Be sure to tune in tonight at 7PM Pacific for a terrific Science Fiction Theater!

by Gideon Marcus

It shouldn't happen here (or anywhere)

It was a scene out of Saigon or Prague. It shouldn't be happening in Middle America. On May 4, Ohio National Guardsmen, shot four Kent State students dead, wounding ten more. Here's what we know:

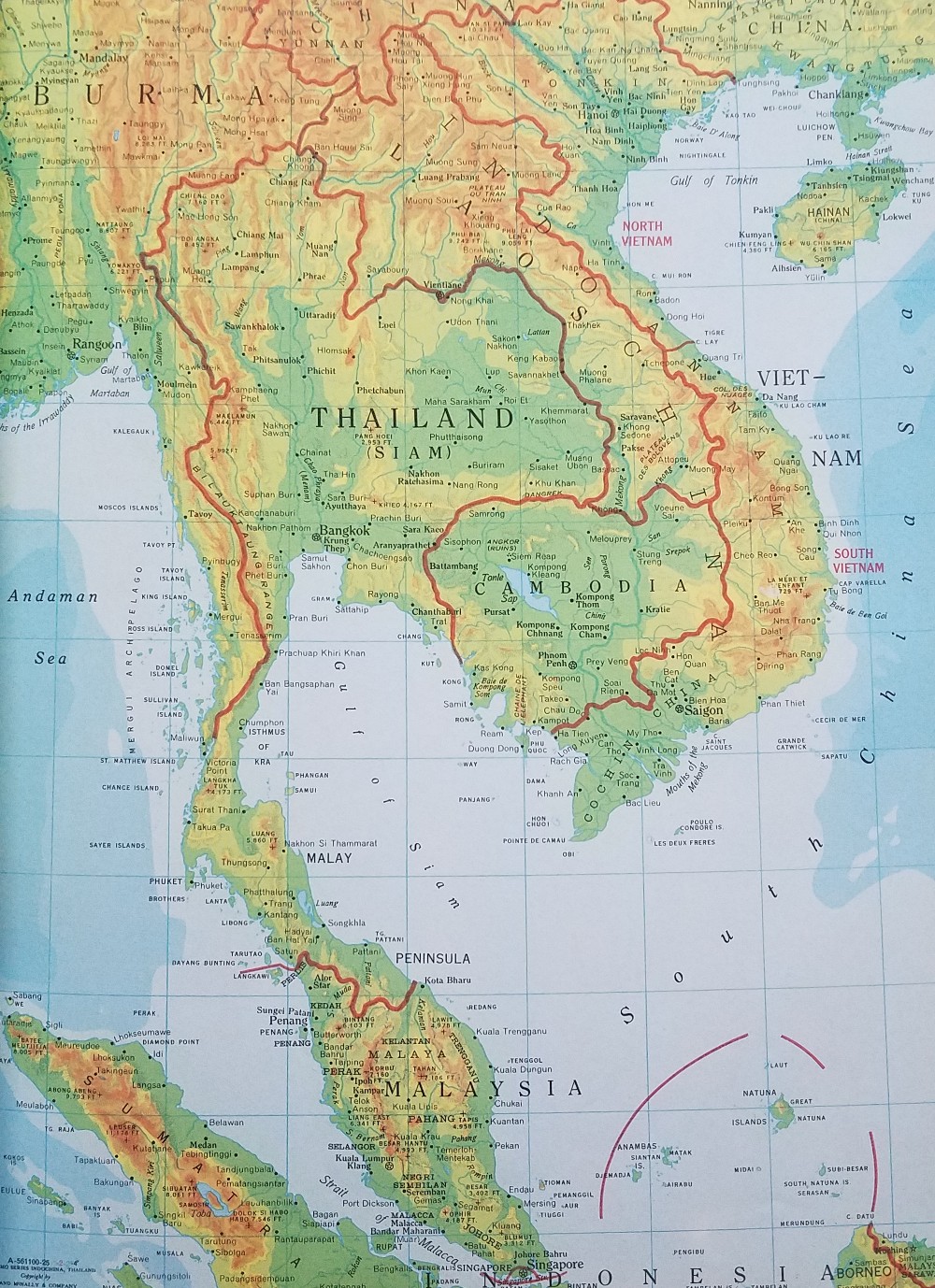

On April 30, President Nixon announced that U.S. troops had entered Cambodia, expanding the war in Southeast Asia. This sparked mass May Day protests across the country. After the Kent State ROTC building was burned down over the weekend, Kent Mayor LeRoy Satrom asked Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes to dispatch the National Guard to the campus.

