[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Mark Yon

Hello all, again.

Being a Brit, I guess it shouldn’t be too surprising that I should start this month with talk of the weather. The cold weather I mentioned in October has continued into November. It generally feels really cold, colder than normal. I must admit that the chilly, dark mornings do not make leaving the house and going to work conducive to productive activities! I am hoping that it’ll return to normal Winter weather soon.

Thanks to the weather, journeys in my provincial city are taking a little longer, but in London the weather has heralded the return of the infamous London fogs that make travel near impossible.

Music-wise, things have taken an interesting turn. Since I last spoke to you, the BBC have banned Bobby Boris Pickett’s The Monster Mash, from UK radio on the grounds that the song was "too morbid."

By contrast, currently at the top of the charts is Frank Ifield and Lovesick Blues. A cover of the Hank Williams classic show tune, it is not really to my personal taste, I’m afraid. Telstar, much more favourable to my ears, and the instrumental that dominated the charts over the Summer, is still in the Top 5, slowly declining (like the satellite itself).

On the television I’m still enjoying the antics of John Steed and Cathy Gale in The Avengers on ITV. Undoubtedly rather far-fetched, it is nevertheless entertainingly escapist.

Slightly more down to earth, we recently had a programme begin on the BBC that I think will run for a while. Called That Was the Week that Was, it is a satirical summary of topical political and cultural items of interest from the previous week before transmission. Presented by up-and-coming media star Mr David Frost, but also with a host of comedians to fill out the roster, it seems to have been popular ratings-wise, although admittedly less so with the politicians and the Establishment.

