by Fiona Moore

With so little decent science fiction and fantasy film available this year, I’m back at the second-run cinemas again, catching up on movies I missed the first time round. Bedazzled is a modern take on the legend of Faust in the inimitable style of Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, accompanied by Eleanor Bron as an up-to-date Gretchen who doesn’t sit around pining at the spinning wheel. It’s got a couple of nice psychological character studies at its heart and a few wry things to say about human nature, though coming to an optimistic conclusion on the subject.

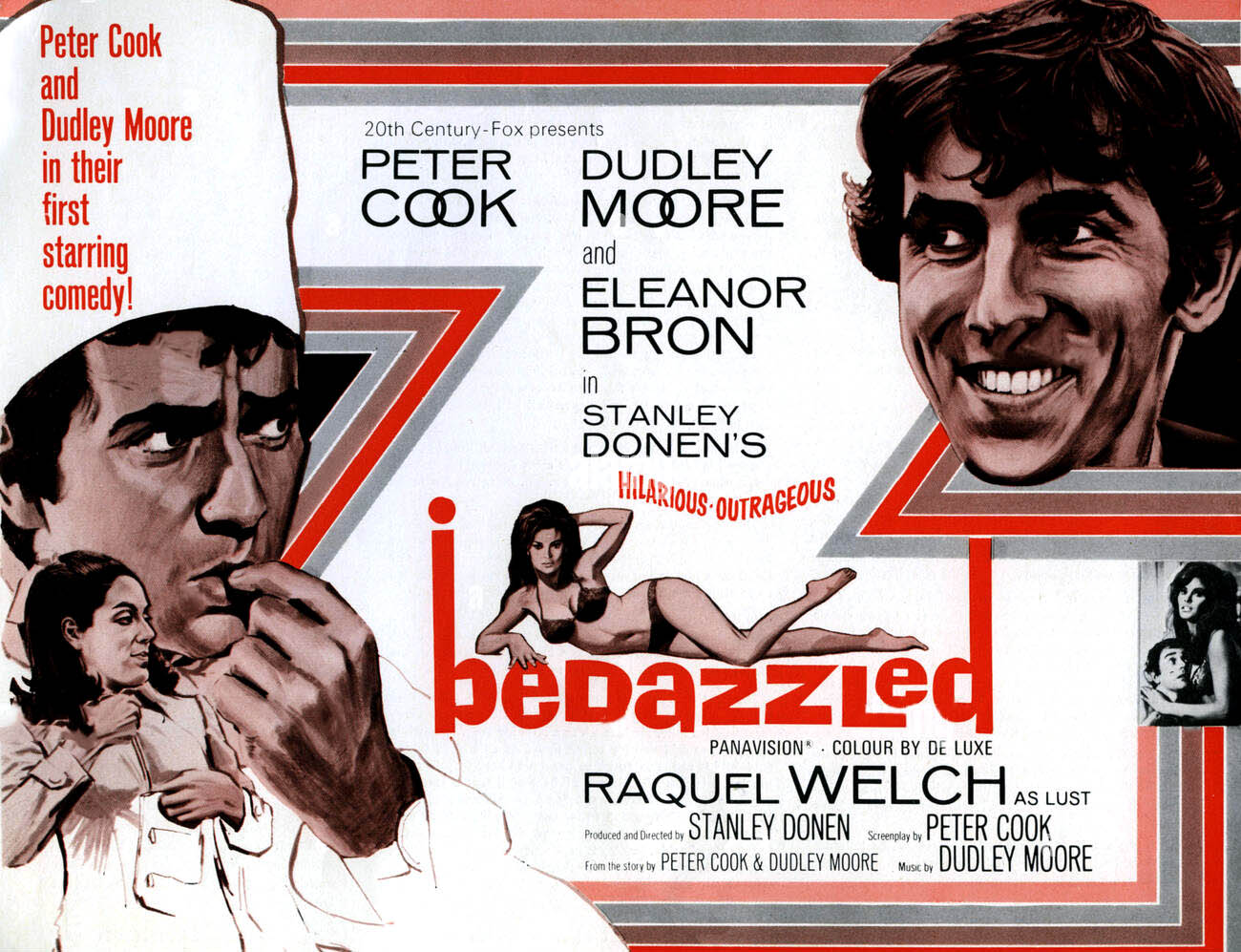

Original movie poster for "Bedazzled"

Moore plays Stanley Moon, working as a cook in a Wimpy Bar and living in a grotty London bedsit, consumed with desire for his coworker Margaret (Eleanor Bron) but unable to work up the courage to ask her out. This makes him easy prey for Satan, aka “George”, played by Peter Cook, turning up initially in a stylish black and red cloak, little sunglasses and velvet dinner jacket.

