by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

With so much news about social reforms or issues in Rhodesia and Aden, it is easy to forget that the economy was one of the main issues that led to Wilson’s election as Prime Minister, in particular dealing with the trade deficit.

For almost a decade now Britain has been importing more than it has been exporting. With this many British consumers are choosing foreign made goods over domestic ones causing problems for local industry, not a good look for a country that was once dubbed “The Workshop of the World.”

The reasons for this date back a long way. From early adoption of manufacturing and overreliance on imperial exploitation, to the spending of Post-War American aid on military ventures (instead of the intended economic strengthening). However, one of the biggest is the value of the pound.

Whilst other countries trying to recover after the Second World War, such as Japan, had their currency set low, Britain strived to keep its value high. It has even become a point of national pride to have the Sterling as a major player in international trade, and devaluing had been something that had to be avoided at all costs.

However, world events have continued to put trade and the currency under strain. With the Arab-Israeli war, the fighting in Aden and failure to join the EEC, it was seen by Wilson as a necessary act. Whilst the economic impact will likely come later, the political impact has already been major. The chancellor, Jim Callaghan, has resigned and there have been attacks from all ends of the political spectrum that this is a breach of trust.

As I read this month’s stories in the anthology "New Writings in SF 11" and magazine "Beyond Infinity", I could not help but wonder if there was some devaluation going on here as well. The quality I was getting for my money seemed to decline as I read on:

Dobson’s hardback release was delayed, meaning we get the Corgi paperback (and their much prettier cover) first this time.

In another change the theme here is much broader, with imaginative looks at humanity’s future.

The Wall to End the World by Vincent King

Following his brilliant Defence Mechanism, Vincent King gives us another spectacular tale. Five thousand years earlier, the ancients built the Wall, a thousand-mile circle to protect the ordinary people in the City and the Teachers in their Citadel. Our narrator is an officer of the Wall, determined to protect it from all invaders. When he discovers the return of the ancient ones and the appearance of a new star in the sky, he knows the prophecy of the end is coming true.

In a beautiful and cleverly written 25 pages, King gives a deeper more complex world brimming with science fictional concepts than most writers manage in an entire novel series. There is fascinating mix of old & new technologies, with looking screens and robots mentioned in the same breath as horses and crossbows. But it is never ponderous or boring. Throughout it races along like the best adventure stories.

Five stars, only because I can’t give it a sixth!

Catharsis by John Rackham

Professor Caine is on the verge of a major breakthrough in particle physics, when he starts getting terrible headaches. After he checks into Dr. Halleweg’s clinic he discovers he only has 48 hours left to live.

A more experimental story than I would expect from Rackham with limited SFnal content. It is solid but feels like it is aiming for the current New Worlds style without really getting there.

Three Stars

Shock Treatment by Lee Harding

Pietro struggles to keep his memories and personality intact as he searches for The Great Engine of the world.

This is the kind of slow atmospheric apocalypse that seemed to fill the British magazines after Aldiss’ Greybeard was published. Not bad but nothing new.

Three Stars

Bright Are the Stars That Shine, Dark Is the Sky by Dennis Etchison

Space travel has failed to provide a suitable home for humanity and has been abandoned. With Los Angeles’ population reaching twenty million the old city is being torn down to provide enough housing for everyone. This vignette follows a young boy and an ex-spacer night watchman as they visit The Museum of Space Science and Technology before it is destroyed.

This is a lovely melancholy tale of the loss of innocence and the danger of losing hope in the future. Simple but memorable.

Four Stars

There Was This Fella… by Douglas R. Mason

Alf Pearson has a problem: he keeps jumping between planes of reality. His doctors think he is just highly suggestible, but what is real?

I felt this concept was already used to better effect in de Camp’s Wheels of If. I am not sure if I missed something important or if it was all just a bit hollow.

Two Stars

For What Purpose? by W. T. Webb

After an explosion at the Grenville Power Station, Tom Berkley finds himself in Marginburg: town like Grenville but tinged with bizarre touches, such as the sky being patched up with newspaper, an enormous house with no windows, and regular raids from pirates. How did he get here? And can he get back home?

This one is tough to know what to make of, because much of it has the surrealism of Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds and then it ends in a manner that could either be read as genius or nonsense. I will be generous and choose the former.

Four Stars (or Suit-of-Armour Newsprint in Marginburg).

