by Gideon Marcus

Goodnight, Percy

If you're anything like me, Peyton Place is something that happened to other people. After all, last season, the first primetime soap opera was scheduled opposite Laugh In, and before that, the 9:30 PM slot in the midst of ABC's insipid Tuesday-night line-up.

But now I feel a little bad that the groundbreaking show is being taken off the air. Based on the 1956 book of the same name by Grace Metalious, the Massachusetts-set serial was salacious for the time, involving as it did a lot of S-E-X, divorce, blackmail, murder, and more. Jack Paar called it "Television's first situation orgy." Johnny Carson quipped that it was "the first TV series delivered in a plain wrapper."

Stars Diana Hyland (standing), Pat Morrow (in can), and Tippy Walker

At one point a few years ago, some 60 million folks tuned in each week for the fun. But nowadays, when the local theater is going blue/stag, and Candy is a mainstream hit ("Is Candy faithful? Only to the book!"), Peyton Place all seems a bit staid. They tried to mix things up by bringing in more teen storylines and also integrating the cast by hiring Percy Rodrigues (Star Trek's Commodore Stone) as the local doctor.

with Ryan O'Neal

Still, you can't beat Dick and Dan, and the series plummetted in the ratings (really—what were they thinking, scheduling it across from Rowan and Martin?) After 514 episodes, the show is going off the air. Which, of course, just means we'll see it endlessly in morning reruns opposite the regular soaps—and you can bet we'll get a revival sometime in the future. In the meantime…

"Goodnight, Lucy. Goodnight, Marshall Dillon. And goodnight to all you kooks on Peyton Place."

Goodnight, Johnny

by Kelly Freas

ABC at least knew when to pull the plug on its sinking stone. Analog editor John Campbell, while he did some brilliant work in the '30s and '40s, seems content to stuff his magazine with the dullest dreck that science fiction has to offer. The latest issue is Exhibit 1 for the prosecution:

