by Kaye Dee

Mr. Barry McGuire should have waited another month to record his hit song Eve of Destruction. Why? Because then his telling line “You may leave Earth for four days in space, but when you return it’s the same old place” could have been made an even punchier by updating it with the latest space flight record of eight days, set by the crew of Gemini 5.

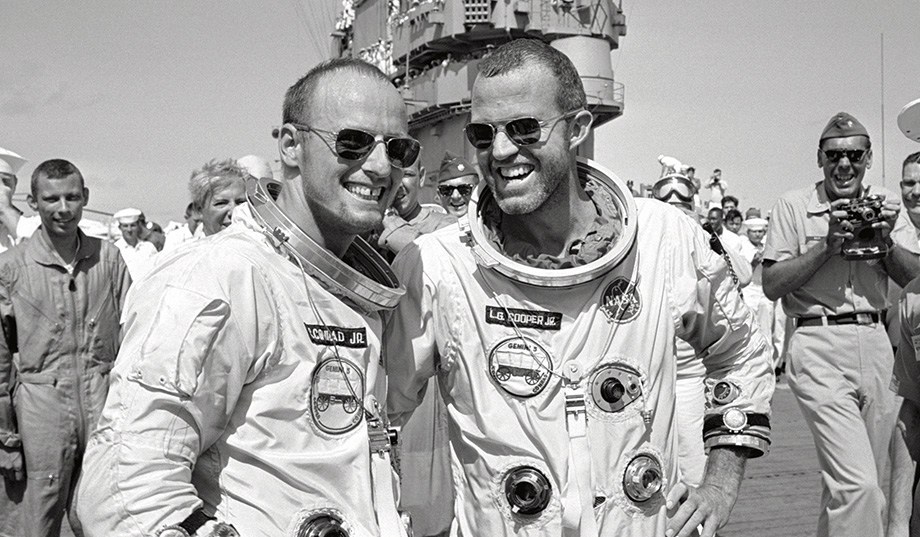

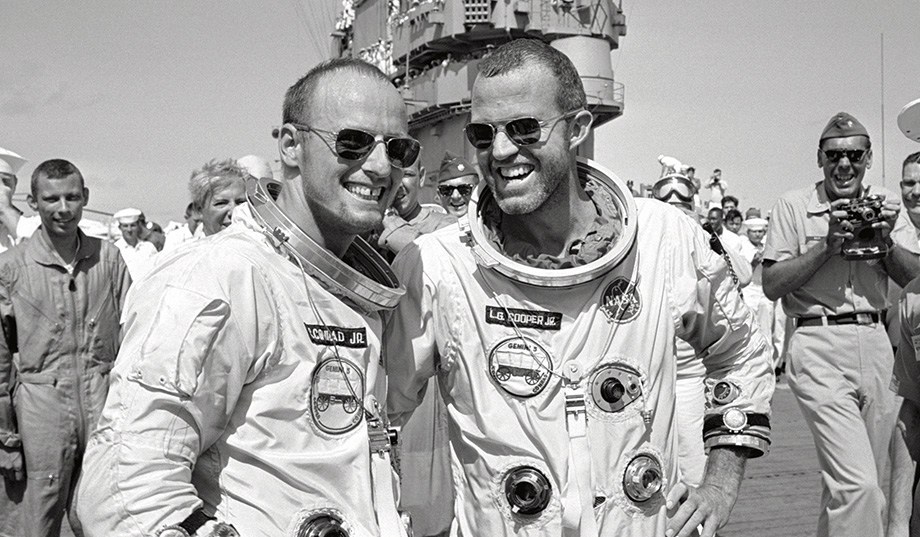

The Gemini 5 crew, Charles "Pete" Conrad (left) and mission commander Gordon "Gordo" Cooper (right), ready to set a new space endurance record

One for the Record Books

The safe return of the Gemini 5 crew yesterday, at the end of a mission dogged by technical problems, not only captured the record for the longest spaceflight to date, it has catapulted the United States into the lead ahead of the Soviet Union for the first time in the Space Race! From the outset, NASA planned for this mission to last eight days, to demonstrate that astronauts could live and work in space for the duration of an Apollo mission to the Moon and back. That this flight time beat the Soviet record of just under five days set by cosmonaut Valery Bykovsky in Vostok 5 in 1963, is a welcome added bonus. Other objectives of the mission included: demonstrating the guidance and control systems; evaluating the new fuel cell system and rendezvous radar; and testing the ability of the astronauts to manoeuvre close to another object.

