by Gideon Marcus

Not with a Bang

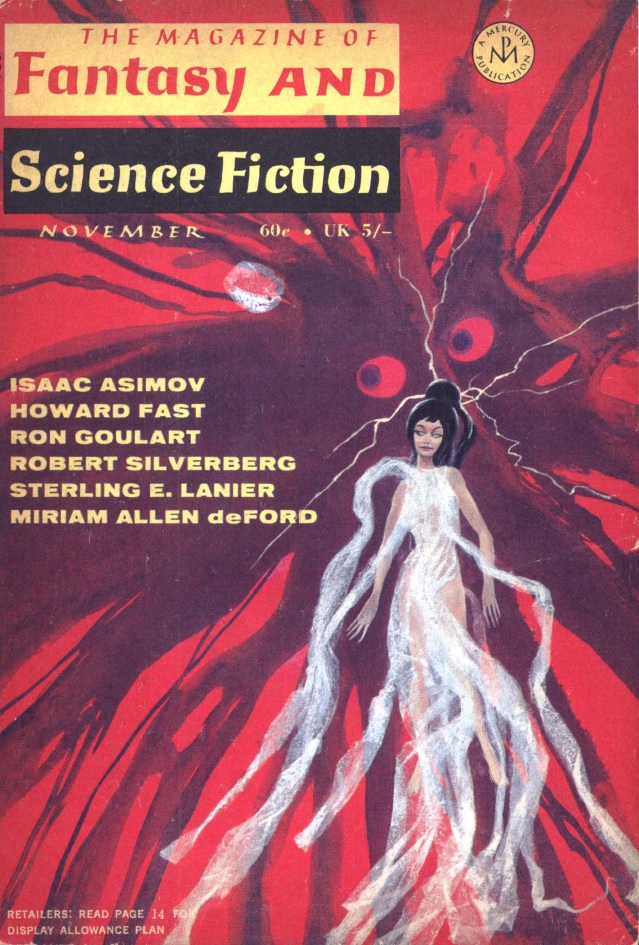

A rising tide floats all boats, but a tidal wave swamps them. 16 years ago, Galaxy magazine was the vanguard of the Silver Age of Science Fiction, along with Fantasy and Science Fiction and Astounding leading a pack of nearly forty monthly/bimonthly/quarterlies. By the end of the decade, we were down to just six mags, but the quality, by and large, was still there.

Now we're entering a new era. The number of mags is the same, but the stories are mediocre most of the time. Even the competently rendered ones feel like rehashes. In a letter I received last week, the writer said that there are yet too many outlets for the current crop of talent to supply with quality stuff.

I don't know that I agree, given that the British mags have folded and Amazing and Fantastic are mostly reprints these days. Plus, Galaxy's sister mag, Worlds of Tomorrow, has gone irregular (and Milk of Magnesia is no cure for this illness). No, I think there's some kind of general malaise in the genre. Maybe it's competition from the real world. Maybe it's higher pay-outs from the slicks.

No matter what the cause, we've got to find some way to get an influx of talent into this field. The alternative is, well, more magazines like the April 1967 issue of Galaxy.