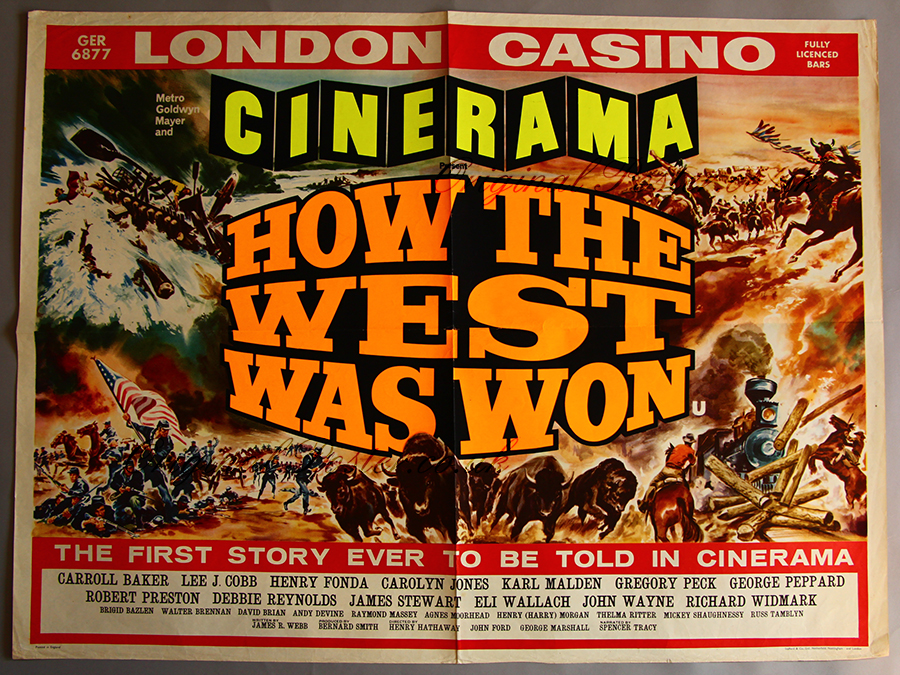

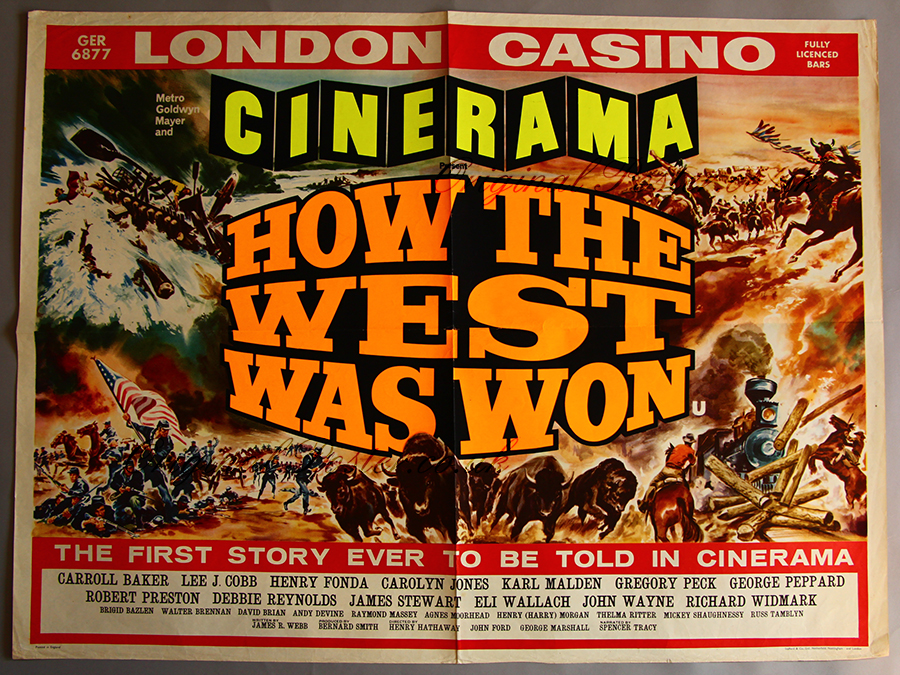

I have braved the Winter weather to go to the cinema since we last spoke – it is often warmer there! – and I must recommend How the West Was Won, which I saw a couple of weeks ago. Directed by Mr John Ford and with a great cast – Mr. John Wayne, Mr. Gregory Peck and one of my own favourites, Mr. James Stewart – it is a great epic, telling us of the early days of the Wild West. Visually spectacular in Cinerama and in stereophonic sound, this may be the standard that future movies must reach.

Hopefully as good, I am looking forward to going to see Mr. David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia before I speak to you next. The news is saying that it is a visual spectacle, if a little long at nearly four hours. As it is mainly set in the desert, though, it might just be what’s needed to keep the Winter chill out!