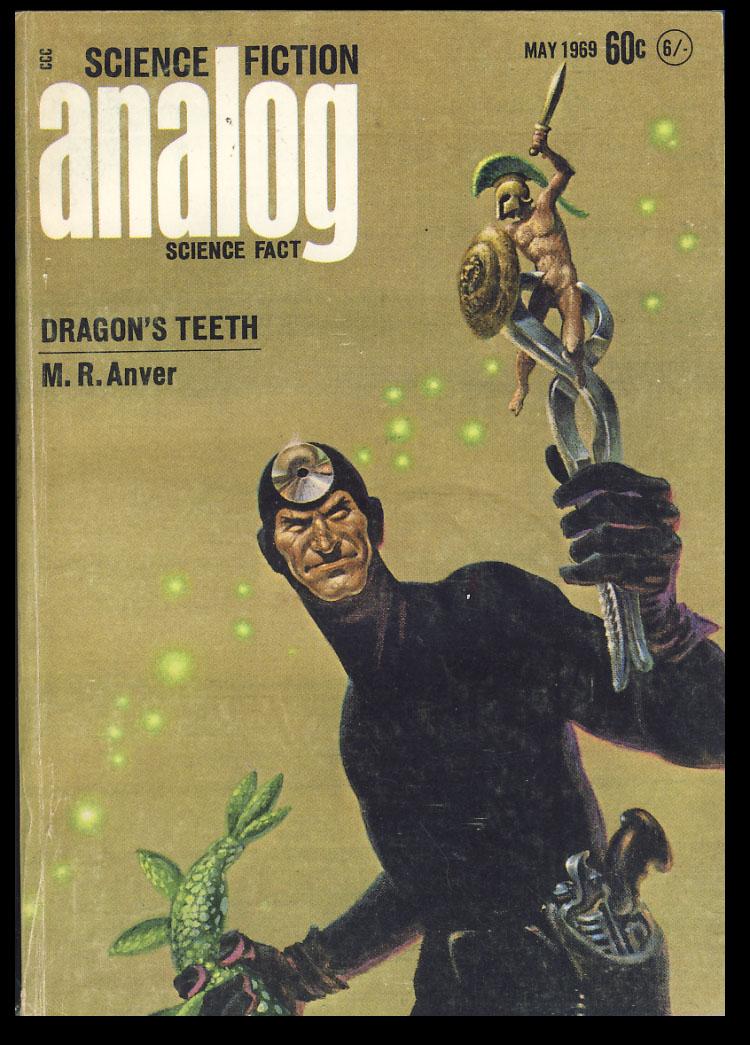

Dragon's Teeth, by M. R. Anver

by Kelly Freas

A peace conference on a neutral asteroid promises to end a brutal war between humanity and the alien Cadosians. But a faction of extraterrestrials has plans to distrupt the summit by introducing a deadly virus. The question is how they'll smuggle it in…or in whom?

This is a competently put together adventure/mystery—no more, and no less. As such, it's a fine first effort from Mr. Anver, but nothing to write home about.

Three stars.

The Chemistry of a Coral Reef, by Theodore L. Thomas

Science writer and fictioneer Ted Thomas offers up a long piece on coral reefs and how they're made. For an article on stuff that takes place in our oceans, it's awfully dry. Well, at least I know now what they're made of: calcium carbonate. Good for all those fish with indigestion, I guess.

Two stars.

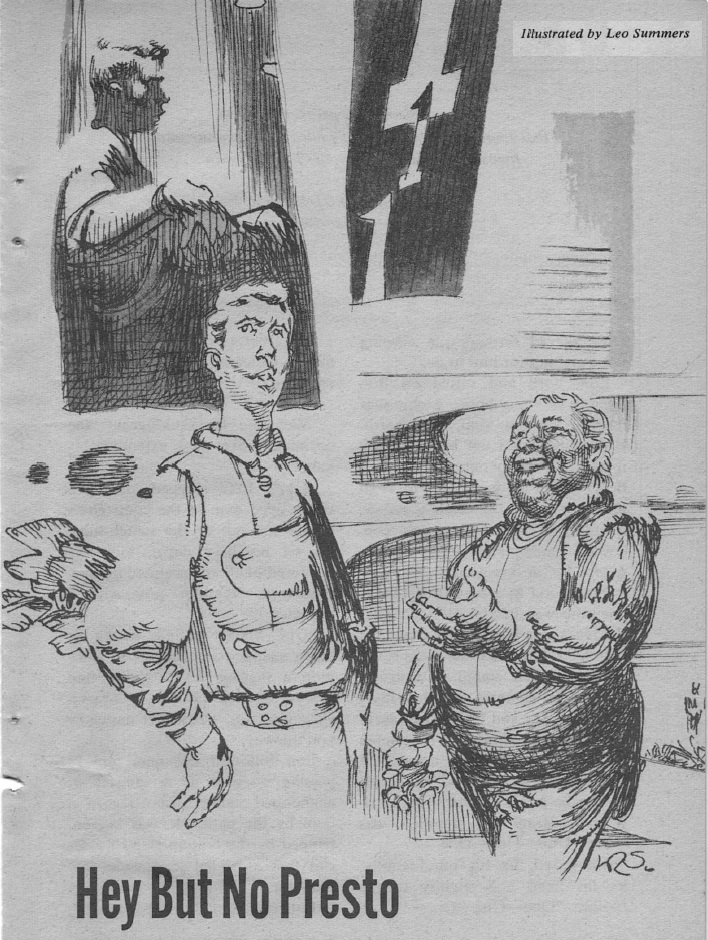

Operation M. I., by R. Hamblen

by Leo Summers

Three weeks of hyperspace are crushingly dull, and the intergalactic service is worried about the morale of their solo couriers, who have to endure the period without diversion. Apparently, books and booze aren't enough.

So the ship's computer on the latest FTL ship is programmed to act like a nagging mother-in-law so each pilot is more irritated than bored.

Terrible piece. One star.