Flight of a Plastic Bee by John Rankine

Paul Karadoc is sent to investigate Station K, repository of secure knowledge in orbit around planet Earth, populated by artificially prolonged humans known as Biomechs. Information has been leaking out of the station and it is up to Karadoc to discover how and why.

This is the second tale from Mr. Mason and an even weaker one, I found it dull and often incomprehensible. Even Doctor Who’s Cyberman adventures do a better job of exploring some of these themes.

One Star

Dead to the World by H. A. Hargreaves

I have been reliably informed this is the same Hargreaves who wrote Tee Vee Man 4 years ago, just with a different first initial, possibly a typographical error. Talking of mistakes, this is the story of Joe Schultz, a man accidentally declared dead in a future where administration is primarily run by computers.

This starts out as an interesting Kafkaesque tale, but soon descends into pure silliness.

Two Stars

The Helmet of Hades by Jack Wodhams

On the planet Albermarle, the inhabitants have been turned blind by the farmer Galig as part of a plot to rule over it as the only sighted adult. Marshal and Cresswell work to resist him.

Wodhams is not an author who has appeared in New Writings before but seems to have done quite well for himself writing mediocre tales for Campbell. Unfortunately, this is even more disappointing. It doesn’t seem to make a real attempt to understand blind people or communities, is overlong and the concept had a better treatment from Wells decades ago.

One Star

Beyond Infinity Dec. 1967

With the continued disappearance of SF magazines from the market and others turning to reprints, any time a new publication appears, I am keen to give this new magazine a try.

It opens with a strong editorial from Doug Stapleton, saying you will not see a “wild, Bondian adventure on the outer rim of the universe” within. Instead, he says, this is more devoted to “What-if-ness”, tales of the strange and uncanny.

Perhaps that is why they chose to print the contents in a randomised order?

Anyway, let’s explore these “other dimensions”:

Of Human Heritage by Wade Hampton

Years ago, a ship full of pioneers crashed onto an unknown planet and no Earth ships have found them. As the last of the original colonists, Old Pendennis, lies dying, he worries whether or not the future generations will be able to maintain their humanity.

This is not a bad tale. It is well written, with a nice narrative style and strong ending, but it also feels like a missed opportunity to me, as it could easily have explored some much deeper themes.

Three Stars

Communication Problem by John Christopher

In 2049 instantaneous warp travel between nearby stars has become safe and routine, that is unless you are travelling after Burns Night with a Scottish duty officer. When the Wayfarer lands inside a sub-electronic storm the ship is forced to crash on to a planet, the last survivor of the crew is rescued by The Mori, but why can the two species not communicate?

This feels like a story intended for Analog that was rejected. We have lots of dull explanations of engineering, aliens being baffled by humans, even mentions of ESP. I do get the sense from some of Christopher’s writing he isn’t all too keen on the other nations of The United Kingdom, and this tale is obviously no exception. Maybe the anti-Scottishness was too much for a Campbell?

One Star (and a big apology to my friends north of the border)

Whirligig! by John Brunner

Of late Brunner seems to be returning to some of his creations from the 50s. We recently got a serial set in his future Empire, and a sequel to Imprint of Chaos. Now it is the turn of his strange jazz troupe, Tommy Caxton and the Solid Six.

This gives us one side of a conversation, as Caxton tries to convince his record label to include Gumshoe Stumble as their next single.

Unfortunately, this is no Traveller in Black. Instead it is a series of run on sentences with barely any SFnal content (at least that I could understand). I know I am in no position to critique another’s grammar but I found it near unreadable. But it is also true that I don’t get jazz.

One Star

Talk to Me, Sweetheart by Ben Bova

Finishing the trilogy of big names, we get Bova giving us another space-flavoured tale. Here an astronaut in orbit is losing control and only the woman’s voice on the other end of the communicator can help him.

Basically this is the opening scene of A Matter of Life and Death transferred to space, albeit with a different ending, one most readers will see coming from eight miles high.

Two stars

5-4-3-2- by James McKimmey

Christopher Raamsgaard has been hit hard by the death of his business partner and has been working incredibly hard. Is this why he has started doing everything backwards? Or is something stranger going on?

Mr. McKimmey seems to be returning to SF, with two sales to Pohl’s magazines recently. However, just like those, this is not a good piece. Hoary, dull, silly, it would have been a space filler a decade ago.