After Stanley has signed away his soul in exchange for seven wishes, the rest of the movie is mostly sketches in which Stanley’s wish comes true—he is a witty intellectual, a millionaire, a pop star, a fly on a wall, and other things—and yet he fails to win Margaret. These are interspersed with more metatextual sketches in which George goes about his business of spreading unhappiness and misery in petty but effective ways (sending pigeons out to defecate on pedestrians; issuing parking tickets; conning little old ladies; scratching LPs) while Stanley trails after him, complaining, but finding it hard to take the moral high ground. Over the course of the story Stanley gradually comes to realise some things about himself, Margaret, and George, and, without revealing the ending, it’s fair to say that he comes out of the experience a better man than he went in.

Stan, about to strike out with Margaret again

Stan, about to strike out with Margaret again

Like Oh! What a Lovely War, this is a movie which makes a virtue of a low budget. It’s shot around London but with a sometimes witty and surreal choice of locations: the Devil’s headquarters is a cheap nightclub, Heaven is the Glass House at Kew Gardens, George at one point takes Stanley up to the top of the Post Office Tower in a visual joke about the Devil showing Christ the kingdoms of the world. Modern takes on the Seven Deadly Sins all turn up, with Raquel Welch typecast as Lust (and we learn she’s married to Sloth), and Vanity represented by a man with a mirror physically growing out of his chest. There’s a delightful parody of pop hits programme Ready, Steady, Go!, and there are clever little touches like a record scratched by George in one sketch putting Stan off his game with Margaret in another, or a headline, “Pop Stars in Sex and Drugs Drama”, shifting by one letter to become “Pope Stars in Sex and Drugs Drama”.

Within all of this, though, there are running themes about human nature and our ability to make ourselves contented or miserable. Stan, at one point, rails at George, “you promised to make me happy!” and George counters, “no, I promised to give you wishes.” Throughout the sketches, Stan keeps screwing things up with Margaret not through George’s intervention but through his own personal failings: as an intellectual, he completely misreads her willingness to sleep with him; as a millionaire, he keeps giving Margaret expensive gifts but no personal attention. He never fights to win her away from his rivals; he never takes an interest in her as a person. He whines that freedom of choice is all a lie, citing the fact that he had no choice where he was born, or to whom, but it’s obvious the problem is less Stan’s lack of opportunities, and more his inability to take advantage of the opportunities he has. It’s only when he recognises that being himself is better than the alternatives, that he can finally escape George’s grasp.

The Top of the Pops parody is spot on.

The Top of the Pops parody is spot on.

But, as the film continues, we also get a sadder insight into Stan and George and why they are the way they are. Stan tells George that George is the only person who has ever taken an interest in him, or done anything nice for him, showing how people can fall into temptation and sin not through moral depravity, but simple loneliness. George, for his part, eventually shows his own vulnerability: he is bitterly envious of God and wishes he could once again be among the angels, but at the same time is unable to rise above petty game-playing and point-scoring and can never understand why Heaven is closed to him. There’s also a running critique of modern life, with the Devil being associated with things like parking meters and tedious slogans like “Go To Work On An Egg”. Peter Cook gets in a rant about the evil of the banality of Wimpy Bars and Tastee Freezes and advertising and concrete, whose sentiment at least recalls Tati’s visual skewering of the sameness of global cities in Playtime.

Sermon on the postbox

Sermon on the postbox

All that having been said, it’s not a perfect movie. The metatextual sketches tend to go on a bit too long, and, although the message of the film is in part that Stan needs to stop viewing Margaret as a prize to be won and instead let her be her own person, we don’t really get much of a sense of her except as a prize to be won. The message—appreciate what you’ve got and don’t go looking for more—also doesn’t feel very aspirational. I suspect that if you don’t happen to like the humour of Peter Cook and Dudley Moore more generally, you’ll find the movie offputting. If you do like them, though, check Bedazzled out when it shows near you.

Four stars.

![[November 4, 1969] A Dazzler (Bedazzled, 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691104bedazzledposter-672x372.jpg)

![[January 12, 1969] Taking French Leave: Playtime (a movie) and The Green Slime (a flick)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/690112movies-672x328.jpg)

The car carousel makes Paris playful again

The car carousel makes Paris playful again