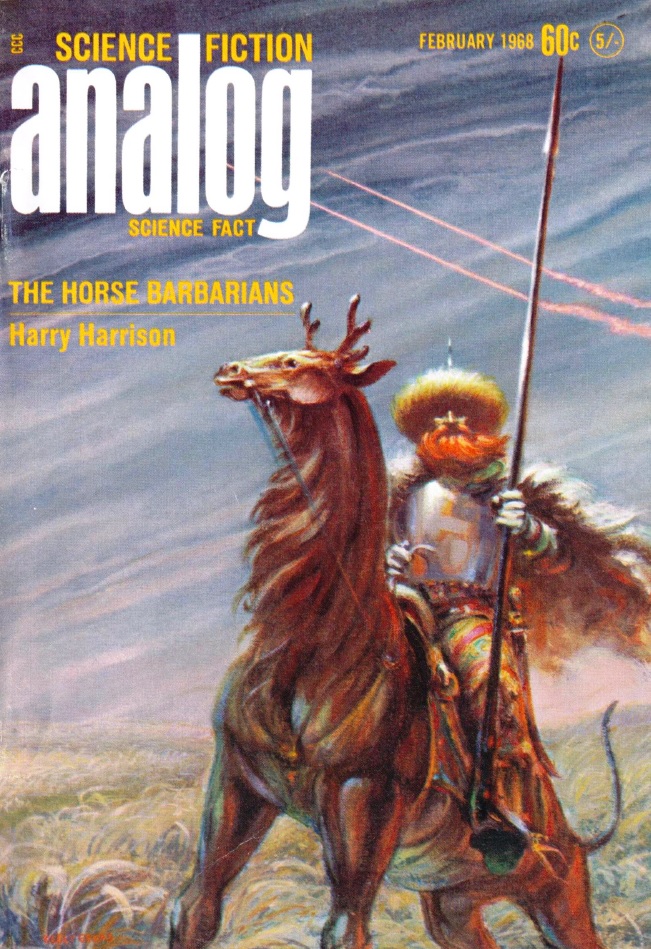

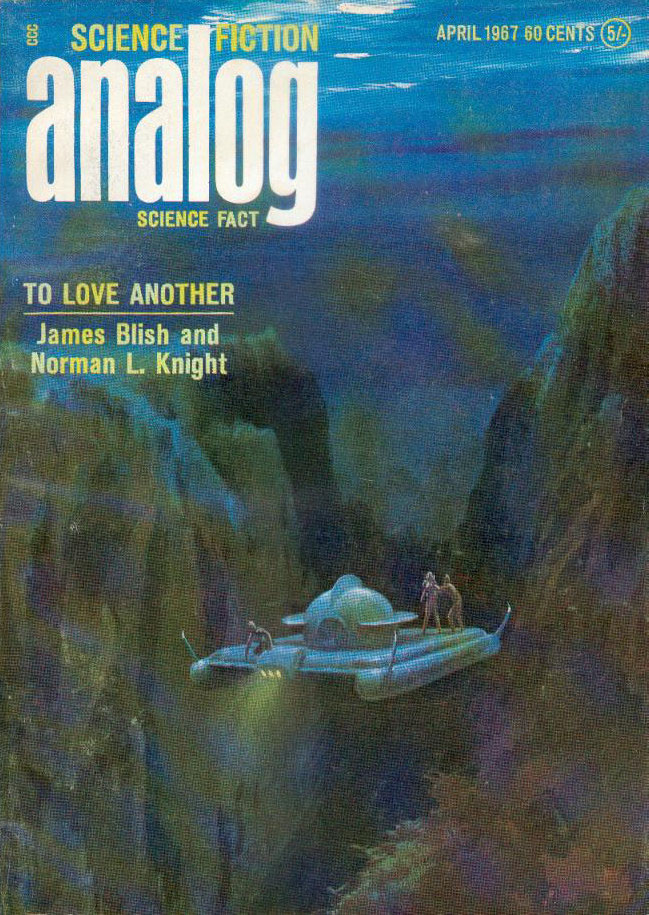

by Gideon Marcus

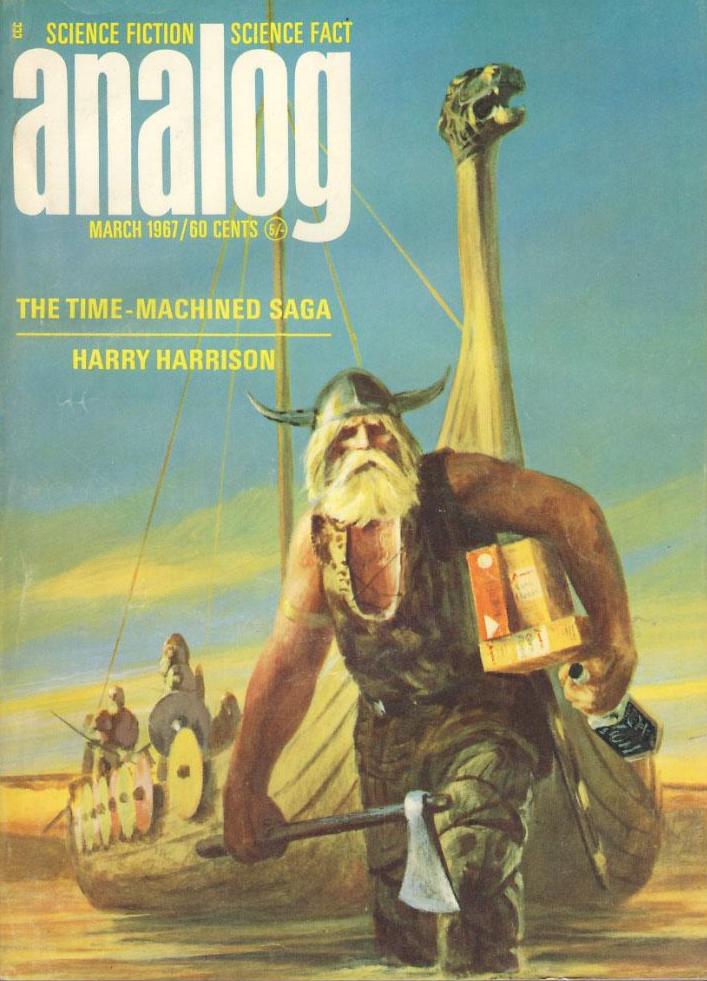

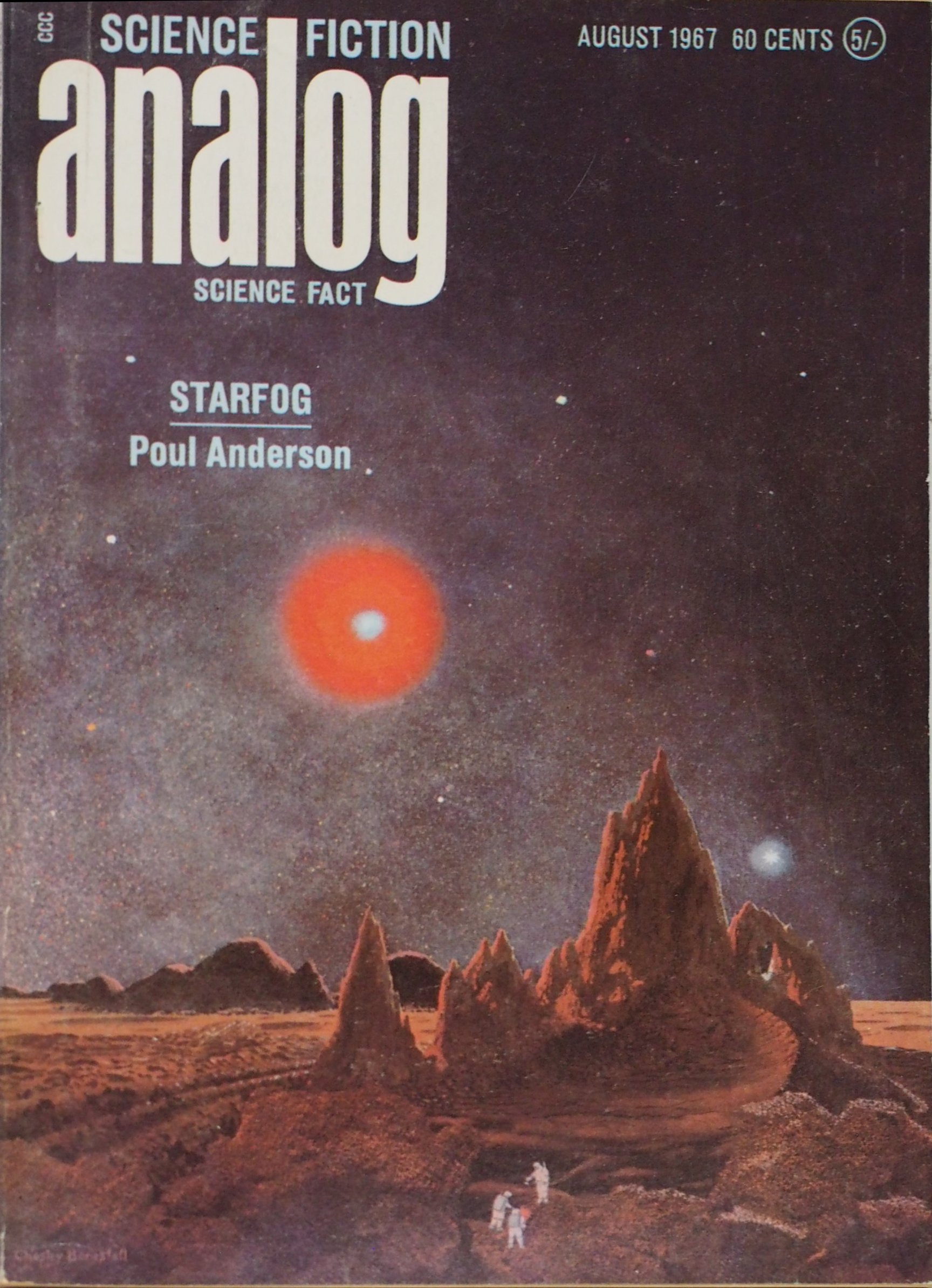

There are all kinds of science fiction stories. Some explore the human condition, prioritizing people and how they might be affected by emerging technologies. Others are space or planetary adventures, utilizing an exotic locale as backdrop for classic derring-do.

Analog (formerly Astounding) has always emphasized technological pieces. They are stories of gadgets, of scientific implementations, not people. Even better is when the story underscores the libertarian, rather reactionary politics of one editor John W. Campbell Jr.

Sometimes, a skilled writer can get a story into Campbell's mag without that kind of tale. In this issue, virtually none of them did…

