[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Gideon Marcus

My father used to say that the road to drug abuse didn't start with pot, or smoking, or even alcohol.

"It all begins with milk," he'd say.

The funnel that leads to a life of science fiction fanaticism is not quite so broad, but there sure are a lot of entry points. For instance, one can't read the newspaper without some update on the Space Race or a new drug. Sci-fi movies, while often terrible, are ubiquitous. Science fiction novels are starting to take off just as the monthly digests are at their nadir. Marvel Comics has launched several new sf-related titles. Conventions are increasing in number. Yes, the tentacles of fandom are many, indeed.

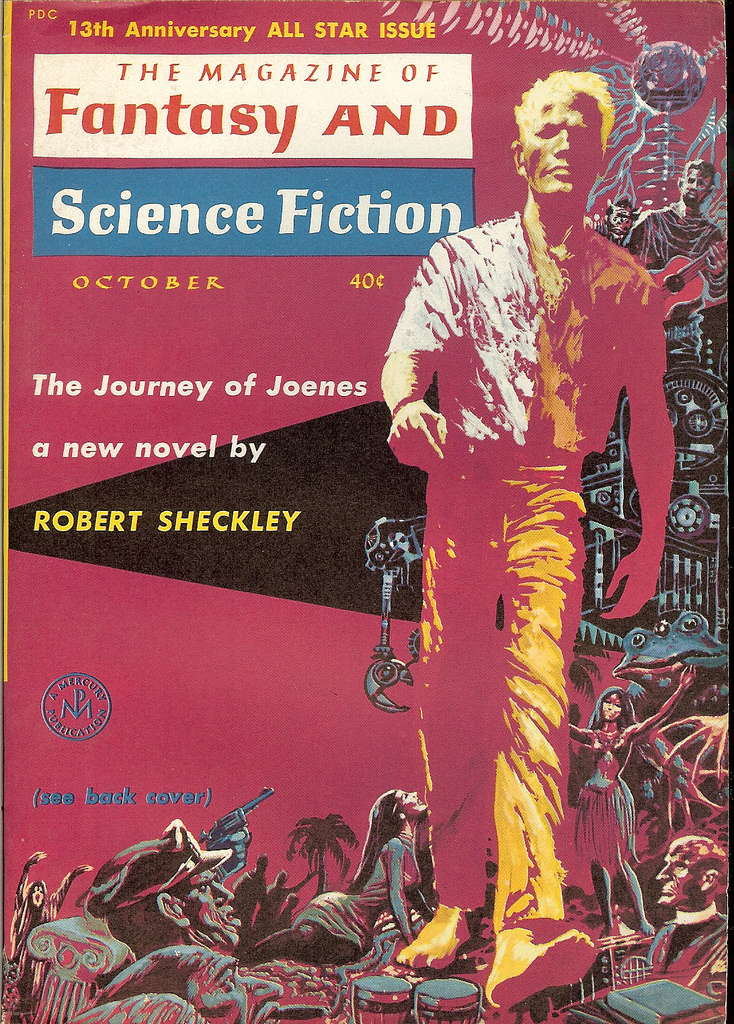

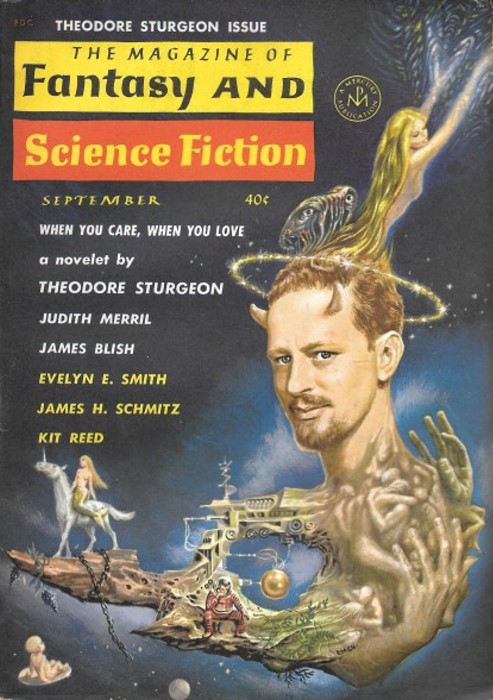

My introduction was the October 1950 debut of Galaxy magazine. Sure, I'd read and watched some science fiction before then, but it hadn't grabbed me consistently. Galaxy was pure quality in every issue, and I soon bought an addiction…er…subscription. Well, there were so many other magazines on the shelf next to Galaxy, surely some of them must be good, too, I reasoned. By 1954, I was regularly also reading Fantasy and Science Fiction, Astounding, Imagination, Fantastic Universe, Satellite, and Beyond. Let me tell you — keeping up was a chore! I was almost glad to have the field winnow a bit toward the end of the decade.

In 1958, I began writing this column, and my reading became more disciplined, more with an eye toward providing content to my readers (who numbered about three at the time; thank you, Stephanie, Janice, and Vic). The trick then was to ensure I had enough material to fill 10-15 articles a month. Three magazines and the odd space shot weren't enough to do the trick. So I started reading the science fiction novels as they hit the newsstands. Not all of them, mind you, but the ones that looked interesting. I began going to the cinema with the Young Traveler for all of the sf flicks, good, indifferent, and (too often) bad. The Twilight Zone debuted in 1959, and that became a regular viewing experience.

