by Victoria Silverwolf

The Past is Prologue

The closing of two amusement parks in recent days caused many to look back nostalgically on the innocent fun of yesteryear.

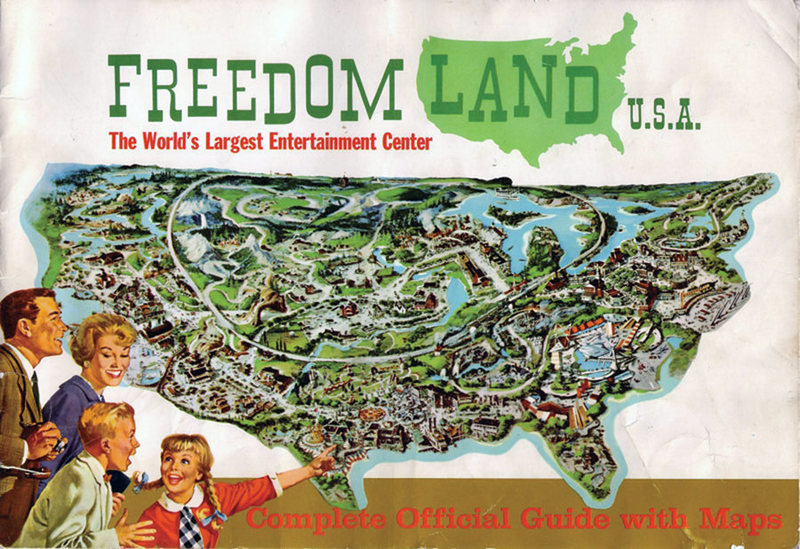

Freedomland U.S.A., only four years old, shut its doors for good this month. Located in the Bronx, this Disneyland-with-a-New-York-accent featured several theme areas, including fun-filled, if not very accurate, recreations of the past and the future.

The world's largest, but not the most successful.

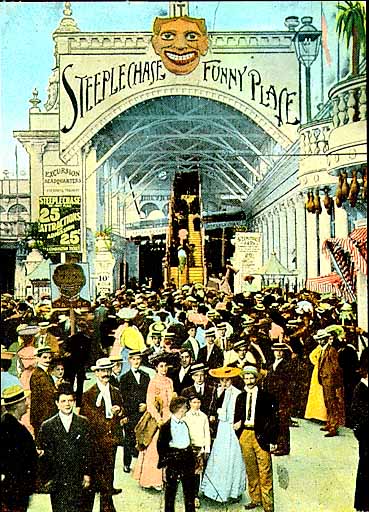

Only a few days later, the Coney Island attraction Steeplechase Park, which opened way back in 1897, received its last visitors as well.

Were you there six decades ago?

Popular music also turned to the past, as a new version of the folk song The House of the Rising Sun by the British rockers The Animals reached the top of the American charts early this month. It is still Number One as I type these words.

That's really lousy cover art for such a great song.

It's not unusual for a remake of an old number to become a hit, but this is an extreme example. Musicologists tell us the song's origins may go back as far as Sixteenth Century England, although this is a matter of debate. In any case, I was stunned, in a pleasant way, when I first heard this version. Eric Burdon's powerful vocals and Alan Price's compelling electronic organ solo make this a new classic, if you'll pardon the oxymoron.

In a similar way, the two longest stories in the latest issue of Fantastic seem to have come out of the yellowing pages of an old pulp magazine.

