by Gideon Marcus

Making it

Many people harbor a desire for fame — their face on the screen, their star on a boulevard, their name in print. That's why it's been so gratifying to have been given plaudits by no less a personage than Rod Serling, as well as the folks who vote for the Hugos.

But it wasn't until this month that one of us finally made the big time. Check out this month's issue of Analog, for in the very back is a letter whose sardonic commentary makes the author evident even before one gets to the byline. Yes, it's our very own John Boston, Traveler extraordinaire.

Bravo, Mr. Boston. You've got a bright future.

As for Analog… there the outlook isn't so clear.

The Issue at Hand

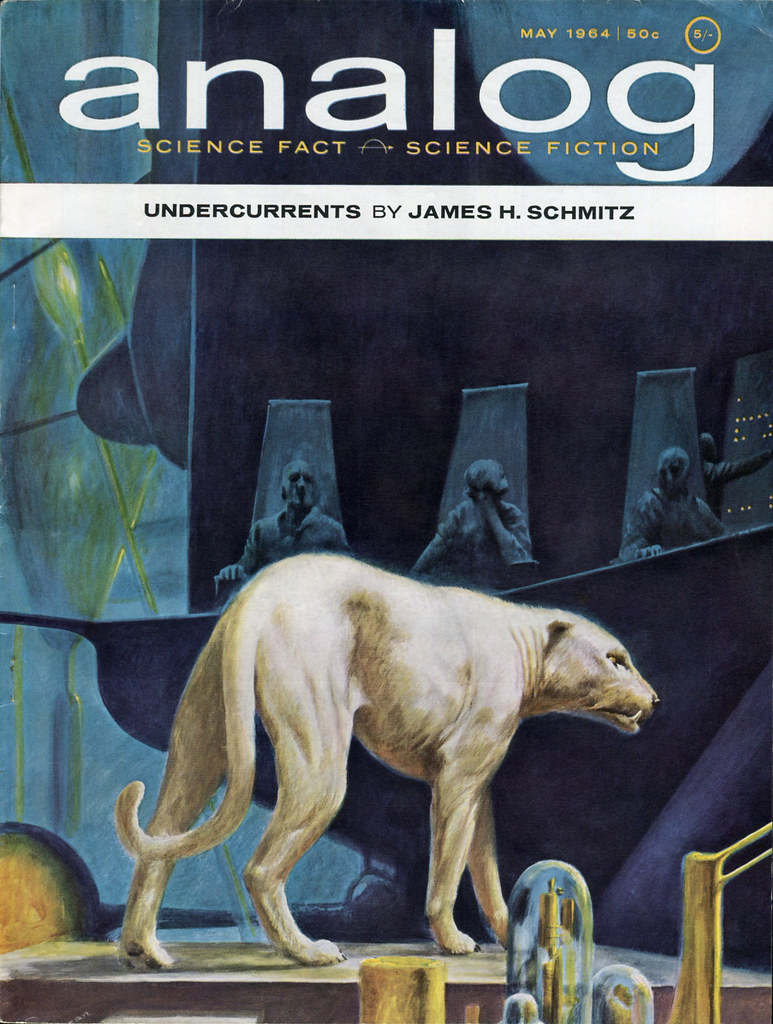

Cover by John Schoenherr

The Problem of the Gyroscopic Earth, by Capt. J. P. Kirton

Captain Kirton's treatise on the link between the galactic magnetic field and Earth's precessions is both unreadable and ludicrous. Basically (he argues), as the axis wobbles, pointing the poles at different sections of the sky in a many thousand-year cycle, the Milky Way works its voodoo and causes mass extinctions.

Pretty pictures are included, but I believe Kirton was indulging in some of Dr. Leary's happy juice when he wrote this.

One star (and only because the scale doesn't go any lower).

Undercurrents (Part 1 of 2), by James H. Schmitz

by John Schoenherr

Two years ago, James Schmitz introduced us to Telzey Amberdon, a 15 year old girl whose telepathic abilities allow her to establish the sentience of an alien species. It was sort of like Piper's Little Fuzzy, and while it wasn't the most adeptly written piece, the premise and the protagonist were so intriguing that I wanted to see more stories about them.

