by Gideon Marcus

You've almost assuredly heard of Radio Corporation of America (RCA). They make radios (naturally), but also record players, televisions, computers. They have produced the foundations of modern consumer electronics, including the color television standard and the 45 rpm record. And now, they've really outdone themselves: they've created cassettes for tape recording.

Until now, if you wanted to listen to music or a radio show, you had to either buy it as a pre-recorded album or record it yourself. The only good medium for this was the Reel to Reel tape recorder – great quality, but rather a bother. I've never gotten good at threading those reels, and storing them can be a hassle (tape gets crinkled, the reels unspool easily, etc.). With these new cassettes, recording becomes a snap. If the price goes down, I'll have to get me one.

What brought up this technological tidbit? Read on about the March 1962 Analog, and the motivation for this introduction will be immediately apparent.

His Master's Voice, by Randall Garrett

The RCA-themed title for Garrett's latest is most appropriate. Voice is the next in the exploits of the ship called McGuire. As we learned in the first story, McGuire is a sentient spacecraft that has imprinted on a specific person – an interplanetary double-agent working for the United Nations. Like the last story, Voice is a whodunnit, and a bit better handled one than before, as well. Garrett's slowly improving, it seems. Three stars.

Uncalculated Risk, by Christopher Anvil

Every silver lining has a cloud, and every scientific advance is a double-edged sword. Anvil likes his scientific misadventure satires. This one, about a soil additive that proves potentially subtractive to the world's arable land, is preachy but fun. Three stars.

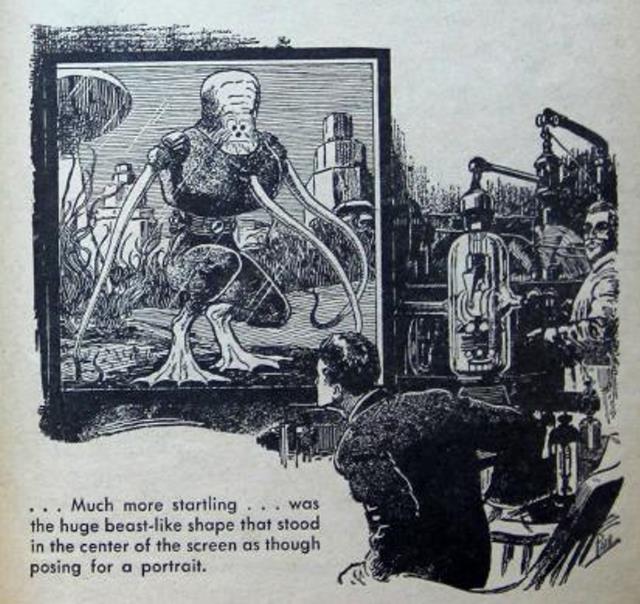

Rough Beast, by Roger Dee

The most fearsome carnivore in the known universe breaks free from an interstellar zoo and runs amok on one of the Floria Keys. Can a group of scientists, a host of pacifist aliens, one cranky moonshiner, and a nervous tomcat stop the creature in time? A shaky, over-adjectived beginning, but the rest is a lot of fun (and I guessed the ending moments before it was revealed). Four stars.

The Iron Jackass, by John Brunner

Brunner is a prolific author whose work I've rarely encountered, perhaps because he's based across the pond; Rosemary Benton plans to review his newest book next month. Jackass is a fun tale involving an off-world steel mill, the Central European miners who work it and shun automation, and the robots that threaten to put the miners out of business. I saw shades, in Jackass, of the recent Route 66 episode, First-Class Mouliak, which took place in a Polish steel community in Pennsylvania. Three stars.

Power Supplies for Space Vehicles (Part 2 of 2), by J. B. Friedenberg

Mr. Friedenberg has returned to tell us more about motors of the space age. This time, it's all about solar-heated turbines, and it's just about as exciting as last time. I give credit to Friedenberg for his comprehensiveness, if not his ability to entertain. Two stars.

Epilogue, by Poul Anderson

Anderson is going through a phase, digging on somber, after-the-end stories (witness After Doomsday). His latest novella takes place fully three billion years in the future, after humanity has destroyed itself and self-repairing and replicating machines have taken over. Sparks fly between silicon and carbon-based life when a crew of time-lost humans returns to its mother planet for one last farewell.