Gimme That Old-Time Sci-Fi, It's Good Enough For Me

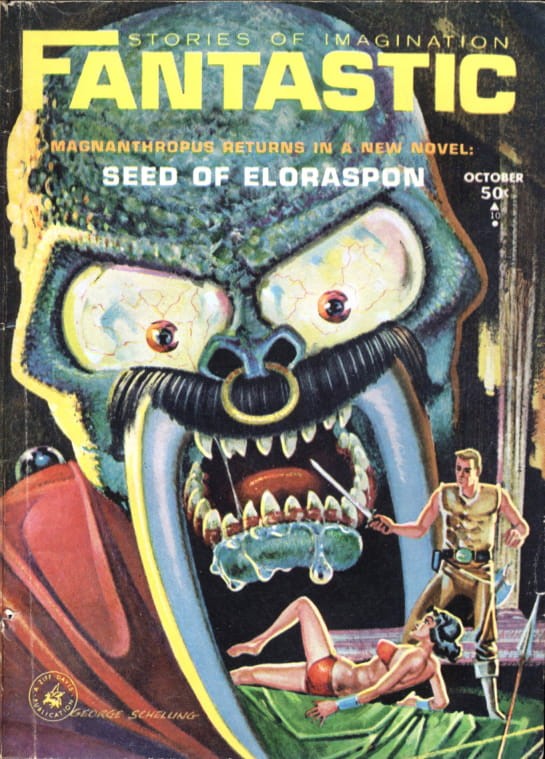

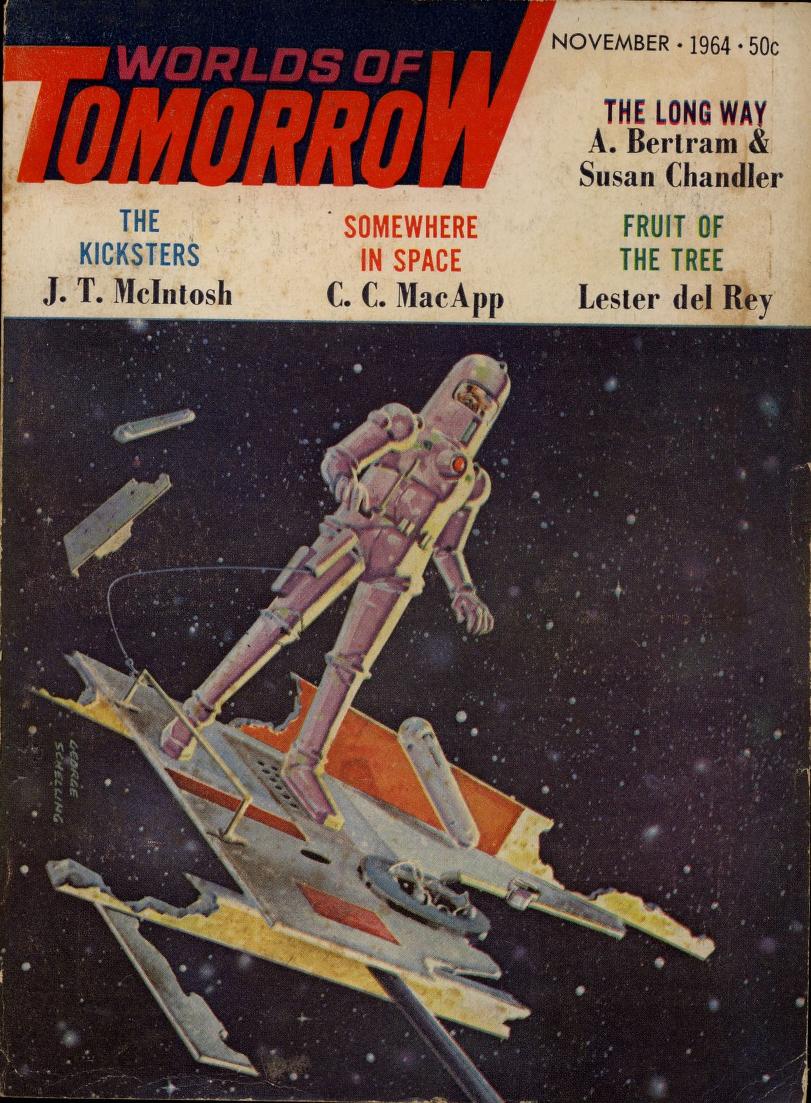

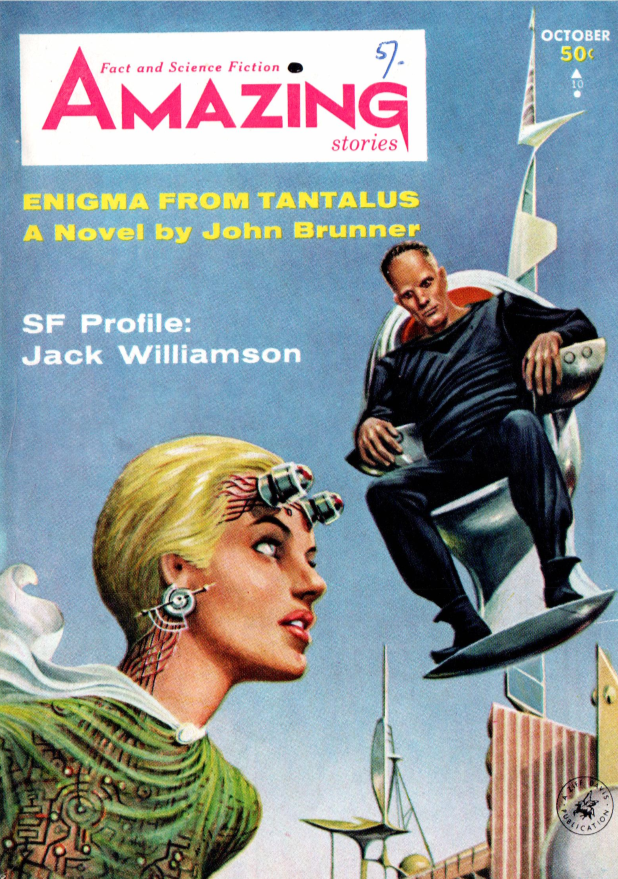

Cover art by George Schelling

Beyond the Ebon Wall, by C. C. MacApp

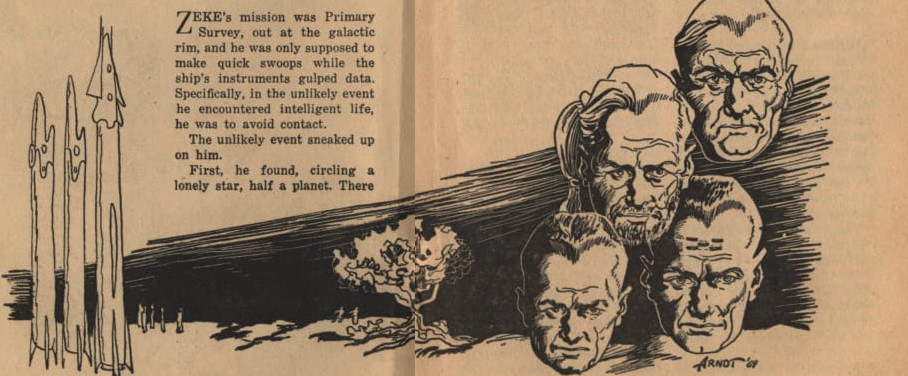

Illustrations by Michael Arndt

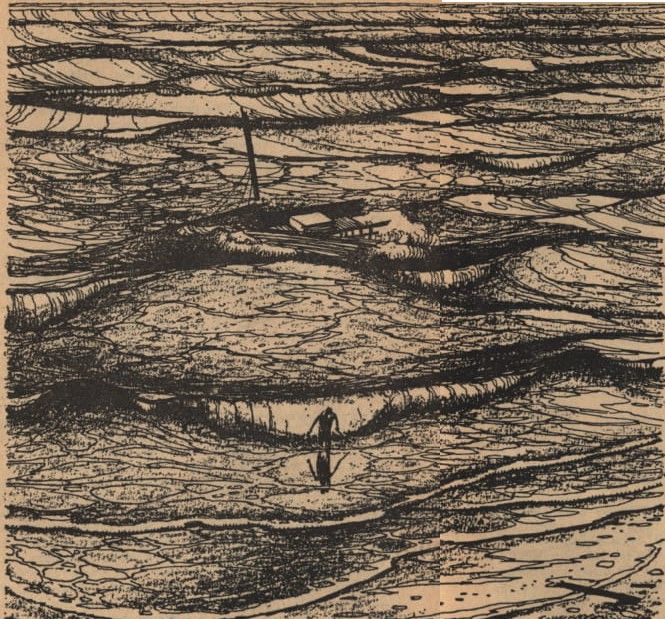

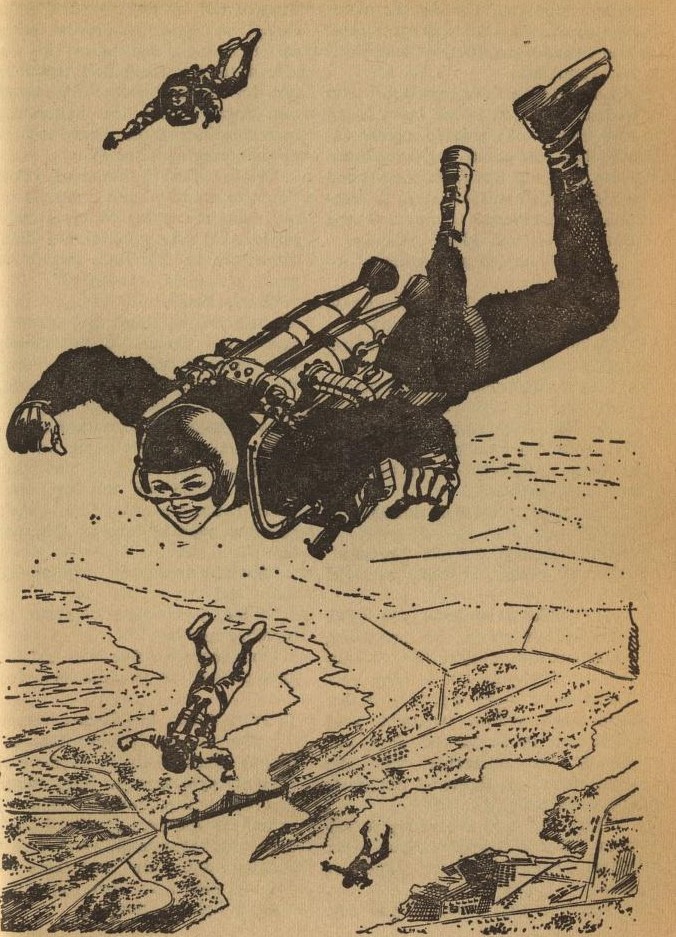

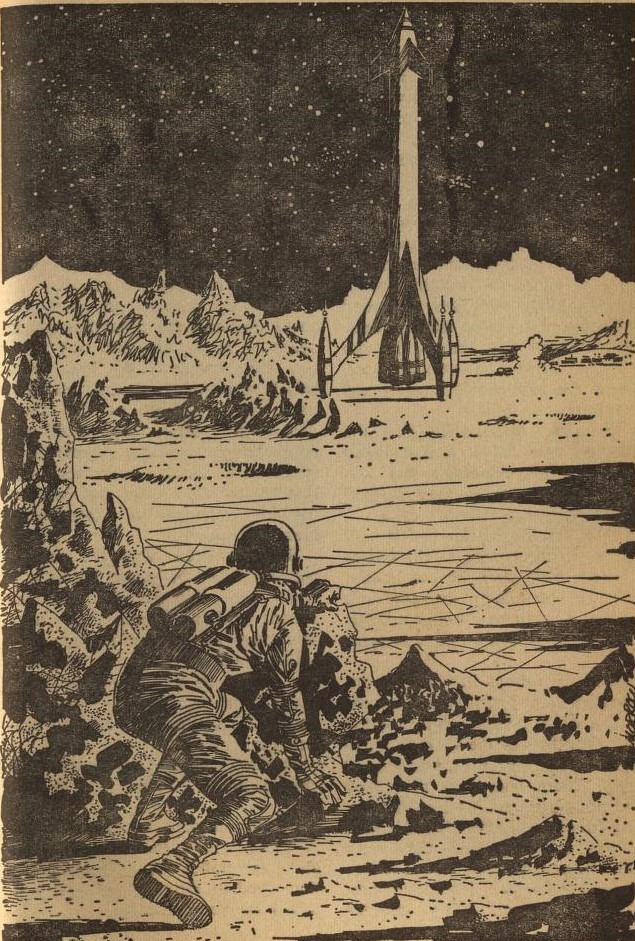

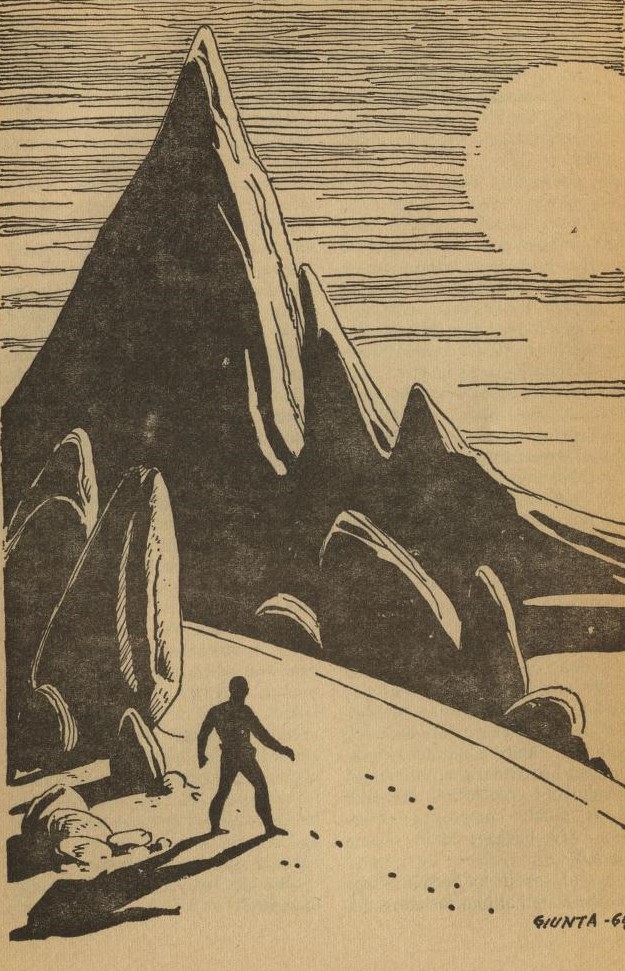

This yarn starts off with the hero making a routine survey of a distant solar system. He finds a bizarre planet, half of which is missing, cut away from the other half by a black wall. Don't expect a hard SF story in the tradition of Hal Clement, with a scientific explanation for the weird phenomenon. Once the guy lands on the planet, the story becomes pure fantasy, of the sword-and-sorcery kind.

He meets four men, one of whom is an elderly fellow with a scarred face. There is also a pair of naked men fighting near the black wall. These two vanish into