by Cora Buhlert

Whale Hunt on the Rhine

All of West Germany is currently kept on tenterhooks by Moby Dick. No, I'm not talking about the classic novel by Herman Melville, but about our very own re-enactment thereof on the river Rhine.

On May 18, the skipper of a Rhine barge reported having seen "a white monster" in the polluted waters of the Rhine near Duisburg. The river police initially assumed that the man was drunk, but other sightings were reported as well. The unfortunately named Dr. Wolfgang Gewalt (his surname literally means "violence"), director of the Duisburg Zoo, identified the creature as a beluga whale, which had somehow managed to swim 450 kilometres upstream.

Discovering his inner Captain Ahab, Dr. Gewalt decided to capture the white whale and have it transported to his brand-new dolphinarium. However, he was about as successful as his literary counterpart and so Moby Dick, as the whale was nicknamed by the locals, repeatedly eluded the traps laid for him, with the aid of some people who believe that the whale should be free back to swim the ocean and not imprisoned in a too small basin.

Eluding his would-be captors, Moby Dick even swam as far upstream as the West German capital of Bonn, where he interrupted a parliamentary press conference, most likely to protest the treatment he had suffered at the hands of the West German police as well as the heavy pollution of the Rhine, which turned the pristine white skin of a whale a splotchy grey. However, there is a happy ending, because Moby turned around and made it back to the North Sea unharmed.

All-new Anthology, All-new Stories:

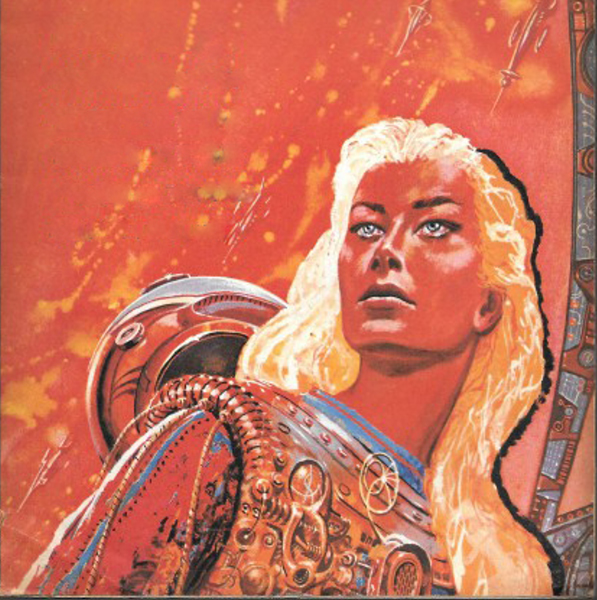

Moby's adventures are enough to keep the entire country at the edge of their seats. But nonetheless, I still found the time to read the new science fiction anthology Orbit 1, edited by Damon Knight, which I picked up from the trusty spinner rack at my local import bookstore. The blurb on the backcover promised nine brand-new stories by the best science fiction authors working today, so how could I resist?

"Staras Flonderans" by Kate Wilhelm

Kate Wilhelm is not only one of the best up and coming science fiction authors, she also happens to be married to Orbit editor Damon Knight. That said, Knight wasn't playing favourites here, because Kate Wilhelm's contribution to the anthology is a genuinely good story.

A scout craft with a three person crew, two humans and the alien Staeen, approaches a derelict starship. The lifeboats are gone and the ship was abandoned by her crew in a hurry. However, our three brave explorers have no idea why, since the ship was in perfect working order. Nor is this the first time something like this has happened; other ships have been found abandoned as well.

Kate Wilhelm explores the mystery of the abandoned starship not through the eyes of the two human crewmen, but of the alien Staeen, who is described as looking like an inverted tulip at one point. Staeen is a truly alien creature, who can survive on land, underwater, in deep space and in high radiation environments. He is an empath, several millennia old and humans are ridiculously short-lived to him. In fact, Staeen's people, the Chlaesan, refer to humans as "Flonderans", which means "children" in their language. Staeen's human crewmates, two big, burly spaceman that would be at home in any issue of Analog, clearly have no idea how their comrade views them.

