by Cora Buhlert

A New President

West Germany has a new president, the seventy-year-old Social Democrat Gustav Heinemann, who up to now was secretary of justice in the grand coalition cabinet. Heinemann was elected with the narrowest of majorities, beating his conservative opponent by only six votes.

The West German president is mainly a ceremonial figure; he has very little political power. The president is also elected by the members of the West German federal and state parliaments rather than the people. Apparently, we cannot be trusted to elect our own president, because our parents and grandparents elected Paul von Hindenburg more than forty years ago.

But even though I had no chance to vote for Gustav Heinemann, I welcome his election, because I've come to know Mr. Heinemann as a highly principled politician who stands for peace and justice and opposed the rearmament of West Germany.

In his first speech after his election, Gustav Heinemann promised that he wanted to be a president for the people, even if the people did not get to elect him. Personally, I believe that he is exactly the right president for these difficult times.

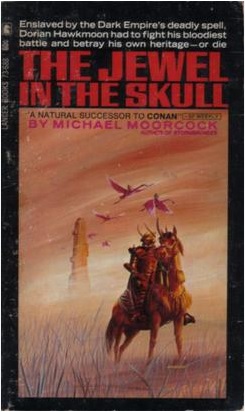

More than just Conan

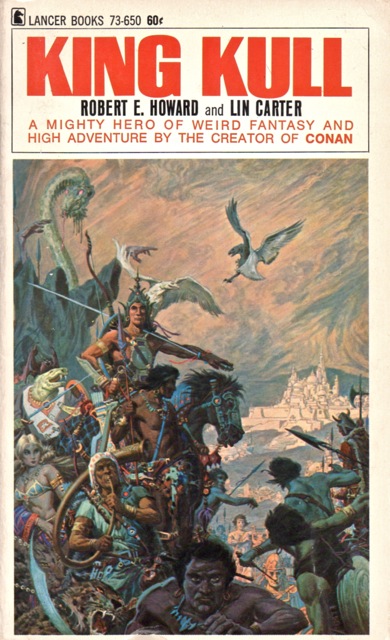

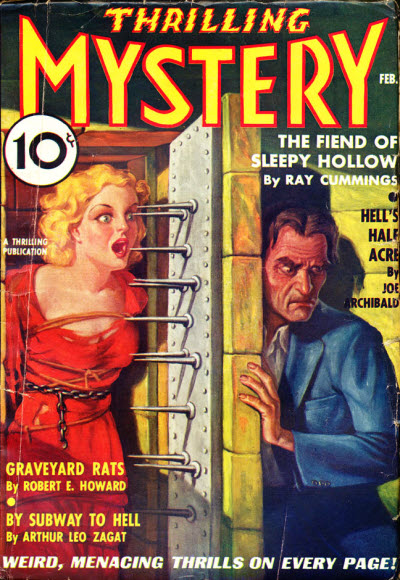

When Lancer started reprinting the adventures of Conan the Cimmerian three years ago, exactly thirty years after Robert E. Howard's untimely death, they not only pushed the already simmering revival of the genre Fritz Leiber called sword and sorcery into overdrive, but also opened the floodgates for other vintage fantasy stories and novels to come back into print.

No longer do you have to sift through the crumbling pages of Weird Tales or Unknown or pay extortionate prices for Gnome Press or Arkham House hardcover reprints to track down an early adventure of Conan or Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. On the contrary, the heroes of yesteryear are right there in the spinner rack of your local newsstand, gas station, grocery store or bookstore, sporting striking covers by talented artists like Frank Frazetta or J. Jones. The sword and sorcery revival has truly been a boon for fans of vintage weird fiction.

Among the authors of yesteryear coming back into print is none other than Robert E. Howard himself. For while Howard will probably always be associated with Conan first, he was extremely prolific, penning more than two hundred stories in various genres in his short life. In this article, I want to take a look at some of the other Robert E. Howard heroes whose adventures you can find on the shelves right now.

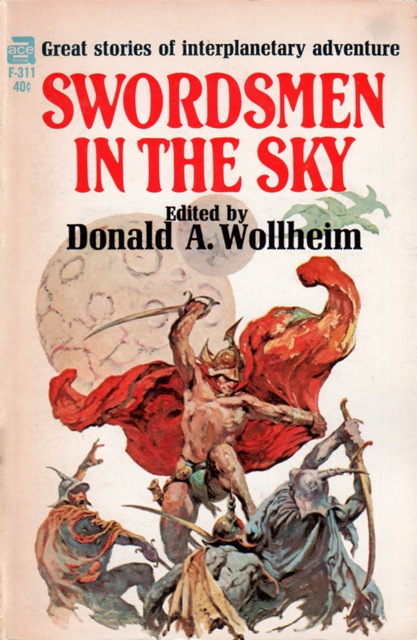

The Philosophical Atlantean: King Kull

Spurred on by the success of their Conan reprints, Lancer made a foray into the rest of Howard's oeuvre and reprinted the adventures of Howard's other Barbarian hero, Kull of Atlantis.

Like Conan, Kull is a wandering adventurer who winds up becoming king of the civilised kingdom of Valusia after slaying the previous ruler. Kull only appeared in two stories in Weird Tales, though the ever enterprising L. Sprague de Camp found several unpublished and sometimes unfinished Kull stories in Howard's trunk (and I have it on good authority that it really is a trunk), had Lin Carter finish the incomplete stories and assembled King Kull.