There's nothing a fan likes more than meeting other fans, so of course, attending conventions became a must. And then I wasn't just going to conventions; I became a panelist, a sought out guest. There began to be rumblings that Galactic Journey might be on the ballot for a Best Fanzine Hugo sometime soon, so I broadened my reading material to include other fanzines.

This, then, is my current state…buried under a pile of reading material faced with a daunting publication schedule. Thank goodness many of the Journey's readers have become associates, bringing their unique (dare I say, superior) talents to this ever-burgeoning endeavor.

So this month, I've got a couple of special treats, which I shall provide largely without comment. The first is a fanzine revival by Uberfan Al haLevy. Rhodomagnetic Digest was a stand-out 'zine for several issues in the early '50s. Al revived it this year, and I recently got my hands on the second issue. Highlights include the converage of the Labor Day "Nonvention," a sizeable California gathering for the folks who couldn't make Chicon III; and a comprehensive encyclopedia of Tolkein's hobbits. The latter looks to be first in a series, and I'm certain Middle Earth fans will find it useful.

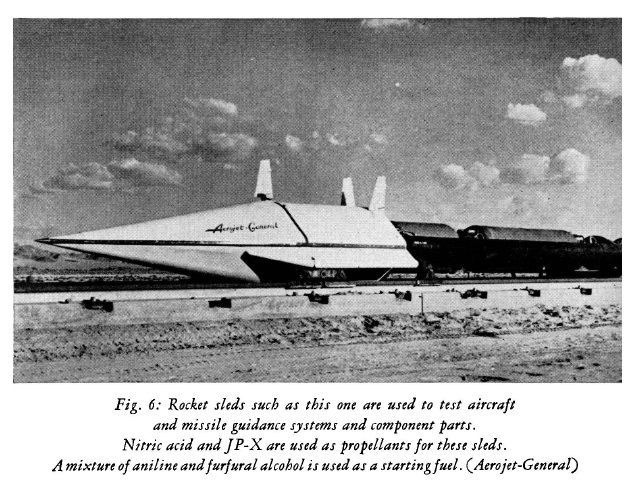

Present #2 is a science fiction movie magazine, Spacemen . I hadn't even been aware of its existence, but a friend left his copy of Issue 5 here last weekend, and I found it interesting enough to share. It's a retrospective issue, full of lore going back several decades, the most compelling of which (to me) was the interview with Buster Crabbe about his work portraying Buck Rogers, which he did after his stint as Flash Gordon. Lots of good pictures and some fascinating advertisements in the magazine's aft section.

I hope you enjoy these off-the-beaten-path pieces of sf fandom goodness. And if these be the items that tip you from FIJAGDH (Fandom is Just a G-D Hobby) to FIAWOL (Fandom is a Way of Life)…

…welcome aboard!