by Gideon Marcus

How quickly the futuristic becomes commonplace. Just two years ago, I marveled about how fast one can cross the oceans by jet. Now, on the eve of another trip to Japan (we really have joined the Jet Set, haven't we?) I look at the flight itinerary and grumble. Why must we stop in Hawaii? That adds several hours to the trip — it'll take more than half a day to get from LAX to Haneda.

Spoiled rotten, I tell you.

Speaking of travel stories, a fresh crop of science fiction digests has hit my mailbox. Many of them will be joining me on my trip to the Orient, but I finished one of them, the July 1963 IF, pre-flight. All of them feature some element of star-hopping, and so this issue sets a fine mood as we embark on our latest journey:

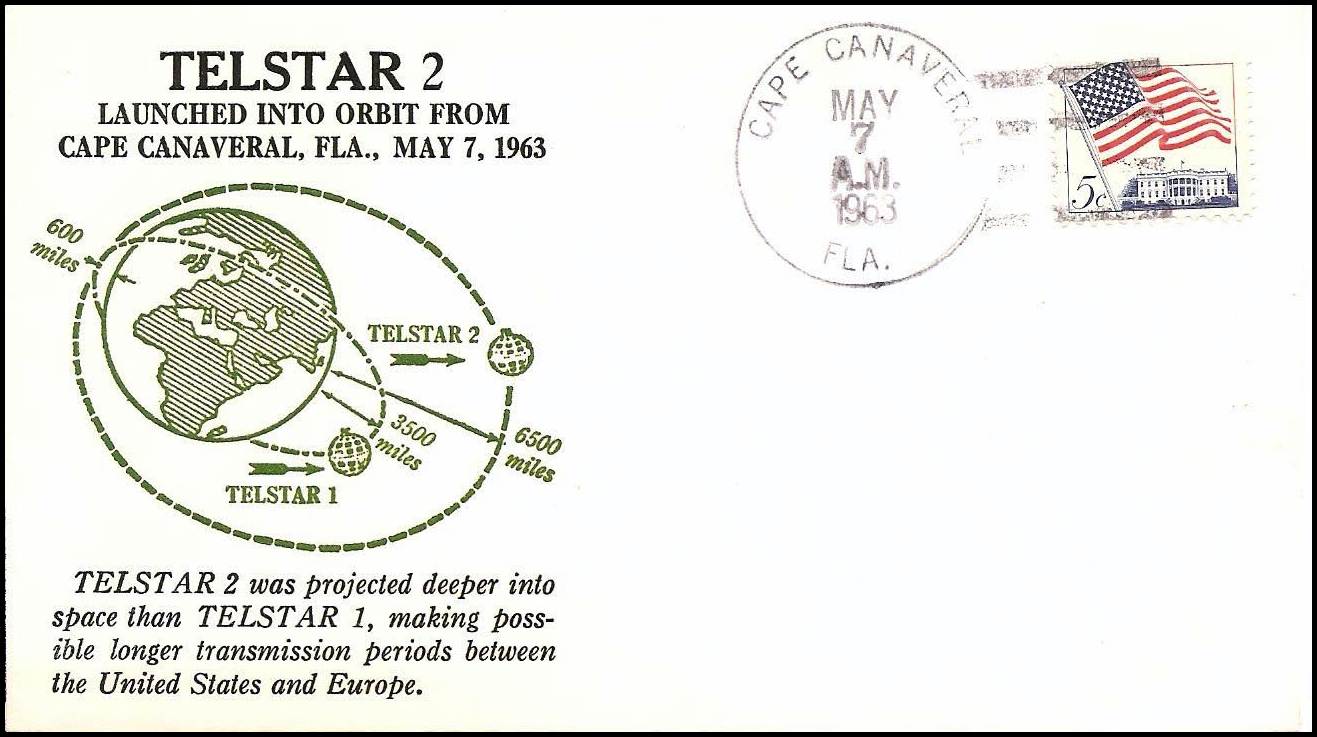

That Notebook Again, by Theodore Sturgeon

I find it interesting that editor Fred Pohl has gotten Ted Sturgeon to write his editorials for him. I'm not complaining — it's always nice to see Sturgeon in print in any capacity. This time around, he treats us to a number of technological proposals, a wishlist of inventions that should be right around the corner, given a little interest and effort. I found his idea for a home TV-tape camera and player particularly titilating (and not farfetched — my nephew already audio-tapes television shows onto reel-to-reel).