The issue at hand

by Kelly Freas

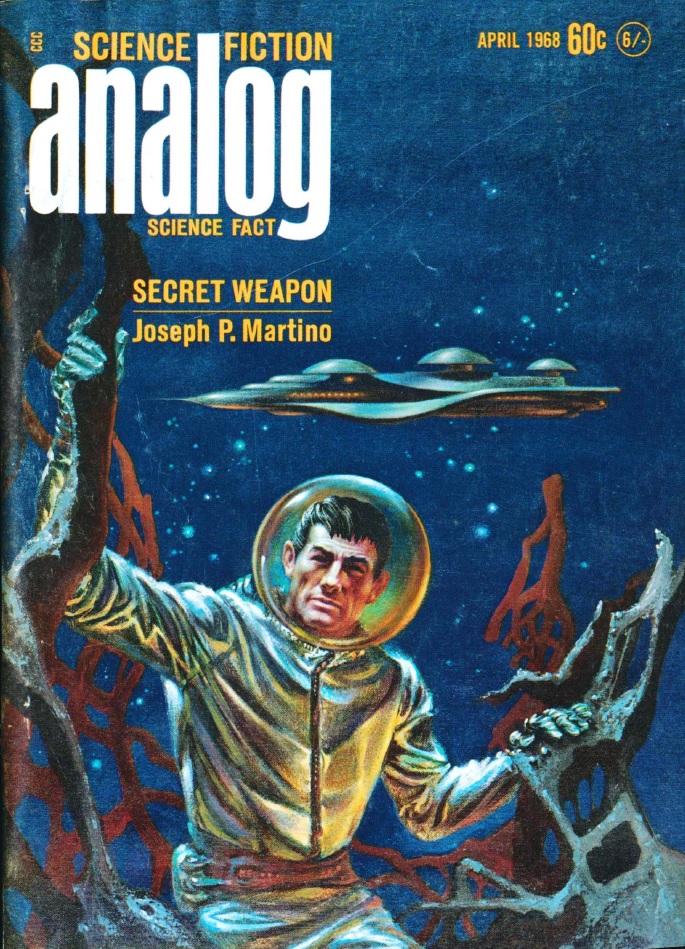

Secret Weapon, by Joseph P. Martino

The interstellar war against the Arcani is going badly. Now that the Terrans have doubled their Patrol Corvette fleet, suddenly their losses have quadrupled. Somehow, the alien enemy is tracking down their gravitational signatures as they zoom through their patrol lanes at four times the speed of light–and even when the human crews manage to intercept the enemy warships, somehow they elude destruction.

Two ships are dispatched to find the answer to this crisis, equipped with a new nucleonic clock that allows the ships to communicate even at superluminary speeds. Now they can cover each other in case of attack. When attack inevitably comes, they discover the secret to the enemy's success.

Joe Martino probably enjoyed writing this novella, and John Campbell obviously enjoyed reading this novella, so I suppose the story must be called some kind of success. However, if you don't enjoy things that read like the centerfold to a particularly dry issue of Popular Gravitics, I suggest you give this one a skip. This probably could have been a great novel, with time devoted to, you know, characters and prose, as opposed to a thinly dressed up engineering problem whose solution is implied to be beyond the comprehension of the alien foe.

Two stars.

Handyman, by Jack Wodhams

by Leo Summers

A married couple, trapped on a muddy world with virtually no trappings of civilization, try to make even the most basic rudiments of technology to ease their plight. Eventually, they figure out how to make ceramics, and when a rescue party finally appears, they are now happy to stay on their private world and even to start an export trade of their new kind of china. Chalk up a win for enforced entrepreneurialism!

I kept waiting for Wodhams to explain how the planet-wrecked pair figured out how to make their ceramic, given that all the ways that didn't work were so lovingly detailed.

Still, the story is at least readable. A low three stars.

Phantasmaplasmagoria, by Herbert Jacob Bernstein

by Kelly Freas

According to the scientists, power from nuclear fusion, harnessing the union of hydrogen atoms to produce boundless electricity, is just twenty years away. This story details the meandering road to the technology's serendipitous development.

It's a silly piece, and I'm not sure who thought it a good idea to put a fourth of the story in endnotes that one has to constantly refer to. They aren't worth the pay-off.

Two stars.

Is Everybody Happy?, by Christopher Anvil

by Leo Summers

A hay fever drug has the unfortunate side effect of making everyone extra-friendly. Society breaks down as folks would rather kibbitz than work.

It says something about Analog and its editor's beliefs that too much friendliness will obviously lead to economic ruin, as opposed to increased efficiency through greater cooperation. Call me crazy, but I work better when I like my co-workers.

Anyway, this is another "funny" piece by Anvil for Campbell, and it's as good as you'd expect it to be.

Two stars.

Incorrigible, by John T. Phillifent

by Leo Summers

A naval officer is up for treason, having facilitated the transfer of technical knowledge to the Drekk, potentially Earth's most dangerous foe. The implacable lizards, inhabitant of a Venus-type planet (nicknamed "Wet" for its torrid, humid conditions) are incredibly quick studies, and interstellar spaceflight is only a few developments away.

But, the officer notes, at the end of a very long dialogue with his attorney (the sole point of which is to build to the punchline conclusion) the information leak was ultimately to humanity's benefit. For it involves the ability to teleport water, which the Drekk will use to colonize the nearby planet, "Dry". And once enough mass is teleported from Wet, the core will explode, destroying the evil aliens.