A Mission Patch: the Start of a New Tradition?

For this crucial mission, NASA paired veteran Mercury astronaut Gordon Cooper, who flew America’s last and longest Mercury mission, with rookie Charles “Pete” Conrad, a member of the second group of astronauts selected in 1962. Because astronauts have been prohibited from naming their spacecraft (following NASA’s displeasure with the name Gus Grissom selected for Gemini 3), Cooper wanted to wear a mission insignia that would symbolise the purpose of their flight. He and Conrad designed a “mission patch”, along the lines of those worn by military units, showing a Conestoga wagon, the type of vehicle used by many of the pioneering families heading into the American West.

The Gemini 5 mission patch as Cooper and Conrad originally designed it, with its pioneer inspired motto (left), alongside the NASA-modified flight version on the right.

On their original design, the wagon carried a motto that was also derived from pioneering times: “8 Days or Bust”. But according to a rumour I’ve heard from my former WRE colleagues, NASA felt that this might leave the agency open to ridicule if the mission didn’t last that long. Because of this, the embroidered patches that Cooper and Conrad wore on their spacesuits during the flight had the ambitious slogan covered by a piece of cloth. But I like the idea of each mission having its own symbolic insignia, so I hope that mission patches become a tradition for future spaceflights.

Launching into History

Gemini 5 was originally supposed to launch on 19 August, but problems with the telemetry programmer and deteriorating weather delayed the lift-off until 21 August. Like previous Gemini missions, Cooper and Conrad lifted off from Launch Complex 39 at the Cape Kennedy Air Force Station. I understand that NASA will continue to use it for the rest of the Gemini programme while its new John F. Kennedy Space Centre is being constructed nearby for the Apollo missions.

During the launch, the astronauts experienced a type of vibration known as “pogo” (as in pogo stick!) which seems to have momentarily impaired their speech and vision. This will need to be further investigated to determine if it poses a threat to crew health and safety on future flights. After the launch, part of the Titan II launch vehicle's first stage was found floating on the surface of the Atlantic Ocean and retrieved; I expect it will go on display in a museum after it has been thoroughly studied.