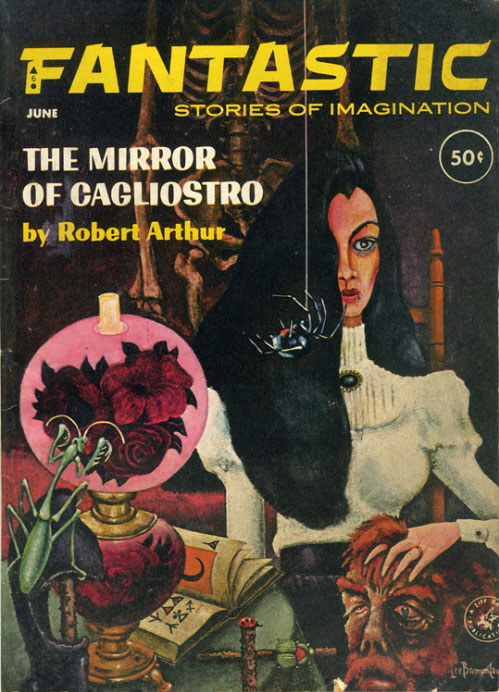

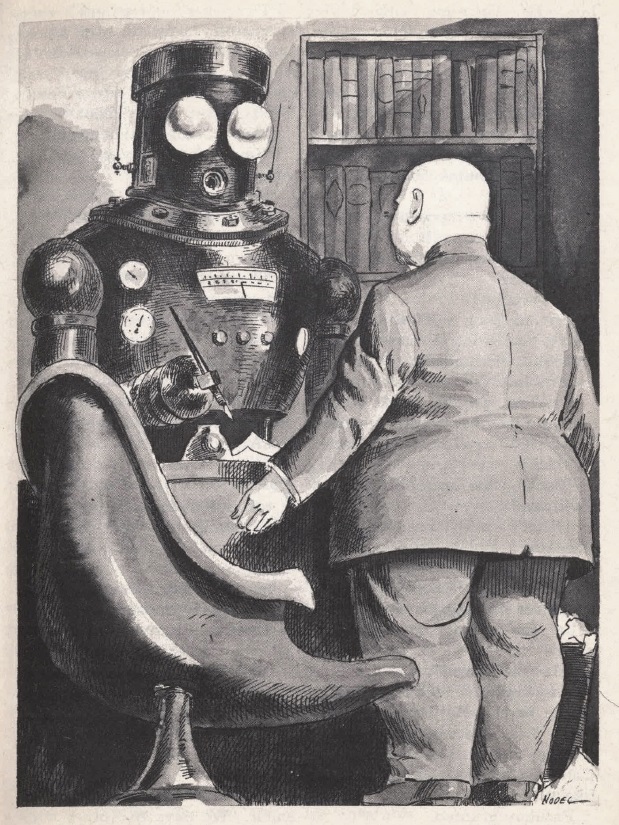

The Reefs of Space (Part 1 of 3), by Jack Williamson and Frederik Pohl

A good third of the issue is given to a new serial (illustrated on the cover — EMSH is big in this issue, though I also like the work of Nodel, who is new to me). Hundreds of years from now, Earth's population is highly regimented, its economy utterly socialized, under the authority of The Machine and its master Plan. Dissent is punished by incarceration and the forced wearing of an explosive ring around one's neck. Further disobedience results in one's "salvage" (dissasembly into component body parts for the use of others).

