by Fiona Moore

1969 continues to disappoint on the genre cinema front, at least in the UK. So here we have a middling horror picture, and a very good picture which is sort of SF, if you squint at it right.

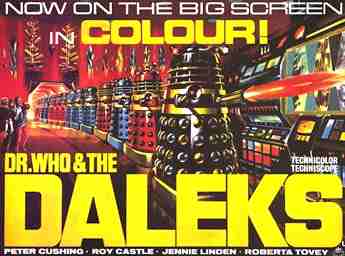

Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed

Poster for Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed

After too long an absence from Hammer, it’s good to see Terence Fisher back at the helm of another Peter Cushing Frankenstein movie. This one sees the eponymous Baron on the trail of his former assistant Brandt (George Pravda), who has been confined to a lunatic asylum somewhere in Mitteleuropa. Frankenstein plans to extract from Brandt the secret of preserving brains on ice, in a homage to Frankenstein’s conviction in the first movie that he could use his technology to indefinitely prolong the lifespans of geniuses by transferring their brains from body to body. Frankenstein inveigles his way into the lives of a young doctor at the asylum, Holst (Simon Ward), and his fiancée, Anna (Veronica Carlson), using a combination of blackmail and psychological manipulation to gain their assistance. However, Brandt suffers a heart attack, meaning his brain must of course be transferred into another person’s body (Freddie Jones), and further violence and chaos ensues.

Hammer have clearly been taking notes from the recent success of Witchfinder General (1968), as the movie’s main strength is the psychological horror of the way Frankenstein encourages his victims on to more and more awful crimes. Frankenstein’s hold over Holst is that the latter has been secretly dealing narcotics in order to pay for medical treatment for Anna’s mother, a development which speaks to contemporary concerns about the ready availability of drugs and the moral questions surrounding their use. I should also warn viewers about a graphic rape scene which just about manages to stay within the bounds of being played for horror and not titillation, but is still rather disturbing.