Persistence, by Joseph P. Martino

by Kelly Freas

This is a sequel to the story Secret Weapon. The Terrans have now got a leg up on their war with the Arcani, now destroying 3-4x as many vessels as they are losing. However, this proportion is still below what the Big Brains in military intelligence expected. Our hero, Commander William Marshall, is certain that the aliens have developed Faster Than Light ("C+") communications and are using them to thwart our patrols.

The story is devoted to the reverse engineering of a captured Arcani corvette, tediously going through each electronic gizmo to see how it is wired and what it is wired to. Eventually, the existence (or lack) of a C+ radio will be proven.

Once again, the story is dull as dirt, and worse, poorly edited. There's an art to writing successive paragraphs using different words. Martino will repeat set phrases several times in a row, the sign of an unfiltered brain-to-typewriter stream of consciousness.

Also, women of the future still remain in the 1950's, socially.

Two stars.

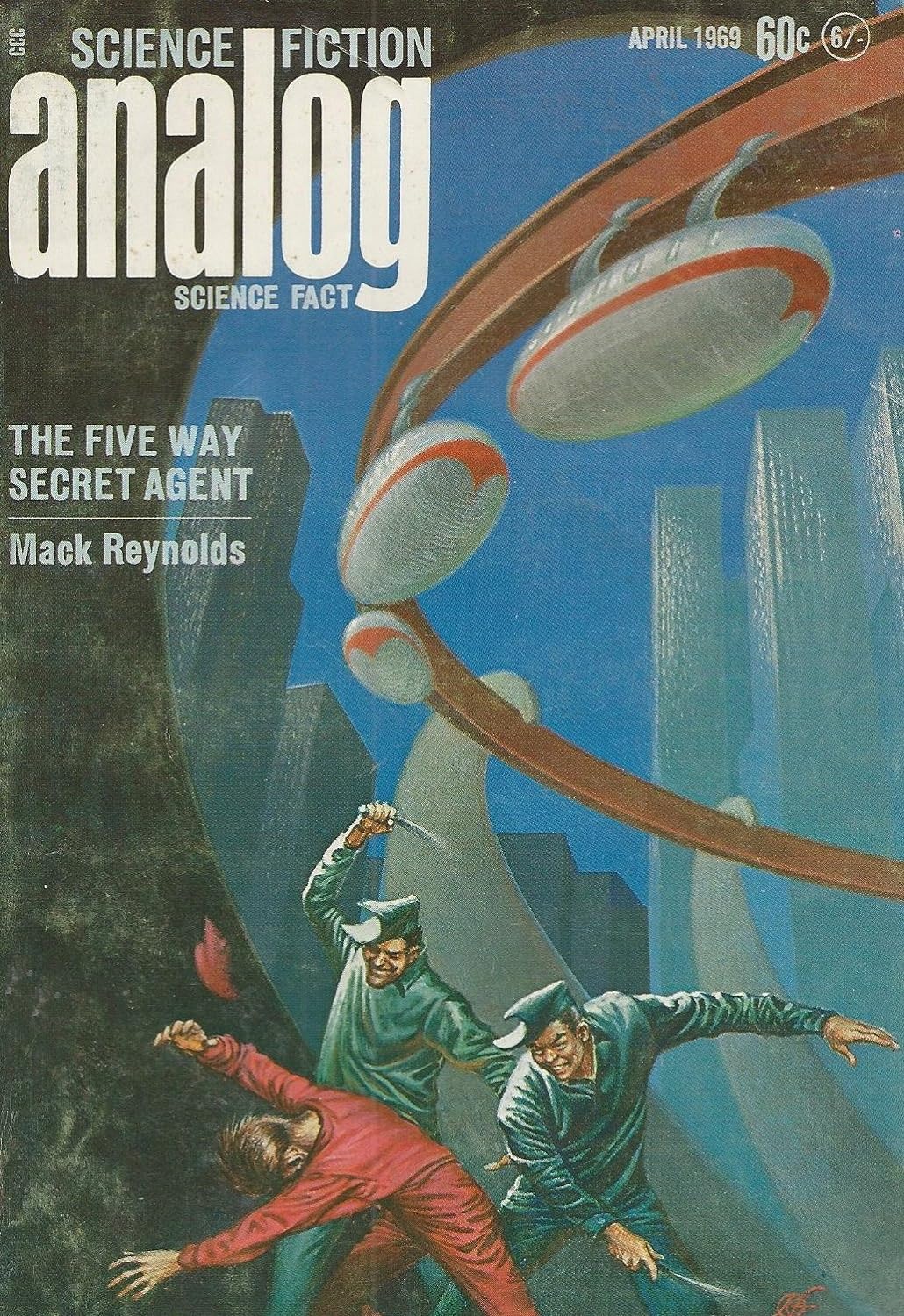

The Five Way Secret Agent (Part 2 of 2), by Mack Reynolds

by Kelly Freas

As we saw last month, Rex Bader, last of the private dicks in the People's Capitalism of America's late 20th Century, had been tapped by no fewer than five organizations to spy on each other as Bader went off to Eastern Europe and make contacts. This passage explains it all:

He stared at the screen in disbelief.

This whole thing was developing into a farce. Roget wanted him to make an ultra-hush-hush trip into the Soviet Complex to contact his equal numbers with the eventual aim of creating a world government based on the international corporations.

Sophia Anastasis, of International Diversified industries, thought such a world government would upset the status quo to the detriment of what was once called the Mafia, and wanted all details.

