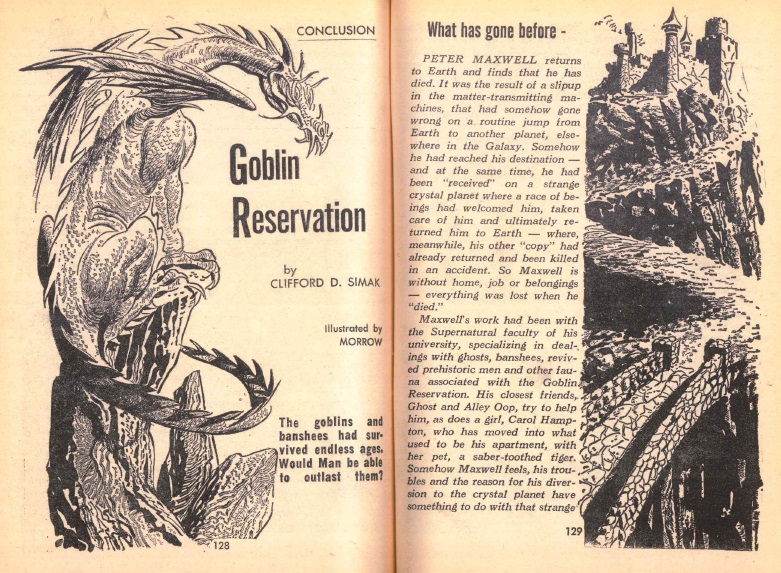

Goblin Reservation (Part 2 of 2), by Clifford D. Simak

by Gray Morrow

Last time, if you recall, Pete Maxwell has gone off to do research at the crystal planet, a world with the accumulated knowledge of two universes (it had lived through the last Big Crunch). The fading intelligences of the planet offered all of its wisdom in exchange for The Artifact, a featureless black object dating back to the Jurassic period. When Maxwell got back to Earth, he found that he'd already come back, duplicated by some quirk of matter transfer, and died.

This datum takes a back seat to bigger concerns–the Wheelers, bags of insect colonies bent on acquiring the lore of the crystal planet, have already purchased The Artifact, and once it is in their possession, plan to take over the universe. It is up to Maxwell, his tentative ally Carol, her sabre-tooth tiger Sylvester, their Neanderthal pal Alley Oop, the Ghost, William Shakespeare, the librarian who sold The Artifact, the goblin O' Toole, and several bridge-dwelling trolls to somehow stop the transaction before it's too late.

I must say, Simak pulls off a large set of emotional tones very well. You feel the sense of impending dread when it seems the Wheelers have clinched the deal. The comedic scenes are genuinely amusing. Yet, there is a grounding to the story that keeps it from being Laumerian or Anvilian lampoon. The revelations of the true nature of the fairies, little people, banshees, and whatnot are pretty good, too, though a bit abrupt. Perhaps they'll have more time to breathe in the novel version.

The only bit I had trouble with was The Wheelers, for whom I felt sympathy once I learned their motivation. There's an undertone of unconscious racism where they're concerned–they're bad because they're icky, different. When you learn what their status had been vis-à-vis the crystal planet, it all becomes a bit more unsettling.

Nevertheless, pleasant reading by a master. Four stars.

Picking a Winner

Well. It's obvious which story was the loser here (let's just call the Reynolds tale 'Harold Stassen'). But as to a winner, well that's a little harder. Several of the three-stars are quite nice; my four-star to the Harrison may be arbitrary. We can exclude the Simak because it's a serial, but it anchors this and the last issue well.

I suppose in an issue where (all but one of) the stories are good, the real winner is…us.

