by Gideon Marcus

[Today's article is a true treat — a full three Journeyers caught the latest science fiction flick, an import from Britain. We hope you enjoy this, our first review en trio…]

Think "science fiction" movie, and you might conjure up a rubber-suited monster or a giant insect or perhaps a firework-spouting bullet of a spaceship. Once in a great while, we get a Forbidden Planet or The Time Machine — high quality films but no less fantastic in subject matter.

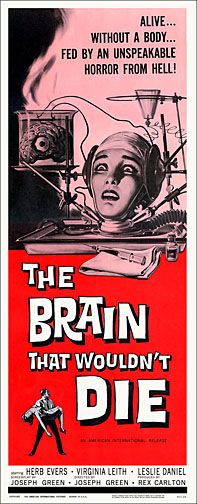

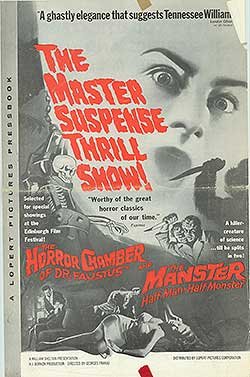

Now picture a "horror" film. Perhaps it involves the supernatural or monstrous terror. Maybe it's one of Hitchcock's genre-creating numbers like Psycho or The Birds. Often, the lines between SF and horror are quite blurry as in films like Wasp Woman and The Day Mars Invaded Earth. After all, the unknown can be quite terrifying, and what is SF but an exploration of the unknown?

The Mind Benders is a new British film that straddles the line between science fiction and horror and yet bears no resemblance to any of the examples described above. It is, in fact, a movie set in the now and portraying modern (if cutting edge) science. And the horror depicted is all the more jarring for its common nature.

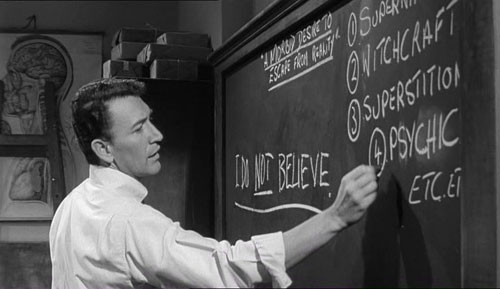

Two nascent sciences are the basis for this movie. One is that of brainwashing, the technique of forcibly altering someone's beliefs, generally through some kind of torture, privation, or other constant pressure. This is the sort of thing covert agencies are good at, but you can also see it on a national level, through effective use of propaganda and fear. The other science is sensory deprivation. Several experiments have been done into the effects of having all of one's senses dulled. A subject is suspended in warm water, in the dark, unable to smell, taste, or hear anything. The results include disorientation, agitation, and hallucination.

The film starts with aged sensory deprivation scientist Sharpey, paranoid and in a daze, taking his own life by throwing himself off a moving train. In his satchel are thousands in pound notes. Army Intelligence Major Hall is called in to investigate, and he quickly determines that Sharpey had recently sold secrets to the Communists. Ready to brand the scientist a traitor and close the case, he is persuaded by Sharpey's colleague, Longman, that Sharpey was a patriot, and that any lapse in loyalty must have been a result of a recent sensory deprivation experience.

