If you are in the accounting profession, you are familiar with the concept of "closing the books," wherein you complete all your reconciliations and regard a month as finished. Here at the Journey, Month's End does not occur until the last science fiction digest is reviewed. Thus, though the bells have already rung for the new year of 1961, December 1960 will not officially end until I get a chance to tell you about the latest issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction!

It's an uneven batch of stories, but definitely worth wading through the chaff for the wheat. Avram Davidson's The Sources of the Nile combines both in roughly equal proportions. The story begins with an encounter between the narrator, a down-on-his-luck writer, and a haggard old fellow who once was able to predict the whims of fashion with uncanny accuracy. Is it precognition? Time travel? Excellent taste? No–as the protagonist learns, the source of his success is a modest family in a modest apartment that just seems to know. Next year's popular books, next year's clothing fads. Well, the narrator is denied certain fortune when, after a glimpse of this locus of prescience, he loses contact with the family. He is thus doomed, like the guy who tipped him off, to search the world for this holy grail.

Davidson has adopted an avante garde style these days. At first, I was much impressed. After a dozen pages of over-cute overexertion, I was tired of it. I applaud innovation, but not at the expense of readability. Three stars.

Then we have Vance Aandahl's The Man on the Beach, sort of a poor man's The Man Who Lost the Sea. Aandahl is not Ted Sturgeon, and his short tale, of an astronaut who lost his ship to murderous aborigines, somehow misses the mark. Two stars.

But then there's the ever-reliable Cliff Simak with Shotgun Cure, in which an ostensibly benevolent alien visits a country doctor (how Cliff loves those rural settings!) and offers him a cure for every illness in the world. There's just one catch: it also lowers the intelligence of the cured. What price health! A fair idea told in excellent Simak style. Four stars.

Charles De Vet's The Return Journey is also worthy: What recourse exists when a colony of Terrans expands beyond the boundaries set by treaty with the native aliens? Sometimes the winning move is never to have played. Four stars.

Rehabilitated, by Gordon Dickson, is a cross between Keyes' Flowers for Algernon and Sturgeon's More than Human. A fellow seems ill-suited for work in the modern (read: near future) era. He is rescued from a life of crime by a do-gooder outfit that rigorously trains him for a new profession: planetary colonist. But it turns out that he is wholly unqualified for the job, having an IQ of just 92. What was the point, then? The organization is actually a network of telepathic misfits, all suffering from some degree of mental illness, from instability to retardation. Working together, they maintain a balance such that each member's strengths compensate for another's weaknesses. The training for colonization was just a a sort of dry run. I have "Three stars" listed in my notes, but upon reflection, I think I'll bump it up to Four.

This trio of excellence is followed by a twosome of mediocrity. William Eastlake's What Nice Hands Held is a story of romance, infidelity, poverty, status, and magical realism in an heterogeneous Indian lodge. Again with the trying too hard. The other is Robert Young's silly Hopsoil, about Martians visiting a post-apocalyptic Earth and raising a most unusual crop in our oddly fertile soils. Two stars for both.

Asimov's article this month, Here it Comes, There it Goes, is a bit of a disappointment. It's a summary of one of the current fads in cosmology, the idea that matter is created and disintegrated continuously, and that's how the Universe is, always has been, and always will be. The Good Doctor's arguments (which are, to be fair, not his) are not particularly compelling. Three stars.

F&SF is trying out poetry again. Lewis Turco's A Great Grey Fantasy didn't strike my fancy. Perhaps it will strike yours. Two stars.