Well.

I can't imagine this is particularly sound science, this notion that Venus-type planets are at a critical point such that the lost of a few million tons of water can destabilize them, especially coming from a fellow who still characterizes Venus as "wet" five years after Mariner 2. That notwithstanding, I might have been more tolerant, given the decent writing in this piece, if the author (under his pseudonym) had not used the exact same gimmick to end his recent novel, Alien Sea!

Two stars.

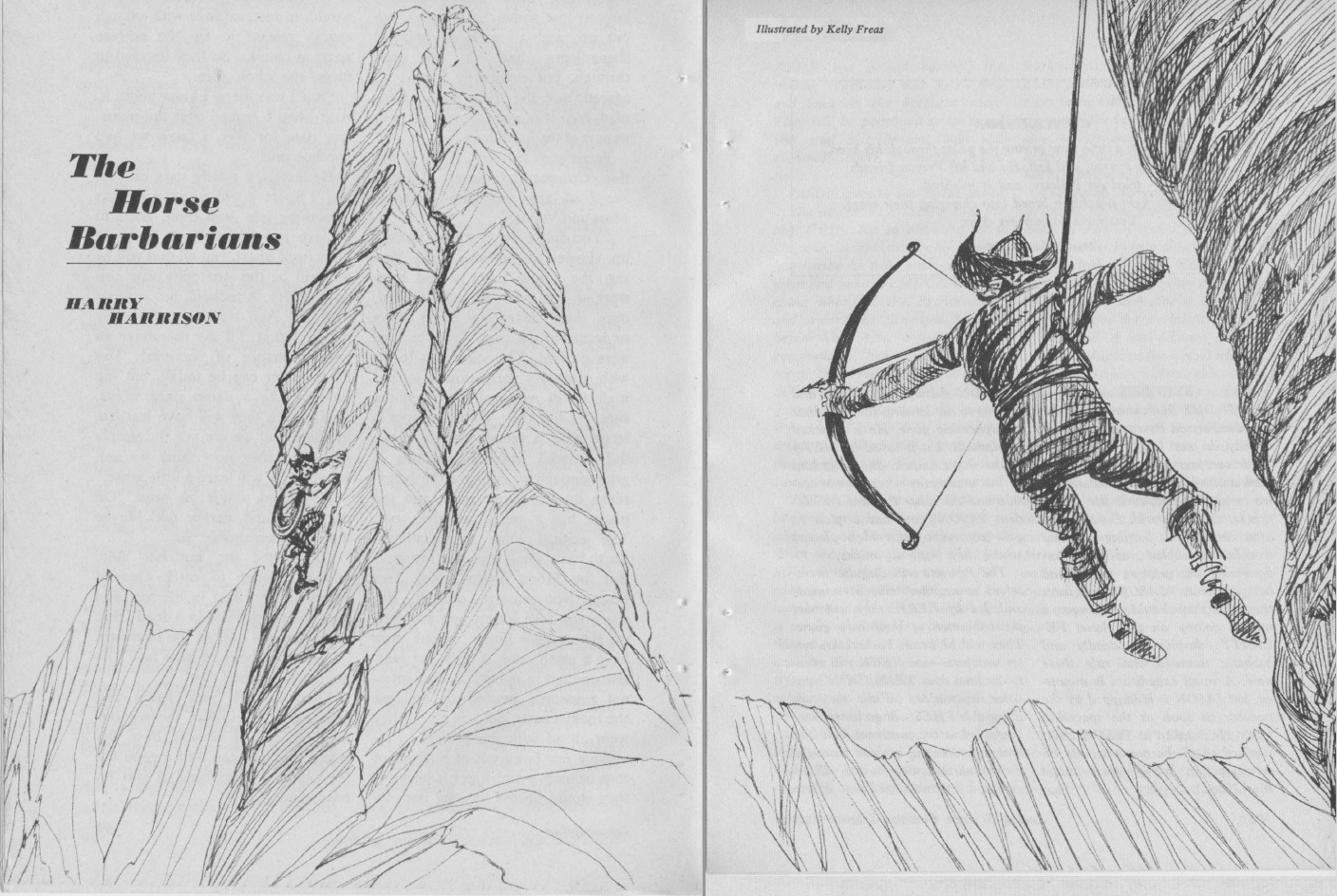

The Horse Barbarians (Part 3 of 3), by Harry Harrison

by Kelly Freas

Jason dinAlt's adventures appear to have come to an end with this third Deathworld novel. By the end of the story, the Pyrran city has been destroyed by the planet, the horse barbarians of Felicity have been defeated, and Meta and Jason have finally professed their love for one another.