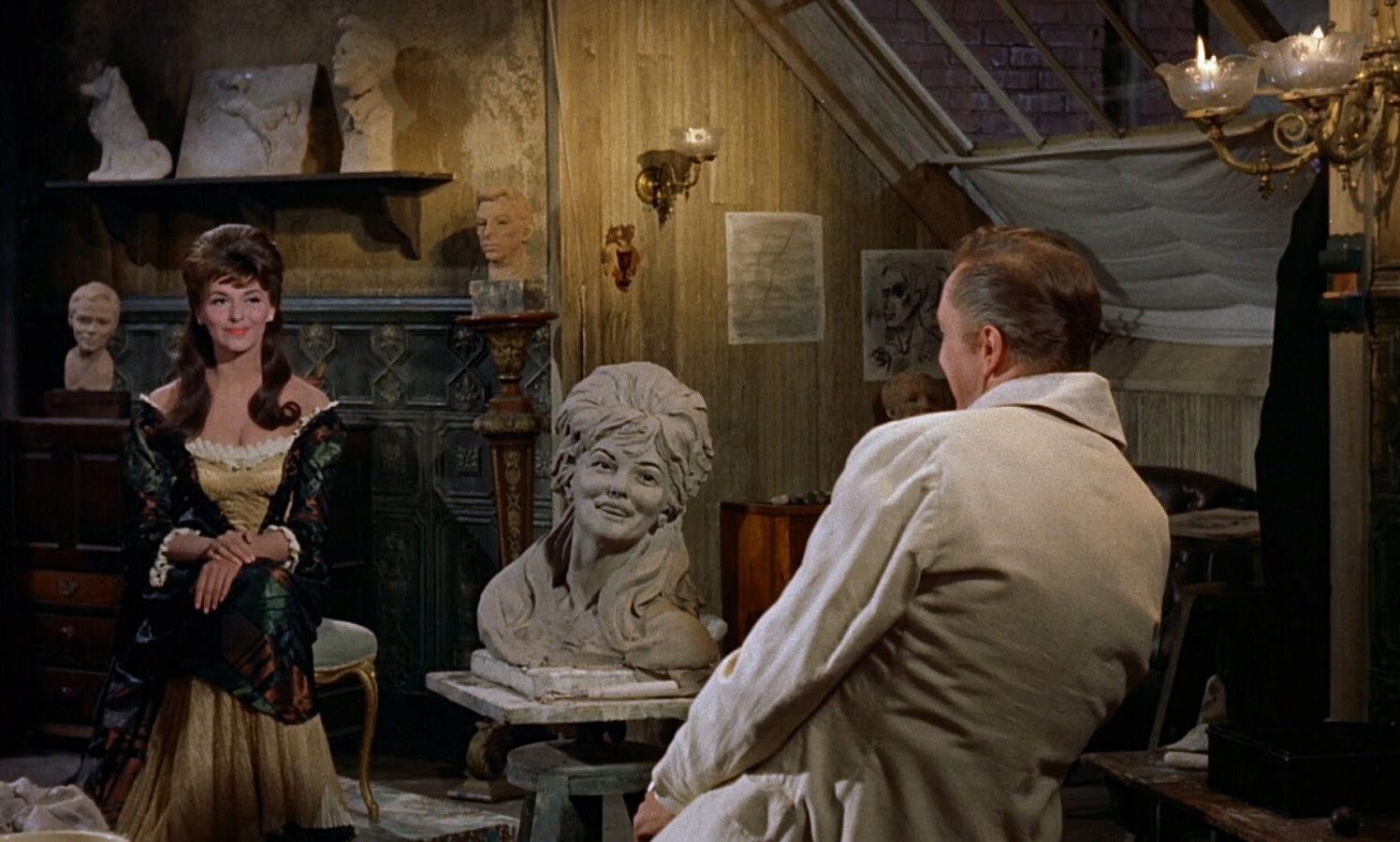

Longman is introduced as a loving husband and a doting father, humorous and cynical, and possessed of a tremendous fear of sensory deprivation after several terrifying experiments. Nevertheless, he offers himself up for a final test, a full eight hours in the deprivation tank, to show that it does something to a person. Having shown that, Longman can prove that Sharpey was not responsible for his treasonous activities.

Hall agrees, and with the assistance of a third colleague, Tate, who has not been a subject, conducts the experiment on Longman. Floating alone and in the dark, the scientist suffers countless subjective hours of anguish (though only a third of a day passes outside), and at its end, he is reduced to a blank, malleable state. Hall recognizes this condition — a broken man in this state is easily brainwashed. But this is not enough. They must compel Longman to engage in activity completely counter to his nature, to shake him of his strongest-held belief. So, they pull Longman from the tank, dazed and vulnerable.

And with a just a few choice words, they cause him to hate his wife, Oonagh.

Yet, due to the circumstances under which they effect their plot, it is unclear that they have succeeded. Longman is released, the experiment seemingly a failure. So ensues six months with Oonagh, increasingly pregnant, incessantly nagged and belittled until she is a shell of herself. Longman is also a changed man, bitter and resentful, completely unaware of what has been done to him. That Oonagh endures for so long is British "stiff-upper-lipism" carried to its absurd limits. That this state of affairs goes unnoticed for half a year is because Tate, himself in love with Oonagh, cannot bring himself to check up on the ruined couple.

Blessedly, once Hall does find out, he is (with no little difficulty) able to reverse the process. The marriage is repaired and Sharpey's name is cleared. But, by God, at what price?

As a movie, Benders is a success, cinematographically compelling and with superb acting. What makes this horror so effective is its utter plausibility, and as a family man, myself, the situation struck me at my core and left me shaken.

It's not a perfect film. I imagine 15 minutes could have been cut with no great loss. And the overlong period of estrangement runs a bit beyond the lengths of credulity, and yet… is it not all too common for women to suffer indefinitely with men they once loved in the hopes that things might, one day, return to how they were?

I couldn't watch The Mind Benders again, and I can't recommend it to those who will find the subject matter unbearable, but I must recognize the skill with which the movie was crafted. Four stars.

by Lorelei Marcus

I didn't have very high hopes going into The Mind Benders, thinking it was going to be another campy science fiction movie using a shaky camera for special effects. Instead, I got a rather dark film about the capacity of the human mind and its reaction to prolonged isolation. The concept was very fascinating, and the story even more haunting from being based on real experiments. The acting was excellent, even too real at times.

However, it was not all good. The movie was much too long, and I believe it could benefit a lot from having a few of the “man bicycles around the city” scenes taken out. Even with the interesting premise, it also lulled at times, and I found myself wondering when the movie was going to end. Even so, I would give this movie three stars out of five. It wasn't anything super special, but it wasn't bad either.

This is the Young Traveler signing off.

by Natalie Devitt

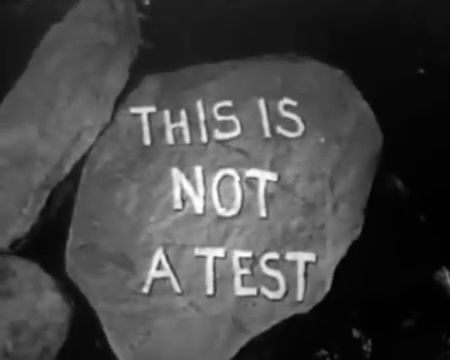

The tagline for The Mind Benders described the film as being “perverted… soulless! The most dangerous and different motion picture ever brought to the screen!” So, naturally that piqued my curiosity. What I ended up with was a pretty ambitious story about brainwashing.

Luckily, I’m a sucker for a story about brainwashing.

Overall, the film was well-shot with believable acting. The movie did run out of steam a little towards the end, and I’m not totally sure that I bought the ending, but it was an otherwise effective sci-fi/thriller. The film’s somewhat disturbing plot and dream-like qualities kept it on my mind long after it ended. Three and a half stars.