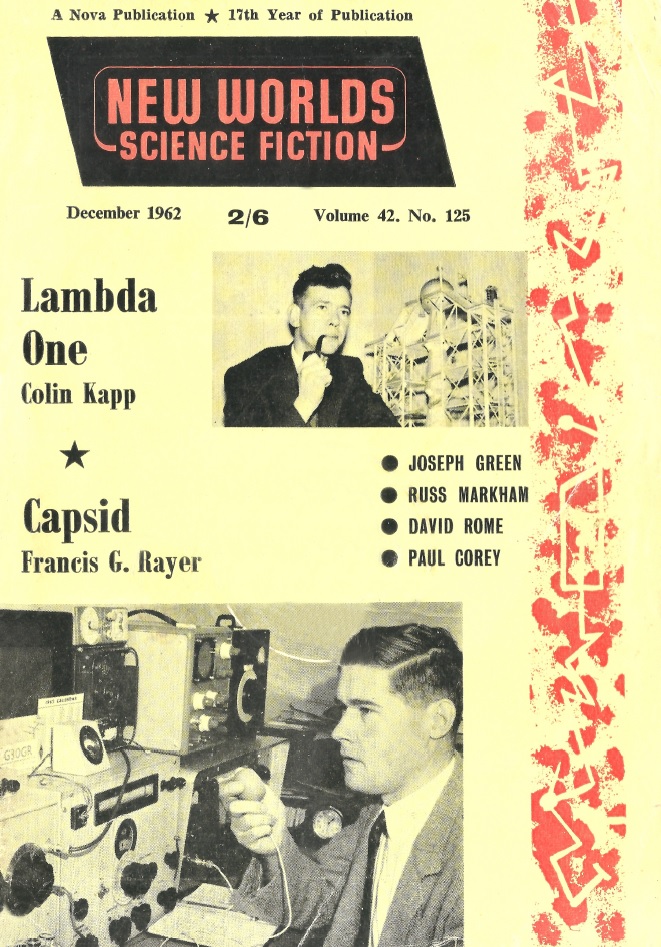

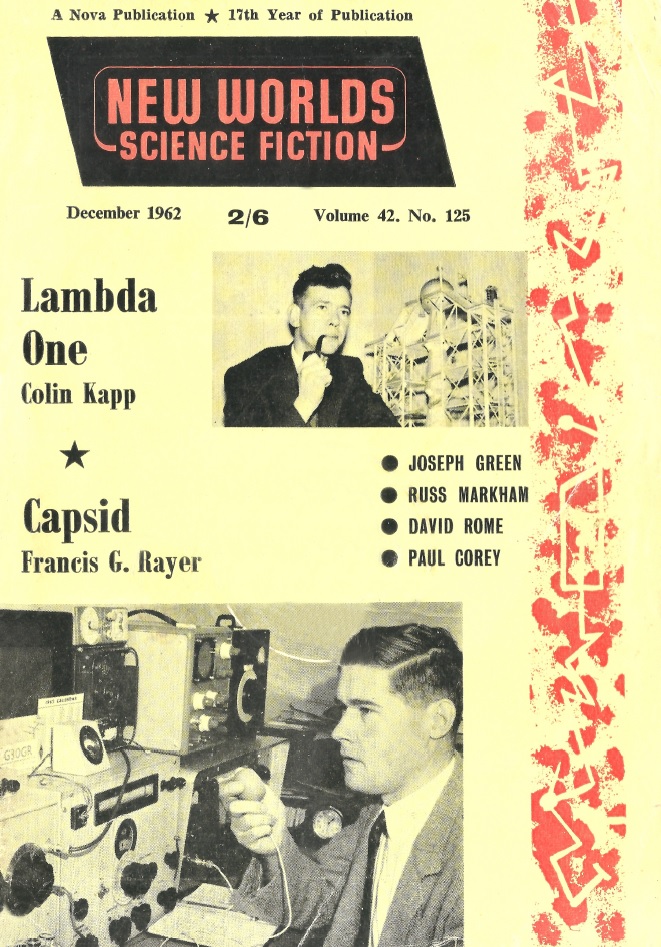

This month’s New Worlds (the 125th!) has a slightly less lurid cover (thank goodness!) and after the excitement and disappointment of last month’s issue edited by Arthur C Clarke, we are back to a more ‘business as usual’ edition this time around.

This month’s editor is a popular writer who, nevertheless, hasn’t been in New Worlds for a while. Mr. Lan Wright was last in the magazine in 1958-59 with his three-part story A Man Called Destiny (issues 78-80, December 1958, January & February 1959). This time, as guest editor, he seems to have created a rather mixed bag, but a better edition than the one previous. His writing absence is partly explained in the Profile given on the inside cover. Amongst other things he has been spending his leisure time as a radio commentator for Watford Football Club and the three associated Hospital Radio stations in the area.

This has left little time for writing, though he has managed an Editorial this month and has a new three-part serial starting next month. His Editorial reflects his clearly passionate views on s-f. In a determinedly anti-intellectual stance, Lan makes the point that the genre is better off when it is mindful of its origins and keeps things unprofessional. This is a counterview to that of John Baxter’s in September which argued that, in order to survive, s-f needs to push itself and reach out to the mainstream masses by presenting a more refined, more challenging and better written body of work.

