by Erica Frank

When I heard about the new movie, The Satan Bug, I was excited. I have a deep interest in the occult and "lunatic fringe" religions, so I was looking forward to something exotic. I expected it'd be a horror movie with no real research behind it, but I hoped for a verse or two of Aleister Crowley's poem, Hymn to Satan, or perhaps a mention of Anton Lavey's occult workshops in San Francisco.

Maybe it involves alchemy? An evil sorcerer's laboratory? Souls extracted from bodies and poured into a beaker?

Alas; it was not to be. Once I saw the trailer, I realized this is not a story about a giant demon-possessed insect, nor is it a hellish romance inspired by Roy Orbison's song, With the Bug. Instead, it's a mystery-thriller centered around a bioengineered killer disease.

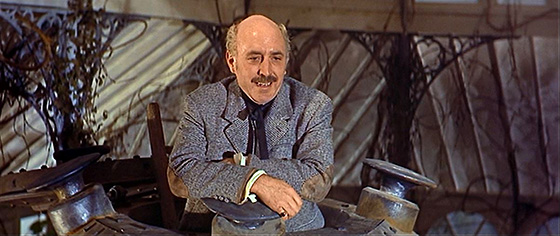

Middle-Aged Men in Suits

The story opens in a remote government scientific laboratory with extensive security measures. (Station 3 is "the most secret chemical warfare establishment on this hemisphere," we discover later.) Mr. Reagan (pronounced ree-gan, not ray-gan like the actor from last year's The Killers) is the "Washington guy." He arrives by helicopter and gets checked in at the gate, and the guards know him personally. Doctor Ostrer is just leaving as Reagan arrives, but arranges to speak with him in the morning. Reagan goes through multiple checkpoints inside as well. The actual lab has thick vault doors with a timer at night; there's no way to get in once they shut.

Three doctors are present: Doctor Baxter, who is in charge, Doctor Hoffman, and Doctor Yang. I hoped this wouldn't be a case of "the Asian fellow is the villain" – and it was not! Instead, we see Doctor Yang for less than thirty seconds and he never appears again.

After showing off the security measures for several minutes, we get a moment of suspense: Reagan tells Dr. Baxter that Washington is worried. Doctor Baxter points to the flask on his desk and says, "What they're really worried about is that." Reagan asks him to get some rest, and warns him that mistakes could be worse than deadly here.

We don't yet have a name for the red-topped flask, just the awareness that a very tired scientist is staring at it in frustration.

By morning, although they don't know all of this yet, Reagan is dead, Ostrer is dead, Baxter is dead, several flasks are missing, and they've called in a special investigator: Lee Barrett. He's a former US Intelligence officer who quit because "war had aged him so fast" he felt "too old to play with toys." Barrett is a rebel, an extremely competent man who doesn't cooperate with authority. Coincidentally, he formerly worked at Station 3.

The Handsome Hero

The subterfuge of Barrett's introduction is a delightful lagniappe of a spy-thriller story: To bring him into an active case, first they had to test his loyalty with a fake job from the World Peace Organization: "Deliver this flask of botulinus vaccine–don't ask how we got it–to this address in Europe." Barrett is very clever and immediately spots the scam: Vaccines aren't stored at Station 3 and he personally knows the loathsome fellow who's behind the World Peace Organization.

Once he's established as "loyal, although insubordinate," he's brought to Station 3, where he chats with one of the security guards before looking at the crime scene. This shows that Barrett has true investigator talents: He knows who notices the details that will matter, and he trusts Johnson's judgment.

Jonhson: "Mr Tasserly says, and Mason, he swears, that nobody got into E Lab. But I don't think Reagan committed suicide in there." Barrett agrees.

Barrett quickly establishes how the murderer escaped, and realizes he must've gotten in through the crates of "lab equipment" that came in yesterday. That means there was inside help, but sorting that out can wait. The real risk is not the lives of the base personnel, but the release of the chemical weapons being developed in E Lab. Dr. Hoffman insists the lab must be destroyed immediately, before opening the vault doors.