the wall, and the hero rather foolishly follows them. He finds himself trapped in another world, where he encounters another scarred old man, who seems to be the twin of the first one. We also get our first strong clue that we're not in Kansas anymore, Toto, when a magpie recites a prophetic poem to him.

What follows is an adventure story, full of action, and yet somehow leisurely. The hero is captured, and becomes the slave of a seafaring merchant who treats him decently. He becomes good buddies with a huge guy, who serves as our source of exposition. The two of them act as bait during the hunt for a dangerous animal. Surprisingly, the creature becomes as loyal to him as a friendly dog.

Does this look like a good house pet to you?

Stir in a pirate captain, a sorcerer, battles, escapes, and chase scenes. The hero eventually winds up where he started, and the story ends with a confusing time travel paradox.

The space exploration opening adds nothing to the plot, and even the time travel theme could have been the result of black magic. Other than the awkward blending of genres, this is an old-fashioned swashbuckler right out of Weird Tales. The hero and his giant pal are likable enough, but their adventures don't lead to very much.

Two stars.

The Grooves, by Jack Sharkey

Illustration by George Schelling

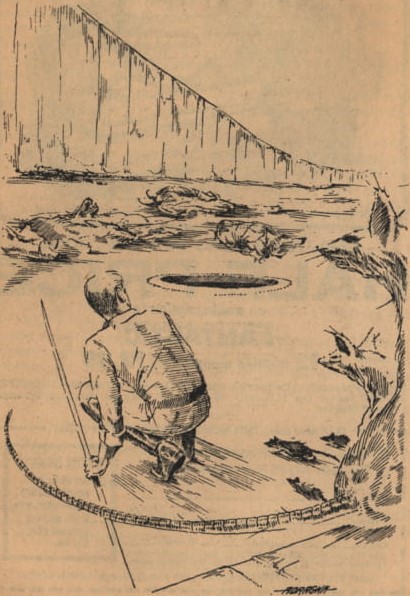

A foolhardy young man tells his grandmother that he's going to go into the underground lair of a troll and steal its gold. The old lady warns him that he must never kill a troll. We also find out that trolls have inverted souls, so they walk on the ceilings of their caverns. (No, that didn't make much sense to me, either.)

At this point, I thought that the trolls were going to turn out to be aliens, or maybe people in spacesuits. Nothing of the kind happens. The story is pure fantasy, and the plot is as simple as can be. The stupid protagonist discovers why he shouldn't kill a troll, and learns the meaning of a couple of marks on the wall of the cave, the secret of which is neither surprising nor interesting.

Two stars.