So, it seems like the battle-lines are drawn. I suspect that this battle between the two views will continue for a while yet.

To the actual content. Two novellas this month!

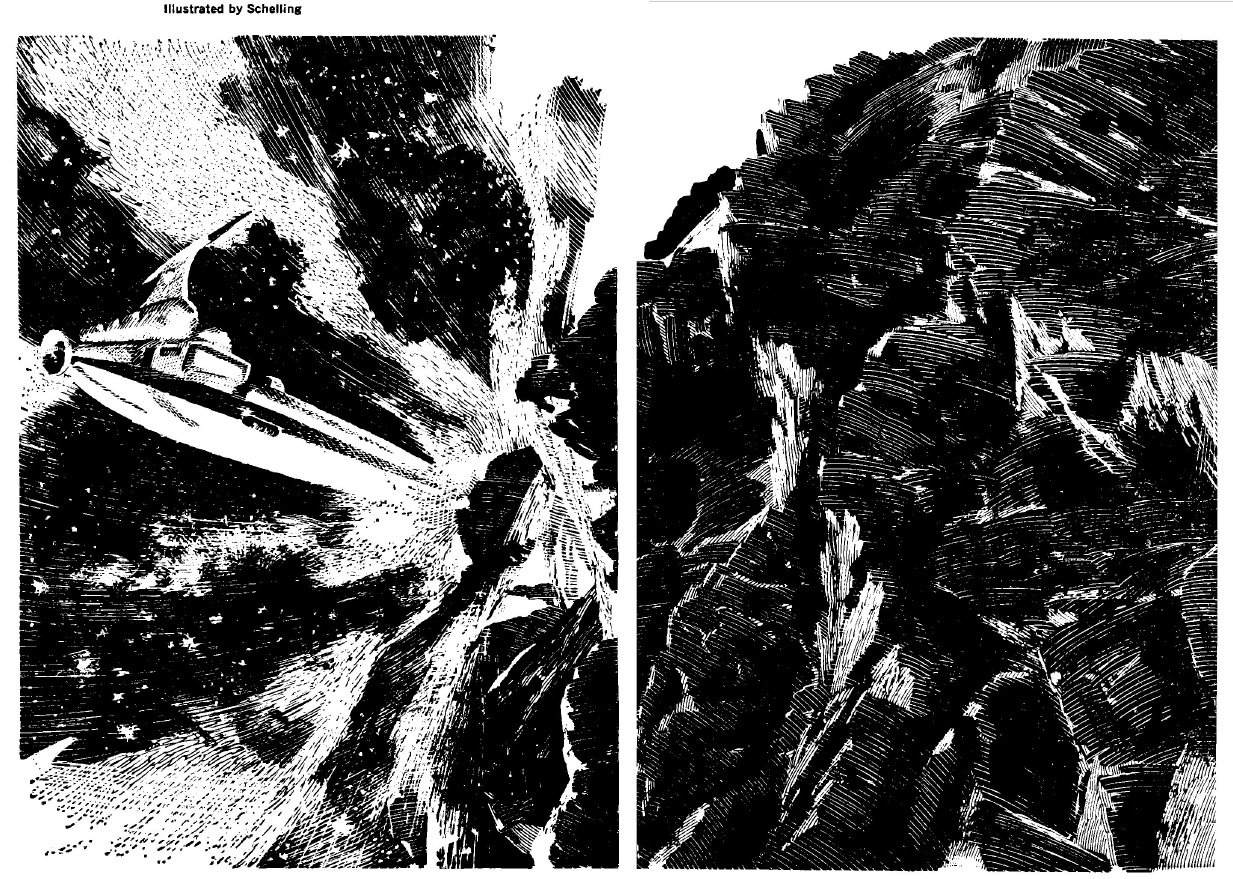

Lambda One, by Mr Colin Kapp

Mr Kapp is a New Worlds regular (last seen October 1961) and this is one of the better novellas I have read recently. The story centres around a great concept – that future transport is made by travel via an inter-atomic method. By making a solid body resonate in such a way that its atoms can pass through the spaces in the atomic structure of other solid substances, goods, materiel and people travel quickly and freely. The story follows a spaceship lost in this other dimension as our two heroes, Brevis and Porter attempt to rescue them. To be honest, the plot isn’t great and the ending is resolved far too quickly, but the journey to reach the stranded vessel is what makes the story memorable. It is, in the end, terrific fun and quite imaginative. Four out of five.

Meaning, by Mr. David Rome

This one, which I liked nearly as much as Lambda One, comes from an author who has now appeared in three issues in a row. Meaning is perhaps his best of the three. It tells of Alan Ross on a journey to Mars that may or may not be what the traveller thinks it is. This one kept me guessing by mixing dreams with reality until the mystery of the plot was revealed. Three out of five.

Capsid, by Mr. Francis G. Rayer

I really liked this story, from an author who has had stories published in New Worlds since 1947. There isn’t much to the plot (another rescue story!), but the titular alien of the story is interesting and unusual enough to be memorable. Though nameless, the "capsid" is a creature that lives underground away from the harsh radiation of its planet. It burrows through the sand and absorbs anything unlucky enough to land on the planet’s surface. When Wallsey crashes onto the capsid’s planet, the difficulty is how to rescue him from a planet where nothing seems to survive. The alien is memorable, although the ending is rather predictable. Nevertheless, three out of five.

Operation Survival, by Mr. Paul Corey