Our Villain: A Small Jar

Hoffman first discusses the dangers of the previously mentioned botulinus. He explains, "We have 1200 grams in six flasks. If ten grams of it were allowed to contaminate a city, that city is a morgue in four hours. It is an… ideal weapon, God forgive the phrase, because it destroys only people. And it oxidizes itself, in effect, dies–disappears–after eight hours."

Any persons with medical training should be warned not to laugh, as the music here indicates tension and danger. A virus that vanishes literally overnight cannot reach all the people in a city unless the initial distribution is perfectly and widely dispersed; air does not instantly reach all places in a city. After an initial tragic wave of deaths, people hiding indoors would avoid the rest of the attack. People driving to hospitals might never arrive, and not have the chance to infect anyone else in the few hours they have. It would indeed be a super-weapon, but not the catastrophic one the movie seems to imply.

Such a virus could never happen in nature, as it would kill its host and then die itself. The disease cannot spread by normal routes–eight hours is not a very long contagious period, if it can be spread by bodies. Four hours for spreading via a living host is even less time.

Barrett points out this means the base is safe; the vault door was closed last night. Dr. Hoffman then reveals a new danger: "It is only three weeks since Doctor Baxter refined it, and only three days since he communicated its existence to anyone." Another chemical weapon, an airborne virus, but unlike botulinus, this one is "self-perpetuating, indestructible," and may last forever. "To this virus," he says, "we have given a highly unscientific name, but one which describes it perfectly: The Satan Bug."

Hoffman continues: "If I took the flask that contained it and exposed it to the air, everyone here would be dead in a few seconds. California would be a tomb in a few hours. In a week, all life, and I mean all life, would cease in the United States. In two months, two months at the most, the trapper in Alaska, the peasant from the Yangtze, the aborigine in Australia–dead. All dead, because I crushed the flask, and exposed a green-colored liquid to the air."

This must be some newfangled definition of "green" with which I am unfamiliar. But you can still tell it's worse than the other flasks of deadly disease, because the cap is red.

Satan Must Be Anti-Science

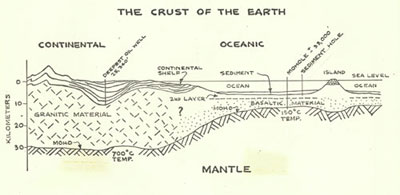

At this point, I questioned Dr. Hoffman's medical credentials, because the idea of an airborne virus that would kill all eighteen million people in California in hours is ridiculous. It really doesn't matter how deadly the disease is, nor how resilient: the air just doesn't move that fast.

California spans over a thousand miles from north to south. At five hours–a reasonable estimate of "a few"–the bug would need to travel at 200 mph to cover the state. I don't know where my readers reside, but I assure you: California is not normally wracked by 200-mile-an-hour winds. Perhaps he means "if it started in the middle." In which case, we only need 100 mph winds, which are also exceedingly rare. Or we could say that 20 hours is "a few," but still short enough from a day that he wouldn't use that. To cover 500 miles in 20 hours, the bug needs to travel at 25 mph. Certainly we get winds that fast… but not constantly, and not covering the full length of the state.

Moving on to his claim about a week to cover the entire United States: 2800 miles wide, 168 hours: 16.666 miles per hour. (AHA! There's our Satan reference!) But the wind does not consistently blow at that speed, nor do breezes from one area reach every other part of the country. Winds from the California coast reach Oklahoma and New York, sometimes quickly – but they hardly get to Montana at all.

The Jetstream on April 11, showing the cause of one of the worst tornado incidents in history: 12 tornadoes touched down in 4 hours; over 50 people were killed and several hundred injured.

Danger! Action! Gunshots! (but no blood)

Having established the extreme danger, our hero Barrett (you know he's the hero; he's younger and better-looking than all the other men in the movie) volunteers to go into the lab to find if there's a spill. He makes sure the other men are armed and ready to shoot him if he is exposed. How they're going to kill him and close the glass doors if the disease kills "in seconds," I don't know. But it doesn't matter, because of course the disease has not been spilled in the lab; it's been stolen. They identify the mastermind behind the theft as a Mr. Ainsley, a mysterious wealthy man who vanished several months ago.