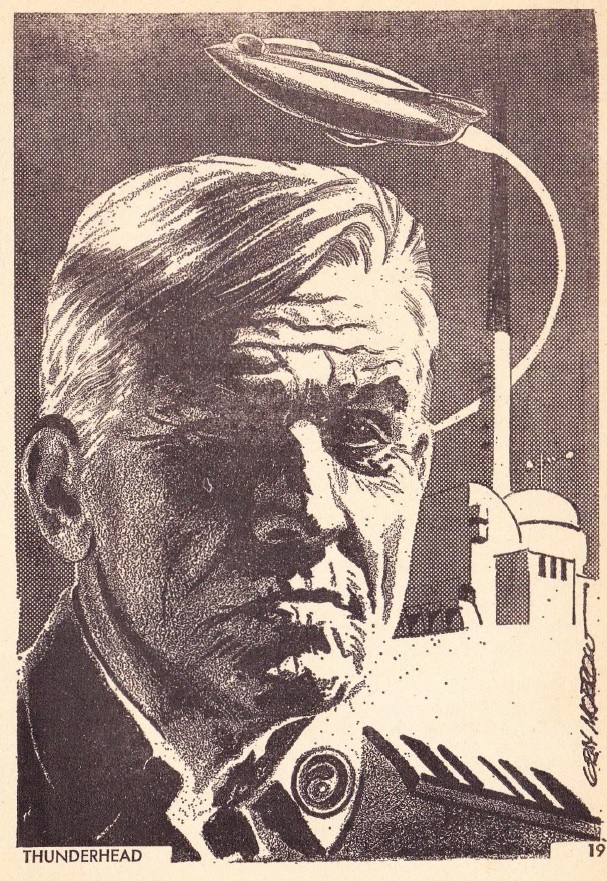

by Douglas Chaffee

A Vast Wasteland

Thunderhead, Keith Laumer

Editor Fred Pohl saved his best for first. Laumer is a competent science fiction/adventure writer when he's not writing his increasingly tired satire, and Thunderhead is nothing if not a competent science fiction/adventure.

Lieutenant Carnaby has been more than twenty years in grade, stuck on the most frontierward of planetary outposts. Indeed, it seems the Navy has forgotten all about him, since it was supposed to pick him up fifteen years ago. The world he's on has slowly decayed to one dying settlement. Yet, he remains attached to his duty, to maintain and, in an emergency, activate the beacon that will turn this rim of the galaxy into an effective defense grid.

by Gray Morrow

Said emergency occurs, with the formerly contained enemy Djann breaking out of their containment, the Terran ship Malthusa in hot pursuit. Carnaby and a young friend begin their ascent of the snowbound peak on which the beacon rests, and the story alternates between the Lieutenant, the Djann crew, and the driving Commodore of the terran cruiser.

The writing is deft, the setup interesting, and the Djann particularly interesting and innovative. On the other hand, the other characters are caricatures, and the resolution by-the-numbers.

Thus, a pleasant three stars, but no more.

Fair Test, by Robin Scott

Two aliens land on Earth to resupply with fuel and food. They are successful despite the efforts of American local law enforcement. The end of the story is a bit of social commentary as the extraterrestrials note that light meat and dark meat taste the same.

I'd have expected this story in a lesser mag, circa 1954. Not Galaxy.

Two stars.

For Your Information: The Orbits of the Comets, Willy Ley

It's no exaggeration that, for a long time, Ley's science articles were my favorite part of the magazine. They have since gotten desultory. This one, in particular, meanders all over the place and, in one particular table, is nonsensical. I suspect a misprint.

Anyway, I think this is my first two-star review for Mr Ley. It is a sad day.

The New Member, Christopher Anvil

It's also a sad day whenever Anvil's name appears in the table of contents. It has been said that one can smell an Analog reject a mile away, and the stench of this one is profound. It's about a fictional Third World island country called "Bongolia". Said nation joins the United Nations and sets about trying to make a living by extorting the richer countries as payment for centuries-old crimes against their state.

There could be a satire here, albeit not in great taste given how recent (and not very well handled) decolonization has been. Instead, it's just a bunch of unfunny cheap shots.

One star.

The Young Priests of Adytum 199, James McKimmey

Forty young men and women, the last survivors of a nuclear war, live in a coddled paradise in one of the many American shelters. They do little more than eat and mate, save for the one oddball, Peter the Funny, who prefers the clarinet. He comes to a sticky end for his noncomformity.

I guess the moral is "Never Trust Anyone Under 30". Two stars.