The good news is that I got another story. The bad news is that it isn't very good.

In this installment, Telzey goes off to the planet of Orado for advanced schooling at Penhanron College, along with Gonwil Lodis, an older girl on the threshold of adulthood and heir to a vast fortune. When Telzey makes telepathic contact with Gonwil's fierce canine bodyguard, Chomir, she learns of a plot to murder Gonwil, but the details remain frustratingly out of reach. Telzey must use her wits and her ever increasing talent to find the would-be assassins before they complete their mission.

It sounds pretty fantastic when written like this and, condensed down to its bare essentials, Undercurrents could be a great story. But the thing is padded to oblivion with pointless exposition, with whole pages of content that get explained again in a few paragraphs later on anyway. Moreover, I'm pretty sure that the dog is the lynchpin to the crime — I'll wager that in the conclusion, Chomir will turn out to have some sort of conditioning to turn on his owner.

I'll keep reading because I love the character, and I appreciate that there are a plethora of interesting women in Schmitz's world, but this could have been so much better in the hands of a more skilled (or interested?) writer.

Two stars.

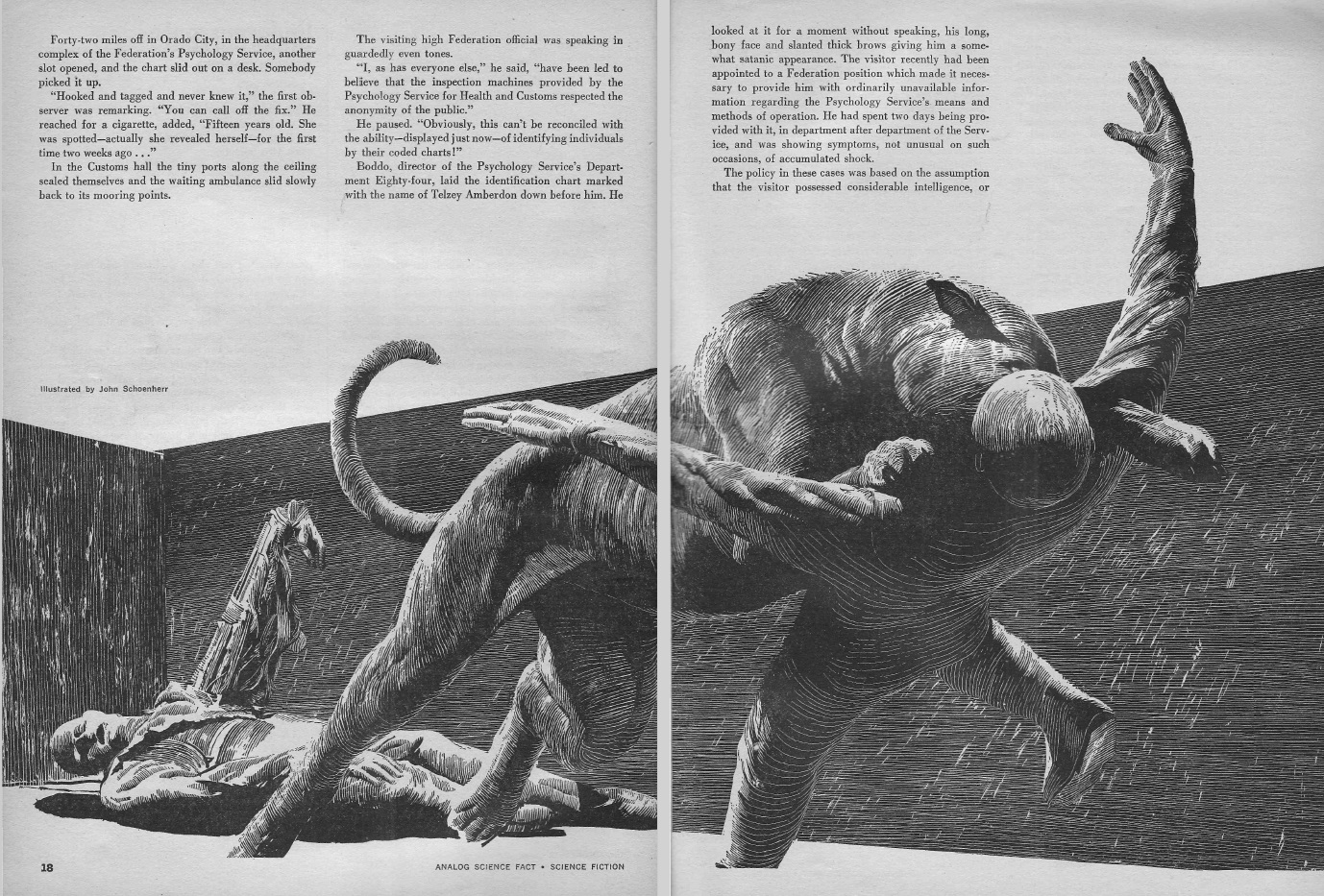

Fair Warning, by John Brunner

by Michael Arndt

On a Pacific atoll, moments before the atom bomb's big brother is about to be set off, a supernatural being manifests to adjust the device's detonator and ensure that it can go off properly. There's a Mene, Mene, Tekel, Parsin air about the event, but delivered with a sly smile. Horrified, the scientists get drunk and smash their equipment.

It wasn't badly written, but I found it kind of pointless. Two stars.