Happy reading! And don't forget to write to Pohl…

</small

</small

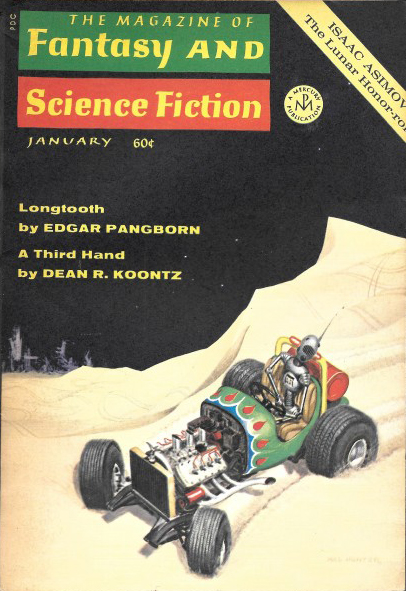

![[June 24, 1970] In love with "Ishmael in Love" (July <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700624fsfcover-409x372.jpg)

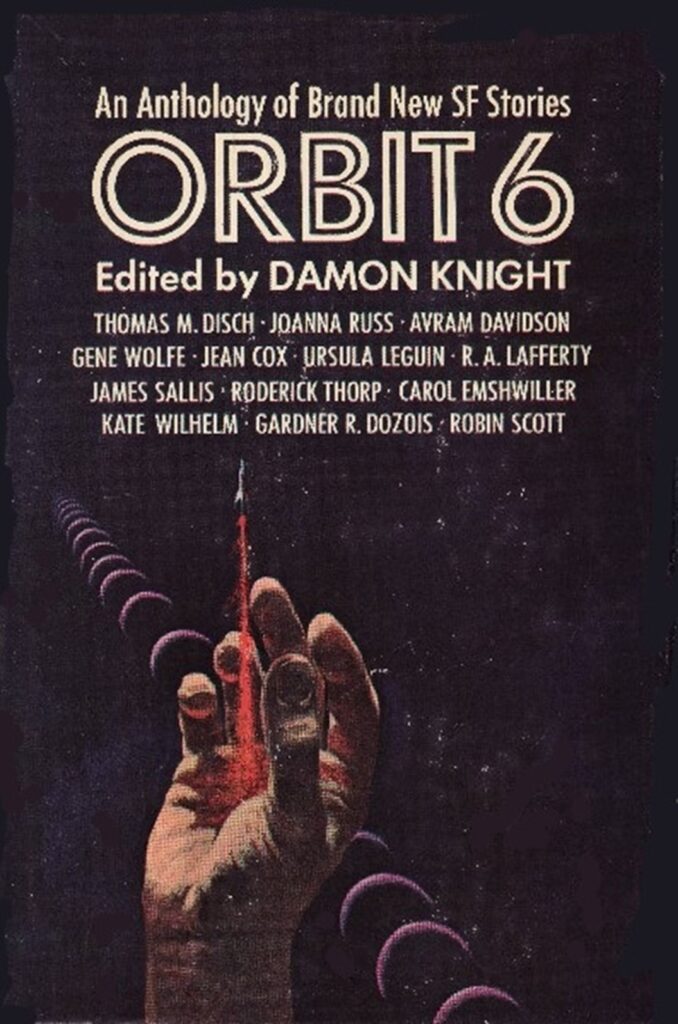

![[March 12, 1970] It’s A Dog’s Life (<i>Orbit 6</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Orbit-F-672x372.jpg)

![[March 4, 1970] Harry's Heroes (<em>Nova 1</em>, edited by Harry Harrison)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/NVFCNDXTDF1970-421x372.jpg)

![[December 20, 1969] Stars above, stars at hand (January 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/691220fsfcover-406x372.jpg)

![[October 20, 1969] There was a ship (November 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Venture-1969-11-Cover-480x372.jpg)

The SS Manhattan breaking through the ice of the Northwest Passage.

The SS Manhattan breaking through the ice of the Northwest Passage. Art by Tanner

Art by Tanner![[January 28, 1969] Slidin' (February 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690128cover-672x372.jpg)

A Womanly Talent, by Anne McCaffrey

A Womanly Talent, by Anne McCaffrey

![[June 10, 1968] Froth and Frippery (July 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680610cover-653x372.jpg)

![[May 10, 1968] Horse race (June 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/680510cover-393x372.jpg)

![[March 10, 1967] Mediocrités, Slayer of Magazines (April 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670310cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 12, 1966] A Family Tradition (December 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661112cover-469x372.jpg)