[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Gideon Marcus

Ah F&SF. What happened to one of my very favorite mags? That's a rhetorical question; Avram Davidson happened. The new editor has doubled down on the magazine's predilection for whimsical fantasy with disastrous (to me) results. Not only that, but it's even featuring fewer woman authors now than Amazing, of all mags. I am shaking my head, wishing this was all some Halloween-inspired nightmare. But no. Here it is in black and white with a forty cent price tag. Come check out this month's issue…but don't say I didn't warn you:

The Secret Flight of the Friendship Eleven, by Alfred Connable

We all know astronauts are lantern-jawed, steely eyed, terse test-pilots. Great for getting the job done, not so great for poetic inspiration. Eleven is the tale of a corps of artistic types selected specifically so as to describe their journeys in more approachable terms. But space has the last laugh.

Every so often, a brand new author knocks one out of the park on the first at bat. This is not one of those cases. For satire to work, it has to be clever, and this is just mundanely droll. One star.

Sorworth Place, by Russell Kirk

It's October, so ghost stories are thoroughly appropriate. This one, however, set in a battered Scottish castle, is neither original nor particularly engaging. Two stars.

Card Sharp, by Walter H. Kerr

I really have no idea what Kerr's poem is about. Even Davidson's explanation is no help. One star.

Hop-Friend, by Terry Carr

Thus begins about twenty pages of relative quality, an island of the old F&SF in a sea of lousiness. Newish author Carr finds his feet with this sensitive and striking tale of first contact between Human and Martian. Introverts can never fathom extroverts, and similarly, xenophobes find xenophiles, well, alien! But extroverted xenophiles, even from different species, are birds of a feather. Four stars (even if Carr's Mars conforms more to older theories of the Red Planet's atmosphere).

Pre-Fixing it Up, by Isaac Asimov

How many rods in a furlong? How many grains in a pennyweight? I have no idea…and with the metric system, it doesn't matter. The Good Doctor explains the ins, outs, and many merits of the new standard that lets you measure everything from an atom to a universe with a series of easily manipulated units. Four stars.

Landscape With Sphinxes, by Karen Anderson

Back into the sea with a Sphinx-themed riddle: What earns four stars at its prime, two stars when it doesn't try, and three stars most of the time? The Anderson family of writers. No matter how good an author one is, it takes more than a promising beginning to make a story. Two stars for this third of a vignette.

Protect Me from My Friends, by John Brunner

There is a fine line between innovation and illegibility. I read Brunner's first person account of an overwhelmed telepath twice (it's short), and I still don't like it. Two stars.

You Have to Know the Tune, by Reginald Bretnor

Another half tale from the fellow we know better as Grendel Briarton (of Feghoot "fame" — and that entry is truly bad this month). Industrialist on the way to Africa hears a tale of the pied bassoonist of the veldt only to find it's likely no legend. Trivial. Two stars.