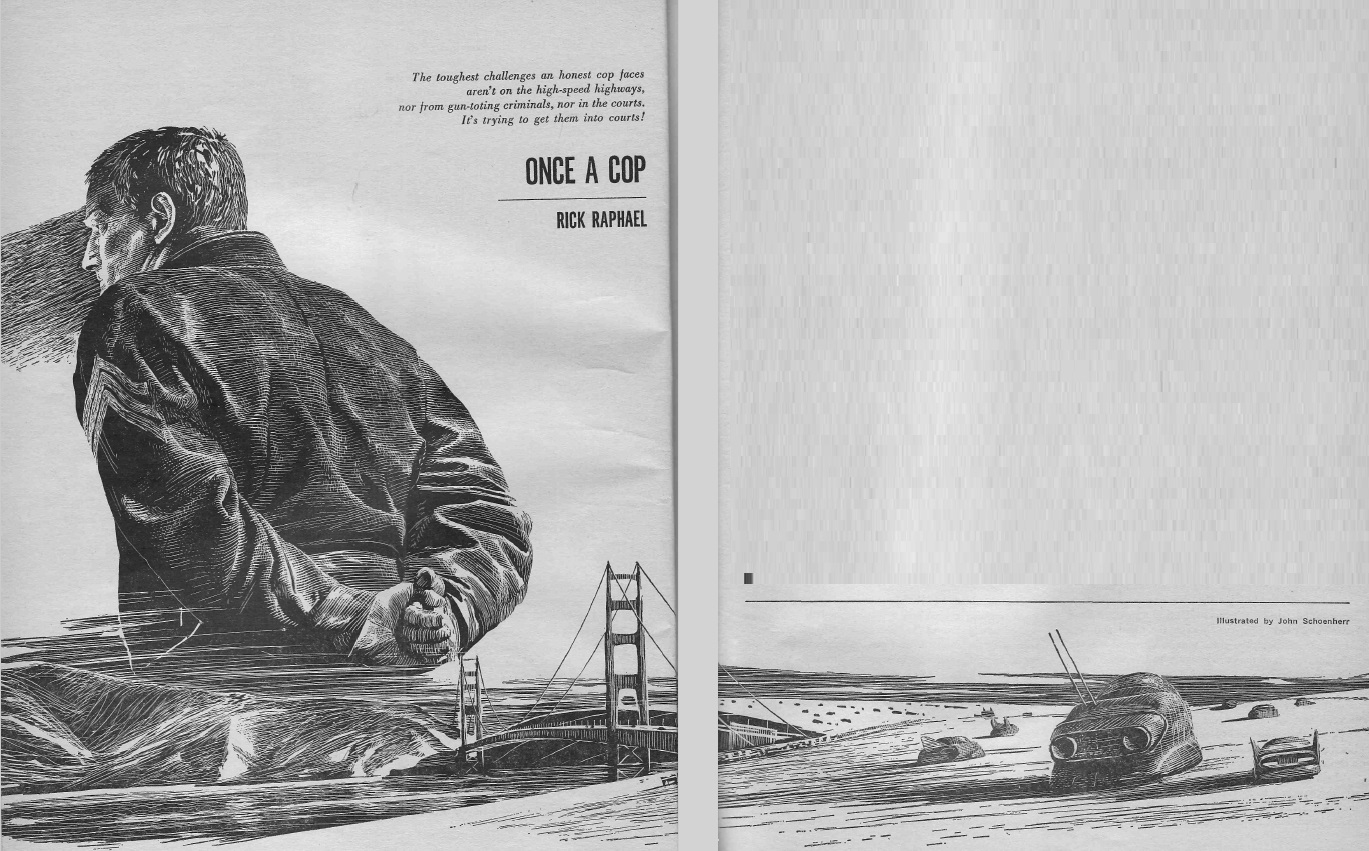

Once a Cop, by Rick Raphael

by John Schoenherr

This is the second installment in Raphael's "Code Three" universe, featuring a future where the North American continent is crisscrossed by mile-wide freeways. Cars hurtle from town to town at speeds over 200 mph, and the job of the Highway Patrolman is more necessary — and dangerous — than ever.

Once again, we follow the exploits of the seasoned Sergeant Ben Martin, rookie Clay Ferguson, and surgeon Kelly Lightfood, crew of "Beulah", a 60-foot patrol behemoth. The piece depicts a number of crises, from a drunk speedster who soars off a highway curve, to a trucker who gets lost in a sandstorm, but the main arc involves a spoiled rich kid who is taken into custody after zooming through a closed lane and almost plowing into an accident scene. Said kid's father is a big wheel in corporate America, and he tries everything from bribery to blackmail to get his son out of trouble.

I hadn't expected to like this series so much, but Rafael does an excellent job of presenting the technical aspects of the story smoothly, and all of the vignettes are exciting. It reads less like a cop show (viz. the TV show Highway Patrol) and more like a series on firefighters. Plus, I dig that there is a prominent and tough woman in the crew.

Four stars, and keep 'em coming.

A Niche in Time, by William F. Temple

by Laszlo Kubinyi

Artists are a moody bunch, and apparently, most of the greats had profound moments of doubt that almost stymied their careers. It turns out that, for many of them, the difference between throwing in the towel and going on to make masterpieces is an organization of time travelers. They appear on the doorstep of the depressed creators and take them to the future to see the laurels of success. Then the artists' memories are wiped, but the impetus remains.

No, it doesn't make a lot of sense, and this story would veer strongly into two-star territory if not for the final twist. And, while the premise is hard to swallow, it is consistent unto itself.

Three stars.

Hunger, by Christopher Anvil

by Laszlo Kubinyi

Last up, we get a look at a failing settlement on a colony planet, whose inhabitants have been laid low by disease and mechanical failures such that just two men and a baby remain. Their only hope is the sack of potatoes one of the fellows has managed to obtain from another straggling settlement.

The fortunes of the three are made all the worse when a pleasure yacht arrives from Earth and proceeds to set the forest afire with negligent aplomb. The two colonists are left with but one option: use their resourcefulness to capture the yacht and make the jerks stop their wanton destruction.

This story was almost quite good. The setup was interesting and I like a story that starts with one problem and then brings in another out of left field. What keeps the piece solidly in the three-star range is the page of moralization at the end, in which a character opines that it's struggle that makes happiness possible, but then takes things too far by saying, "Back home, they're always talking about abolishing hunger. They might think about it some more." Plus, there's just some awkwardness and nastiness about the ending, and the suggestion of women as prizes that rubbed me the wrong way.

