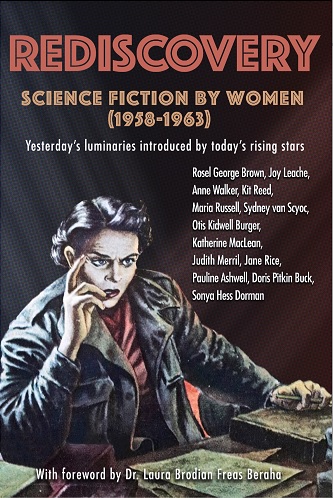

[We have exciting news! Journey Press, the publishing company founded by the team behind Galactic Journey, has just launched its first book. We know you will enjoy Rediscovery: Science Fiction by Women (1958-1963), a curated set of fourteen excellent stories introduced by the rising stars of 2019.

If you enjoy Galactic Journey, you'll want to purchase a copy today — available physically and virtually!]

by Gideon Marcus

It's a War, Man

No matter which way you look these days, fighting has broken out somewhere. Vietnam? War. The Congo? War. Yemen? War.

Worldcon? You'd better believe it's war.

Back in May, the committee putting on this year's event (in Oakland, called Pacificon II) decided that Walter Breen would not be allowed to attend. For those of you living in a steel-plated bubble, Breen is a big-name fan in the SF and coin-collecting circles with a gift for inciting dislike in direct proportion to one's proximity.

Oh, and he's also a child molester.

Now there has been much gnashing of teeth and rending of garments over the draconian action taken by the Pacificon committee, likening the arbitrary action to McCarthy's witch trials of the last decade. As a result, fandom has largely resolved itself into two camps, one defending the attempt to evict Breen from organized fandom, the other vilifying it.

I know we're a kooky bunch of misfits and our tent should be pretty inclusive, but ya gotta draw the line somewhere, don't you? And what may have been fine for Alexander doesn't hold in the 20th Century. I guess it's clear which side I fall on.

Well, despite the protests and the boycotts that tainted the Worldcon (which were part of what deterred me from attending this year), they still managed to honor what the fans felt was the best science fiction and fantasy of 1963. Without further ado, here's how the Hugos went:

Best Novel

Here Gather the Stars, by Clifford Simak (63 votes)

Nominees

For the first time, the Journey had reviewed all of the choices for Best Novel before the nominating ballots had even been counted. While we didn't pick the Simak for a Galactic Star last year, it's not a bad book, certainly better than the Heinlein and the Herbert, probably better than the Norton. I suspect the reason the Vonnegut finished so low is that, as a mainstream book, fewer had read it. Or perhaps just because it was so weird.

Short Fiction

The No Truce with Kings by Poul Anderson (93 votes)

Nominees

We got all of these this year, too. The Anderson was our clear favorite, being the only one on the list to rate a Galactic Star. The rest are in the order we had rated them. Sadly, because this category encompasses so many stories, a great number got cheated out of recognition. Perhaps they will divide the categories by length in the future.

Best Dramatic Presentation

None this year — insufficient votes cast for any one title to create a proper ballot.

I bet this will change next year what with so many SF shows coming out this Fall season (Rose Benton has got an article coming out in two days on this very subject!)

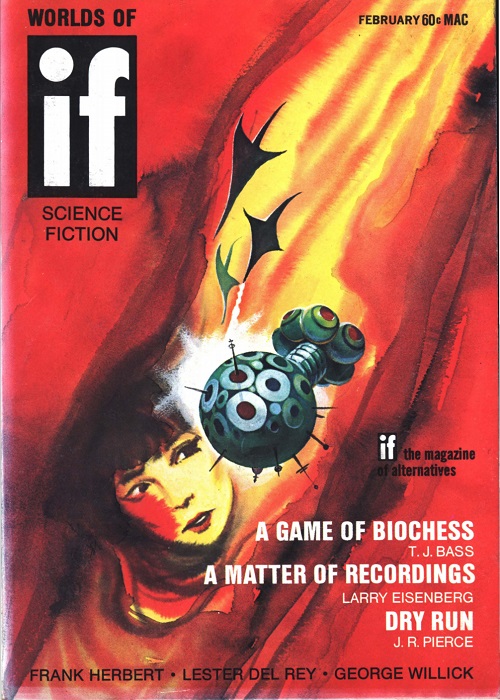

Best Professional Magazine

Analog ed. by John W. Campbell, Jr. (90 votes)