One Star

The Deadly Image by McHugh Ferris

Emile Varner creates a robotic recreation of Lincoln and puts on a hugely successful show where people can experience his last night at Ford’s Theatre. But is history doomed to repeat itself?

Pointless piece of filler barely moving on from the current Mr. Lincoln Speaks attraction.

One Star

Revenge at the TV Corral! by J. de Jarnette Wilkes

Ken Dexter was the star of the major TV western, Western Marshal. Now he has been killed off and replaced by Bill Todd. When his wife also left him for Todd that was the last straw and he goes to murder them.

This is an odd story, that seems to be attempting some sort of post-modern narrative about the narrative itself, but never really works for me.

Two stars for effort.

The 13th Chair by Michael Quentin Lanz

Wes Pepper’s syndicated column is extremely popular but, with a huge libel suit against him and twelve deaths resulting from his distortion, his publisher want rid of him. But Mr. Pepper is not so easily got rid of.

A nasty story without much depth and the feel of Weird Tales.

Two Stars

Upon Reflection by Gilmore Barrington

Wilbur Trimble hates his wife and wants to kill her. Perhaps the Christian carnival that has come to town will provide an opportunity.

A bad horror story about a terrible man.

One star

Mommy, Mommy, You're a Robot by Dexter Carnes

Stevie Bellamy is an ordinary kid during the day, but at night he dreams of travelling from Omicron and that his mother is actually a robot. Do I even need to say where this is going? Unoriginal, poorly put together and speckled with random racist language.

One Star

Greetings, Friend! by Dorothy Stapleton and Douglas Stapleton

The Ecknode crashes on an unknown planet without any hope of escape. Suddenly he sees another craft come across the sky, is it his chance of escape?

It is ironic, given his introduction, that the editor gives us the most traditional science fiction story. Whilst not a “Bondian adventure” it is a dull old-fashioned first contact story that wouldn’t be out of place in '40s Astounding.

