by Gideon Marcus

LosCon in Los Angeles!

It's been an exciting November for the Journey. After a sad interlude on the East Coast, which saw the untimely death of our President, we flew back to Los Angeles for a small science fiction convention put on by the Los Angeles Science Fiction Society. It was great fun, a real class act. Not only did we get to put on a show (in which the assassination, of course, featured prominently), but we also met Laura Freas, wife of Kelly Freas, the illustrator who painted Dr. Martha Dane. As y'all know, Dr. Dane graced our masthead until very recently, and she remains the Journey's avatar.

And for those of you who missed the performance, we got it on video-tape.

At last, success for NASA

I read an article in Aviation Weekly that noted that 1963 just hasn't been a great year for NASA space shots. There have only been eight successful missions thus far. Unlike in the old days (you know, five years ago), when satellites didn't fly because of balky rockets, now missions are more likely to be delayed for lack of funding on the ground or for thorny technical issues as mechanisms get more complicated.

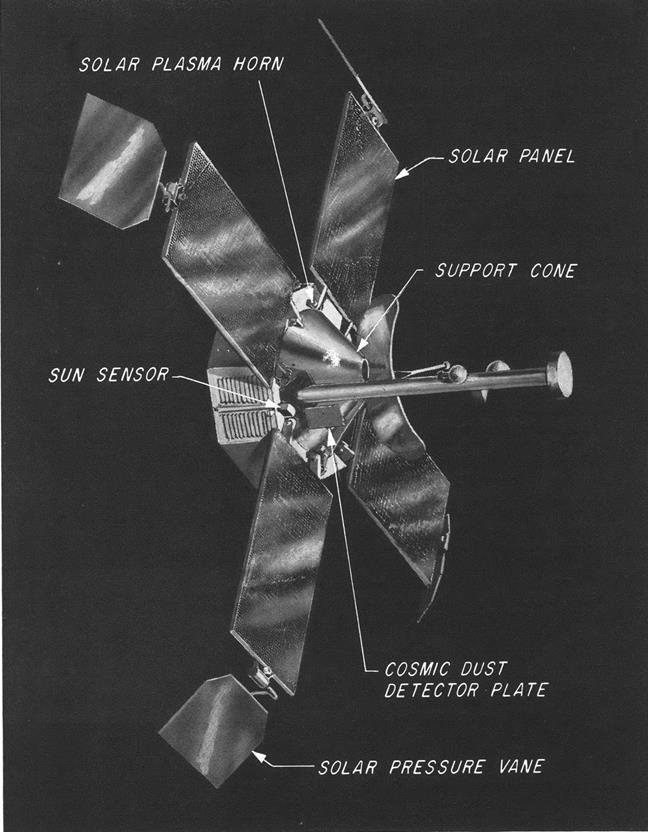

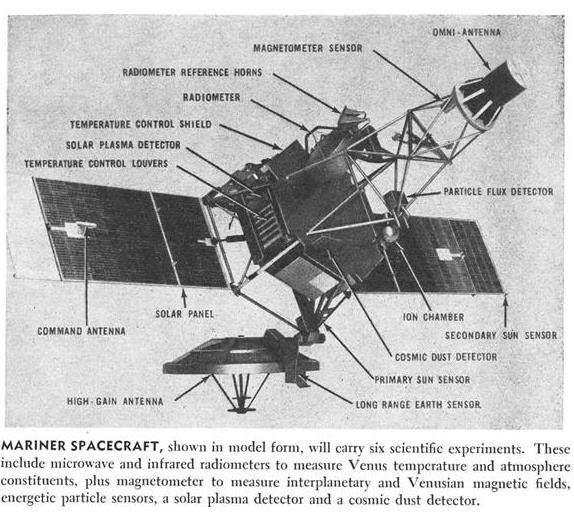

But successes do happen, and on November 27, Explorer 18 soared into orbit. Also known as the Interplanetary Monitoring Platform (IMP), it is essentially a deep space explorer. At the closest point in its orbit, it zooms at an atmosphere-scraping 160 kilometers in altitude, but at its furthest, it flies up to a quarter million kilometers out — more than halfway to the moon.

IMP is the first of seven satellites that will monitor the sun's output over a long period of time, measuring its ups and downs over the course of its 11 year activity cycle. It will also measure interplanetary magnetic fields, the speed and composition of the solar wind, and the strength of the cosmic rays that shower the solar system from intergalactic space.

In many ways, Explorer 18 continues the missions of Explorers 10 and 12, spacecraft that made incredible discoveries about our local space environment. What makes IMP so special is its size and endurance: it will be in space much longer than its predecessors, and its more advanced instruments are capable of more refined measurements.