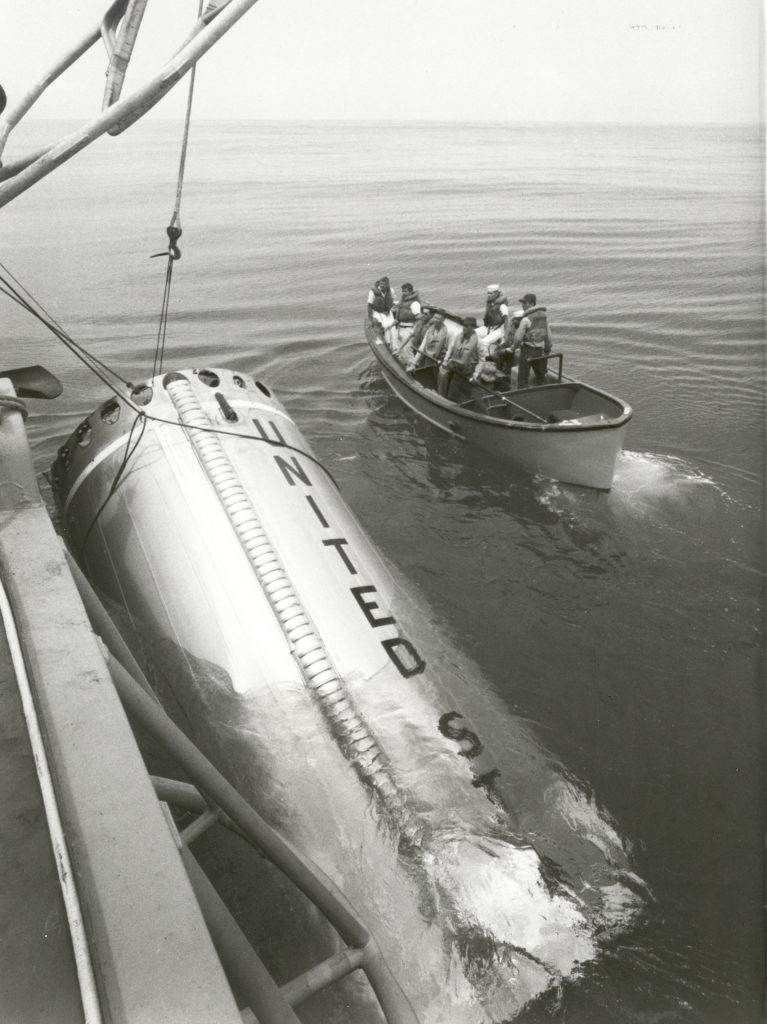

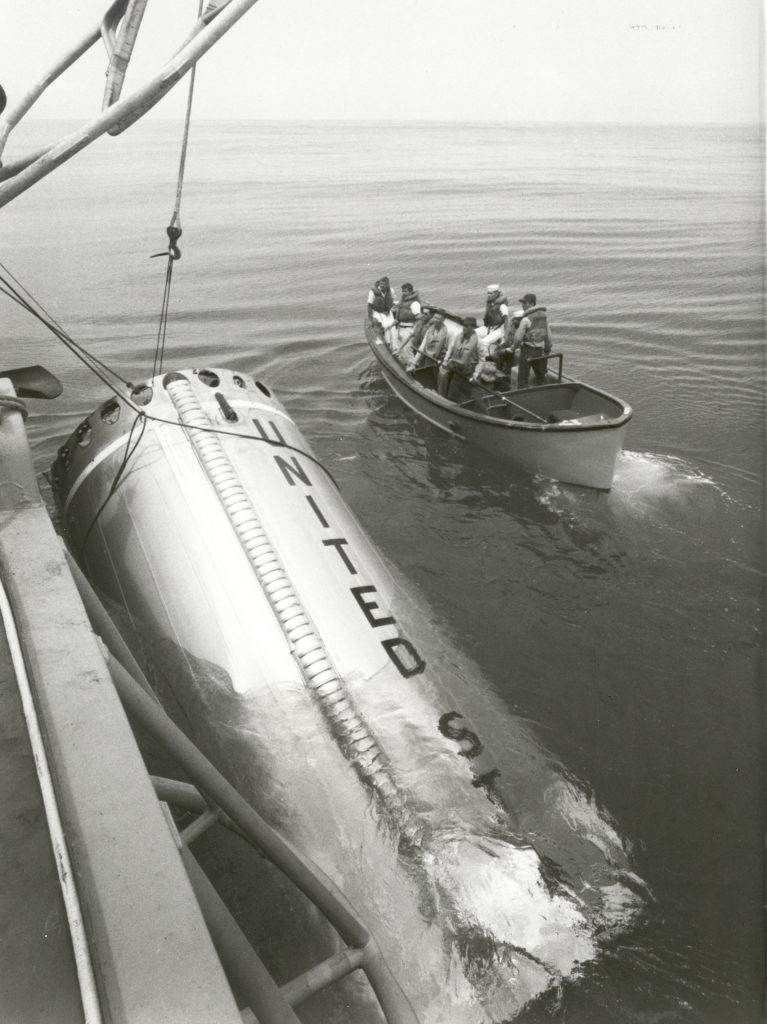

Recovering the upper half of the Titan II launch vehicle first stage from the Atlantic Ocean

Dr. Rendezvous to the Rescue!

Just over 2 hours after launch, the Rendezvous Evaluation Pod (REP, nicknamed Little Rascal, I’m told) was ejected into orbit from Gemini 5. The crew were supposed to practice rendezvous techniques with this mini satellite. However, about 4 hours into the flight, very low oxygen pressure in one of the spacecraft’s fuel cells that provide onboard power led to a decision to shut both fuel cells down. Gemini 5 is the first mission to use this new method of generating onboard power, but without the fuel cells, the spacecraft has only a limited battery power reserve. As a result, Gemini 5 was powered down, drifting along in "chimp mode," without active control by the crew. It looked for a while as if the mission might be “2 days and bust”, but ground tests showed that the faulty fuel cell should work even with low oxygen pressure and both fuel cells were gradually put back into operation, enabling the mission to continue.