An excellent idea, and Anderson's typically deft characterizations, are somewhat mitigated by robots that are a bit too conventional in their culture (no matter how radical their physiology), and by the fact that, in the end, Epilogue becomes a straight technical puzzle story. Four stars.

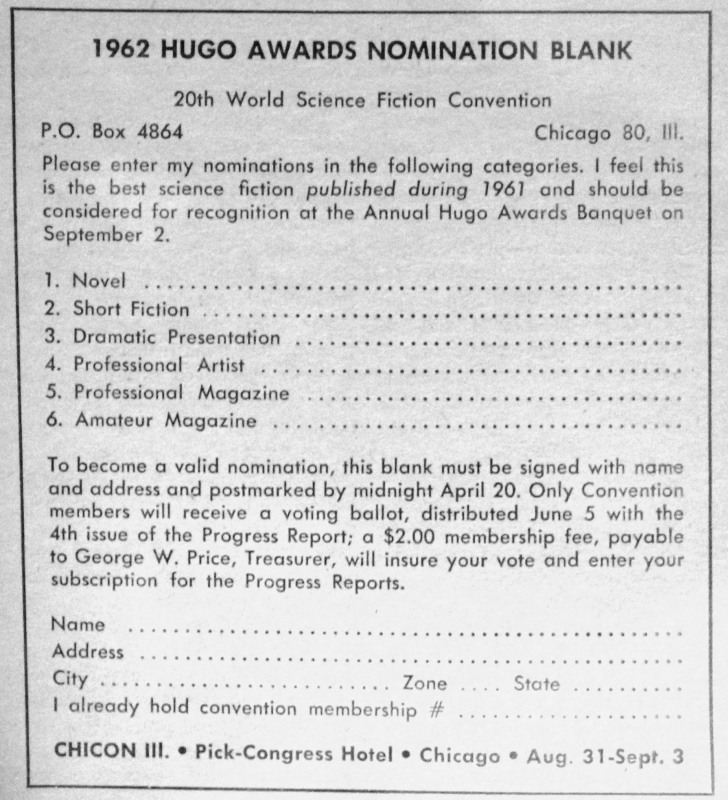

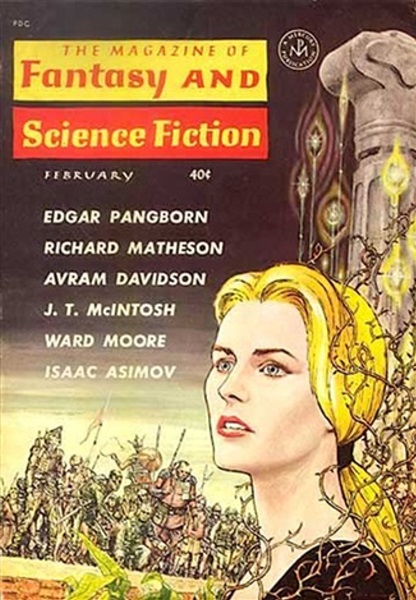

The Numbers

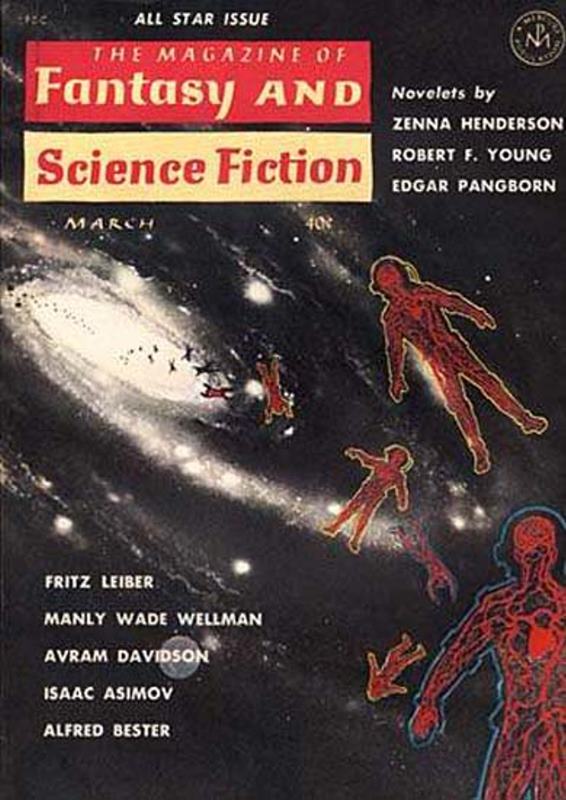

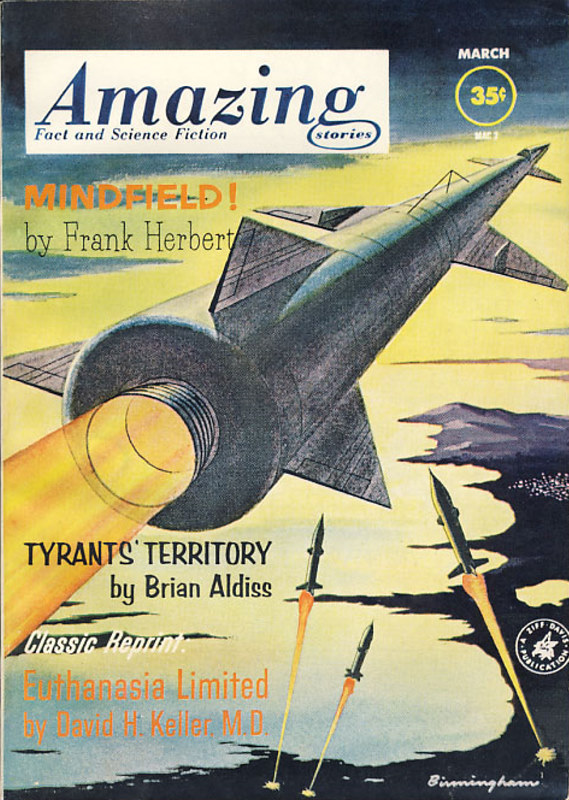

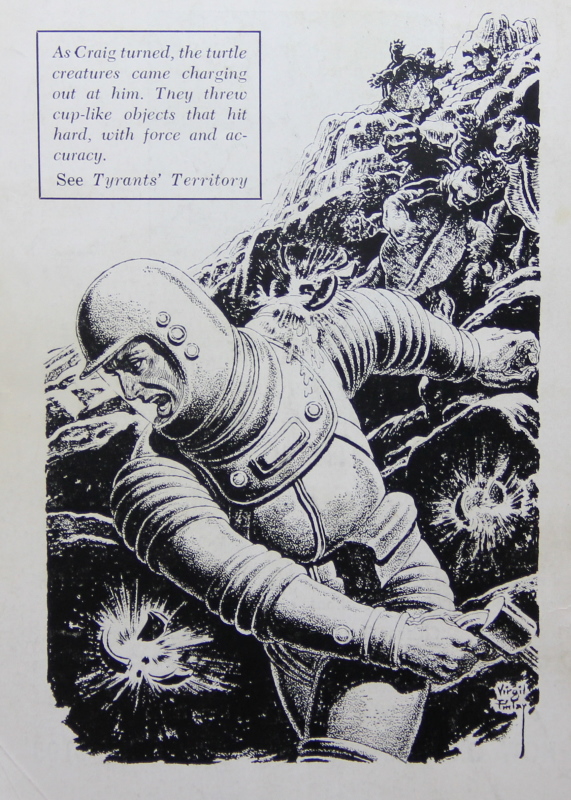

This all adds up to a 3.2-star issue, respectable for any magazine and downright shocking for Analog. This makes it the #2 digest for March 1962 (behind F&SF at 3.8, and ahead of IF (3.2), Amazing (2.8), and Fantastic (2.5). Women once again wrote just two of this month's pieces, one of which was a tiny poem. The best stories came out in F&SF, the best of which is hard to determine – the Pangborn, the Young, or the Wellman?

Stay tuned for Fantastic to start the exciting month of March!