Thus begins the chase-and-action portion of the film: tracking down leads, car chases, abductions, and a hint of romance. (An old friend of Barrett's shows up; she sometimes has a useful suggestion, but mostly serves to give him someone to explain what he's figured out.) One flask of botulinus is rigged with a bomb, somewhere in Los Angeles. The men assigned to help Barrett mostly die, because he is faster, smarter, and luckier than they are. Ainsley's goons assigned to kill Barrett mostly die, for the same reasons. The red-topped flask changes hands a few times, but every time Barrett or his allies get it, the villains quickly recover it.

How to search a baseball stadium for a bomb: assign one cop per row and have them walk through the seats. Also, you check the results by yelling, because nobody carries a radio on a search.

At one point, Barrett, his girlfriend, and a couple of lawmen are captured. I have no idea why they're not all immediately killed–the goal is to release a virus that kills thousands nearly instantly with the threat of killing millions as leverage… why would they hesitate at killing a small handful of people who might escape to undermine their plans? You'd think that an evil mastermind would find less squeamish goons.

Does Everyone Die?

As one might expect, the plans are foiled. Ainsley is revealed to be Someone We've Known All Along, and there is an energetic fight scene for control of the deadly flask. This takes place in an out-of-control helicopter, with both people and the flask at risk of falling over Los Angeles. Our hero prevails! (I hope I haven't spoiled the ending for you, but he really is just too pretty to die by an evil plot.) Of course he knows how to fly a helicopter (he admits he's "a little rusty") so, he heads off to LAX to be reunited with his team.

Autopsy Report

In the end, while there's nothing particularly wrong with this film, there's nothing outstanding about it either. The science at its core is deeply flawed, reduced to being a plot gimmick instead of anything an educated person could believe possible. The cast is: one handsome hero; one good-looking ladyfriend; a swarm of distinguished white guys in suits (the cops/federal agents); a swarm of somewhat-ugly white guys in casual clothes (the goons); a sparse handful of non-white people who mention a few details and then vanish; one villain who's pretending to be one of the good guys. None of them is unique or even memorable. The plot is so simple that there's no room for nuance: if the hero succeeds, all is well; if he fails, all human life will be destroyed.

The poster lies: this is not about "the ultimate evil." There is no evil at all in the "Satan bug" itself; it's a mindless organism with no motivation of any sort. All the evil is in the men trying to use it for gain… and they don't fail due to incompetence or greed. Good triumphs, evil fails–because "good" happens to include the former special ops agent with a law degree who can take over a helicopter in mid-flight and safely land it. This is not a lesson about the folly of evil; it's a lesson that talented, handsome heroes can beat aging, sour-faced villains.

If you enjoy this kind of action-thriller with the barest hint of science fiction, this movie won't disappoint. The acting is good, if a bit emotionless (these are stoic government agents, for the most part); the settings realistic; the action well-paced. But if this is not your normal fare, it won't convince you to seek out similar films.

Three stars out of five.

Our last two Journey shows were a gas! You can watch the kinescope reruns here). You don't want to miss the next episode, April 25 at 1PM PDT featuring flautist Acacia Weber as the special musical guest.

![[April 20, 1965] Less Satanic Than Expected (John Sturges' <em>The Satan Bug</em>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/650422_movieposter-672x372.jpg)

![[April 8, 1965] Twisted but Classy (Mario Bava's "Blood and Black Lace")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/BBLposter-672x372.jpg)

![[March 6, 1965] Breaking Up Is Hard To Do (<i>Crack in the World</i> and Other Planet-Destroying Movies)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/PDVD_000-672x372.jpg)

![[October 10, 1964] Drop The Bomb and We All Go Down (Sidney Lumet's <I>Fail Safe</I>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/theend-672x350.jpg)

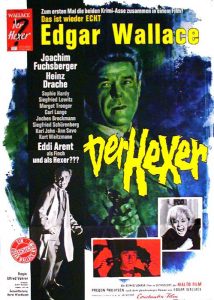

![[September 26, 1964] A Mystery Mastermind Double-Feature: The Ringer and The Death Ray of Dr. Mabuse](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/hexer-499x372.jpg)