Because of his superficial similarities to the Cimmerian Barbarian, Kull is considered a prototype Conan. But that would be unfair, because even though they are both adventurers turned kings, Kull is a very different character from Conan, quieter, more introspective, more philosophical, more – dare I say it – gullible.

The Conan stories cover the entire spectrum of Conan's career, from teenaged thief to middle-aged king. The Kull stories, on the other hand, focus almost entirely on his time as King of Valusia – with one exception. Because for Kull we get something we never got for Conan: the story of why he left his home Atlantis in the first place. And no, it's not for the reason you think.

"Exile of Atlantis" introduces us to a teenaged Kull, an outsider adopted into a tribe of Atlantean barbarians. Most of the story is given over to a hunting expedition as well as a dream sequence, where Kull sees his future as king. But what spurs Kull into leaving home is seeing a young woman from his village about to be burned at the stake for daring to fall in love with a Lemurian pirate. Kull is disgusted by this and mercy-kills the woman before the flames can reach her. Then he flees, pursued by furious tribespeople.

"Exile of Atlantis" was never published during Howard's lifetime and it's easy to see why—it's more vignette than story. But it does set the tone for the adventures that follow and introduces Kull both as a perpetual outsider as well as someone who is willing to question and defy tradition, if necessary. Finally, forbidden love as well as Kull's firm believe that love should trump tradition, custom and law is a recurring theme throughout the stories, as Kull helps several young couples to get together with their one true love, against legal and parental opposition.

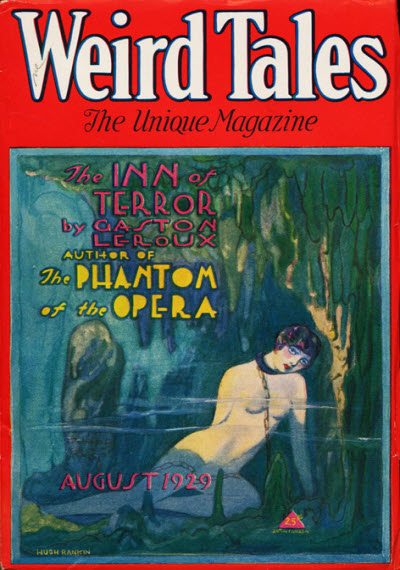

"The Shadow Kingdom" was the first of the two Kull stories published during Howard's lifetime in the August 1929 issue of Weird Tales and very much sets the stage for what is to follow. The story introduces us to King Kull, as he is watching a parade in his honour, while musing about identity, the nature of reality and the great questions of life.

However, Kull has more immediate problems to deal with, because the Pictish ambassador, Ka-nu the Ancient, warns him of a conspiracy in his own court and sends one of his warriors, Brule the Spear-Slayer, to aid and protect Kull. Those who have read the Conan stories have encountered the Picts before. Based on the ancient inhabitants of Scotland, the Picts reoccur throughout Howard's work, though Howard's Picts bear no resemblance to their historical counterparts.

Kull is initially irritated by Brule, who seems to know the royal palace better than Kull himself. But the two men quickly become fast friends, when Brule informs Kull that an ancient pre-human race of shapeshifting Serpent Men has invaded the kingdom and the royal palace and are quietly replacing guards, courtiers and councillors and are planning to murder and replace Kull, too.

"The Shadow Kingdom" is a chillingly paranoid story reminiscent of John W. Campbell's "Who Goes There?" and the 1956 movie Invasion of the Body Snatchers, though it predates both. Apparently, there are folk who believe that the Serpent Men from "The Shadow Kingdom" really existed and still exist today, similar to how some people believed that the Shaver Mysteries which infested Amazing Stories some twenty years ago were real.

After their ordeal in "The Shadow Kingdom", Brule remains Kull's constant companion and frequently has to rescue his friend from conspirators and assassins as well as from Kull's own gullibility and tendency to get lost in his thoughts. In "The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune", the only other Kull story published during Howard's lifetime, Kull becomes fascinated with the House of Thousand Mirrors inhabited by the wizard Tuzun Thune and keeps gazing into those mirrors, wondering whether he is real or merely a mirror image himself. Just as Kull is about to be sucked into the mirror completely, Brule appears, kills the wizard and smashes the mirrors.

"The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune" will seem familiar to anybody whose ever visited a hall of mirrors at a fun fair or carnival. The story "Delcardes' Cat" also clearly appears to be inspired by travelling fun fairs and fraudulent sideshow attractions. This time around, Kull becomes fascinated with Saremes, an ancient and wise talking cat owned by the noblewoman Delcardes who asks Kull's permission to marry a commoner. Kull has deep and philosophical discussions with Saremes and never once wonders why this regal feline is always carried around by the masked slave Kuthulos.

Things come to a head, when Saremes informs Kull that his friend Brule is in danger and that Kull must dive into a lake inhabited by an ancient amphibian race to rescue him. Brule, however, is not in danger, but once again has to rescue Kull from a plot by his archenemy, the skull-faced wizard Thulsa Doom. As for the cat, she may be wise and ancient and beautiful, but she obviously cannot speak. Instead, her voice was provided by the masked slave Kuthulos. It's easy to imagine Howard witnessing a similar performance in a small carnival somewhere in rural Texas in his youth.