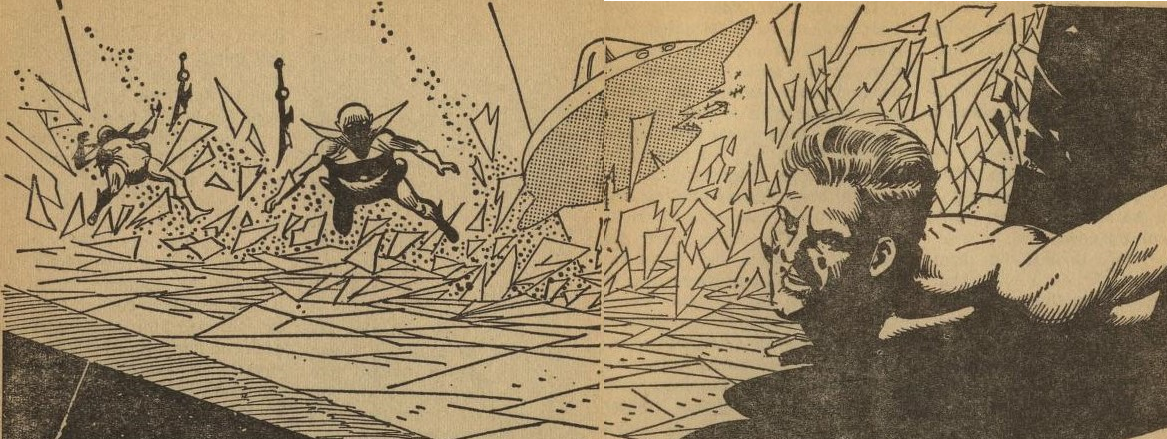

Seed of Eloraspon (Part One of Two), by Manly Banister

Illustration by George Schelling

Allow me to indulge in a little reminiscing of my own. My very first article for Galactic Journey, almost exactly three years ago, was about the October 1961 issue of Fantastic. Included in the magazine was the second half of the short novel Magnanthropus by Manly Banister. For reasons I cannot explain, this work was very popular with readers. Here comes the sequel.

In the first novel, the main character crossed over from a future Earth to the planet Eloraspon when the two worlds somehow collided with each other across dimensions. As far as he knew, Earth was destroyed. He also found out that he was a Magnanthropus, which is a kind of superman with special mental powers.

The sequel begins with the hero traveling from the northern continent of Eloraspon to the southern one, in search of the city of Surandanish, the ancient capital of an advanced civilization, now vanished. (His Magnanthropus powers direct him to seek out the place, for reasons not yet clear.) Along the way he meets the fairy-like beings we saw in the first story, although they don't have anything to do with the plot, so far.

The charming but irrelevant butterfly people.

He rescues a beautiful warrior princess from a monster and they fall in love so fast it'll make your head spin. Interfering with their romance are the Tharn, a bunch of nasty, ugly folks who live only to kill and enslave. The hero battles one Tharn who used to be a regular fellow, but who lost his good looks when he consumed some of the addictive substance that makes the Tharn so hideous and mean. (Take a look at the cover art for a portrait of a Tharn. The real thing isn't anywhere near that big, however, only a little larger than a non-Tharn.)

Defeated in battle, the Tharn-who-wasn't-always-a-Tharn becomes the hero's loyal companion. Together they set out after the princess, who was captured while they were fighting. They get thrown in a dungeon, but the hero uses his convenient Magnanthropus abilities to travel through walls and attack their captors.

Take that, Tharn scum!

He also acquires another ally, a fellow Earthman who tells him that the world wasn't really destroyed, although it was badly shook up. They meet the mysterious Bronze Men, who are supposed to be immortal, although the hero apparently kills one of them pretty quickly. Our trio of Good Guys wind up captured again, and this half of the novel ends as they are about to be slain by a flying monster, while the princess is held captive by the leader of the Tharn.

Like the lead novelette by MacApp, this is an old-fashioned fantasy adventure with some science fiction trappings. I suspect that fans of Edgar Rice Burroughs made up a good portion of those who praised the first novel, with a comment like they don't write 'em like that anymore. Frankly, I'm glad they don't.

Two stars.

Home to Zero, by David R. Bunch

Nobody will ever accuse this author of rehashing old-time stories. His latest offering is a typically opaque and depressing bit of prose, written in his usual eccentric style. As far as I can tell, it has something to do with a being who used to be a man, but is now all machine. He, or it, or possibly humanity in general, sent probes out to the ends of the cosmos. Now it, or he, seeks only nothingness. Maybe. Your guess is as good as mine. At least it's weird enough, and short enough, to avoid boredom.

Two stars.