An artist's impression of the Gemini 5 Rendezvous Evaluation Pod, as the mission should have unfolded. Unfortunately, the battery on its flashing beacon, which helped the astronauts to see it against the blackness of space, died before the fuel cell issues were resolved.

The fuel cell failure meant that the REP experiment, and others, had to be scrapped. However, astronaut Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin devised a rendezvous simulation to test the Gemini 5 crew, which would require them to rendezvous with a specific point in space. The other astronauts don’t call Aldrin “Dr. Rendezvous” for nothing: he has a doctorate in Astronautics, specialising in orbital mechanics, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology! The “phantom rendezvous” test took place on the third day of the mission. Cooper and Conrad proved that precision manoeuvres could be successfully accomplished, carrying out four different rendezvous manoeuvres using the Gemini’s Orbit Attitude and Manoeuvring System (OAMS).

On August 24 Cooper reached a cumulative total of 98 hours in space, over his two flights, taking the record for the longest time spent in space by an American astronaut. By the end of the mission he was the world record holder for time spent in space, leaving Bykovsky’s endurance record well behind!

Fuel Cells for Survival

A diagram showing the fuel cells installed on Gemini 5. Despite their problems on this mission, NASA expects to use fuel cells to provide electrical power and water on future space flights.

Another fuel cell problem surfaced on day four of the mission, but this was relatively minor, which was fortunate as the fuel cells not only produce electrical power for the Gemini spacecraft, but also provide the water supply for the crew. Like a battery, a fuel cell uses a chemical reaction to create an electric current. The Gemini fuel cell uses liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen to generate electricity, which creates water as a by-product. Cooper and Conrad reported that the water had a lot of gas bubbles in it (with a predictable intestinal result!) and that it also had a taste they didn’t like. However, it was drinkable when mixed with Tang powdered orange drink, so I think that this will become a staple on future missions (a good advertising opportunity there!).

A plentiful supply of water also means that NASA will be able to provide the astronauts with more rehydratable foods from now on, although the Gemini 5 crew apparently did not have much of an appetite during the mission, only consuming about 1000 calories a day, instead of the planned 2700 calories.

Thanks to fuel cell-produced water, future NASA missions will have more rehydratable foods available. This sample Gemini meal includes a beef sandwich, strawberry cereal cubes, peaches, and beef and gravy. Astronauts use the water gun to reconstitute the food and scissors to open the packages

More Problems to Endure

The fifth day of the mission saw a major problem develop when one set of OAMS thrusters began to malfunction. This meant that all experiments where the thrusters needed to be used were cancelled. One cancellation was a great disappointment for us here in Australia. The Visual Acuity Test was designed to gauge the acuity of an astronaut’s vision from space, by observing patterns laid out on the ground.

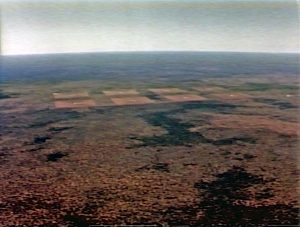

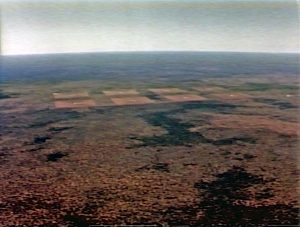

Two test sites were prepared for this Gemini 5 experiment: one at Laredo, Texas and the other on Woodleigh sheep station (ranch), located about 90 miles south of Carnarvon, Western Australia. Carnarvon is the site of NASA’s largest tracking station outside the United States, combining both a Manned Space Flight Network facility and a Space Tracking and Data Acquisition Network station. At Woodleigh, piles of white sea-shells were bulldozed into carefully chosen patterns to determine the smallest pattern the astronauts could discern through the window of their spacecraft.

The Visual Acuity Test patterns at Woodleigh station seen from the air. Though they were composed of very white shells from a nearby beach, I think they might have been difficult to spot from space even under ideal conditions.

However, when this experiment should have been performed on 26 August, Gemini 5 was again drifting along powered down, due to the fuel cell and OAMS problems and could not maintain a stable view of the ground. The astronauts could see the smoke markers identifying the Woodleigh site but not the experimental patterns themselves due to the spacecraft's attitude. Attempts to view the site on later orbits were, unfortunately, no more successful, although the crew could see the lights of Carnarvon and Perth on night-time orbits.