It is also hoped that IMP will be for interplanetary space what TIROS is for Earth — a weather satellite providing up to date information on the environment "up there." Thus, Explorer 18 will not only expand our knowledge of interplanetary physics, it will also be an early warning system, alerting astronauts as to upcoming solar flares and other potentially dangerous events.

Pretty neat!

Last magazine of the year

Every month, the Journey does its level best to review every science fiction magazine that gets published. As far as I can tell, we cover all the regular American ones plus the British New Worlds (only Science Fantasy, also British, escapes our coverage). By tradition, Analog is the covered last, and thus, the December 1963 Analog is the last magazine of the year. Once this one is reviewed, we can finally get down to the fun business of determining the stats: which mag had the best stories, the most consistent quality, the most women published, and so on. Call it SFnal baseball.

So how was this last issue? Read on!

The Nature of the Electric Field, by John W. Campbell

In addition to a nonsensical editorial, Editor Campbell wastes several oversized pages with the reprint of a century-old treatise on electricity. I guess it's to show how times change, and therefore, we shouldn't be so quick to denounce things like Dianetics, reactionless drives, psionics, dowsing, and other pseudo-sciences.

One star.

Cracking the Code, by Carl A. Larson

Larson's article is on DNA and scientists' attempts to understand how a sequence of amino acids can be the blueprint for all of life's manifestations. It's a subject that would have been better handled by Asimov…or really, anyone else. On the other hand, some of Larson's poetical turns of phrase are cute, like analogizing cells to an alien race whose environment is so utterly foreign to our ken, and that's why it's taken so long to decipher their language.

Two stars, I guess.

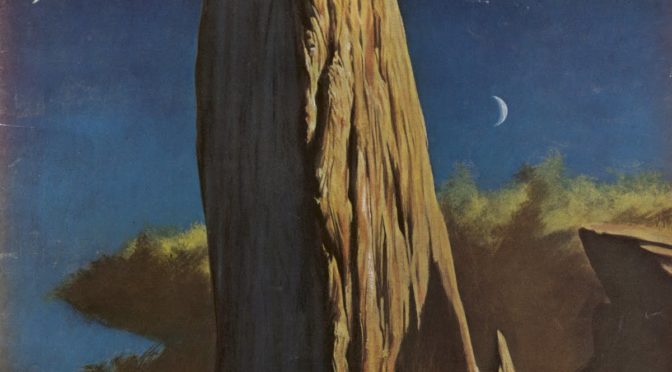

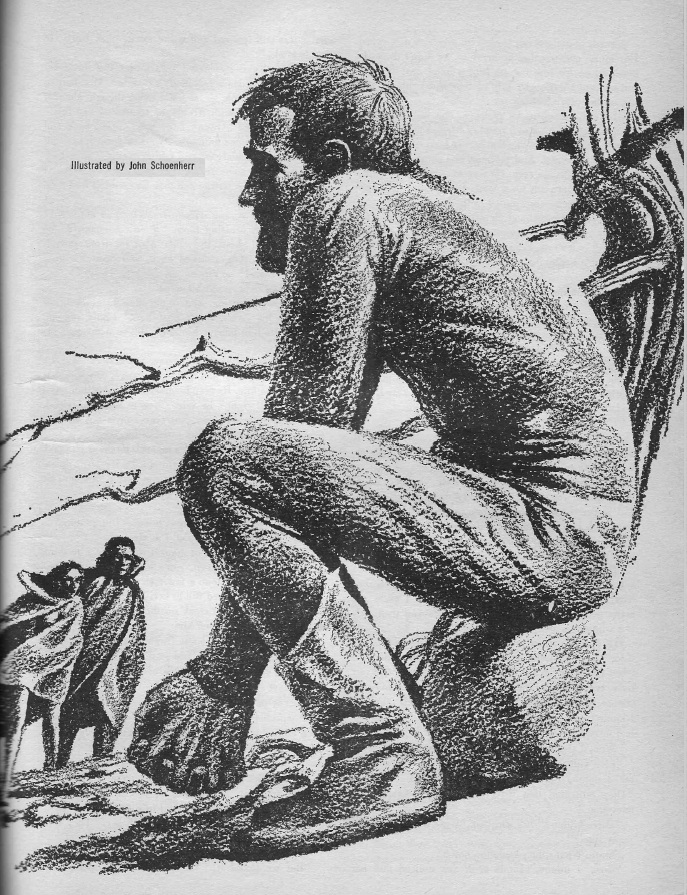

Dune World (Part 1 of 3), by Frank Herbert

I was mistaken when I called this new serial Herbert's first novel. He had a serial back in 1956 called Under Pressure that I must have read some seven years ago, but I couldn't tell you what it was about if you put a gun to my head.

