by Mark Yon

Last month I decided I would try and NOT mention the English weather in future transmissions. But I’m a Brit, and it’s become a tradition! So, suffice it to say that the commute to work has been easier this month and, since we last spoke, the weather has been more typically Spring.

As the weather has improved, so has my mood. Another cause for cheer has been the radios being full of Britain’s latest pop sensation, The Beatles. Some of our other Travellers have mentioned their continuous rise. Their third single, From Me to You is something we can’t really avoid.

Thankfully, I do like it a lot. It’s got a great beat and terrific harmonies. I can only see these boys from Liverpool continue to dominate the charts here if they keep this up.

Mind you, the cinema also seems to be determined to dispel the bleak Winter. Britain’s answer to Mr. Elvis Presley, Mr. Cliff Richard, has recently been filling our cinemas with a cheerily bright and colourful musical, Summer Holiday!

It’s very popular and might just chase those Winter Blues away. We may not be quite there yet, but at least we can see that brighter times are ahead, even when the news is somewhat bleaker. The newspapers here are full of stories about marches against nuclear weapons, which seem to be growing year on year:

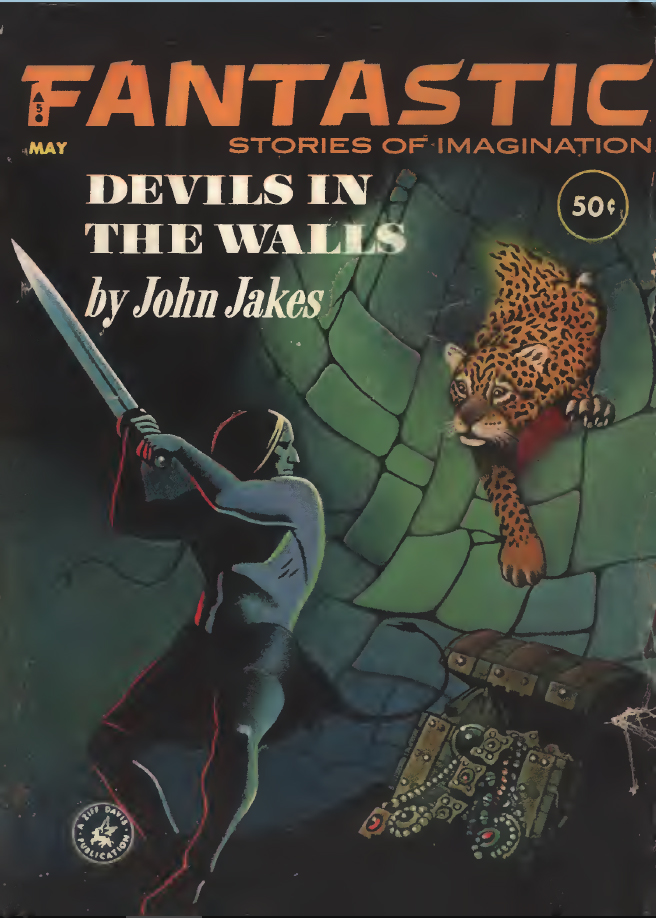

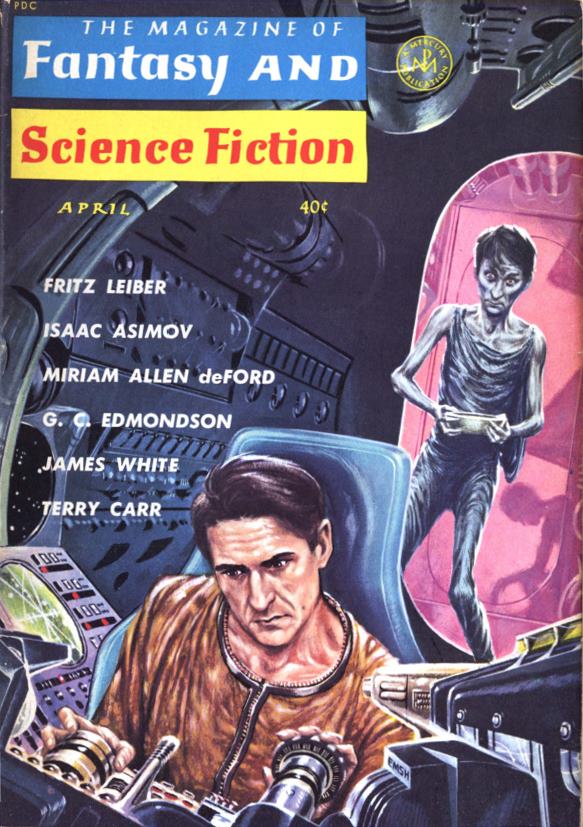

Can you see a problem with that cover? No, not the bright daffodil-yellow colour, nor the lack of author photographs, although that is disappointing. Look at the title of the Mr. Aldiss novella. See it? Such mis-spellings are shoddy and frankly embarrassing. A big minus mark for Mr. John Carnell this month. Does he really care about this magazine? It’s a shame, because there’s a lot to like in this issue. There’s even a common theme, as many of the stories this month seem to look at the conflict between order and chaos, between discipline and dissent. This also applies to the Editorial!