Encounter, by Piers Anthony

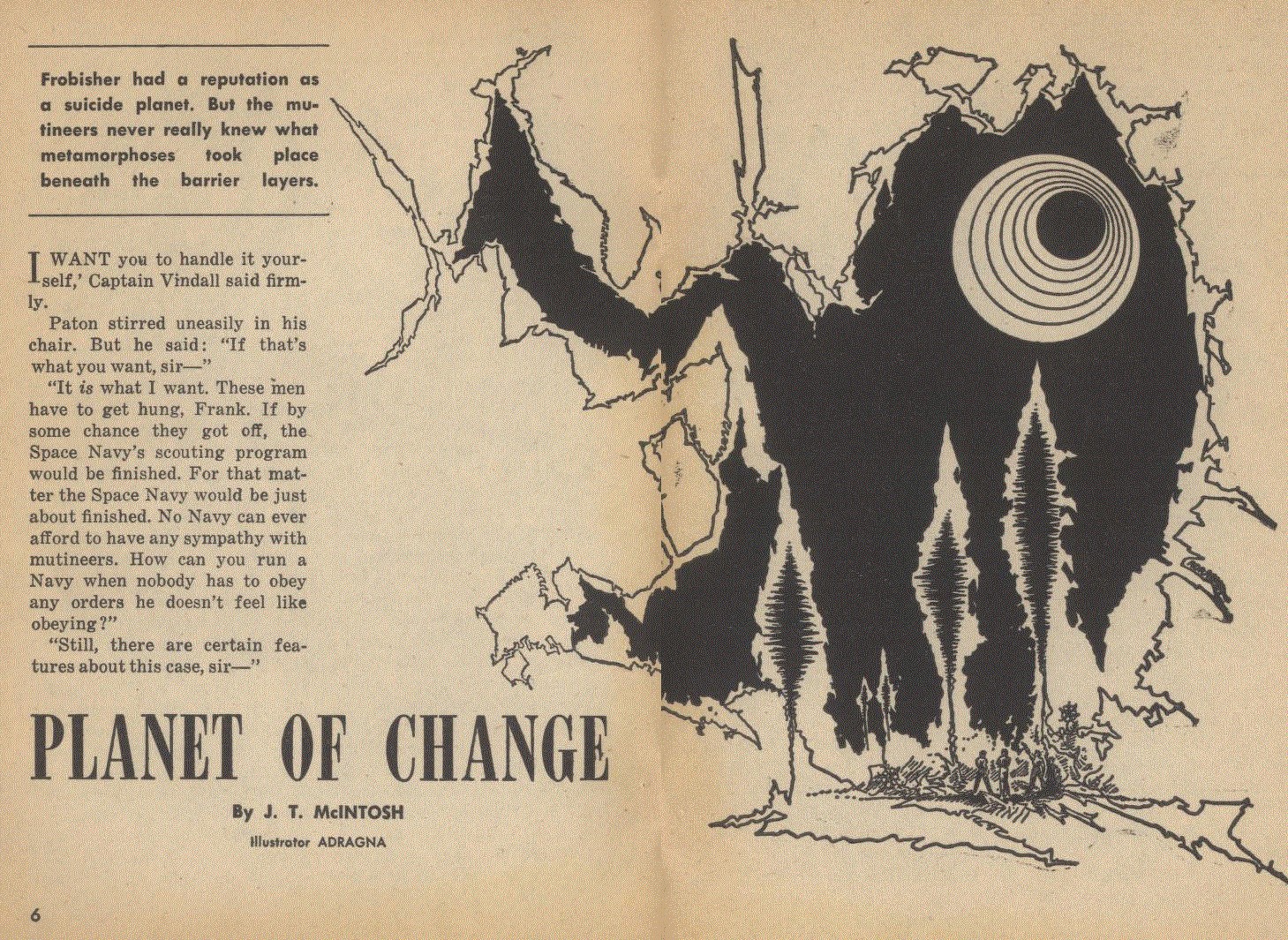

Illustration by Robert Adragna

The protagonist lives in an ultra-urbanized future, where most people never leave their homes. He travels an incredibly long road through a deserted area, inhabited by packs of feral dogs and hordes of rats. Although the setting is the Atlantic coast of North America, he also encounters savage peccaries, and, most amazingly, a tiger. The man and the cat become wary allies in their mutual battle against the wild pigs.

It was a relief to read a story that was neither corny nor incomprehensible. It's a reasonably enjoyable little tale, which achieves its modest goals in an efficient, if unspectacular, way.

Three stars.