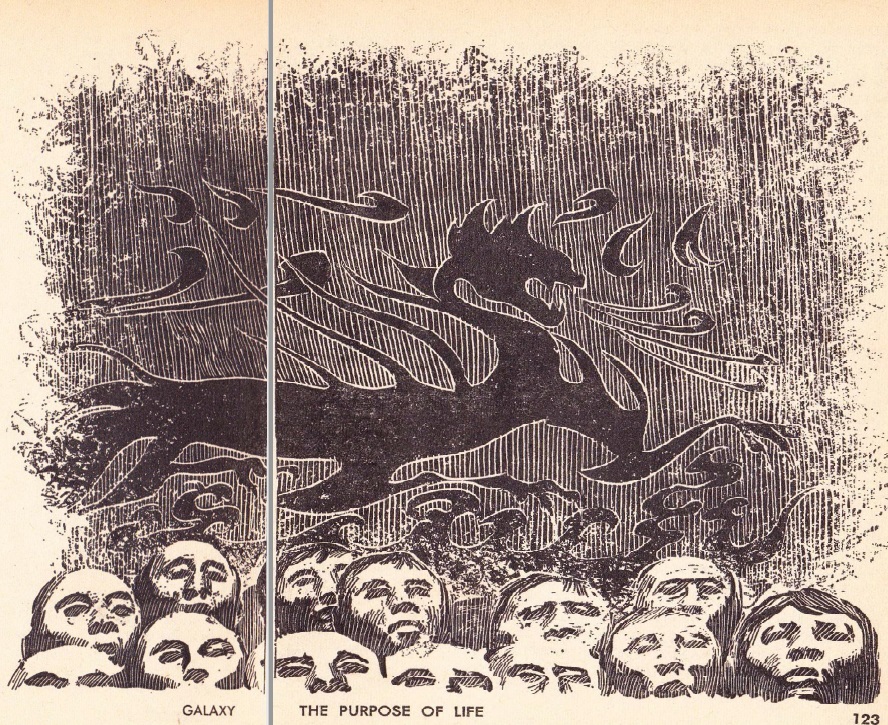

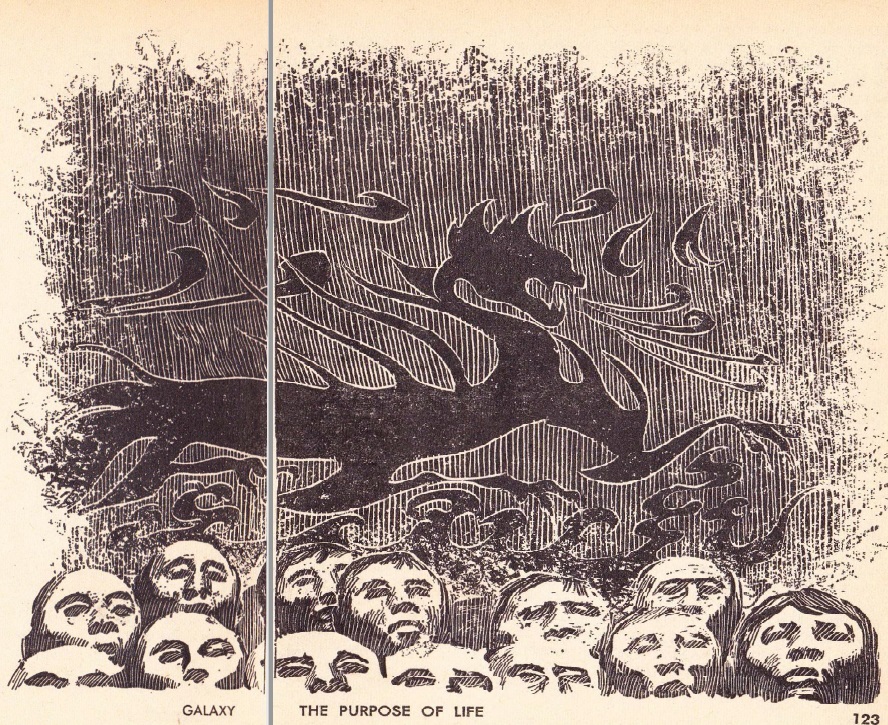

The Purpose of Life, Hayden Howard

Could it be? Have we finally reached the last chapter in the sage of the Esks?

For the past year (or has it been two, already?) we have been following the viewpoint of Dr. Joe West, an ethnologist sent out in the 1960s to do a survey on Eskimos in the Canadian North. There he discovered a new race of beings, an unholy hybrid of human and alien. They look like Eskimos, but their pregnancies last but a month, and their children mature in just a few years. These "Esks" quickly supplant their human cousins and threaten to outrun their food supply. Luckily, the bleeding hearts of the world recognize the Esks as fully human and open their doors and purses to succor them.