Staeen uses his empathic abilities and realises that the crew abandoned the ship in a fit of irrational panic. But whatever caused that blind panic is still out there, as our three brave explorers are about to find out…

At its heart, this story is a neat mystery in space that would have been at home in Planet Stories or Thrilling Wonder Stories twenty years ago. What sets it apart is Staeen's uniquely alien view of the world as well as Kate Wilhelm's writing skills.

Four stars.

"The Secret Place" by Richard McKenna

I wasn't familiar with the work of Richard McKenna, who passed away two years ago at the way too early age of fifty-one. So "The Secret Place", which was found among his papers after his death, is my first exposure to his work.

First-person narrator Duard Campbell recounts his strange wartime adventures. As a young geology student, Campbell was part of a team that was supposed to track down a uranium mine in the Oregon desert. For in 1931, a boy named Owen Price was found dead with claw marks on his back as well as some gold ore and a piece of uranium oxide in his pocket. When uranium suddenly becomes vitally important with the onset of WWII, the US Army sends a team to locate the source of the uranium oxide. The chief geologist Dr. Lewis believes that this venture is futile, because the area in question is a volcanic high plateau, where uranium does not naturally occur.

When the team departs, only Campbell is left behind. He wants to prove Dr. Lewis wrong and find the uranium vein. So he hires Owen's sister Helen, who can see things no one else can see, as his secretary to pry the secret of the uranium mine out of her. But the game Campbell plays with Helen quickly becomes dangerous for them both.

I enjoyed the vivid descriptions of the Oregon countryside, though I have no idea how accurate they are. The ending is a bit abrupt, though, and the central mystery is not really resolved, probably because McKenna died before he could finish the story.

Three stars.

"How Beautiful With Banners" by James Blish

James Blish needs no introduction to the readers of the Journey.

Dr. Ulla Hillstrøm is a scientist who runs into problems when her living spacesuit merges with a native creature, described as a floating cloak, during a research mission of the Saturn moon of Titan.

Dr. Hillstrøm realises that the cloak is trying to mate with her spacesuit. She notes a second cloak creature and deduces that it might be jealous, so she tries to use the second creature to separate the cloak creature from her spacesuit. However, she is only partly successful, because the separation destroys the spacesuit. The last thing Dr. Ulla Hillstrøm sees before she freezes to death is the mating dance of the cloak creatures.

Beautifully written, but inconsequential. The stereotype of the icy female scientist who never knew love and companionship is overused. Science fiction writers, please go and meet some actual women scientists.

Two stars

"The Disinherited" by Poul Anderson

Poul Anderson is another author who needs no introduction.

The government of an overpopulated future Earth ends the galactic exploration program and recalls scientific personnel and spaceship crews. Understandably, no one is very happy about this.

"The Disinherited" follows two characters. Jacob Kahn is a starship captain and has been for a very long time due to the time dilation effect of travelling at lightspeed. Kahn is also an Israeli Jew, something which should not be unusual, considering how many science fiction writers are Jewish, but which sadly still is. Kahn's first mate is Native American, his chief engineer is from India, the assistant chief engineer from Africa. Anderson presents us a still all too rare future populated by people other than white Anglo-Saxon Protestants, though most of them are still male.

David Thraikill is a scientist whose family has been living on the planet Mithras for three generations now and who has never been to Earth. As a result, Thraikill and the rest of the scientists do not want to leave Mithras, because this is their home now. Kahn tries to persuade them to leave by explaining that the human inhabitants of Mithras cannot maintain a high level of technology in the long run and that there will also be conflicts with the native population of Mithras, a race of peaceful kangaroo-like beings. Because as history shows, this is what always happens when one group of humans comes in contact with another group and colonises their homeland…

Considering how prolific Poul Anderson, it's no surprise that his works can be hit and miss. "The Disinherited" definitely falls on the "hit" side and offers a look at the dark side of colonialism, something our genre rarely explores.

Five stars

"The Loolies Are Here" by Allison Rice

Allison Rice is the only unfamiliar name in Orbit 1. However, the biographic note explains that Allison Rice is a joint penname used by Jane Rice, whose stories have been brightening up the pages of Unknown, Astounding and F&SF for more than twenty years now, and Ruth Allison, a mother of five and new writer.