John Coolidge and his group [the successor to the FBI] were afraid such changes would upset the governmental bureaucracy and the military machine and wanted to prevent it from happening.

Colonel Simonov felt the same from the Soviet viewpoint, and wanted to maintain the status quo.

Dave Zimmerman was all in favor of world government but wanted the Meritocracy which would run it to be elected from the bottom up in each corporation, rather than being appointed.

And every damned one of them thought that their part of the operation was a secret.

Once Bader gets to Czechslovakia and Romania, the book reads like typical Reynolds: historical parallels (none after 1969, of course), tourism (we learn about the national drinks of the Warsaw Pact), and mildly droll high jinks. It seems that Bader's cover is blown wherever he goes, suggesting a traitor somewhere in the works among his five employers.

There could have been a good mystery here, but it's all thrown in too little, too late. Moreover, it's clear that this two-part serial is really just the first half of a longer book.

As a result, the whole is lesser than the sum of its parts. I give this segment three stars, and three stars for the book as a whole (so far).

Initial Contact, by Perry A. Chapdelaine

by Kelly Freas

The Eridanians are coming! Responding from signals broadcast by Project Ozma, an alien ship has been dispatched from Epsilon Eridani. After twelve years at near light speed, the vessel is about to arrive—and the press is filled with concerns of an impending alien takeover.

It all stems from a mistranslation of their latest message, suggesting their intent is conquest rather than coexistence. In the meantime, there is a lot of Keystone Copping as the head of the Ozma IX project tries to tamp down on the paranoia.

by Kelly Freas

The best part of the story is the "universal message" broadcast by the Eridanians, hatched up by author Chapdelaine. He explains it in the story—see if you can figure it out yourself.

But in the end, the story is rather pointless and forgettable. Two stars.