Peter Cushing terrifies as the sinister Baron Frankenstein

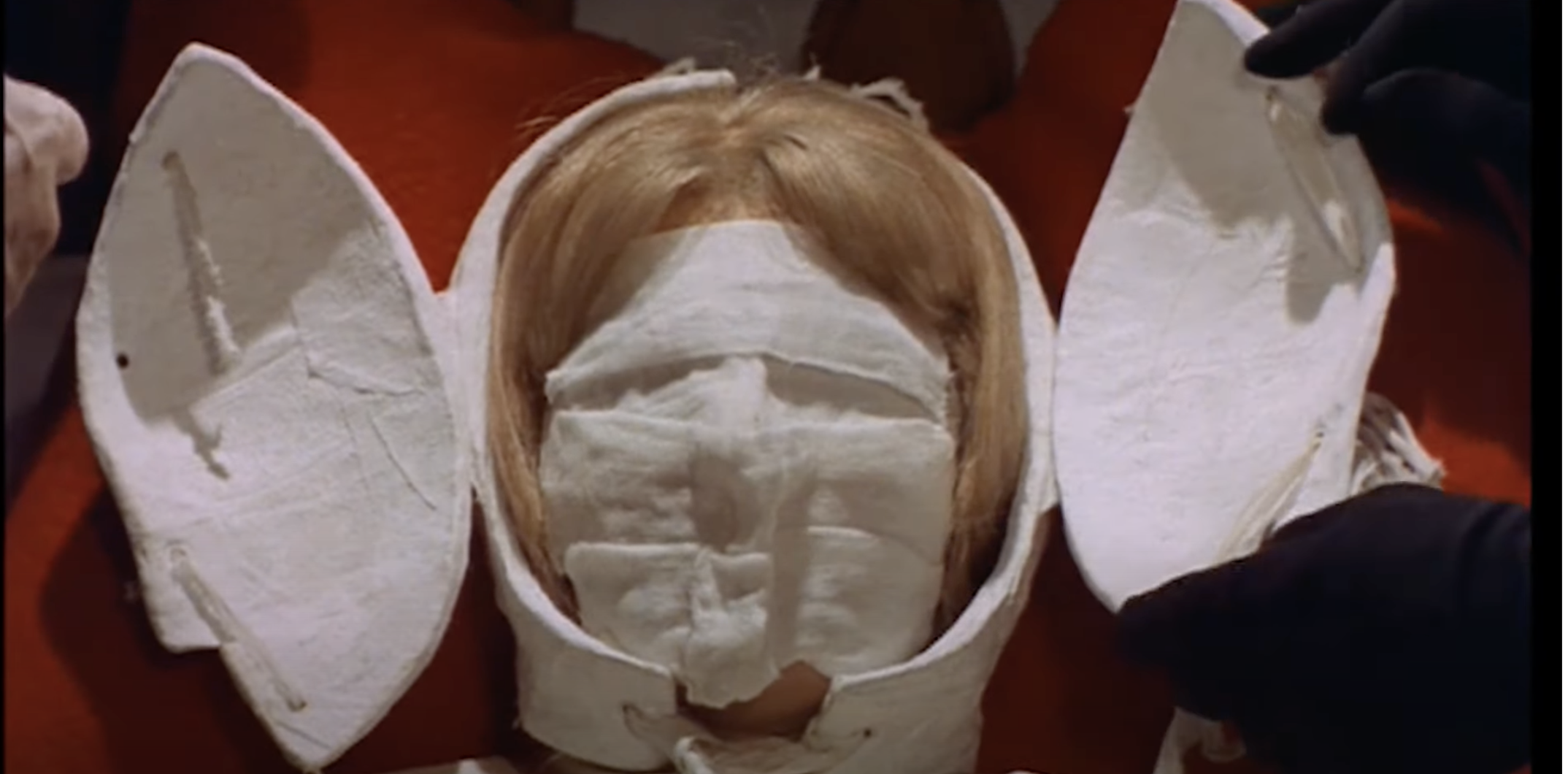

Cushing is genuinely and credibly terrifying in the title role, giving the Baron a more physical performance while retaining the psychopathic coldness and inhumanity of the previous films. Fisher retains his fondness for startling but appropriate juxtapositions, for instance following Anna’s remark to the Baron “you’ll find it very quiet here” with a cut to a screaming madwoman in the asylum. There’s a nice bait-and-switch early on regarding the Baron’s identity (and one which seems like a callback to the familiar saw about the Baron really being the monster), and we also get a suitably comic morgue attendant at one point. Production values are high for a Hammer film, with some very good creature makeup and a pyrotechnic ending.

Freddie Jones as The Creature cuts a pathetic figure

Freddie Jones as The Creature cuts a pathetic figure

Nonetheless, the movie suffers from some annoying plot holes and character contrivances, as well as an opening scene which goes nowhere and adds nothing to the plot, and a resolution which I found lacking in credibility and, indeed, closure. There are also a number of Dickensian coincidences (a doctor at the very lunatic asylum the Baron wants to get into having a fiancée who runs a boarding house, for instance), which might be forgiveable as an element of the genre but do tend to grate. I would place this as the third best of the franchise, after Curse of Frankenstein and Frankenstein Created Woman: however, in a year where decent horror movies have been thin on the ground, it’s a welcome relief. Three and a half stars.

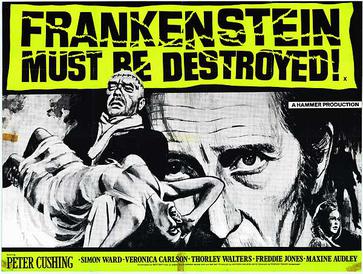

The Italian Job

Poster for The Italian Job

The Italian Job is a joyous heist comedy and a welcome counter to some of the divisive language finding its way into British social and political discourse. Britons from all walks of life—Cockneys, aristocrats, homosexuals, immigrants, professors and others—come together to pull off a clever theft and raise the proverbial two fingers to rivals on the Continent.