Nominees

It looks like people voted for the magazines in rough proportion to subscription rates, though F&SF did disproportionately well. I am happy to say that this is the year we start covering Science-Fantasy…in its new incarnation under the editorship of Kyril Bonfiglioli.

Best Professional Artist

Ed Emshwiller (77 votes)

Nominees

Book covers are showing their influence on the voting — Krenkel and Frazetta don't do the SF mags.

Best Fanzine

AMRA (72 votes)

Nominees

- Yandro (51 votes)

- Starspinkle (48 votes)

- ERB-dom (45 votes)

- No Vote (52 votes)

- No Award (6 votes)

(isn't it interesting how close the ERB fanzine's tally is to Savage Pellucidar's…)

I was glad to see that Warhoon, which is full-throatedly in favor of Walter Breen, was not in the running. Starspinkle, which makes no secret of its disdain for Breen, is the only one of these I read regularly.

Also, while Galactic Journey was not on the ballot again (for some reason), we did get a whopping 88 write-in votes. So, unofficially, we are the best fanzine for 1964. Go us!

Best Publisher

Ace Books (89 votes)

Nominees

- Pyramid (79 votes)

- Ballantine (45 votes)

- Doubleday (35 votes)

- No Vote (25 votes)

- No Award (11 votes)

I should keep track of who is publishing what for next year. The problem is, I usually read novels in serial format.

And that's it for my Hugos report. It'll be interesting to see if fandom's scars heal at all by next year.

Veterans of Foreign Wars

Given the turmoil in the papers and in fandom, it's not surprising that war is a common theme in science fiction, too. In fact, the October 1964 issue of Galaxy is bookended by novellas on the subject; together they take up more than half the book. They also are the best parts.

by George Schelling

Soldier, Ask Not, by Gordon R. Dickson

Centuries from now, after humanity has scattered amongst a dozen or more stars, the species has splintered to specialize in particular traits. The eggheads of Newton focus on scientific advance while the Cassidans make the building of starships their trade. The mystical Exotics have devoted their lives to nonviolent pursuit of philosophy. The Dorsai, of course, are renowned galaxy-wide for their military prowess. And the hyper-religious "Friendlies" are committed to faith.

Our story's setting is the wartorn Exotic world of St. Marie, where Dorsai mercenaries have been employed to topple the Friendly mercenaries who had conquered the world years prior. Newsman Tam Olyn has learned that the Friendlies' mission is a forlorn one, and he hopes to leverage that information to force the Christian zealots to do something desperate, illegal, to win the fight. For Olyn has a grudge to settle with the Friendlies, having watched them slaughter without mercy an entire company of surrendered soldiers several years back.

by Gray Morrow

Set in the same universe as Dickson's prior Dorsai stories, Soldier is a more mature piece, asking a lot of hard questions. Is Olyn's zeal any less than that of the Friendlies, any more laudable? If Olyn's actions cause the destruction of an entire sub-branch of humanity, can the species' collective psyche withstand the loss of one of its vital components?

Of course, the situation turns out to be far more complex than Olyn thought, with the Friendly commandant and the Dorsai commander proving to be independent variables beyond his control. In the end, nothing goes as planned.

Soldier is not perfect. It's overwritten in places, although since the tale is a first-person account written by a war correspondent, I wonder if this was intentional. The omniscience of the Exotic, Padma, who has an understanding of events and factors that would make even Hari Seldon jealous, is a bit convenient as a storytelling device. The idea that humanity has evolved in a few centuries, not just societally but mentally, such that vital components of our minds have been bred out of existence, is difficult to swallow.