Oh dear. I’m always very mindful that humour’s always a relative thing, and what some find amusing, others don’t. Even so, this one’s a major misstep. The ‘humour’ derives from the idea that if you put enough mentally ill people (here called ‘Feebs’) in a room full of buttons, then like the proverbial monkeys writing Shakespeare, they will press the right buttons to deliver nuclear missiles, essentially lunatics taking over the asylum. Distasteful, badly judged and really, really not funny. Zero points.

Transmitter Problem, by Mr. Joseph Green

Mr. Green returns to the setting previously read in last month’s issue (the planet named Refuge.) It’s another story about the breshwahr tree, a salient lifeform, and its effect upon the people of this frontier planet. I was rather dismissive of last month’s effort, saying that its purpose was clearly designed to shock with its matter-of-fact depiction of child rape and cannibalism. I enjoyed this one more, mainly because I felt it was trying less hard to make its point. It is a minor story about transmitting people but seems to set things up for other stories in the future quite nicely. Three out of five.

Mood Indigo, by Mr. Russ Markham

The second of our novellas this month, from another author we read in the last issue. Mr. Markham's last effort was Who Went Where?, which I thought was ‘solid yet undemanding.’ This is longer, and better for it, I think. Here, engineers Don Channing, Harry Scanlon and their work colleagues create a forcefield bubble that is quickly sponsored by the military, but there are unexpected consequences of its use. It suggested what it must have been like with the development of the atomic bomb, and I rather suspect that that was the intention. It is a traditional tale, with lots of stereotypes – bold male scientist, good-looking girl, etc., although it comes out as passable s-f in the end. Three out of five.

Lastly, there’s the usual Book Review by Mr. Leslie Flood. Mr. John Christopher’s The World in Winter and Mr. Daniel F Galouye’s Dark Universe both get positive comments.

In summary, I enjoyed this issue more than last month. Whilst there are moments of workmanlike prose and a real misstep in one of the worst stories I’ve read in New Worlds, ever, there were enough original moments to make me feel that my two-and-sixpence was well spent this month.

Until next time, as I huddle under a few blankets, it just remains for me to wish you all a Merry Christmas. Have a great one, may you get everything you wish and I’ll speak to you again before the New Year.