"By This Axe I Rule!" features yet another plot against Kull, instigated by disgruntled noblemen and a rabble-rousing poet. Kull himself, meanwhile, is depressed that some people still mourn the tyrannical king Borna whom Kull slayed and replaced and that even the Cult of the Serpent Men still has worshippers. Kull is also frustrated that even as king he is still constrained by the ancient laws of Valusia, such as a law which forbids free men to marry slaves, even though a young nobleman petitions Kull to allow him to wed the slave girl Ala with whom he has fallen in love. Not long thereafter, Kull meets Ala herself and confesses to her that even as a king, he is still slave to Valusia's cruel ancient laws.

The conspirators strike that night and invade Kull's bedchamber. Kull fights them off with battle axe, but there are too many of them. However, he is saved in the nick of time, because Ala overheard the plot against the king and sounded the alarm. Grateful, Kull takes his battle axe to smash the stone tablets containing Valusia's outdated laws and declares that he is the law now. Then he personally sees to it that Ala and her lover are allowed to marry.

If "By This Axe I Rule!" seems a little familiar, that's maybe because it is. For after the story failed to sell, Howard rewrote it as "The Phoenix on the Sword", the story which introduced Conan the Cimmerian to the world. But while "The Phoenix on the Sword" is a great story, I still prefer "By This Axe I Rule!" because the touching love story between Ala and the young nobleman and the scene of Kull taking his battle axe to the outdated laws of Valusia are sadly absent from the Conan story.

It is notable how many of the Kull stories are concerned with forbidden love and how Kull is clearly frustrated by outdated marriage laws keeping lovers apart until he literally smashes those laws to pieces. Considering that the US Supreme Court struck down state laws forbidding mixed race marriages in several southern states only two years ago (not using a battle axe), I for one can only cheer on Kull and his creator.

But while there is a lot of romance in the Kull stories, Kull himself has no romantic entanglements with women – very much unlike Conan – and even muses at one point that the love of a woman is not for him. One can see homoerotic undertones in Kull's relationship with Brule, though Howard could not clearly spell this out in the late 1920s. Or maybe Kull just prefers celibacy.

It may be blasphemy, but I prefer Kull to Conan. Everybody who enjoys the adventures of the Cimmerian Barbarian should pick up King Kull.

Five stars.

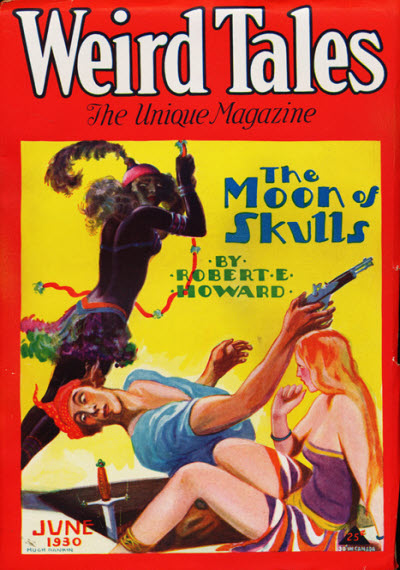

The Avenging Puritan: Red Shadows

Another Robert E. Howard character who predates Conan is Solomon Kane, a sixteenth century Puritan who is on a mission from God (or so he believes) "to ease evil men of their lives". The idea sounds fascinating, but once again the Solomon Kane stories are only found in forty-year-old issues of Weird Tales and have never been reprinted. Until now.

Luckily, my friend Bobby, who shares my interest in the works of Robert E. Howard and other Weird Tales authors of yesteryear, sent me a copy of Red Shadows, a collection of all the Solomon Kane stories, including those that were never published and sometimes not even finished during Howard's lifetime. Red Shadows is a hardcover volume with interior illustrations by J. Jones published by the small press Donald M. Grant Publisher Inc. which also published two collections of Howard's humorous westerns about a very big, very strong and not very bright hillbilly named Breckenridge Elkins and his chaotic family. Sadly I don't own either of those.

The Solomon Kane stories, however, are excellent, mixing historical adventure of the sort that used to be found in the pages of the pulp magazine Adventure with horror elements. Unlike with Kull, we never learn why Solomon Kane does what he does. There are hints, particularly in the poems included in the collection, that Kane was always a violent man and sailed with Sir Francis Drake, but we never learn how Solomon Kane came by his strong religious convictions or how he came to believe that he is on a mission from God.