How is Temuchin, highest chief of the Felicitan nomads defeated? After Jason is found out for the outworlder he is, the barbarian tosses him into a deep pit to die. Instead, Jason finds his way through a maze of caves, discovering a passage from the frozen steppes to the rich lowlands. All other methods of toppling Temuchin having failed, Jason tells the warlord the secret of the caves so that the barbarians can finally conquer the whole continent.

Almost immediately, Temuchin realizes his victory is really defeat, for taking all the cities means the inevitable death of the nomad way of life. The nomads collapse within weeks, and the Pyrrans set up shop.

There are a lot of problems with this book. Temuchin is supposed to be this awful, violent savage for slaughtering foreign invaders, and for wanting to take out the lowlanders. Does this justify the Pyrrans in killing and facilitating the killing of far more people than Temuchin ever could have managed on his own?

Beyond that, the historical "lesson" at the end of the story is specious. Sure, the Chinese sinicized the Mongols, but not all of them, and not in a matter of weeks. And as for the Goths and Huns (also cited), the former were invited to settle the Roman Empire rather than becoming Roman after conquering, while the Huns were simply defeated in fight after fight.

Thus, I find Jason's actions and motivations more ruthless and inhuman than Temuchin's; they are also out of keeping with the peacenik environmental message so beautifully expressed in Deathworld.

All that said, there's no question that Harrison is a terrific writer (he almost makes you accept the unrealistic extents to which Jason pushes his body). I turned to this serial first each of the last three months, and I finished each installment in a sitting. As a result, while I give this segment three stars, and even though I find the premise repugnant, I still am giving the novel as a whole three and a half stars.