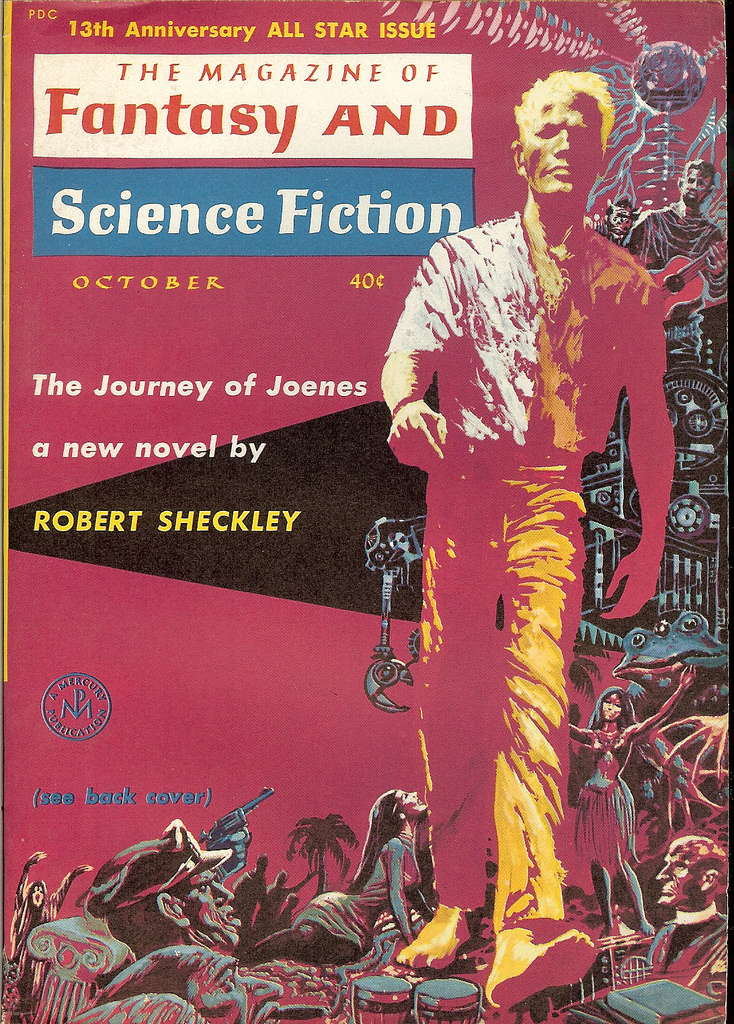

The Journey of Joenes (Part 2 of 2), by Robert Sheckley

As any of my readers knows, no greater fan of Robert Sheckley walks the Earth. His short stories are funny, thought-provoking, chilling, clever — by turns or all at once. In the last decade, he wrote enough to fill six excellent collections, none of which will ever leave my library.

Where he falters is novels. Somehow, Sheckley can't keep the pace for 150 consecutive pages, and the result is, while never bad, never terrific. Cases in point: Time Killer and The Status Civilization. Bob seems to be cognizant of this weakness. In his latest book, The Journey of Joenes he attempts to overcome it by writing a novel composed of short, somewhat independent narratives. The result is something that is, to my mind, no more successful than his previous book-length works. You may, of course, disagree.

Joenes is a pure satire, putatively written in a post-apocalyptic 30th Century Polynesian. It details the life of Joenes, an American-born Tahitian power engineer, who is one of the few to survive the worldwide cataclysm. The tale is told by others: Polynesian historians; excerpts from the memoirs of Joenes' beatnik companion, Lum; edifying tales recorded anonymously.

There is a plot — Joenes comes to the United States, winds up before a Court on the charge of sedition, is sentenced to a mental hospital for the Criminally Insane, flees to become a professor of Polynesian Cultural Studies, goes into government, and ultimately escapes nuclear anhilation. This, however, isn't the point. Rather, we see our own modern culture through a mirror darkly, distorted not just as a satire of our society, but of legend in general. The history of the United States is mixed liberally with that of Ancient Greece. Historical and mythical personages are referenced with equal frequency. It's effectively done, essentially doing for 20th Century America what Homer did for 12th Century B.C. Greece.

Joenes is clearly an attempt by the author to make the philosophical treatise for the 1960s, the equivalent of Stranger in a Strange Land or Venus Plus X. The satire is approachable, even for the layman, and there is some sex in it. Whether it succeeds wildly like Heinlein's piece or fizzles like Sturgeon's, only time will tell.

I can only speak for myself. While Sheckley is always readable, I felt that the joke went on too long, particularly in the latter portions. Perhaps I'm just too close to the subject matter he was aping. In any event, I give Joenes three stars. If this kind of thing is your bag, I suspect you'll rate it more highly.

And that's that for this month. More disappointment in 130 pages than I've seen in a long time, if ever. When I do the Galactic Stars next month, I'm certain F&SF won't be on the list, and that saddens me. Nevertheless, I hope against hope that this is just a phase, and the once proud digest will someday return to its former glory. Time will tell…