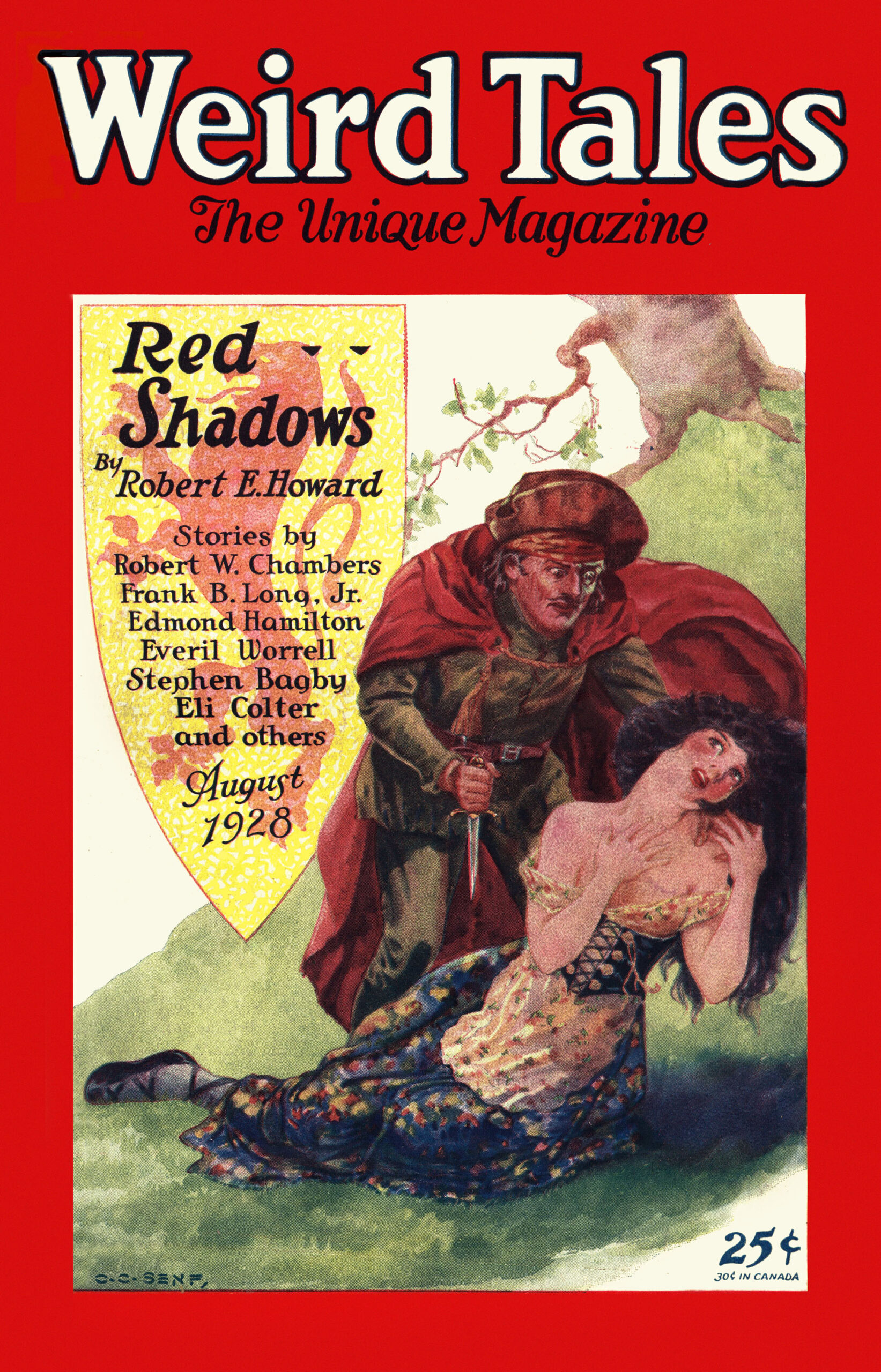

Early stories show Solomon Kane wandering around England and later the Black Forest in Germany, tangling with pirates and observing several cases of vengeance from beyond the grave. These are fine adventure stories and suitably spooky gothic morality tales. But then Solomon Kane's wanderings literally take him into the heart of darkness with the novelette "Red Shadows", first published in the August 1928 issue of Weird Tales.

"Red Shadows" begins in France, where Solomon Kane finds a mortally injured young woman by the side of the road and comforts her as she dies. Before she draws her final breath, the woman tells Kane that she was assaulted and left for dead by a bandit named Le Loup. "Men will die for this," Kane vows darkly and embarks onto a hunt for Le Loup and his associates which will take him several years and across the world.

Kane finally tracks down Le Loup in a village in the darkest heart of Africa. When the opponents finally come face to face, Le Loup asks Kane whether the woman he murdered was Kane's bride, wife, or sister and is stunned when he learns that Kane had never met the young woman before that fateful day.

In the course of "Red Shadows", Kane also meets and befriends N'Longa, an African shaman, a so-called juju man. Though a sympathetic character, N'Longa initially appears to be an outdated and racist stereotype speaking broken English. However, as Solomon Kane and N'Longa share further adventures, it gradually becomes clear that N'Longa is much more than a mere stereotype. Not only is his magic real, he is also clearly the smartest person in the Solomon Kane stories. Indeed, N'Longa even calls out Kane on his prejudices at one point. Finally, N'Longa also gives Kane a magical weapon, an ancient juju staff, which turns out to be the biblical Staff of Solomon, now wielded by his latter day namesake.

Pulp fiction set in Africa is often full of offensive and downright racist caricatures. Howard does not completely manage to avoid these pitfalls, when describing Kane's wanderings through Africa, encountering vampires, harpies, hidden cities and monsters sealed away in ancient tombs. However, it is also notable that Solomon Kane himself makes no racial distinctions between the people he helps and is as willing to save an angelic blonde English girl from being sacrificed to an ancient god as he is to protect an African village from winged monsters and liberate African slaves from their Arab captors.

