by David Levinson

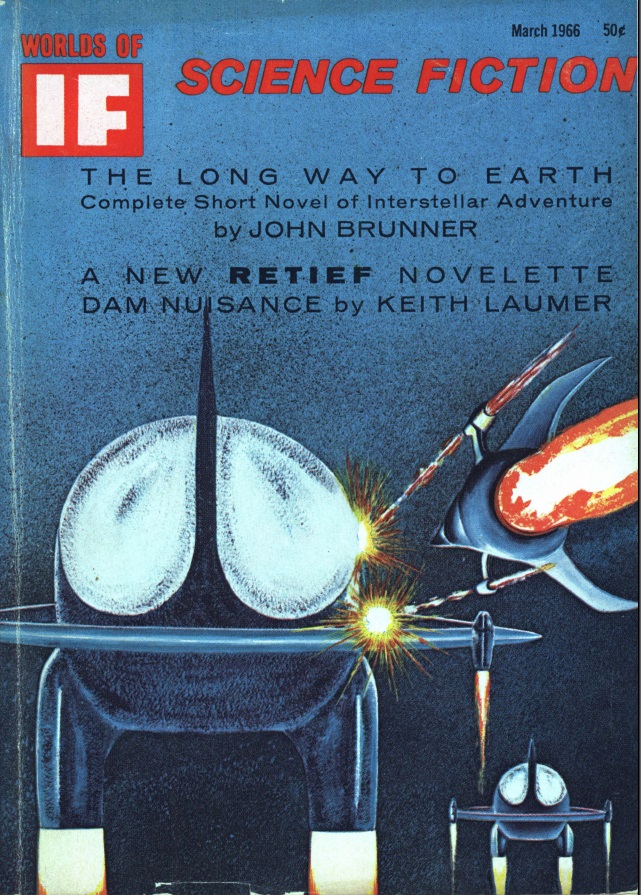

Autumn is a strange time for new beginnings, but that seems to be something of a theme, both in life and in the latest edition of IF.

Carnival atmospheres

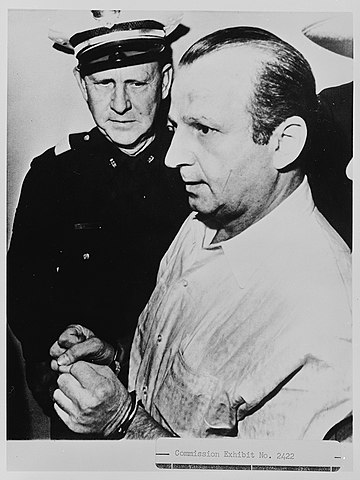

On October 5th, the highest appeals court in Texas ruled that Jack Ruby, the man who shot the man who shot President Kennedy, should be granted a new trial. The court said that, given the tremendous amount of publicity in Dallas about the shooting, the judge should have granted the request for a change of venue made by Ruby’s lawyer, Melvin Belli. The court also ruled that some statements made by Ruby to the police should have been excluded. Oddly, the court didn’t have a problem with people who watched the shooting on television being on the jury. The new trial will probably be the big news story early next year.

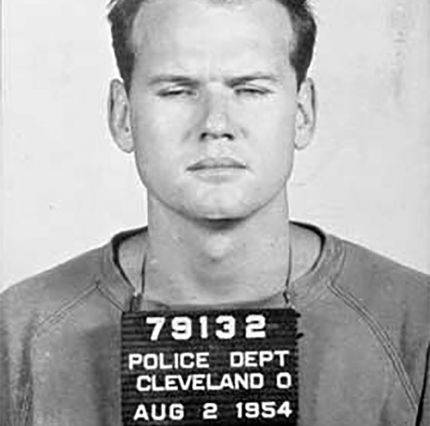

Jack Ruby shortly after his arrest.