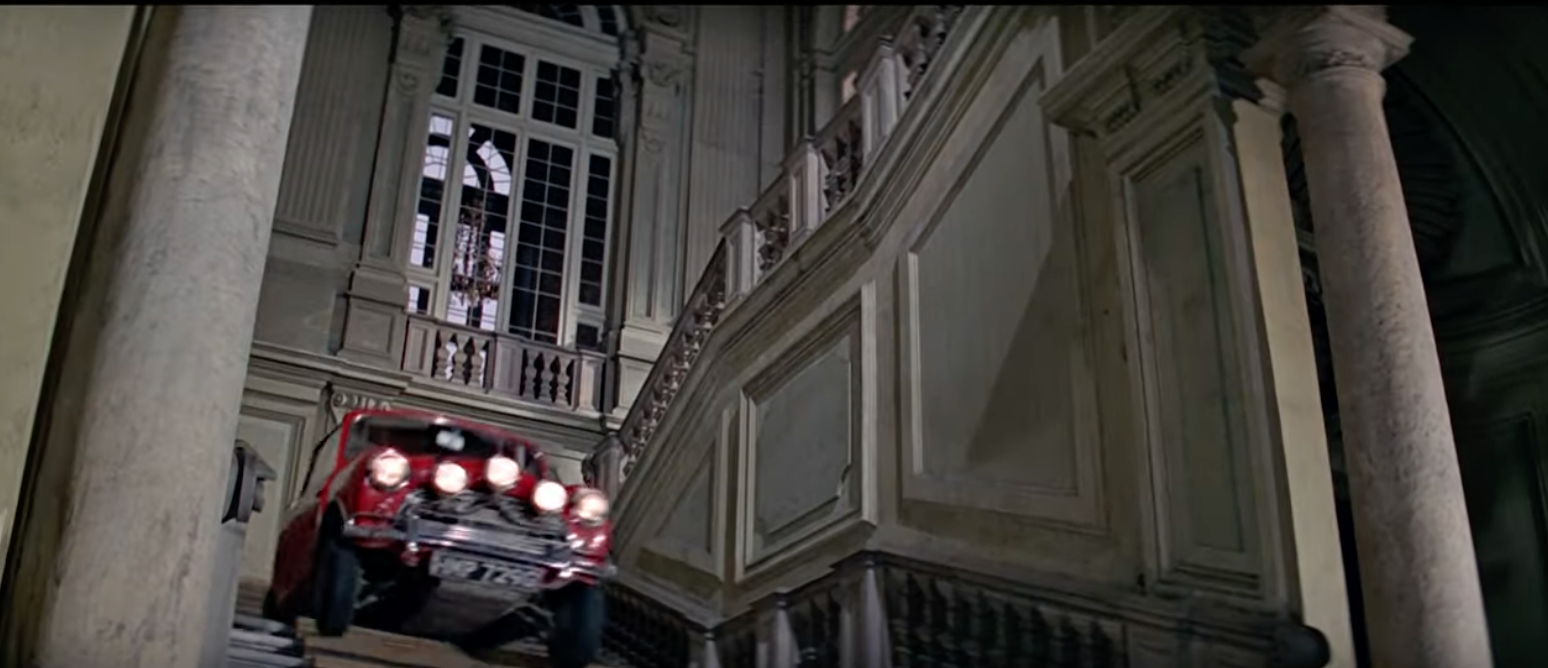

When his Italian partner in crime meets a surreal end on a mountain road courtesy of the Mafia, Charlie Coker (Michael Caine) enlists the help of Bridger (Noel Coward), a mastermind who doesn’t let a long-term prison sentence stop him from running a criminal empire, by appealing to his patriotism. Coker and a diverse variety of colorful associates plan and carry out a daring raid on a secure convoy carrying $4 million in gold, under cover of a traffic jam and an England v Italy football game. After a delightful set-piece involving red, white and blue Mini Coopers racing through, above and below the streets of Turin, the criminals seem to have gotten away with it—but have they?

Criminals from all walks of British life, in a planning meeting

Criminals from all walks of British life, in a planning meeting

The movie is technically SF, in that it contains a scene showing the way in which a computer might be compromised using a piece of malicious software on a magnetic tape—which, when introduced into the Turin traffic system, interferes with the cameras and allows our protagonists to conduct their raid. Happily this seems to be only a theoretical possibility at this point, but it’s an intriguing idea. The movie also draws liberally on the surreal comedy of recent television series like The Prisoner and The Avengers, which are often considered at least nominally science fiction.

The movie’s strengths lie in its pace, its spectacular driving set-pieces and its humour, which manages to be simultaneously proud and self-deprecating. Coker’s motley crew are variously dim-witted, incompetent, oversexed and lacking in foresight, and yet they manage to pull off a daring raid against the clearly much more organised Italian Mafia. The movie also makes satirical comments on the connections between crime and the Establishment in both Britain and Italy, and there’s a suggestion of Tati’s playful anti-technology message in the way in which the traffic system is brought to a standstill and joyous chaos erupts in its wake.

The Minis! They're amazing! They go everywhere!

The Minis! They're amazing! They go everywhere!

It's a little sad, though, that all this joy and unity comes at the expense of disliking our neighbours. Given that the current political situation suggests we need to join the Common Market, the jocular but nonetheless pointed sense of Britain isolated, fighting against Europe and, indeed, the world, could strike a worrying note. I also observe that Coker’s crew contains no one from the Celtic Fringe of this country (relatedly, women also seem to be excluded from the merry band, except as sex objects). However, to be fair, Coker’s raid is initially planned as a joint Italian-British enterprise, the money is coming in to Fiat from China, and there’s a long speech about the relevance of the Italian immigrant community in Britain. So perhaps I’m reading too much into it.

I suspect joining Europe is an inevitability for the United Kingdom. If so, it’s good that we’re coming in with a clear sense of common identity and national pride, showing everyone that we can laugh at ourselves and drive our tiny cars alongside the best of them.

Four stars.

![[September 20, 1969] Cinemascope: Stitched from the past; schemed from the future (<i>Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed</i> and <i>The Italian Job</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690920posters-521x372.jpg)

![[August 14, 1968] The World, the Flesh and Charles Gray (the horror movies <i>Torture Garden</i> and <i>The Devil Rides Out</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/680814posters-1-672x372.jpg)

![[July 24, 1968] Peter Cushing and the Women (<em>Frankenstein Created Woman</em> and <em>The Blood Beast Terror</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/680724posters-601x372.jpg)

![[July 6, 1965] Same Difference (<i>Dr. Who And The Daleks</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/650706daleks-672x372.jpg)