During his wanderings through Africa, we also see Kane's religious convictions gradually crumbling. As a devout Puritan, he initially abhors magic, but he also sees that N'Longa's magic, though not even remotely Christian, is nonetheless a force for good as is the Staff of Solomon, which predates both Judaism and Christianity.

Solomon Kane is a complex and fascinating character. He has the religious zeal of Witchfinder General Matthew Hopkins, memorably portrayed by Vincent Price (who would be perfect to play Solomon Kane) on film last year, only that he is a heroic figure, whereas Hopkins is the darkest of villains.

Gothic horror at its very best.

Five stars.

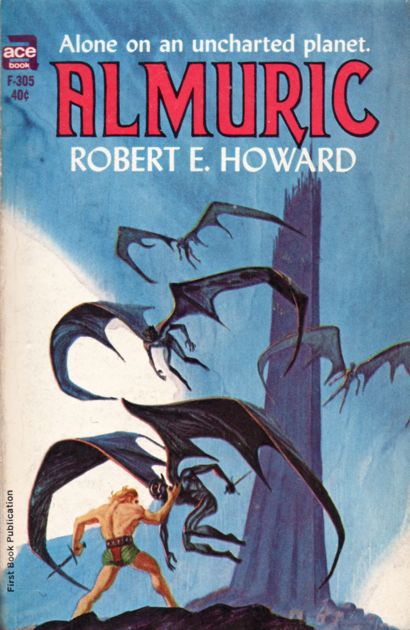

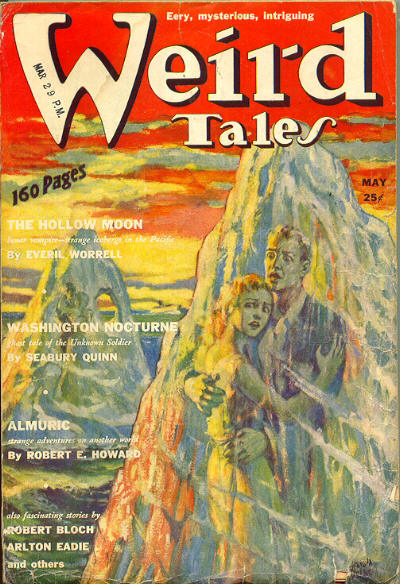

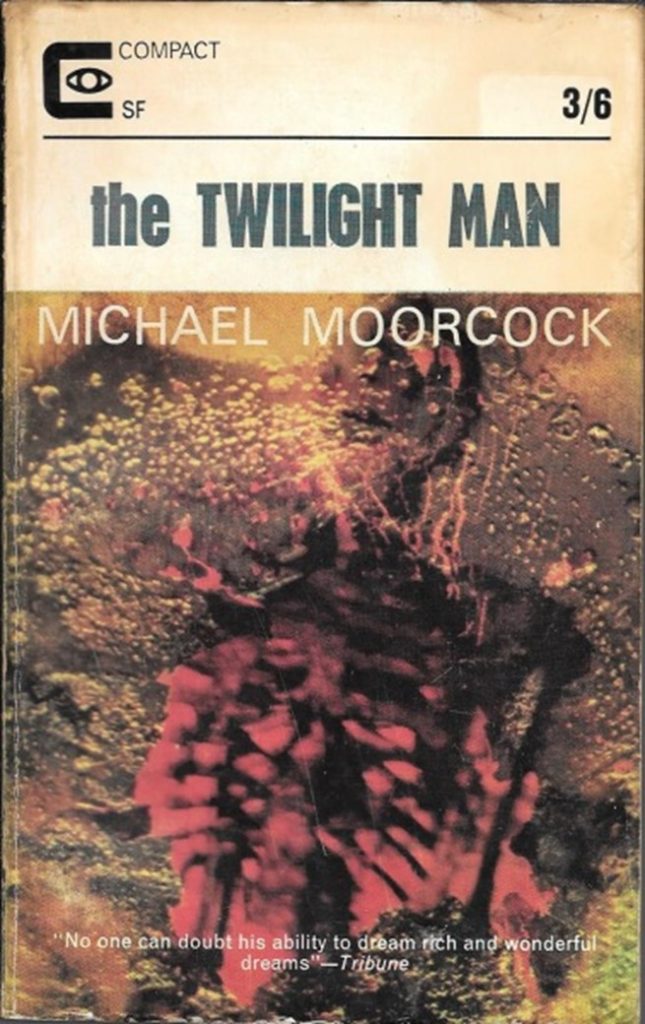

The Time and Space-Displaced Fugitive: Almuric

Almuric is an oddity even for Robert E. Howard's extremely varied oeuvre. It's his sole foray into Burroughs style planetary romance and one of only two novels Howard wrote. Almuric was serialised posthumously in Weird Tales from May to August 1939 and reprinted by Ace in 1964.

Taking his cue from Burroughs' Barsoom novels, Almuric opens with a framing story. The scientist Professor Hildebrand recounts his meeting with Esau Cairn, whom the Professor describes as "definitely not a criminal", but "a man born in the wrong time". Cairn stumbles into Hildebrand's observatory while on the run for murdering the corrupt politician Boss Blaine (don't worry, he had it coming), the police hot on his heels. Cairn is determined to go down fighting and die in a shootout with the police just like Bonnie and Clyde, who to Howard were not just the subject of a popular movie, but outlaws who operated in his home state of Texas and were shot dead not far from his hometown Cross Plains. Luckily, Professor Hildebrand has a better idea and uses a machine he invented to teleport Cairn to the planet Almuric.