But Dickson is a good writer, and I found myself turning the pages with avid interest.

Four stars.

Martian Play Song, by John Burress

A variation of patty-cake that will make you chortle. Three stars.

Be of Good Cheer, by Fritz Leiber

The first of two robot stories, this is a letter from Josh B. Smiley, Director-in-Chief of Level 77's Bureau of Public Morale to one Hermione Fennerghast of Santa Barbara. It seems she just can't be happy living in a mechanically run world, where robots ignore the people, where people seem to be increasingly scarce, and where both the indoors and outdoors are being reduced to dull grayness. Smiley does his best to reassure her that all is for the best, but the Director's verbal smile increasingly comes off as forced.

It's cute while it lasts, forgettable when it's over. Three stars.

The Area of "Accessible Space">, by Willy Ley

Mr. Ley offers us a list of near-Earth celestial targets that could be reached in the near future by rockets and probes. The author is quite optimistic about our prospect, in fact: "There can hardly be any doubt that a mission to a comet (unmanned) will be flown before a man lands on the moon."

Anyone want to lay odds?

Three stars.

How the Old World Died, by Harry Harrison

Robot story #2: computerized automata are programmed with one overriding desire — to reproduce. Soon, they take over the entire world, having deconstructed our buildings and machines to make more of them.

The twist ending to the story is not only ridiculous, but it also is in direct contradiction to events described earlier. Sure, perhaps the narrator (a crotchety grandpa who remembers the good old days) is not reliable. But if that be true, then 90% of the story is invalid, and what was the point of reading it?

Two stars.

The 1980 President, by Miriam Allen deFord

by Hector Castellon

Have you noticed that every President of the United States elected in a year ending in zero ultimately dies in office? Perhaps that's why, in 1980, the two big parties have nominated candidates they wouldn't mind losing (though they'd never admit it publicly).

A cute idea for a gag story, I guess. Except, in this case, the parties have been maneuvered into their actions by alien agent, The Brown Man, and his goal is racial harmony and equality.

Yeah, I found the whole thing a bit too heavy-handed for my tastes, too. I've liked deFord a lot, but her work lately has seemed kind of primitive, more at home in a less refined era of science fiction.

Three stars, barely.

The Tactful Saboteur, by Frank Herbert

by Jack Gaughan

From bad to worse. This unreadable piece involves a government with a built in Department of Sabotage to ensure things don't run too smoothly. I guess. Maybe you'll get more out of it than I did.

One star.

What's the Name of That Town?, by R. A. Lafferty

A supercomputer is tasked with discovering an event not from the evidence for its existence, but from the conspicuous lack of evidence. Lafferty's piece is an inverse of deFord's — a great idea rather wasted on a feeble laugh.

Another barely three-star story.

Maxwell's Monkey, by Edgar Pangborn

What if the monkey on your back was a real monkey? This monkey is a clunker.

Two stars.

Precious Artifact, by Philip K. Dick

Humanity emerges victorious from a war with the "proxmen", and Milt Biskle, a terraformer on Mars, is granted the right to return to Earth. He does so only reluctantly, subconsciously dreading a trip to his overcrowded homeworld.

Once there, he is wracked with fears that the teeming masses of people, the burgeoning skylines are all imaginary. Underneath, he is certain, lies nothing but ruins, smashed by the proxmen — who were actually triumphant and project this illusion to keep the few remaining humans sane.

But there is a level of truth even deeper…

A minor effort from a major author, Dick's latest warrants three stars.

The Children of Night, by Frederik Pohl

by Virgil Finlay

Lastly, Galaxy's editor picks up the pen to deliver a tale of marketing in the early 21st Century. It's a topic near and dear to Pohl's heart, he having started out as a pretty successful copywriter, and it's no surprise that he often returns to this subject in his stories.