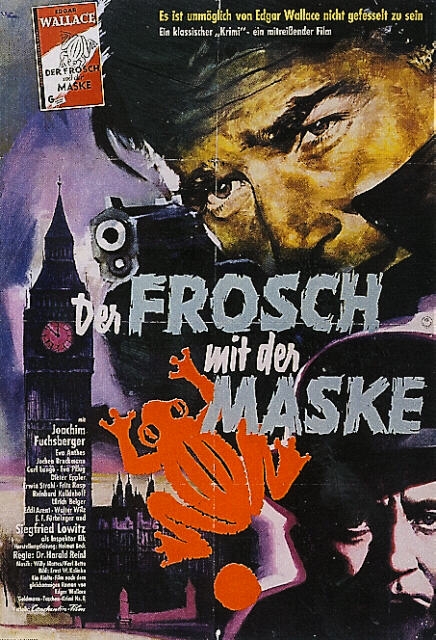

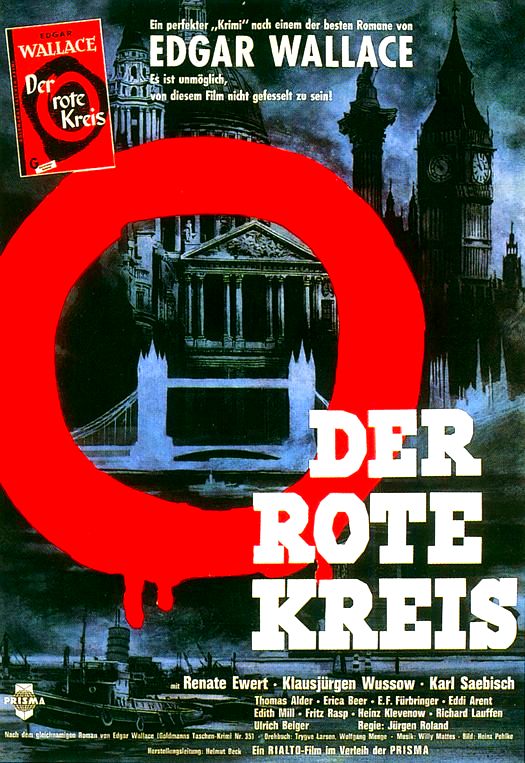

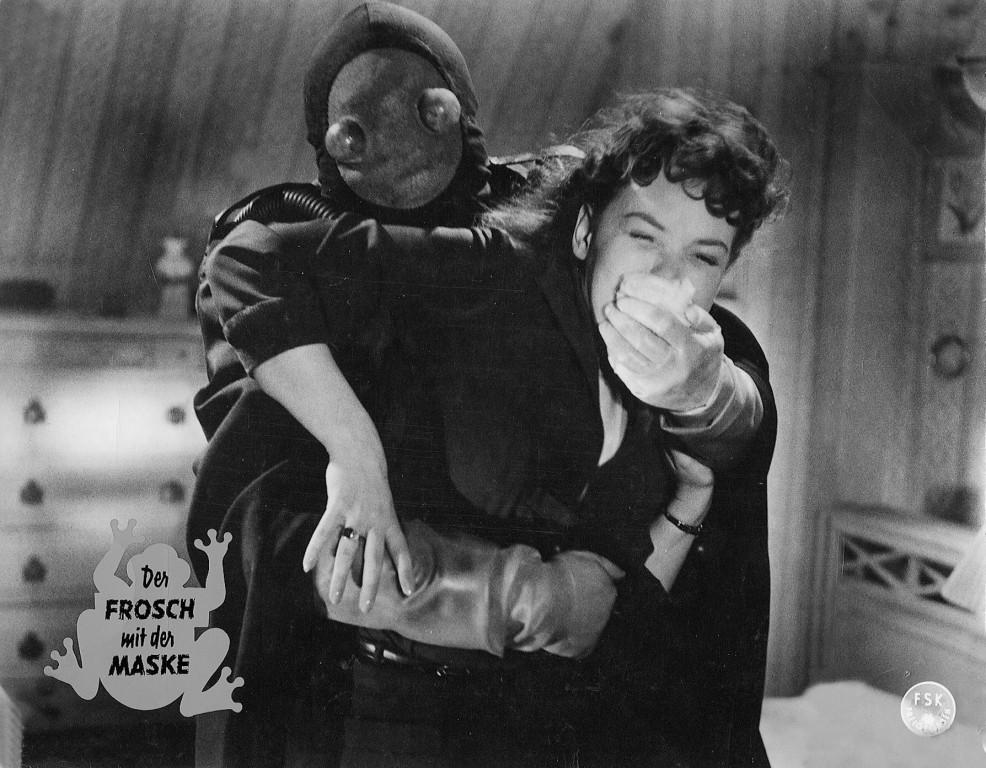

Der Hexer (The Ringer) is the twentieth Edgar Wallace adaptation produced by Rialto Film and one of the best, if not the best movie in the series so far. The Ringer is a pure delight and a distillation of everything that has made the Edgar Wallace series so successful. The balance of humour and thrills is just right and The Ringer will have you both rolling on the floor with laughter and on the edge of your seat with suspense. There are nefarious crimes, a mysterious figure – for once not the villain – whose true identity is not revealed until the final reel and a twisting and turning plot that still has a twist or two in store, even after the Ringer has been unmasked.

Der Hexer (The Ringer) is the twentieth Edgar Wallace adaptation produced by Rialto Film and one of the best, if not the best movie in the series so far. The Ringer is a pure delight and a distillation of everything that has made the Edgar Wallace series so successful. The balance of humour and thrills is just right and The Ringer will have you both rolling on the floor with laughter and on the edge of your seat with suspense. There are nefarious crimes, a mysterious figure – for once not the villain – whose true identity is not revealed until the final reel and a twisting and turning plot that still has a twist or two in store, even after the Ringer has been unmasked. The Ringer is based on Edgar Wallace's 1925 novel The Gaunt Stranger and its 1926 stage version The Ringer, though the literal translation of the German title would be "The Witcher". It's certainly apt, for the titular character is not just a master of disguise, but also has nigh sorcerous abilities to evade Scotland Yard's finest.