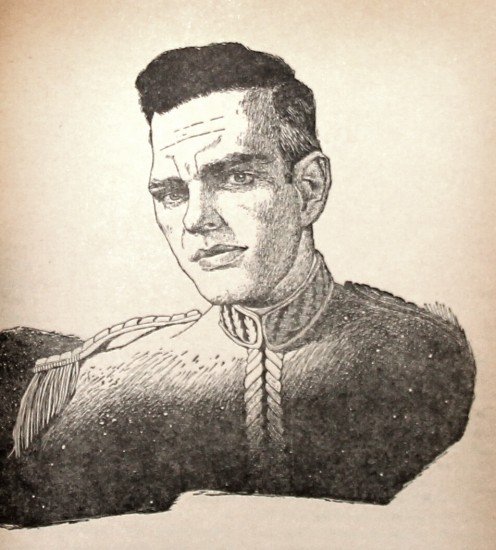

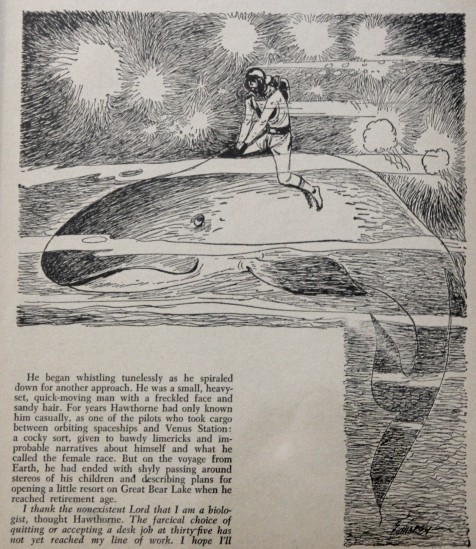

Rounding out the issue is a tour de force from an author who has been on fire these days, Poul Anderson. Time Lag is a gripping novelette of the attempted conquest of one Terran colony by another. It is told from the point of view of Elva, a married mother from the peaceful, apparently pastoral planet of Vaynamo. Her husband is killed and her village savaged by an advance party of Chertkonians lead by the ruthless Captain Bors. Elva is forced into the position of Bors' mistress, and while Bors is not particularly cruel about it, we are never made to forget that Elva is an unwilling partner.

Interstellar travel is a relativistic affair in this story. The journeys between Vaynamo and Chertkoi take fifteen years of objective time even though they take only weeks of subjective time. Thus, Time Lag is told in a punctuated series. Through Elva's eyes, we get a glimpse of the overcrowded and polluted Chertkoi, stiflingly authoritarian and caste-conscious. Elva is taken along for the second assault on Vaynamo, in which the capital is atomized from orbit. She bravely confers with a captured general under the guise of extracting intelligence and learns that the Vaynamonians, possessed of a highly advanced science themselves (as one would expect; they did come from star-travelling stock), are not quite so helpless as the Cherkonians have surmised. Elva uses her position as consort to the increasingly prestigious Bors to obtain a degree of succor for the Vaynamonian captives, though her efforts are never entirely successful.

The third assault from Chertkoi is the last. Thousands of ships, the fruits of the labor of billions of oppressed souls, are unleashed against Vaynamo, a planet with a population of just ten million. Bors, now a Fleet Admiral, is certain of his victory. But is it really assured?

What elevates this story above a simple good-versus-evil story is the parallel drawn between the planetary and personal conflicts. Elva has been enslaved, but she has not been defeated. Her strengths go far beyond the blatantly visible. Bors never breaks her; in fact, Elva quickly becomes his master, though he is never aware of the fact. Similarly, Vaynamo does not need to win by matching the vulgar rapacity of Cherkoi; rather, the world relies on compassion, deliberateness, and immense inner strength.

Time Lag is a refreshingly feminine story from a feminine viewpoint, something which Anderson has been getting pretty good at. I appreciated that there was no suggestion of taint upon Elva for her plight. Like Vaynamo, she endured violations and pain, but she emerged an unbroken heroine.

Five stars.

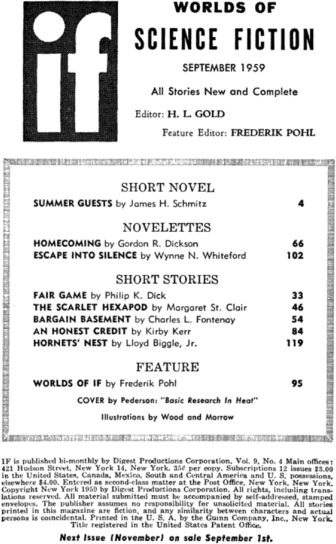

That comes out to an aggregate of 3.25 stars making F&SF the winning digest for the month (IF was just behind at 3.2, and Analog trailed far behind at 2.5). I think IF wins the best story prize, however, with Vassi, and IF certainly wins the "most woman authors" award, with two (the only ones to appear in all three magazines).

And now 1961 can truly begin!