In this particular case, Pohl's protagonist is "Gunner", a fixer for the world's most reputable (and infamous) publicity firm. They're the kind who'd even try to reform Hitler's image if the were enough Deutschmarks in the deal. And in 2022, Moultrie & Bigelow's client is no less than the Arcturan insectoids who tried to wipe out humanity in a decade-long interstellar war. I mean, how do you sell the public on a bunch of stinky bugs who killed indiscriminately and conducted experiments on children that would make Mengele blanch? (Who am I kidding — the bastard would take notes.)

Unlike many of the author's other marketing stories, this one is played straight; and while I don't know that I buy the ending, no one would argue that Fred Pohl can't write.

Four stars.

Picking up the Pieces

At times, the latest issue of Galaxy feels like a battlefield, with definite winners and losers. In the end, though, this kind of war is a lot more palatable than the other ones going on in the world.

At four bits, that's affordable and welcome R&R.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

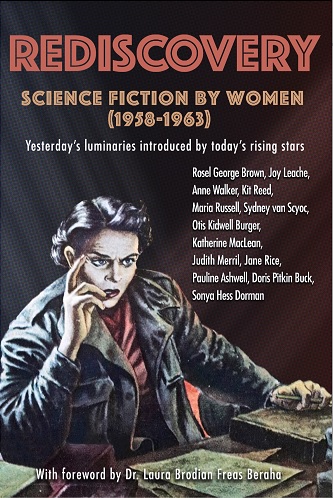

Wire photo of the aftermath.

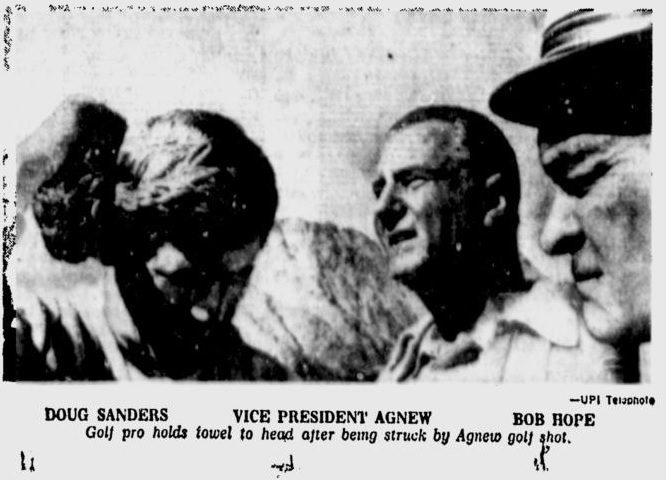

Wire photo of the aftermath. Arrival at Ocean-Deep. Art for “Waterclap” by Gaughan

Arrival at Ocean-Deep. Art for “Waterclap” by Gaughan

![[March 2, 1970] Par for the course (April 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IF-1970-04-Cover-476x372.jpg)