During this powered-down period, Cooper and Conrad became quite cold and experienced feelings of disorientation caused by stars drifting past the windows as their capsule slowly rotated. Eventually, Cooper put covers on the windows to shut out the sight. Not only did they have difficulty sleeping, the crew also had to contend with persistent dandruff, apparently due to the low cabin humidity. The dry, flaky skin they shed settled everywhere, making for an unpleasant cabin environment. Even the instrument panels became partially obscured by dandruff!

No wonder the Gemini 5 crew found it difficult to sleep, when they were crowded together in a space about the same size as the front seat of a VW Beetle! Sleeping in alternate shifts was was not successful, but even sleeping at the same time did not make for a restful "night".

Although the mission’s technical problems caused some experiments to be cancelled, many others were still successfully carried out, including medical and photographic experiments. Among the crew's space science pictures were the first photographs of the zodiacal light and the gegenschein taken from orbit. Photographs of the Earth taken from space are also expected to produce detailed images that will have scientific, military and intelligence value once the films taken in flight are processed. I'm really looking forward to seeing them.

100 Orbits

On 28 August, Gemini 5 became the first manned spacecraft to complete 100 orbits of the Earth. In recognition of the achievement, Mission Control in Houston relayed 15 minutes of Dixieland music to the two astronauts, making Capcom Jim McDivitt the first space disc jockey! Because of the cancellation of experiments during the mission, Conrad had previously said he wished he had brought a book to read, or some music to listen to, and both Cooper and Conrad had expressed a preference for Dixieland music. Later that day, the Capcom at Houston also read up to the crew a little poem that Conrad’s wife, Jane, had written.

From Space to Shining Sea

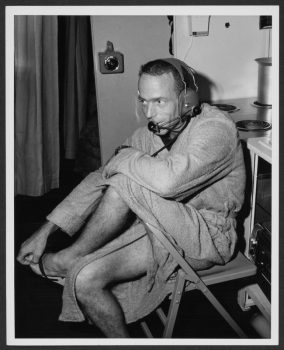

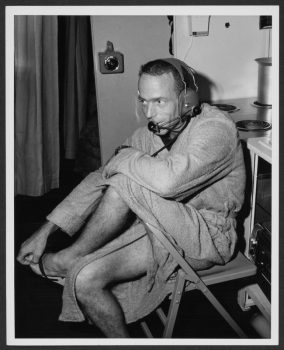

A few hours before Gemini 5 returned to Earth yesterday, Gordon Cooper made a very special long-distance call – to fellow Mercury astronaut Scott Carpenter, who is living and working aboard the US Navy’s Sealab II facility, 205 feet beneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean near La Jolla, California. This radio call was apparently made to test the effectiveness of an undersea electronics lab installed on Sealab II, but it was also a nice piece of publicity for NASA and the Navy.

Mercury astronaut turned aquanaut Scott Carpenter, inside Sealab II, talks to Gordon Cooper aboard Gemini 5. Don't ask me how I got this photo!

Eight Days Without Busting!

Finally, on 29 August, at 190 hours, 27 minutes, and 43 seconds into the mission, retrofire commenced and Gemini 5 was on its way home. To demonstrate the level of control provided by the Gemini spacecraft design, the astronauts controlled their re-entry, rotating the capsule to create drag and lift. Unfortunately, due to an error by a computer programmer, Gemini 5 splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean 80 miles short of its target landing site, but the crew were quickly located and retrieved. Gemini 5 ended just a few hours short of the planned eight days, but the epic mission had come to a successful conclusion and lived up to its motto – it was most definitely not a bust!

Safely home! The crew of Gemini 5 look tired, but elated, after what what Conrad has described as "“eight days in a garbage can”. Notice those "censored" mission patches, whose motto was right after all!

![[November 26, 1969] From the Earth to the Moon…and back (Apollo 12)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691126crew-672x372.jpg)

![[September 18, 1966] Soaring Higher (Gemini 11)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Gemini-11patch-2-308x372.jpg)

![[August 30, 1965] 8 Days or Bust! (Gemini 5's epic space mission)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Cooper-and-Conrad-672x372.jpg)