West, unable to convince governments of the Esk threat, unsuccessfully tries to sterilize the half-aliens with a disease of his own devise, but only succeeds in killing a few innocent humans. He is then locked up in a padded cell, then put to sleep for fifteen years. When he is awoken, he is dispatched to mainland China by the CIA. Aided by telepathic control devices implanted in his legs, he is emplaced close to the Communist leader, Mao III, whose brain he takes hold over–for purposes unknown to Dr. West. So begins the latest and longest installement.

This bit takes place on an Earth whose societies are already being rocked by Esk overpopulation. In China, the few hundred relocated to the barren hillsides two decades ago now number more than a billion. The vast Communist land is suffering the least ill effects thus far, as the import labor has produced a terrific farm surplus and as yet is not integrated with Chinese society. In America, however, every household has an Esk slave…er…servant, a situation which cannot last much longer as the subordinate race will soon vastly outnumber the master. In Canada, civilization has collapsed, and the cities are populated by starving bands of Esks.

None of this seems to bother the Esks, who endure everything with endless patience and joy. They know that someday, "the Great Bear" will return to take them all back to the sky. Such is imprinted on their racial memories.

by Jack Gaughan

In China, Mao III's generals revolt, sealing the invalid leader in a mountain redoubt-cum-tomb along with his controller, Dr. West. All efforts to curtail the Esk population so as not to outstrip the food supply meet with failure. Only one option is left — to impress the hybrids into an operation to dig the thousands of feet through solid rock to the surface.

But there is a spark of anticipation in the air. Will the Great Bear arrive before the Esks liberate themselves from their underground prison? And if so, what will happen if they arrive at the surface with their brethren all departed?

It's really hard to properly rate this segment, and the series as a whole. The premise is dumb, the conclusion rather vague and dissatisfying, and for the most part, Dr. West is either ignored or ineffectual, or both.

Yet, damned if I didn't find myself vaguely looking forward to this chapter. Damned if I didn't read the current installment in one sitting despite having resolved to take a nap instead (I do like my naps).

And damned if I didn't spend way longer on this review than I'd intended.

Call it 3 stars for this chapter and 2.5 for the whole thing. I'm not sorry I read it, but I'm glad it's over.

Within the Cloud, Piers Anthony

I think this is the first solo piece by Mr. Anthony. The premise of this vignette is that the faces we see in the clouds are actually faces, and they have something to say.

Trivial stuff. Two stars.

Ballenger's People, Kris Neville

An insane fellow, whose fragmented mind is under the delusion that it is a polity of many parts rather than a single entity, becomes homicidal when threatened by "other nations" (i.e. other human individuals).

It started promisingly, but didn't really go anywhere. Two stars.

You Men of Violence, Harry Harrison

Finally, a tidbit from a fellow whose work I often confuse with Keith Laumer's. A pacifist on the run from military types figures out how to kill without being the killer.

Rather obvious and somewhat pointless. Two stars.

Gasping for breath

Wow. That wasn't very good, was it? And with one of Pohl's major talents, Mr. Cordwainer Smith, gone to the ages, we really don't have much to look forward to. At least until Messrs. Niven and/or Vance return.