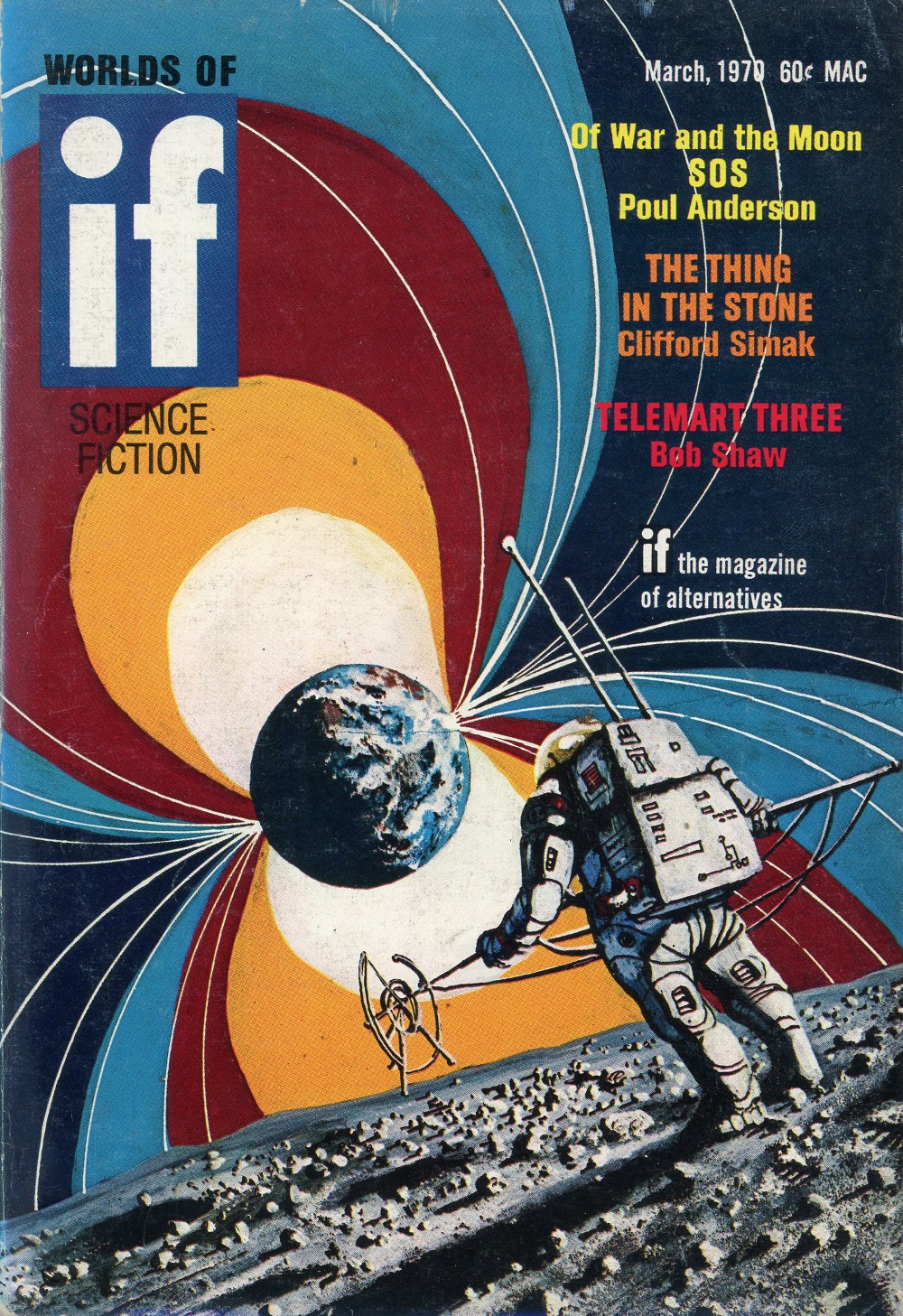

![[February 2, 1970] Deceptive Appearances (March 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/IF-1970-03-Cover-479x372.jpg)

The arbiter, an NCR 315.

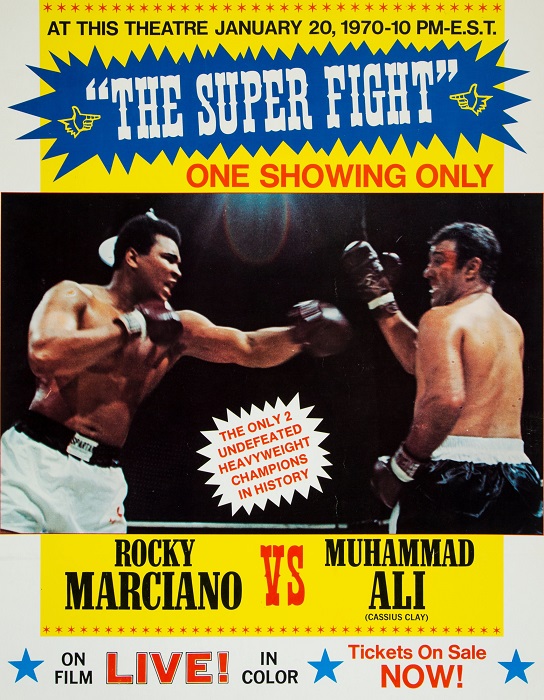

The arbiter, an NCR 315. Movie poster for the event. That “LIVE!” is a little deceptive, which is something else Ali is complaining about.