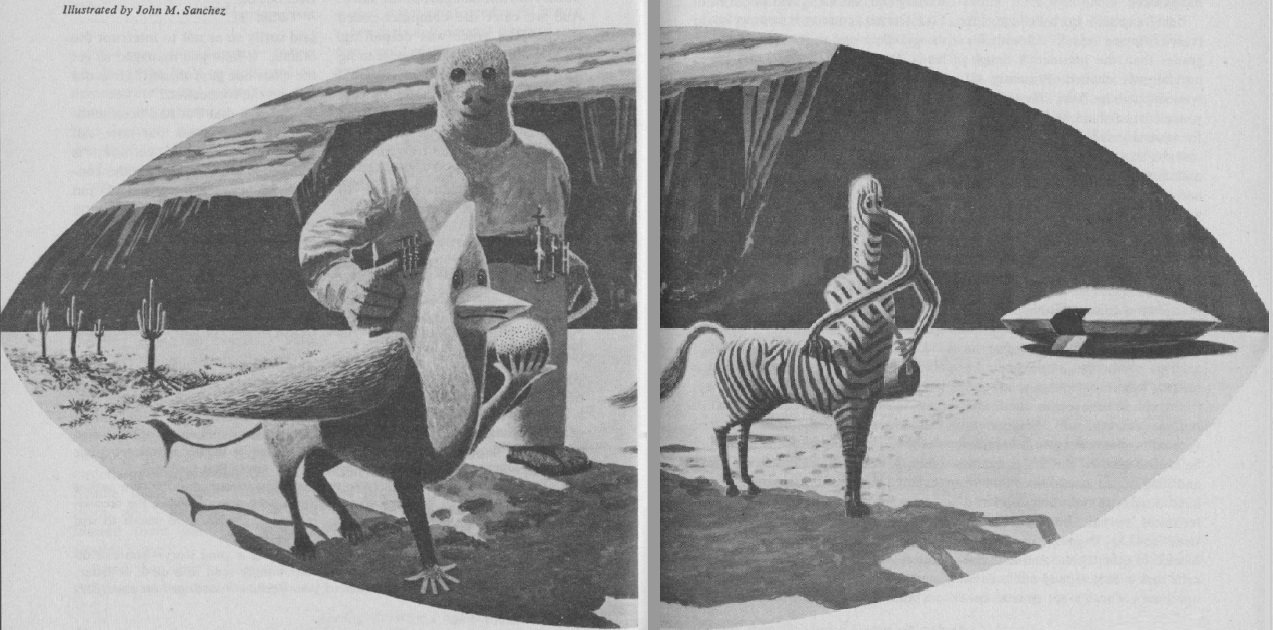

Local Effect, by D. L. Hughes

by Leo Summers

An alien space drive discarded near Earth's moon has drastic effects on human scientific development. It turns out that the speed of light is not a constant…except around Earth. Thus, Einstein's theory of relativity only describes a local phenomenon, not the universe as a whole. Alien anthropologists from a faraway star survey humanity and note this local aberration with interest.

This is an interesting premise, but Hughes, knowing his audience (a certain editor named Campbell), turns it into an anti-scientific-establishment polemic, noting that, if only humans were a little more broad minded, they might not have gotten stuck in their rut. After all, how dare we assume that the rules that hold locally apply to the whole universe?

Except, of course, that is the very soul of the scientific method. Moreover, observations this century make it clear that relativity does hold throughout the universe–as early as 1919, just four years after the publication of General Relativity, light was seen to have been deflected around the sun's gravity well, pursuant to theory.

This could have been a fascinating story of aliens assuming that all beings should follow an "obvious" course of scientific development, deluded by their own understanding of all the facts. Instead, we get…this.

Two stars.

Doing the math

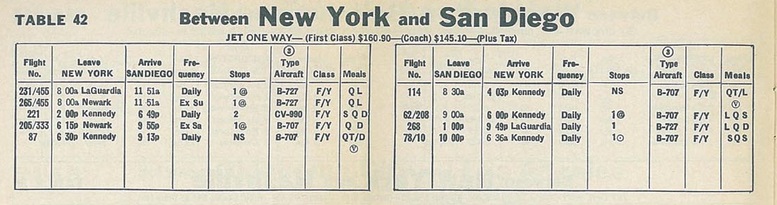

If it's a race to the bottom, Analog has won handily, scoring just 2.3 stars this month. This accomplishment is all the more sad when one realizing that this is a better score than it got last month!

Luckily, the other magazines of the month were somewhat better, including New Worlds (2.8), New Writings 12 (3.1), Famous Science Fiction #4 (2.9), Famous Science Fiction #5 (2.5), Famous Science Fiction #6 (2.7), Fantasy and Science Fiction (2.7)

IF (3.1), and the best, Galaxy (3.3).

Women penned just 4% of the new fiction this month, and even with all the issues of Famous (lumped due to logistics into this one month), there was still only 2.5 to 3 issues' worth of superior stuff.

I guess we'll see if the Pohl mags continue to reign, or if all fortunes oscillate. I think it's safe to say, though, that Analog could definitely use a loosening of its editorial prescriptions. Hope springs eternal!

![[March 28, 1968] Design for effect (April 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/680328cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 31, 1968] Too much and too little (February 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680131cover-651x372.jpg)

![[December 10, 1967] Give 'Em Hell, Harry! (January 1968 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/COVER-ART-3-672x372.jpg)

![[October 8, 1967] Things Fall Apart (November 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Fantastic_v17n02_1967-11_0000-3-672x372.jpg)

![[September 30, 1967] Ain't that good news! (October 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/670930cover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 31, 1967] I wouldn't send a knight out on a dog like this… (September 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670831cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 31, 1967] Canceling waves (August 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670731cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 10, 1967] Music To Read By (July 1967 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/fantastic_196707-2-1.jpg)

![[March 28, 1967] At last, a drop to drink (April 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670328cover-649x372.jpg)

![[February 28, 1967] The Big Stall (March 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670228cover-672x372.jpg)