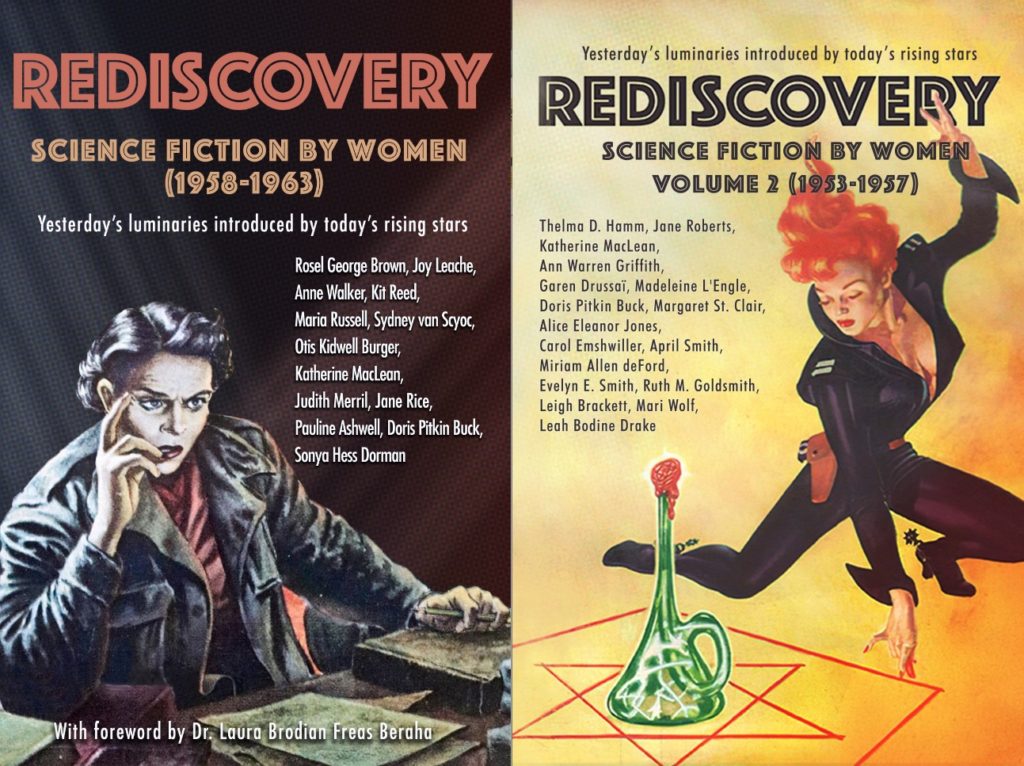

Or Pohl finds some new talent. Maybe there's a large, mostly untapped demographic he could plumb…

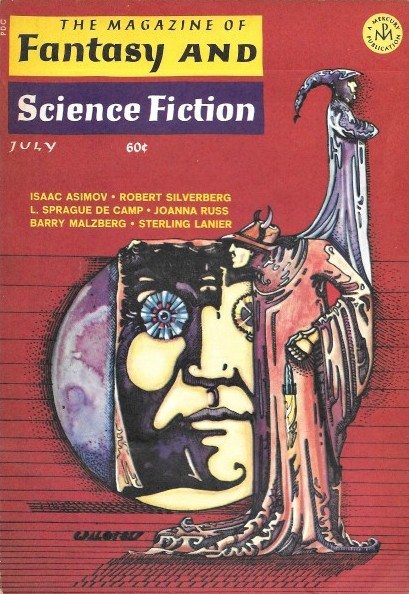

![[June 24, 1970] In love with "Ishmael in Love" (July <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/700624fsfcover-409x372.jpg)

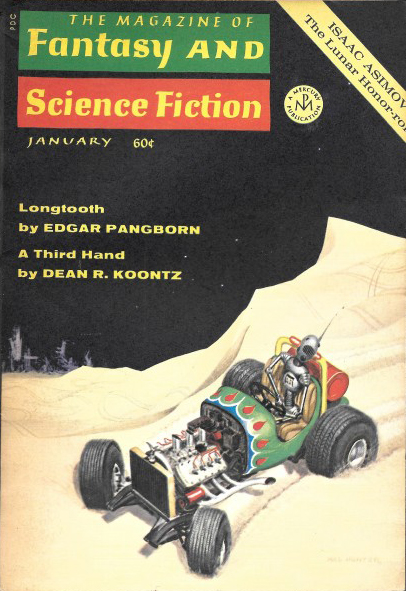

![[December 20, 1969] Stars above, stars at hand (January 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/691220fsfcover-406x372.jpg)