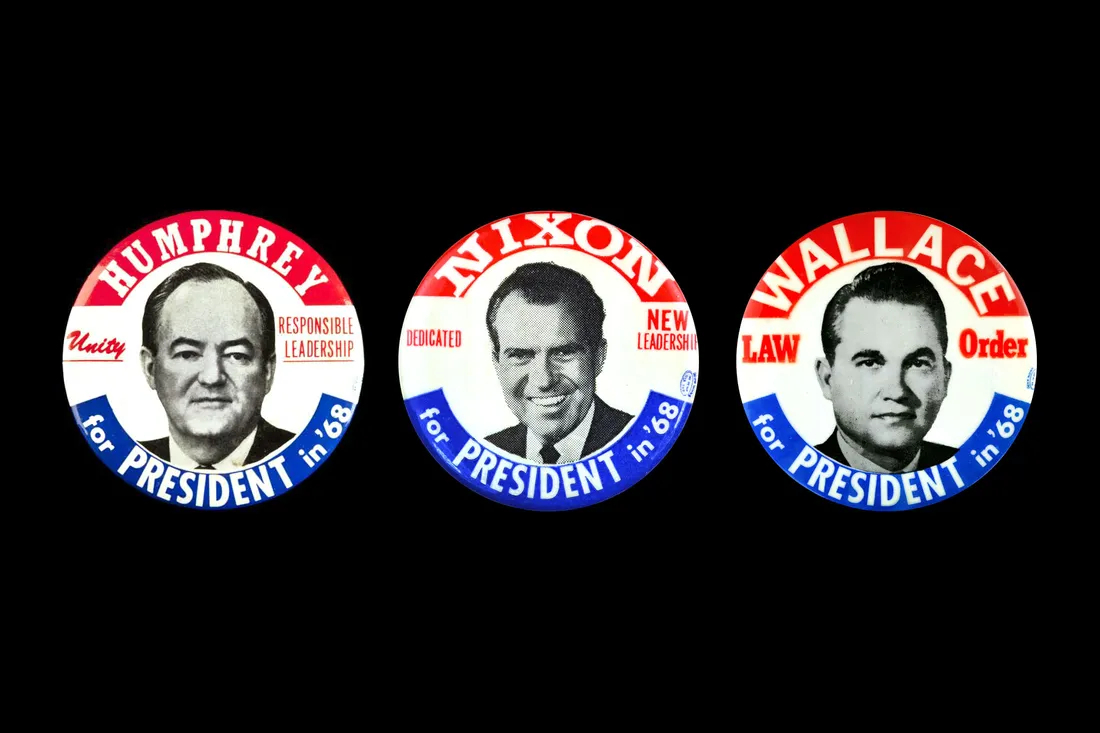

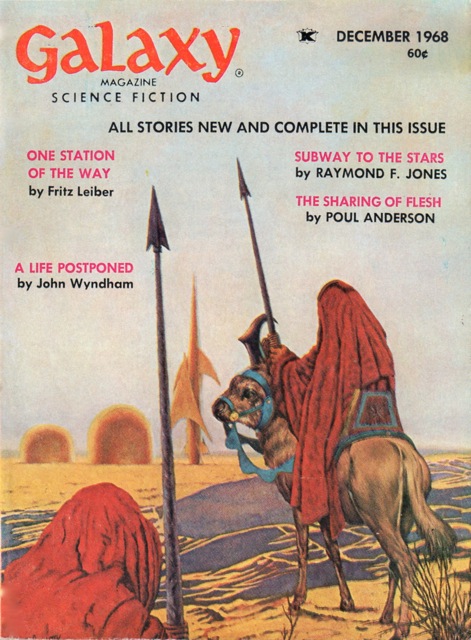

Goodnight May

Doing the math, I find that April (postmarked May on the magazines) was a dreadful month for short science fiction. Not a single magazine topped 3 stars, and Analog came in at a dismal 2.3. For posterity, the rest were New Worlds (2.7), Venture (2.7), Amazing (2), Galaxy (3), and IF (3), and Fantasy and Science Fiction (2.7)

Even more disheartening: you could take all the 4-star works (nothing hit 5 stars this month) and barely fill a Galaxy-sized thick digest. Women wrote 20% of all the new pieces published in April, which sounds impressive until you realize that six of the works were short poems in New Worlds, all by Libby Houston.

I am already hearing rumblings about Galaxy and IF's editor Fred Pohl getting the heave-ho, and Amazing's editorial musical chairs is legendary. ABC dumped Peyton Place—is it time for someone to cancel John Campbell?