The Ringer is based on Edgar Wallace's 1925 novel The Gaunt Stranger and its 1926 stage version The Ringer, though the literal translation of the German title would be "The Witcher". It's certainly apt, for the titular character is not just a master of disguise, but also has nigh sorcerous abilities to evade Scotland Yard's finest. Unbeknownst to the killers, the murdered woman was Gwenda Milton, the younger sister of Arthur Milton, the vigilante known only as the Ringer for his uncanny ability to disguise himself as anybody he pleases. Years ago, Arthur Milton had given up his career of vigilantism and retired to Australia, far beyond the reach of the British law. But now he is back to take revenge on the murderers of his sister. Of course, both the villains and Scotland Yard are only too eager to capture the Ringer. There is only one problem. No one knows what he looks like.

Unbeknownst to the killers, the murdered woman was Gwenda Milton, the younger sister of Arthur Milton, the vigilante known only as the Ringer for his uncanny ability to disguise himself as anybody he pleases. Years ago, Arthur Milton had given up his career of vigilantism and retired to Australia, far beyond the reach of the British law. But now he is back to take revenge on the murderers of his sister. Of course, both the villains and Scotland Yard are only too eager to capture the Ringer. There is only one problem. No one knows what he looks like.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the latest movie in the other great West German thriller series. For while the Dr. Mabuse series has been very good at reinventing itself in the five movies made post WWII (plus two made during the Weimar Republic) so far, the latest instalment Die Todesstrahlen des Dr. Mabuse (The Death Ray of Dr. Mabuse) shows definite signs of the series going stale.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the latest movie in the other great West German thriller series. For while the Dr. Mabuse series has been very good at reinventing itself in the five movies made post WWII (plus two made during the Weimar Republic) so far, the latest instalment Die Todesstrahlen des Dr. Mabuse (The Death Ray of Dr. Mabuse) shows definite signs of the series going stale.