Once there, Cairn takes over as the narrator and has the sort of adventures you would expect from a Burroughs style planetary romance. He encounters the local wildlife as well as a species of ape men named the Guras. After putting his boxing skills to good use and proving his mettle, Cairn is adopted into a tribe of Guras and falls in love with Athla, daughter of the chief. Lucky for Cairn, female Guras look like regular human women.

More adventures follow, as Cairn is captured by a rival tribe, has to fight various monsters and must rescue Athla from a species of winged humanoids called the Yagas whose queen Yasmeena not only has carnal designs on Cairn, but also wants to sacrifice Athla to her gods.

In theory, Robert E. Howard would seem to be the perfect writer for a Burroughs style planetary romance. In practice, however, Almuric is the weakest work by Howard I've read so far. The novel feels choppy and disjointed and there are lengthy passages where Cairn gives us all sorts of information about the world of Almuric and its inhabitants. This is very uncommon for Howard who normally doesn't resort to lengthy encyclopaedic descriptions, but integrates the information into the plot. It almost feels as if Howard's private notes about the world of Almuric, similar to "The Hyborian Age" essay which details the world of Conan, had somehow ended up in the novel itself.

So why is Almuric so different from Howard's other works? The answer is simple. Almuric was published posthumously and very likely remained unfinished at the time of Howard's death and was completed by another writer. We do not know who this writer was, since Weird Tales does not credit them. A likely suspect is fellow Weird Tales author as well as Howard's literary agent Otis Adalbert Kline, who penned several planetary romances himself. Alas, Kline died in 1946, so we will never know for sure.

Even a weak novel by Robert E. Howard is still better than those by many other writers at their best.

Three and a half stars.