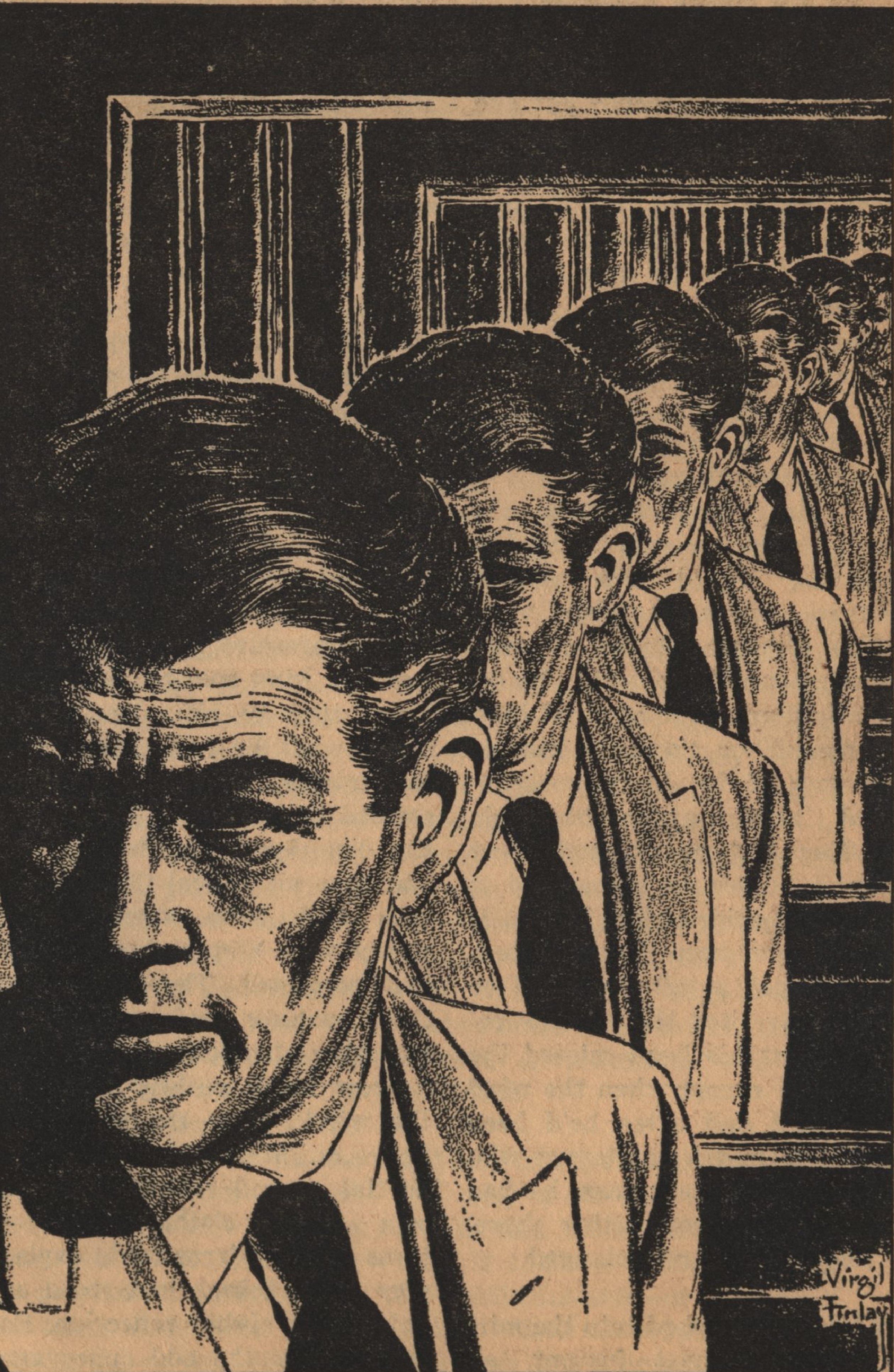

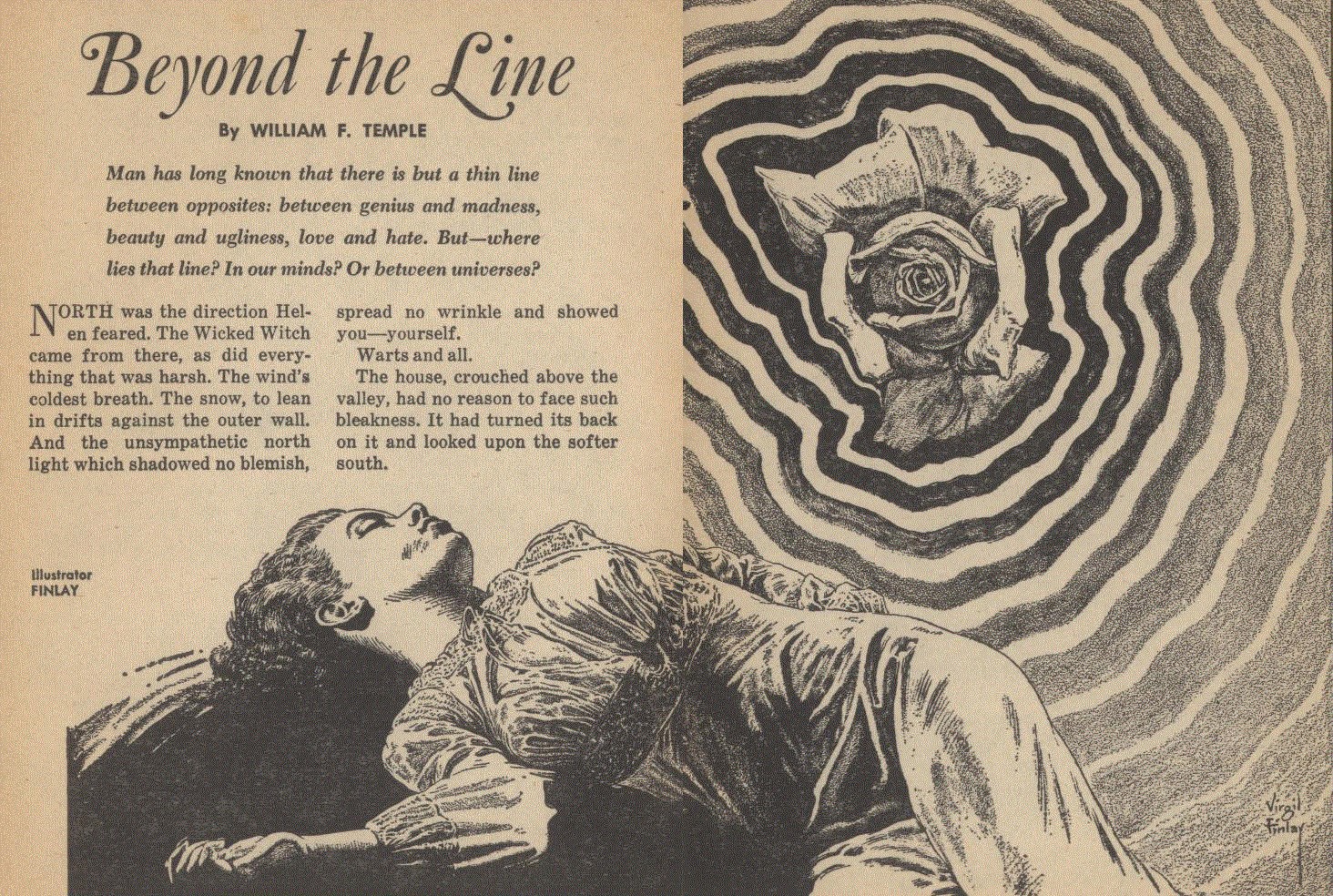

Midnight in the Mirror World, by Fritz Leiber

Illustration by Virgil Finlay

One of the easiest ways to look back at things is to gaze into a mirror. It's not a coincidence, I believe, that the word reflection can refer to an image seen in a shiny surface, or to the act of musing over one's experiences. Such were my thoughts, anyway, when I read the newest creation by a master of imaginative fiction.