Clashes between students and law enforcement escalated, with several students reportedly being stabbed by guardsman bayonets. Calls for the Guard troops to be recalled were refused. This set the stage for Monday's tragedy.

It is not certain what triggered the firing. Eyewitnesses said about 600 protestors surrounded a company of 100 Guardsmen and began pelting them with rocks and hunks of concrete. A single shot rang out, whether from a guardsman's rifle or someone else's firearm, is unknown. Without a warning, the guardsmen then began a three second volley, half of them pointing their guns into the air, the other aiming levelly—into the milling crowd of boys and girls.

Amont the dead were William K. Schroder, 19, a sophomore from Lorain, Ohio; Jeffery Miller, 19, a freshman from Plainview, New York; Sandra Lee Scheuer, 20, a junior from Youngstown, Ohio; and Allison Krause, a 19-year-old freshman from Pittsburgh. John Cleary, 19, a freshman from Scotia, New York; Dean Kahler, a 20-year-old freshman from East Canton, Ohio; and Joseph Lewis, just 18, from Massillon, Ohio, were reported in critical condition at Robinson Memorial Hospital in nearby Ravenna. They were not all protestors—indeed, Miss Krause had just telephoned her parents to express disgust at the demonstration.

A wave of new protests is wracking the country, now with fresh ammunition. And it is ammunition that is at the center of this outrage, for the Guard did not use tear gas, rubber bullets, or blanks. Never mind if they should have been on the campus at all. At the very least, their rules of engagement should not have incurred collateral deaths on innocent students.

There are just two positive consequences of this tragedy. The first is that if the goal of calling in the Guard was to cow protestors, it has backfired spectacularly. The second is that, on May 5, President Nixon announced that American troops would be withdrawn from Cambodia in seven weeks. How much this decision is in reaction to the demonstrations and how much is due to the heavier-than-expected resistance of the Communists is presently unknown.

I suppose there's one more result—I've been radicalized, and I plan to start marching. It's something I've always supported in the abstract, but observed a modicum of restraint, recalling Tom Lehrer's sentiment, "It takes a certain amount of courage to get up in a coffee house or college auditorium and come out in favor of the things that everybody else in the audience is against – like peace, and justice, and brotherhood, and so on."

But now we see that the audience doesn't all agree, and some of them shoot. I know I'm in the over-30 untrustworthy set, but you'll see my grizzled mug in among the protestors in the weeks to come.

Congratulations, Dick—you managed something Lyndon couldn't.

Shards

And so I plunge into fiction, hoping for a relief from the growing madness. I am greeted with more madness: each of the stories in The latest issue of Galaxy is broken into pieces, with their ends crammed into the latter half of the magazine, as if written like some strange BASIC program with too many GOTO commands. Nevertheless, it's the stories that count. How are they?

cover by Jack Gaughan illustrating The Moon of Thin Reality

Continue reading [May 8, 1970] Tower of Glass (June 1970 Galaxy)

![[May 8, 1970] Tower of Glass (June 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/700508galaxycover-645x372.jpg)

![[April 30, 1970] Praise for the Resident Witch (May 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700430analogcover-672x372.jpg)

![[April 28, 1970] A Strange Case of Vulgarity & Violence (<i>Vision of Tomorrow</i> #8)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/VoT5-1-280x372.jpg)

![[April 20, 1970] Not the final quarry (May 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700420fsfcover-653x372.jpg)

![[April 14, 1970] Take this spaceship to Alpha Centauri (May 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Venture-1970-05-Cover-475x372.jpg)

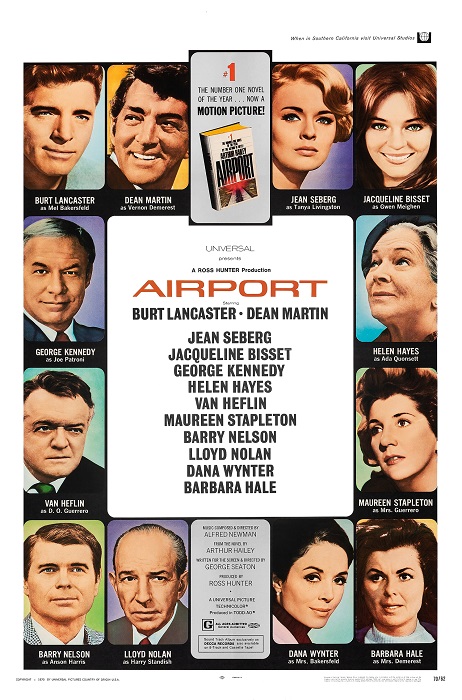

You probably know who most of these people are.