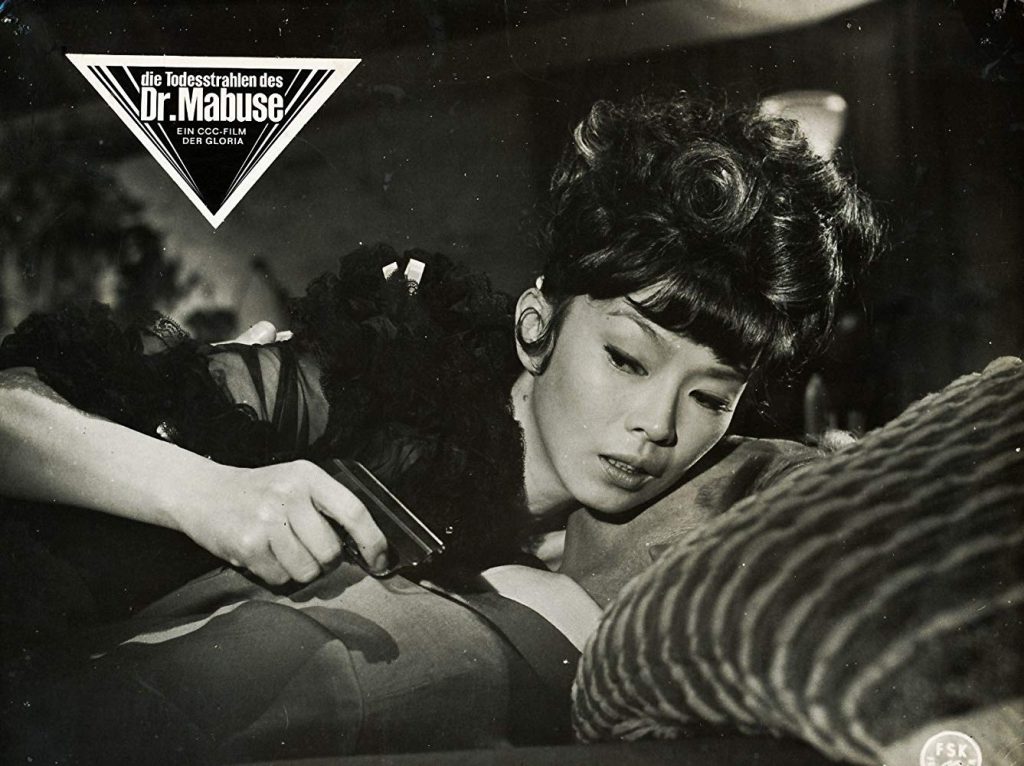

Not long after Pohland's disappearance, Anders is given a new assignment – to investigate spy activities in Malta, where a scientist named Professor Larsen is working on an invention that will change the world. And that invention just happens to be a death ray. Anders no more thinks that this is a coincidence than the audience does. So he hastens to Malta, taking along Judy (former Miss Greece Rika Dialina), one of his many girlfriends, to pose as a newlywed couple on their honeymoon.

Not long after Pohland's disappearance, Anders is given a new assignment – to investigate spy activities in Malta, where a scientist named Professor Larsen is working on an invention that will change the world. And that invention just happens to be a death ray. Anders no more thinks that this is a coincidence than the audience does. So he hastens to Malta, taking along Judy (former Miss Greece Rika Dialina), one of his many girlfriends, to pose as a newlywed couple on their honeymoon.

![[July 26, 1964] Yesterday's Tomorrows (<i>First Men in the Moon</i> and Other Steam Science Fiction Movies)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/first-men-in-the-moon-trailer-title.jpg)

The super-submarine Nautilus; a thing of beauty.

The super-submarine Nautilus; a thing of beauty. Old Blue Eyes in a tiny role as a piano player.

Old Blue Eyes in a tiny role as a piano player.

![[July 10, 1964] Greetings from the Red Planet (The Movie, <i>Robinson Crusoe on Mars</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/640710b-672x372.jpg)

![[June 24, 1964] Death Has No Master (Roger Corman's <i>The Masque of the Red Death</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/masqueposter-672x372.jpg)

![[June 10, 1964] What washed up (<i>Horror at Party Beach</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640610horror-459x372.jpg)

![[June 4, 1964] Weird Menace and Villainy in the London Fog: The West German Edgar Wallace Movies](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640604The_Green_Archer-672x372.jpg)