Steve Ryeland is an experimental physicist, a touchy job to have when scientific advancement poses both boon and risk for the Plan. At Reef's beginning, he has been a prisoner for three years, unaware of his crime, but consistently questioned about "spacelings," "fusorians," "reefs of space," and "jetless drive" — terms about which he knows nothing. Adding to his confusion is a three-day gap in his memory.

And then comes the urgent summons — the Machine will have Ryeland discover the secret of the reactionless drive, and soon, or be sent to the Body Banks. For at the edge of the solar system lies a biological construct, the tremendous analog of a coral reef created by organisms that live on interstellar hydrogen. Not only does this alien structure pose a hypothetical threat to the Plan, but it affords sanctuary to a more existential opponent — the revolutionary-in-exile, Donderevo. Can Ryeland accomplish his mission in time to save his hide and human society? Is such a goal even worth fighting for?

It's an interesting concept for a novel, but the execution leaves a bit to be desired. It suffers from the same plodding repetitiveness as Simak's concurrent serial in Galaxy, but betrays none of Simak's literary expertise. The writing is simple, uninspired, and the scientific concepts (including Hoyle's steady-state theory, which I find uncompelling) feel dated. Two stars, but with cautious hopes for the next installment.

The Faces Outside, by Bruce McAllister

Here is a short tale of a married couple, the last of humanity, mutated to live in a large alien aquarium with a host of other terrestrial life forms. The Terrans have the last laugh when the male of the pair develops psychic powers and compels the aliens to commit mass suicide.

McAllister is the first and weaker of the two new authors featured in this issue. His writing shows potential, though. Two stars, trying hard for three.

Mightiest Qorn, by Keith Laumer

Another IF, another Retief story. This time, the omnipotent but much-suffering Terran agent is tapped to investigate the sudden reappearance of the fearsome Qorn, a race of dreadnought-wielding, glory-seeking warriors who appear to have the power of teleportation.

Unfortunately, the Retief shtick is starting to wear thin (arguably, it raveled a while ago), and it's really time Laumer focused his attention to the more worthy efforts we know he's capable of. The bright spot is that Retief's nominal boss, Magnan, is now pretty game to do whatever his "underling" says. Some might call that progress. Two stars.

In the Arena, by Brian W. Aldiss

Given up? Take heart — it's all better from here. Prominent British writer, Aldiss, gives us another man-and-woman pair in the thrall of aliens. In this case, it is two gladiators performing for a race of insectoids who have conquered the Earth (but not all of humanity). Call it Spartacus for the 30th Century. It's a nicely written trifle. Three stars.

Down to the Worlds of Men, by Alexei Panshin

14-year old Mia Havero is part of a society of human space-dwellers, resident of one of the eight galaxy-trotting Ships that represent the remains of Earth's high technology. She and 29 other young teens are dropped on a primitive colony as part of a rite of passage. There is always an element of danger to this month-long ordeal, but this episode has a new wrinkle: the planet's people are fully aware (and resentful) of the Ships, and they plan to fight back. Can Mia survive her coming of age and stop an insurrection?

Panshin hits it right out of the park with his first story, capturing the voice of a young almost-woman and laying out a rich world and an exciting adventure. Finally, I've got something I can recommend to the Young Traveler. Four stars, verging on five.

The Shadow of Wings, by Robert Silverberg

The last story introduces Caldwell, an expert in the dead language of Kethlani. He is called back from a family vacation when a real live Kethlan shows up, bearing the banner of peace. Can the linguist overcome his revulsion of the alien's form and forge a partnership between the two species?

This piece could have been a throwaway save for Silvergerg's careful drawing of the Caldwell's personality. I found myself wishing the story had been longer — certainly, it could have taken some of the pages away from the stale stories of the first half. Four stars.

Like my impending vacation, this month's issue starts with a hard slog but ends with great reward. I'd say that's the right order of things. See you in Tokyo!