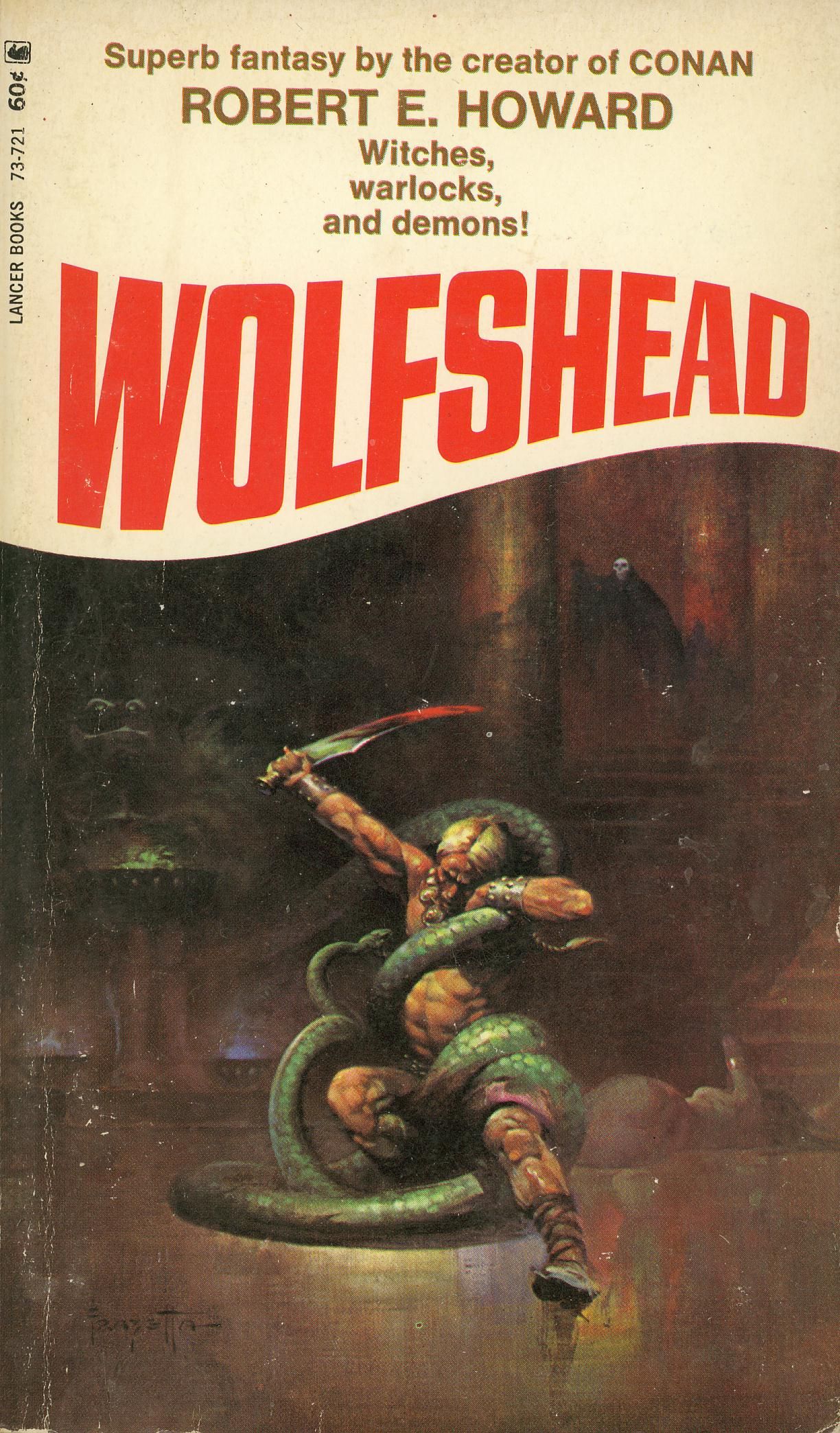

Lovecraftian Terrors: Wolfshead

Following the success of their Conan reprints, Lancer is gradually branching out into other works by Robert E. Howard and brought us not only King Kull, but also Wolfshead, a collection of seven horror stories by Robert E. Howard with a striking cover by Frank Frazetta.

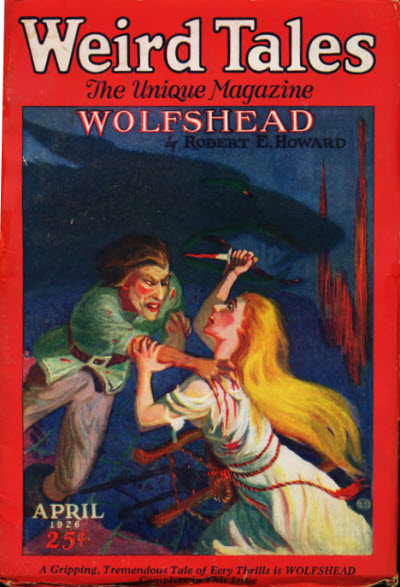

Unsurprisingly, the titular story, which appeared in the April 1926 issue of Weird Tales, published when Howard was only twenty years old, is a werewolf story and apparently the sequel to another story, which Lancer in their infinite wisdom chose not to include. "Wolfshead" is not a bad story by any means, though very much the work of a beginning writer.

In "The Horror From the Mound", first published in the May 1932 issue of Weird Tales, Howard puts his unique spin on that other classic monster of modern horror, the vampire. However, his vampire is not residing in a coffin in the bowels of a castle in Transylvania, but much closer to home (at least from Howard's point of view) in an Indian burial mound in Texas, which a white rancher unwisely disturbs after having been warned not to do so by his Mexican neighbour.

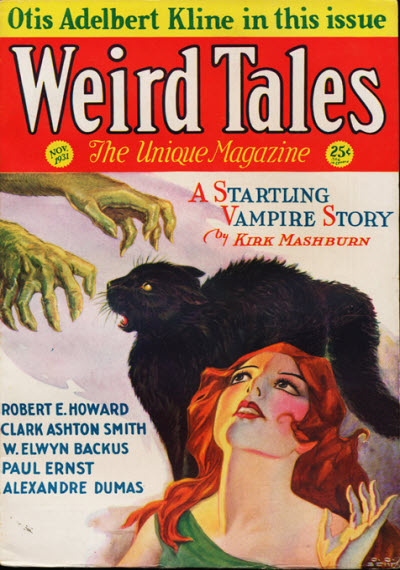

The remaining stories are clearly influenced by H.P. Lovecraft and his Cthulhu Mythos and feature mysterious tomes of black magic and unspeakable monsters from beyond. The Lovecraft influence is not that surprising, since Lovecraft and Howard did not just both write for Weird Tales, but were also pen pals who kept up a voluminous correspondence, much of which apparently survives and will hopefully see print someday.

But even though they influenced each other, Robert E. Howard was a very different writer than H.P. Lovecraft and also brings a very different sensibility to his stories. For while Lovecraft's protagonists tend to be driven mad by their encounters with the unspeakable, Howard's protagonists usually fight the monster or die trying, though the poet Justin Geoffrey, protagonist of "The Black Stone", does go mad after an encounter with a cursed stone, an unspeakable cult and a terrifying monster.

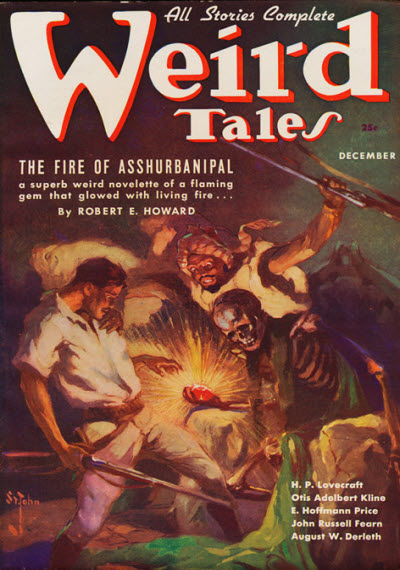

Howard's stories also have a wider range of settings from Texas via Ireland, France and Hungary all the way to Middle East, which is the setting of "The Fires of Asshurbanipal", which combines Lovecraftian horror with the high adventure of the Conan stories.