Movie poster for the event. That “LIVE!” is a little deceptive, which is something else Ali is complaining about. Art actually for “SOS,” rather than just suggested by. Maybe because it’s by Mike Gilbert, not the overworked Jack Gaughan.

Art actually for “SOS,” rather than just suggested by. Maybe because it’s by Mike Gilbert, not the overworked Jack Gaughan.![[January 2, 1970] Under Pressure (February 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IF-1970-02-Cover-500x372.jpg)

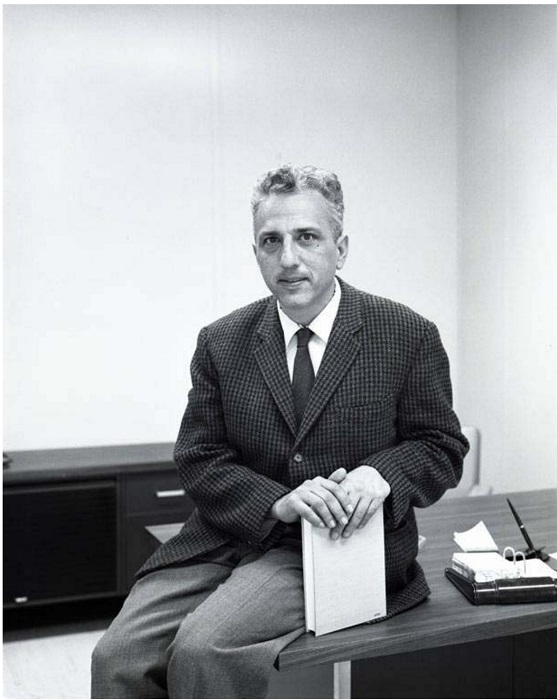

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California

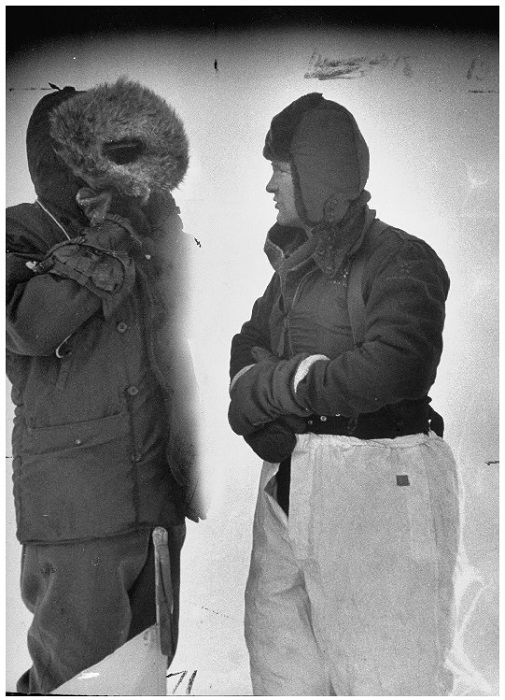

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find.

Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find. Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado

Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.

Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.![[December 2, 1969] Communication Breakdown (January 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/IF-1970-01-Cover-478x372.jpg)

Vice President Spiro Agnew addressing the Midwest Regional Republican Committee.

Vice President Spiro Agnew addressing the Midwest Regional Republican Committee. White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler

White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler![[September 8, 1964] It's War! (The October 1964 <i>Galaxy</i> and the 1964 Hugos)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/640908cover-672x372.jpg)