The first person narrator – we later learn that she shares the name the authors have chosen to publish this story under – is a harried housewife and mother of four, who is dealing with a torrent of bad luck, appliances breaking down, children and pets misbehaving, etc… One day, she finds tiny footprints on the floor and wonders whether the loolies – mischievous goblins whom her sons blame for their own misbehaviour – are not real after all. Eventually, the narrator sees a bonafide loolie in the bathroom during a massive storm. But even though the loolie causes chaos, he does help the narrator get even with her useless husband.

"The Loolies Are Here" is very much a humour piece and the voice of the harried housewife and mother certainly rings true. In many ways, this story reminded me of Shirley Jackson's collection of semi-autobiographical short stories Life Among the Savages. It's a good story, but as a humorous domestic fantasy story, it doesn't really fit into what is otherwise a science fiction collection.

Four stars

"Kangaroo Court" by Virginia Kidd

Virginia Kidd is a well known name in genre circles as a member of the Futurians, poet, magazine publisher, literary agent, former roommate of Judith Merril and former wife of James Blish. Now she can also add short fiction writer to her resume.

A future Earth, where war is a thing of the past and space travel has been outlawed, receives strange messages from outer space, followed by the landing of a spaceship. A military officer named Tulliver Harms puts himself in charge of dealing with the alien Leloc, whom he is convinced must be dangerous – after all, they're aliens. Harms plans to annihilate the Leloc.

The only potential obstacle to this plan is the newly appointed liaison officer Wystan Godwin, who had no idea what is going on due to having spent the past few months on a retreat in monastery in Tibet. Harms does his best to keep Godwin busy and in the dark, but eventually Wystan gets to parley with the kangaroo-like Leloc, who are not just very alien, but who also believe that Earth is their long lost colony. Wystan has to muster all his diplomatic skills to avoid genocide or all-out war.

"Kangaroo Court" is an amusing story about how diplomacy rather than violence wins the day, featuring some truly alien aliens. However, it also goes on far too long and particularly the expositional sections in the middle about kangaroos, marsupials and the impossible nature of the Leloc spacedrive made my eyes glaze over like the gizmospeak in a bad Analog story.

Three stars

"Splice of Life" by Sonya Dorman

Sonya Dorman burst onto the scene a few years ago and has since established herself as one of our most exciting new writers.

"Splice of Life" opens with a young woman – she's only ever addressed as Miss D. – coming to after a car accident, just in time for a doctor to stick a hypodermic into her eyeball. The eye was injured in the accident and Miss D. worries that she may lose it. The doctors and nurses reassure her, but both Miss D. and the reader realise that something is not quite right in this hospital.

A neat tale of medical horror with a ending that packs a punch.