Anyway, this new one seems to be generating a lot of buzz, and I can see why. It features Paul, 15 year-old scion to House of Atreides, whose father, the Duke of Atreides, has been granted the fiefdom of Arrakis. Arrakis — desert planet — Dune. This barren wasteland, where water is worth its weight in platinum, offers but one export: Melange, the geriatric spice that affords immortality, cures ailments, and tastes really good, too. As Arrakis is the only source of melange, control of the planet is a sought plum, indeed.

Except, the Duke knows it is a trap set by the planet's former masters, the Barony of Harkonnen. In collusion with the Padishar Emperor, Harkonnen has hatched a complicated plan to humiliate and discredit (and probably kill) the Duke, a scheme which whose intricacy might even give Machiaveli pause.

There is a lot to admire in this new work. It's a fresh universe, highly developed, with a lot of attention to detail and inclusion of many foreign cultural influences. Women play a prominent role, with the genders being apparently somewhat segregated, each having their own spheres of power. There are at least two important female characters, something I'm always delighted to find in my science fiction.

One of the aspects of Herbert's world is the conscious disdain for, and even ban on, the use of computers. Instead, human "mentats" have been bred for the ability of calculation. This not only creates an interesting new class of person, it neatly relieves the author of predicting the development of electronic brains.

Dune Planet is not, however, an unalloyed success. In the hands of Cordwainer Smith or even Mack Reynolds, folks who have a deep grounding in other cultures as well as the writing chops to convey them, it would be a masterpiece. Herbert, on the other hand, is a pretty raw writer. His stuff can be creaky and dull, the viewpoint shifts from paragraph to paragraph, and his use of ellipses dots is…exuberant (they say we hate most in others what we dislike about ourselves; Herbert writes a bit like I did not long ago before certain editors whipped me into shape).

So, three stars so far, but I'm still reading and look forward to more.

Conversation in Arcady, by Poul Anderson

In George Pal's The Time Machine, Rod Taylor arrives at the far future and discovers humanity living under (seemingly) idyllic circumstances. They no longer need toil for food, shelter, or clothing. They do not fight each other nor feel the need to rule. At first impressed, the time traveler is dismayed to find that the desire to advance, the struggle to improve has been lost. In perhaps the most effective scene of the movie (at least, it was for me), Taylor finds shelves of books that crumble to dust at the slightest touch.

Poul Anderson's latest is a note for note copy of this scene with the exceptions that 1) Anderson's Eloi are not so simple and childlike, 2) there are no Morlocks fattening up people for supper, and 3) the time traveler can see nothing positive about the situation whatsoever.

I think Anderson is trying to say something poignant, that our race is nothing without the need to better itself. Or perhaps he's striving for a subtler point — that those who only find meaning in struggle can never find peace, and maybe peace isn't a bad thing. Or maybe he's saying both things at the same time.

I think he was going for just the first, though. Three stars.

The Right Time, by Walter Bupp (John Berryman)

John Berryman's series is set in the current world but where psionics are common (but secret). It's a perfect fit for Analog what with Editor Campbell's peculiar pseudo-scientific beliefs, yet somehow Berryman's stories manage to be good. This one, about a telekinetic precog with the ability to predict and potentially heal a fellow's heart attack, is my favorite yet. Four stars.

Thin Edge, by Johnathan Blake MacKenzie

Author Randy Garrett is back under the pseudonym he prefers when he writes about life in the asteroid belt. This latest piece is about a Belter who is killed by Earthers for the secret of the super strong cording used for rock towing, and about the other Belter who comes to Earth looking for revenge.

It's written with some facility, but the Belters are always too clever and the Earthers too dumb. A low three or a high two, depending on your mood.

All right! It's time to tabulate the data for December!

Analog finished in the middle of the pack with 2.8 stars, above F&SF (2.1) and Fantastic (2.2), but below Galaxy (3.2), Amazing (3.2), and New Worlds (3.2), not to mention last month's issue of Gamma, which I didn't get to until this month (3.3).

There were 44 pieces of fiction between the seven magazines, four of which were written by women. 9% is fairly standard these days, sadly. I'm not sure what's causing the decline, though the numbers were never that much better.

Next up, we'll be covering the UK's newest SF TV show, and beyond that, 1963's Galactic Stars!

Stay tuned.

[The party's still going on at Portal 55. Come join us for real-time conversation!]

![[May 30, 1964] Every journey begins… (Apollo's first flight!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640530apollo-672x372.jpg)

![[August 29, 1963] Why we fly (August Space Round-up)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/630829astronauts-672x372.jpg)