"The Valley of the Worm" and "The Cairn on the Headland", include two more subjects that are dear to Howard's heart, reincarnation and Norse mythology. "The Valley of the Worm" features James Allison, a terminally ill man on his deathbed, remembering a previous life as Niord, a Norse tribesman who fights a giant snake in a scene strikingly illustrated by Frank Frazetta on the cover and later takes his revenge on a monstrous Lovecraftian entity that slaughtered his tribe. The Picts, another subject that clearly fascinated Howard judging by their repeated appearances in his stories, also show up. Apparently, Howard wrote several stories about James Allison remembering his past lives and I hope that all of them will eventually see print again.

"The Cairn on the Headland" is set in Ireland, where the two-fisted scholar James O'Brien not only relives the Battle of Clontarf in 1014 AD, in which he took part in a previous life as the Irish warrior Red Cumal, but also has to save Ireland from the wrath of the Norse god Odin who took part in said battle disguised as a Viking chieftain and lies buried in the titular Cairn, which O'Brien's villainous companion unwisely disturbs. Howard has Irish ancestry and was clearly fascinated by the history and mythology of his forebearers.

Wolfshead includes but a small selection of the many horror stories that Howard wrote, but it also offers a taste of how varied Howard's works were. I hope that this is but the first of many collections of Robert E. Howard's horror stories to come.

A great and varied horror collection by a true master of the genre.

Four and a half stars.

There's Gold in Them Pulps and in That Trunk, Too: Other Howard works we may hopefully see again soon

The untimely death of Robert E. Howard is one of the great tragedies of our genre. Whenever I read a Howard story and marvel at what a great writer he was, I also mourn all the stories he never got to write, all the tales that remain untold. Howard pivoted to the more lucrative western market towards the end of his life, but would he have returned to Conan or even Kull or Solomon Kane later in life, just as his nigh contemporary Fritz Leiber keeps returning to Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser? We will never know.

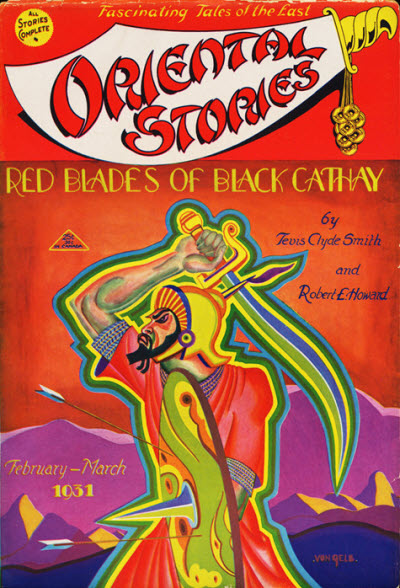

However, the success of the Conan reprints is giving us the chance to explore the rest of Howard's work. Another Howard hero, Bran Mak Morn, last king of the Picts who defends his people against Roman occupiers, is set to be reprinted later this year. There is still so much more to discover such as the tales Howard wrote for Weird Tales' sister magazine Oriental Stories and other adventure-focussed pulps like Top-Notch or Thrilling Adventure, featuring the adventures of the American treasure hunter Kirby O'Donnell and the Texan gunfighter Francis Xavier Gordon a.k.a. El Borak in Kurdistan and Afghanistan at the turn of the century. For Oriental Stories, Howard also wrote several historical stories set during the Crusades, which are allegedly excellent.

For the infamous shudder pulps, Howard penned several tales featuring the occult investigator Steve Harrison and for Weird Tales, he wrote the Fu Manchu type thriller "Skull Face". Howard also had a funny side, which is in full display in the humorous westerns featuring the big and dumb hillbilly Breckenridge Elkins as well as his stories featuring the boxing sailor Steve Costigan, which first appeared in the pulp magazine Fight Stories. I've read one of the Steve Costigan stories and it was hilarious. I hope that eventually we will get to read them all.

And then, of course, there is also Howard's trunk of unpublished stories. Who knows what gems still lurk in there?

![[March 28, 1969] Life Beyond Conan: The Other Heroes of Robert E. Howard](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/KNGKLLWGLQ1967-390x372.jpg)

![[December 16, 1967] Long Distance Travel (December 1967 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/671216covers-672x372.jpg)

![[March 16, 1967] A Matter of Life and Death (<i>Why Call Them Back From Heaven?</i> by Clifford D. Simak; <i>Tarnsman of Gor</i>, by John Norman)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670316covers-672x372.jpg)

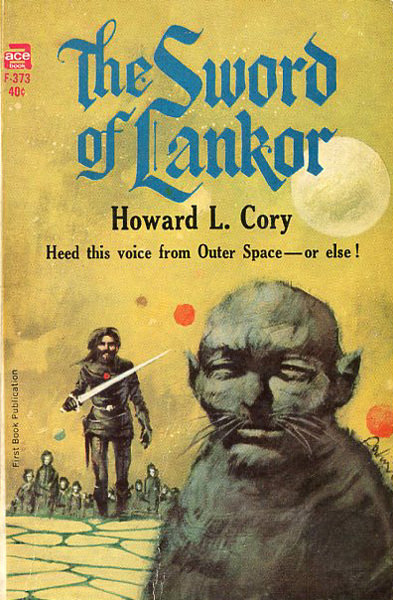

![[January 22, 1966] Monks, Demi-Gods and Cat People: <i>The Sword of Lankor</i> by Howard L. Cory](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/SWRDLNKR1966-393x372.jpg)