Four stars

"5 Eggs" by Thomas M. Disch

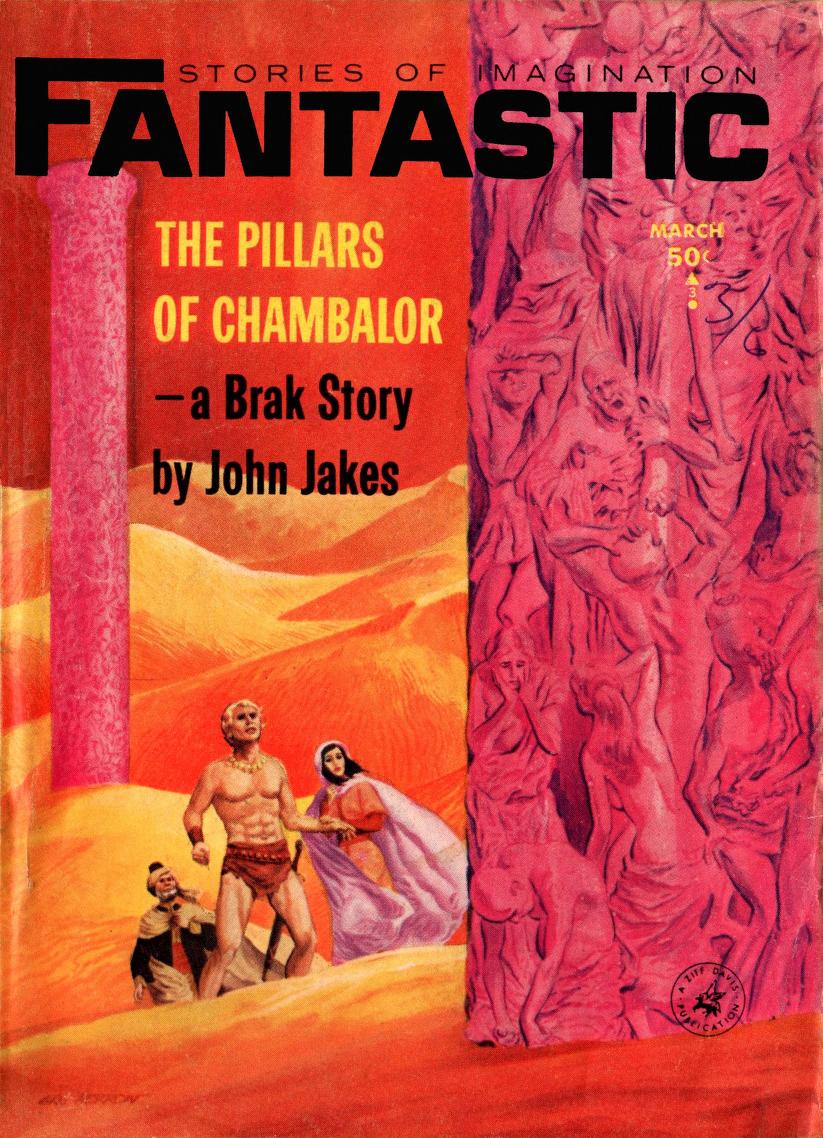

Thomas M. Disch is another newish author, who was one of Cele Goldsmith-Lalli's discoveries back when she was editing Fantastic and Amazing.

The unnamed writer protagonist of "5 Eggs" has been left by his lover Nyctimene on the eve of their engagement party. Gradually, we learn that Nyctimene was not quite human, but some kind of bird alien, as the reference to the figure from Greek mythology suggests. However, Nyctimene has left something behind: a basket of eggs. But leaving eggs lying around the house can be quite dangerous.

This story is well written, but there isn't much of a plot and the final twist is not as shocking as Disch probably thinks it is. The recipe for Caesar salad sounds good, though.

Two stars

"The Deeps" by Keith Roberts

British writer and artist Keith Roberts has been gracing the covers and pages of Science Fantasy and New Writings in SF for several years now, though this is his first US publication, as far as I know.

"The Deeps" starts with the by now familiar dystopian vision of an overpopulated Earth (for another recent take on this theme see Make Room, Make Room! by Harry Harrison, reviewed here by our own Jason Sacks). This time around, the ingenious solution to the overpopulation problem is cities on the ocean floor.

Mary Franklin is a suburban housewife living in one of those undersea cities. One day, her teenaged daughter Jen goes off to a dance and doesn't come home. Mary goes searching for her, wondering whether the children who grow up under the sea are not becoming steadily more fishlike.

"The Deeps" is well written. Roberts captures both Mary's frustration with her husband and her fear for Jen, though I wonder whether a frantic mother searching for her missing child would really spend two pages describing the infrastructure of undersea living. Atmospheric, but not a whole lot of plot and marred by long stretches of exposition.

Three stars

Summary Judgment

The Orbit anthology series is certainly off to a good start. The quality of the stories varies, but they do offer a good overview of the range of science fiction writing today.

Of the nine stories in this anthology, four are written by women. If we count Jane Rice and her collaborator Ruth Allison separately, we have five male and five female authors. Of course, women make up fifty-one percent of the Earth's population, so an anthology with fifty percent male and fifty percent female contributors shouldn't be anything unusual. However, in practice there are still way too many magazine issues and anthologies that don't have a single female contributor, so an anthology where half the authors are women is truly remarkable.

Three and a half stars all in all

![[June 14, 1966] Aliens, Housewives and Overpopulation: <i>Orbit 1</i>, edited by Damon Knight](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ORBIT11966-270x372.jpg)

![[January 18, 1966] New Discoveries of the Old (<i>Out of the Unknown</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Out-of-the-Unknown-Titles.jpg)

![[February 22, 1965] Theory of Relativity (March 1965 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Fantastic-v14-n03-1965-03_0000-3-672x372.jpg)