One Star

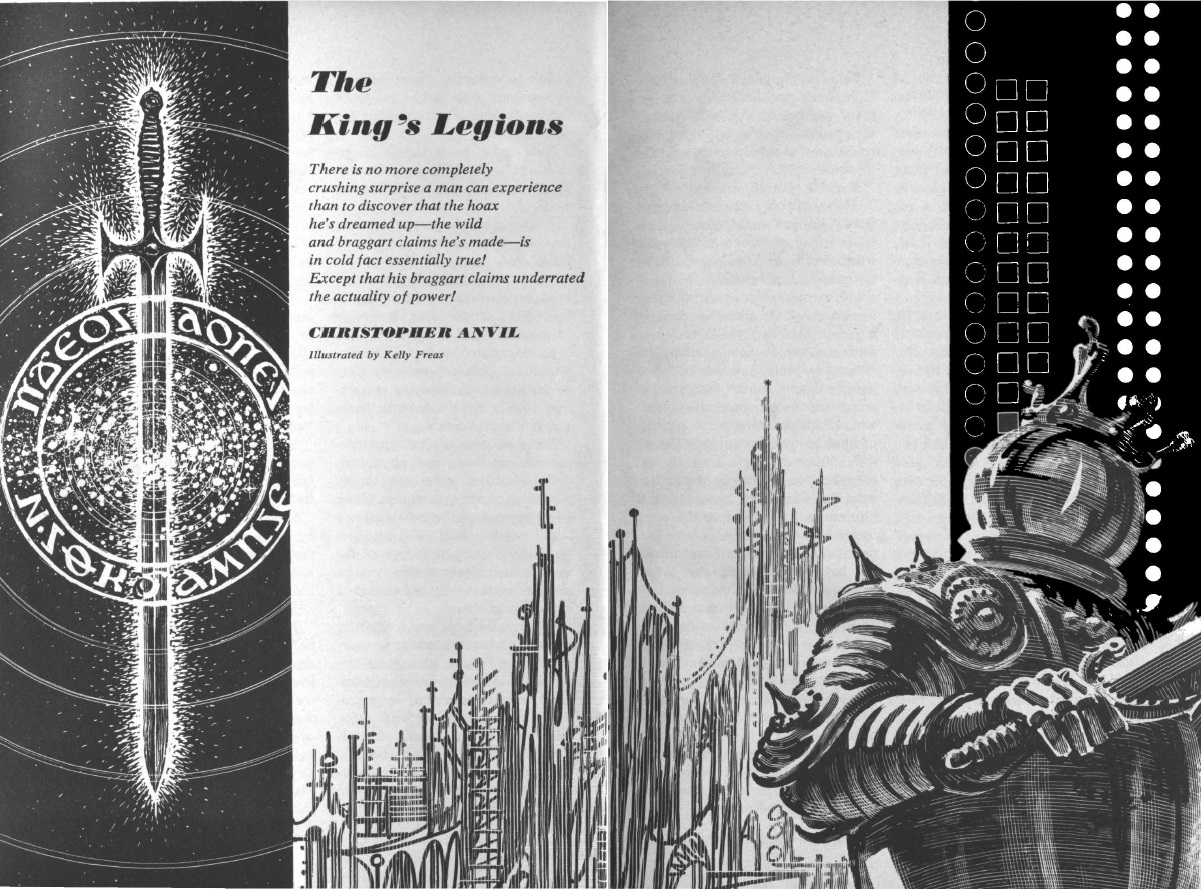

The New Way by Christopher Anvil

Burr Macon is Chief of Crime Documents, here helping deal with a prisoner who has confessed to murder. He gets to experience a new form of punishment and rehabilitation instead of the death penalty, reliving his victim’s experience.

If the last story felt like '40s Astounding, this was pure '50s Galaxy. Unfortunately, Anvil is not William Tenn or Robert Sheckley, and the whole thing feels rote. At least it is competent, which is more than I can say for most of this magazine.

Two Stars

The DNE?

Whilst there were some good stories at the start of New Writings and a reasonable one at the start of Beyond Infinity, there was a decline throughout. Hopefully this devaluation can stop and not continue into subsequent issues.

![[December 4, 1967] Devaluation (<i>New Writings in SF-11</i> & <i>Beyond Infinity</i> December 1967)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Cover-Image-672x372.jpg)

![[November 30, 1967] One door closes… (December 1967 <i>Analog</i> and Australia joins the Space Race!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/671130cover-672x372.jpg)

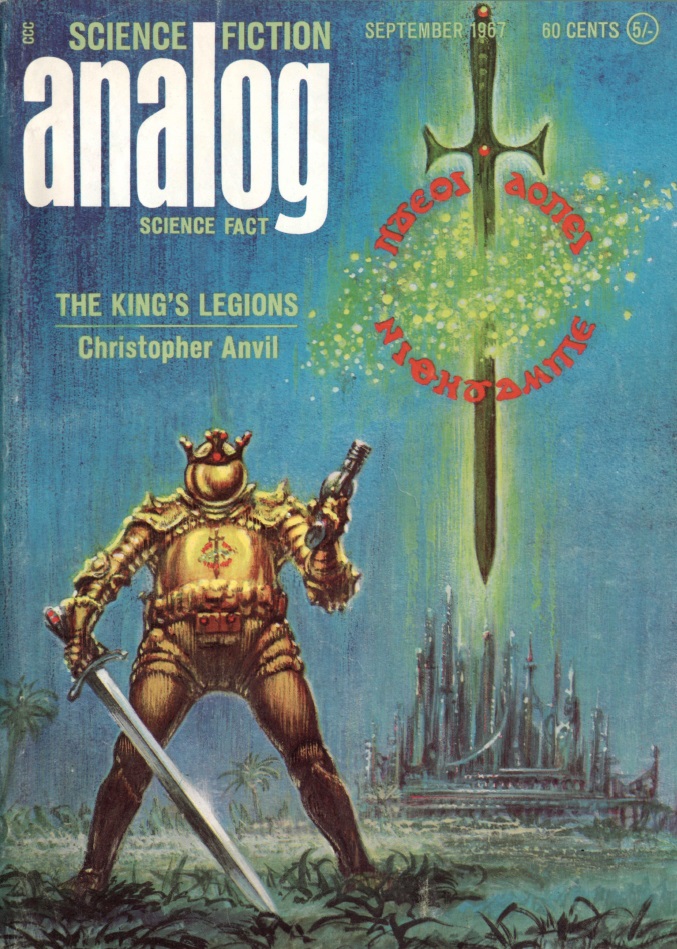

![[August 31, 1967] I wouldn't send a knight out on a dog like this… (September 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670831cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 31, 1967] The Law of Averages (February 1967 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/670131cover-672x372.jpg)