The protagonist is a man in late middle age, divorced and living alone, who sleeps during the day and enjoys his three hobbies of astronomy, correspondence chess, and playing classical music on his piano at night. (Sounds like a pretty nice lifestyle to me, to tell the truth.)

As part of his nightly routine, each midnight he passes between two parallel mirrors on his way to the piano. As many of us have experienced, this creates the illusion of an infinite number of selves within the glass. One night, he sees a dark figure touching one of his reflections, which seems terrified. Each night the figure comes closer, until he recognizes it. Inevitably, the figure emerges, leading to a final encounter.

The synopsis I've provided makes this sound like a supernatural horror story, and that's certainly an accurate description. Will you believe me if I tell you that it's also a love story, and that the frightening ending can also be seen as a happy one?

Beautifully written, with the author's elegant style and gift for striking images on full display, this quietly chilling tale draws the reader into its world of darkness and light. The conclusion may not be completely unexpected, but it's a fine story nonetheless.

Four stars.

Nostalgia Ain't What It Used To Be

So how was this literary trip down memory lane? Disappointing, for the most part. I suppose it's only natural to yearn for the things one enjoyed at a much younger age, but science fiction and fantasy have progressed, I think, over the past several decades. It's no longer enough to have mighty heroes combating fiendish villains in an exotic setting.

The avant-garde writings of Bunch warn us, however, that's it's possible to go too far the other way, and throw out the baby of clarity with the bathwater of familiarity. Leiber, and to a lesser extent, Anthony, understand this, and manage to provide readers with something new, while paying the proper amount of tribute to literary traditions.

I wonder if, sometime in the Twenty-First Century, SF fans will look back at the stories of the Sixties with a wistful sigh, and crack open the brittle pages of an old magazine in an attempt to bring back the sensations that felt so new at the time.

An old science fiction classic worth revisiting.

![[September 24, 1964] Looking Backward (October 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/fantastic_196410-3-383x372.jpg)

![[September 22, 1964] Fall back! (October 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640922cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 18, 1964] Split Personality (October 1964 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640918cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 16, 1964] The Waiting Game (November 1964 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/worlds_of_tomorrow_196411-3.jpg)

![[September 12, 1964] A Mysterious Affair of Style (October 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/amz1064cover-618x372.png)

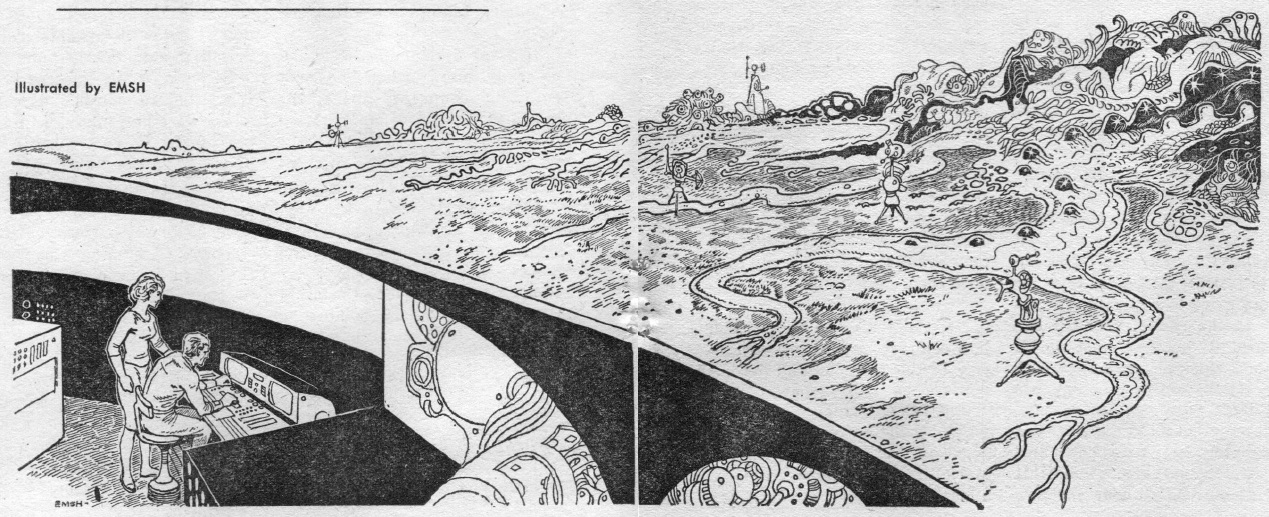

by Ed Emshwiller

by Ed Emshwiller

![[September 8, 1964] It's War! (The October 1964 <i>Galaxy</i> and the 1964 Hugos)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640908cover-672x372.jpg)

![[September 2, 1964] Taking on The Man (September 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640902cover-495x372.jpg)

![[August 27, 1964] Change..? ( <i>New Worlds</i>, September-October 1964)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640827newworlds-1-553x372.jpg)

![[August 25, 1964] Combat Zones (September 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/FANTSEP1964-e1565757244659-427x372.jpg)

![[August 21, 1964] The Good News (September 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640821cover-672x372.jpg)