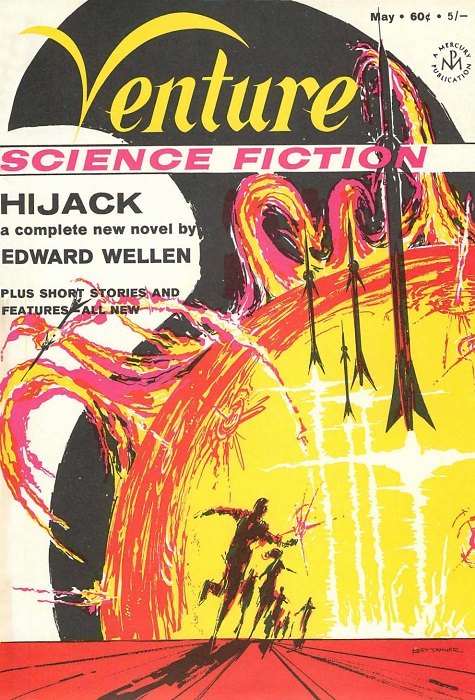

You probably know who most of these people are. I’m still not sold on Tanner’s covers, but this one is better than most. Art by Bert Tanner

I’m still not sold on Tanner’s covers, but this one is better than most. Art by Bert Tanner![[April 10, 1970] A Style in Treason (May 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700410galaxycover-651x372.jpg)

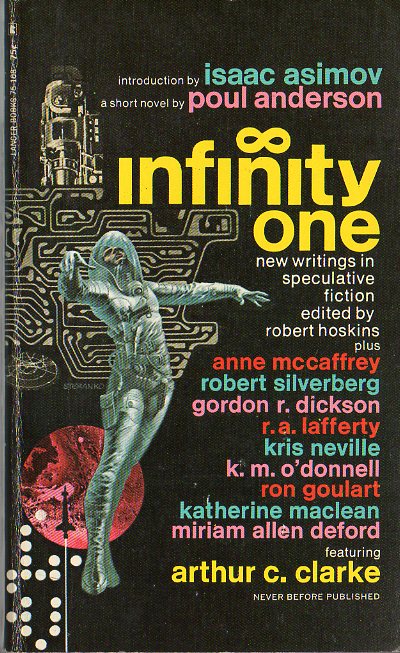

![[April 8, 1970] All Too Finite (<em>Infinity One</em>, edited by Robert Hoskins)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ANCL00221-400x372.jpg)

![[April 6, 1970] Uncovered (May 1970 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/amz-0570-cover-672x372.png)

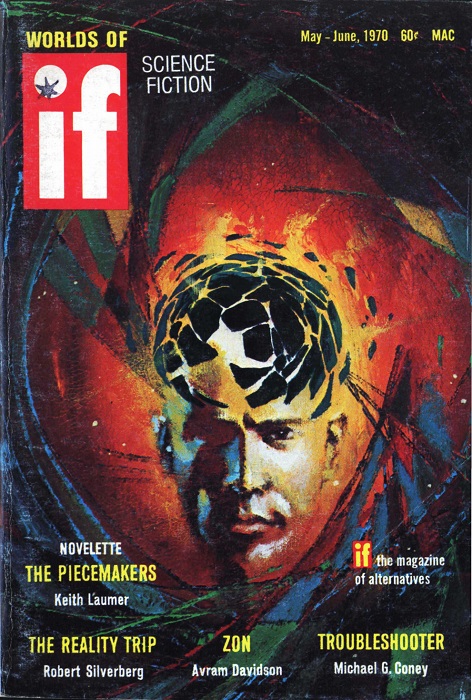

![[April 2, 1970] Being Human (May-June 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IF-1970-05-Cover-472x372.jpg)

Archbishop Makarios III visiting the Greek royal family in exile in Rome earlier this year.

Archbishop Makarios III visiting the Greek royal family in exile in Rome earlier this year.

l: Prince Sihanouk in Paris shortly before his ouster. R: Prime Minister Lon Nol.

l: Prince Sihanouk in Paris shortly before his ouster. R: Prime Minister Lon Nol. Suggested by Troubleshooter. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by Troubleshooter. Art by Gaughan![[March 31, 1970] Seed stock (April 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700331analogcover-672x372.jpg)