The Texas court may have followed the Supreme Court ruling in Sheppard v. Maxwell back in June. In 1954, Dr. Sam Sheppard was convicted of the brutal murder of his wife Marilyn. He maintained that she was killed by a “bushy-haired” man, but he was tried and convicted in the press before he was even arrested. The story became a national sensation, and the jury was exposed to further declarations of Sheppard’s guilt in the press throughout the trial. Before the trial began, the judge even told Dorothy Kilgallen that Sheppard was obviously “guilty as hell.” Jury selection for a new trial began on October 24th, and the prosecution should have begun to present their case by the time you read this.

Sam Sheppard’s mug shot from 1954.

Rising from the ashes

In this month’s IF, it seems like almost everybody is starting over. Whether it’s their personal lives, civilization or the human race, they’re all trying to put things back together.

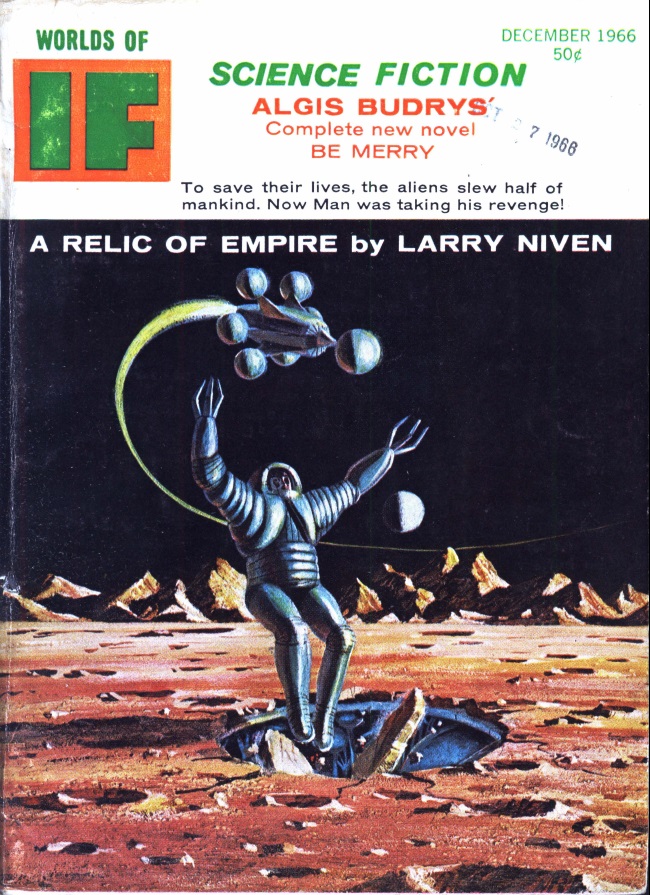

This doesn’t look like it has anything to do with the Niven story. And they got the title wrong. Art by Gaughan

Continue reading [November 6, 1966] Starting Over (December 1966 IF)

![[November 6, 1966] Starting Over (December 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/IF-1966-11-Cover-650x372.jpg)

![[October 2, 1966] At Heart (November 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/IF-1966-10-Cover-646x372.jpg)

![[September 2, 1966] On the Edge (October 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/IF-1966-10-Cover-662x372.jpg)

![[August 2, 1966] Mirages (September 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/IF-1966-09-Cover-654x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1966] The Big Thud (August 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/IF-1966-08-Cover-644x372.jpg)

![[June 2, 1966] Bad Decisions (July 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/IF-1966-07-Cover-654x372.jpg)

![[May 2, 1966] By Any Other Name (June 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/IF-1966-06-Cover-650x372.jpg)

![[April 2, 1966] Hidden Truths (May 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/IF-1966-05-Cover-659x372.jpg)

![[March 2, 1966] Words and Pictures (April 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IF-1966-03-Cover-1-657x372.jpg)

![[February 8, 1966] Feeling A Draft (March 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IF-1966-03-Cover-641x372.jpg)