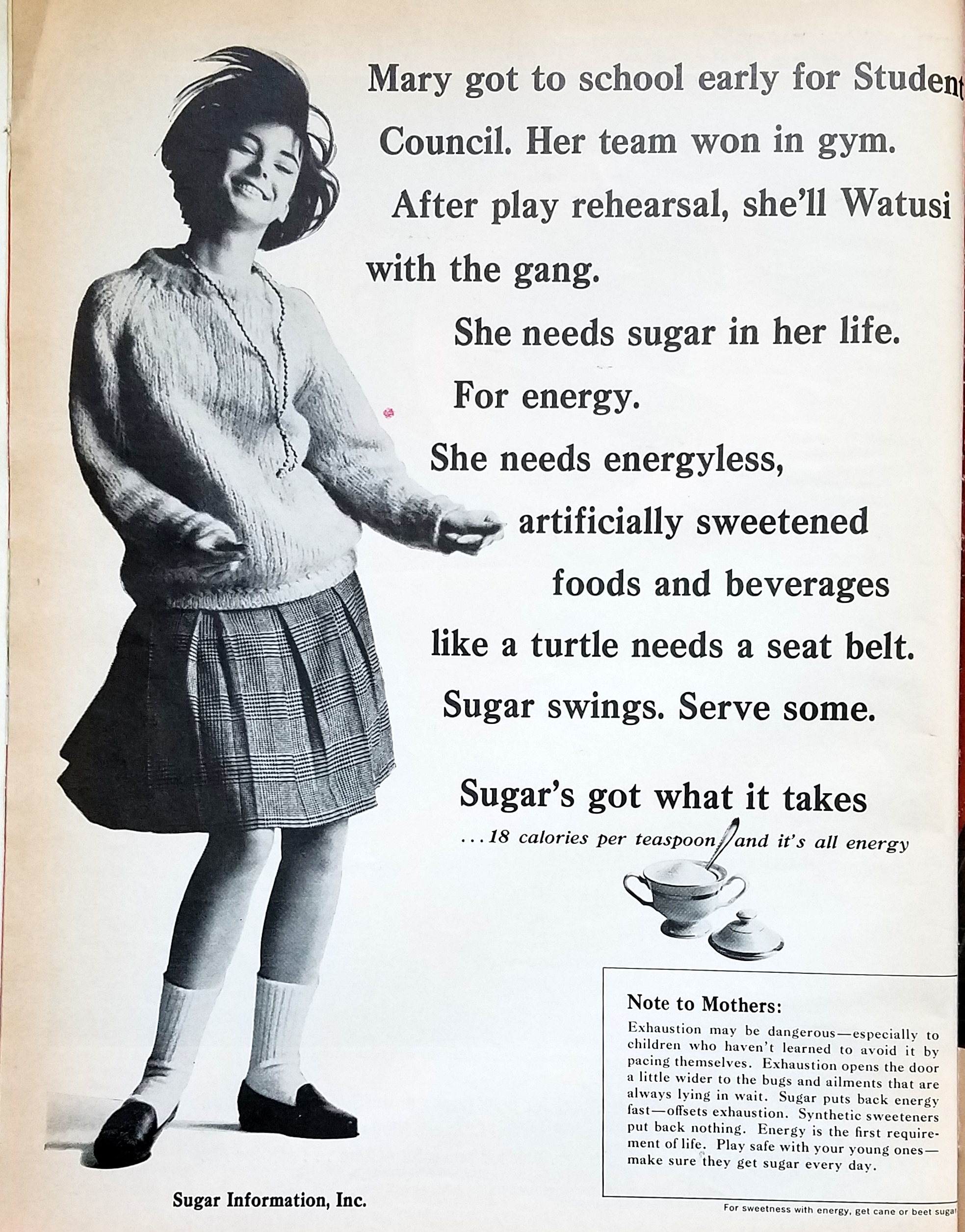

![[October 24, 1969] How sweet it isn't (November 1969 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/691024fsfcover-639x372.jpg)

![[March 10, 1967] Mediocrités, Slayer of Magazines (April 1967 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670310cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 12, 1966] A Family Tradition (December 1966 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/661112cover-469x372.jpg)

![[July 20, 1966] An Endless Summer (August 1966 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/660720cover-672x372.jpg)