From The Edge of the Pond, by Mr. Lee Markham

Australian Mr. Markham has been a regular contributor to the stories of late and here in the capacity of Guest Editor he brings a forthright summary of the ongoing debate on the state of s-f. He doesn’t mince words, though.

“I don’t think any of us were surprised when some of the opinions expressed turned out to be, in turn, introspective, belligerent, and, in the case of John Rackham and Brian Aldiss, personally prejudiced and blandly indifferent.”

Well, I guess that’s telling us! For all that, it’s an interesting summary to this (still) ongoing discussion, made impressive by the sheer number of other authors and works used to argue its case.

Speaking of Mr. Aldiss, it is his novella (with the mis-spelling!) that holds prime position on the cover this month, albeit back at the rear of the magazine again. More later…

To the other stories.

Confession, by Mr. John Rackham

Like last month’s story from Mr. Rackham, another tale of ‘supermen,’ here called an ‘X-person,’ which even the story banner admits has “slan-like” similarities. Despite this unoriginal concept, Confession was more enjoyable than last month’s effort. It’s set on a nicely imagined thixotropic (ketchupy) world, but really examines the tension created between discipline and intelligence when in a military situation, which was nicely done. Three out of five.

The Under-Privileged, by Mr. Brian W. Aldiss

The return of Mr. Aldiss to New Worlds is a welcome one, especially after his recent success with his Hothouse series in the United States. Mr. Aldiss himself celebrates this return with his usual sense of humour in an inside-cover Profile:

The Under-Privileged is a fine story of immigration and alien resettlement which, under its positive tone, left me with a certain degree of unease, as I suspect is its goal. As ever from Mr. Aldiss, it is a story of social s-f rather than the traditional, but the style and the underlying nuances of the plot suggest a superior piece of work. It’s not Hothouse, but I enjoyed it. Four out of five.

The Jaywalkers, by Mr. Russ Markham

Mr. Markham’s tale is another reasonable effort in the Galactic Union Survey stories, this time on a planet which is not what it seems. It’s based around a nice idea, but it almost drowns in its scientific gobbledegook explanation towards the end. Three out of five points.

I, the Judge, by Mr. R. W. Mackelworth

I really liked Mr. Mackelworth’s debut in New Worlds in January, but this one is even better. I, the Judge is a story of future law and order, in a style very different from his first story. Shocking and revelatory, I, the Judge, in terms of its literary style and its complexity of concept, dazzled. I felt that it even put Mr. Aldiss’s effort in the shade. Rather made me think of the stories of Mr. Harlan Ellison, and echoes this month’s running theme of discipline and disorder , by highlighting the value of defiance against obedience. This may be the future of s-f. It is one of the most memorable plots I’ve read in recent months. Four out of five, my favourite story of the issue.

Window On The Moon, by Mr. E. C. Tubb

The second part of this serial moves things on-apace, as it should. Our hero, Felix Larsen, tries to get to the bottom of things, whilst others pick up a mysterious means of communication leaked from the British base, which leads to a visit from the Americans. There’s a rather unpleasant parochial part about how the Brits ‘see’ Americans and vice versa, but that aside, it was surprisingly exciting, to the point where I’m going to increase last month’s score from three-out-of-five to four this month. Really looking forward to the conclusion next time.

At the back of the issue there is the return of the Postmortem letters section, although there is only one, admittedly lengthy, letter, where Mr. John Baxter eviscerates Mr. Lan Wright for his Editorial in the December 1962 issue. It makes entertaining reading, if rather painful.

There’s also another The Book Review this month from Mr. John Carnell. There’s reviews of the “interesting revival” of Mr. Robert Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky, Mr. William Tenn’s Time in Advance and the “thoroughly enjoyable, non-cerebral” entertainment of Mr. Mark Clifton’s “wonderfully witty” When They Come from Space. Mr. Eric Frank Russell’s collection of his early work, Dark Tides is rather less polished than his latest efforts, but still recommended.

In summary, the erroneous cover belies an issue that is much better than that typo would suggest. Whilst some stories seem to be marking time, some are great, making this one of the strongest issues I’ve reviewed so far. The future may be bright. However, I am beginning to question Mr. Carnell’s editorship, particularly after the efforts of Mr. Moorcock last month. I am starting to feel that his attention is elsewhere or, just as bad, that he is rather too stretched to focus on producing a quality magazine. This is a concern.