So, three stars. Maybe it was better before Editor Campbell got his paws on it.

Summing up

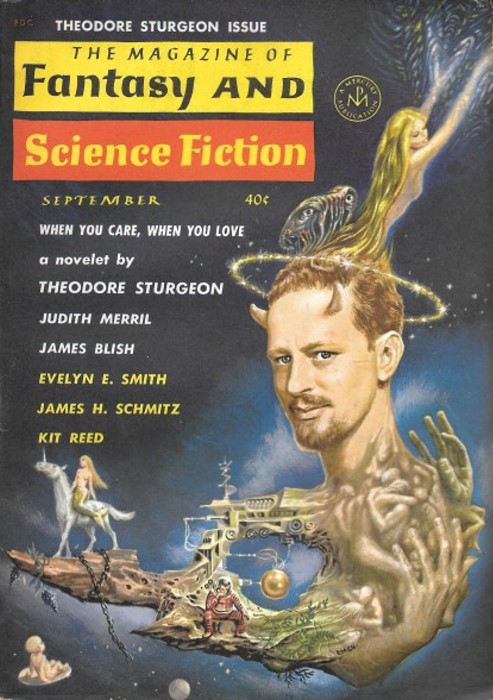

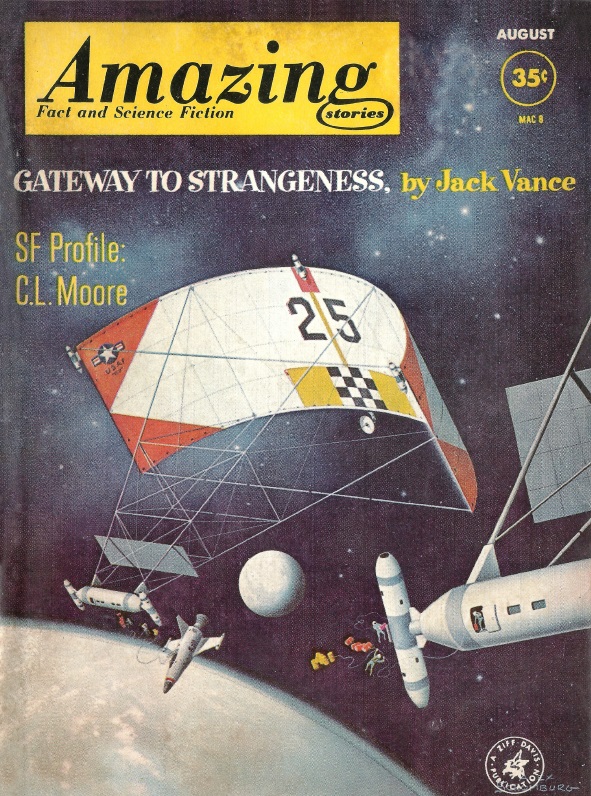

April is done, so let's close the books and do the numbers! Starting from the bottom, we have Amazing, managing to earn just two stars. Some folks liked the Smith and Brown better than John Boston, but in general, it was a stinker. That's a shame since it may be the only magazine to date with more words penned by women than by men. The Analog we just got through, Boston letter notwithstanding, gets 2.6 stars. Meanwhile F&SF earns an uninspiring 2.7 stars, but it did feature good stories by Clingerman and Carr (and if you like Ballard, by him, too). Finally, Fantastic gets 2.9 stars, but if you're a Leiber and/or Moorcock fan, it might earn more from you.

This leaves three mags at three stars or higher, which is pretty good, actually. IF gets exactly three, with the Cordwainer Smith story making it a worthy acquisition. Worlds of Tomorrow has got some great stuff in it, even a good Jack Sharkey tale fer Chrissakes, and scores 3.3. And the new New Worlds gets a respectable 3.4.

Women wrote 4 of the 43 new fiction pieces this month. And despite the somewhat low showings of a lot of the mags, there were more standout tales this month than most.

Onward to June!

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[May 2, 1964] The Big Time (May 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640502cover-672x372.jpg)