![[April 30, 1969] Eulogies (May 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690430analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 4, 1969] Hey, Mack! (April 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/690331cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 28, 1969] Slidin' (February 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690128cover-672x372.jpg)

A Womanly Talent, by Anne McCaffrey

A Womanly Talent, by Anne McCaffrey

![[November 6, 1968] Who's the one? (December 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681106cover-471x372.jpg)

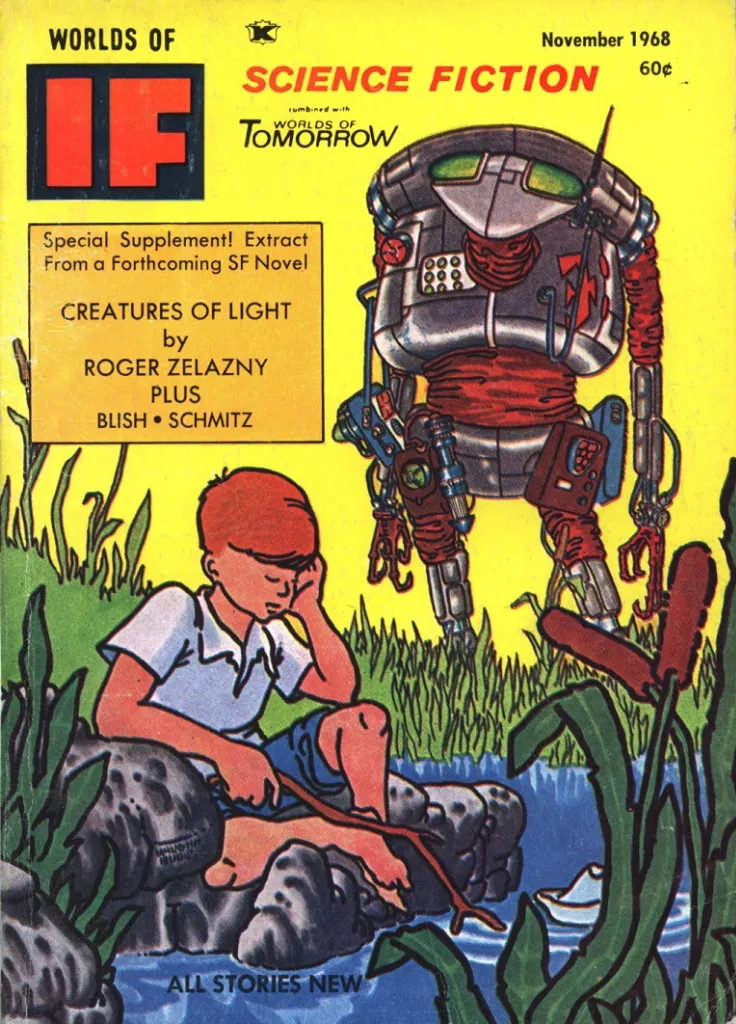

![[October 2, 1968] Future History Lessons (November 1968 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/IF-1968-11-Cover-672x372.jpg)

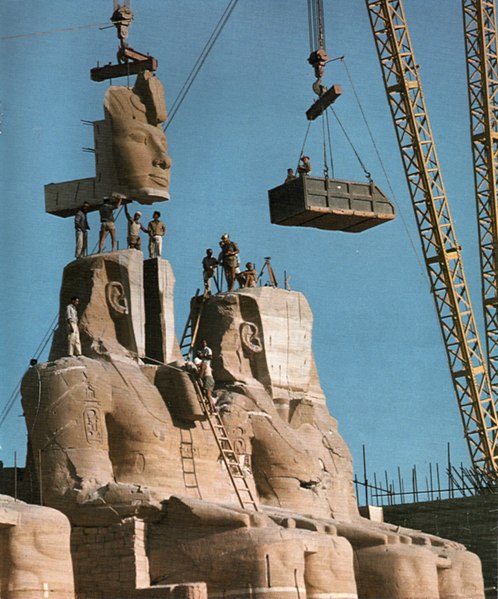

Ramses gets a face lift.

Ramses gets a face lift. The Waw is bored. Art by Vaughn Bodé

The Waw is bored. Art by Vaughn Bodé![[July 10, 1968] Back in the Saddle Again (August 1968 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/680710cover-672x372.jpg)

![[November 29, 1964] All-star (December 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/641129cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 30, 1964] The Deadly Barrier (November 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641030cover-672x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1964] Terrestrial Adventures (October 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/641002cover-672x372.jpg)