by Gideon Marcus

Humans like to categorize things. Types of people, varieties of animals, kinds of music, boundaries of epochs. As an historian, I find the latter particularly interesting. The transition between ages is often insensible to those living in them. After the fact, we tend to compact them into tidily bounded intervals. The Gay '90s. The Roaring Twenties. The Depression. The War Years.

Decades from now, historians will debate when the "'50s" truly began and ended. Did they start with the armistice in Korea? Did they end with the election of Kennedy? Looking around, it's hard to draw a sharp line between Ike's decade and the current one. Things are changing, no doubt, but it's much of a muchness. The battle for Civil Rights continues. The Cold War endures.

If anything, this year feels like an interlude, that time of uncertain winds before the clouds march confidently in a new direction. You hear it in the political rhetoric. You see it in the fashion, with the flared skirts of last decade still living (though decreasingly) alongside the pencil-cut of the '60s.

And you particularly notice it in the musical trends. For instance, many of the genres of '50s are still with us. There are lots of new ones, however, competing for time on the airwaves. The last time this happened, it was 1955. For a brief time, swing, schmaltz, rock, and calypso competed for our ears' attentions. Once more, we have an unprecedented level of sonic diversity:

Pop

Pop, as a genre, has been around for several years. Ricky Nelson, Neil Sedaka, Bobby Darin were all big in the late '50s, and they're still tops today. A couple of big changes have occurred over the last few years. In 1960, we saw women entering the field more frequently. Ingenues like Rosie Hamlin (who recorded Angel Baby just a few miles from my house, Linda Scott, Brenda Lee (straddling the country line), and Kathy Young. Not to mention Little Peggy March (I will Follow Him) and Eydie Gorme…singing about the one Latin music form still popular in the States:

Blame it on the Bossanova, by Eydie Gorme

Individual girl singers seem to have peaked in popularity last year, though, giving way to Black girl-groups like the Chiffons, the Crystals, the Shirelles, and the Ronettes, which also began hitting the charts around 1960.

Producer Phil Spector is a big force behind these groups, introducing a new concept in music called "The Wall of Sound" that loops in huge numbers of strings and layered vocals to weave a rich tapestry of music. You can hear his work in hits like…

He's sure the boy I love, by the Crystals

And on the other side of the Pond, we have British artists that sometimes get airplay over here. Occasionally, I hear an import from Cliff Richards, the crooner front-man for The Shadows. His latest soundtrack topped the charts in the UK for a while, though it's since been knocked off by a newcomer band that is still virtually unknown in the States:

Please Please Me, by the Beatles

Motown

Both a style and a label, Motown is a Detroit-based record company producing a slick evolution of DooWop, Soul, and R&B feauturing hits like:

Let me go the Right Way, by The Supremes

Come and Get these Memories, by Martha and the Vandellas

I have a feeling this may be the next big thing…if it can break out of the Steel belt and the Negro stations.

Surf

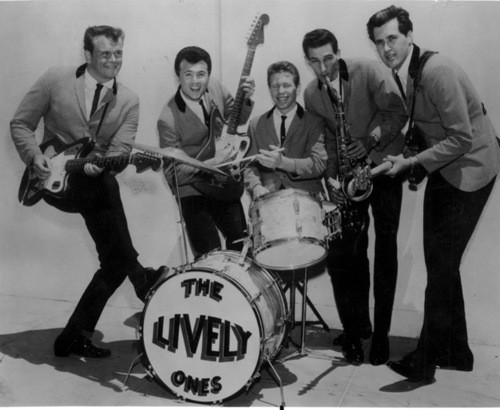

Out of the prototypical instrumental music days of the late '50s, typified by folks like Duane Eddy and Link Wray, the genre has come full flower. It started in 1960 with the Ventures and The Shadows, with their intricate renditions of standards like Ghostriders in the Sky and Apache. Then someone figured out how to send strummy vibrato into a speaker (probably Dick Dale, the self-crowned "King of the Surf Guitar), and now the airwaves are filled with that fluttery, tubular, sound that's straight out of the ocean. Numbers like:

Surf Rider, by The Lively Ones

Country

With the recent death of the Queen of the Grand Ole Opry, Patsy Cline, it's worth taking stock of who our luminaries in the Country genre. This is a genre I've been a fan of ever since The Sons of the Pioneers and Hank Williams were twanging Western and Honky Tonk.

Patsy Cline's Crazy, written by Willie Nelson

Another country star who came out of the 50s and is still going strong is (my favorite), Wanda Jackson:

Whirlpool (sounds like a modern redo of Funnel of Love)

And you've probably heard Skeeter Davis' latest country-pop crossover hit:

The End of the World, by Skeeter Davis

Folk

Out of the culturally meaningful, commentary-laden folk songs of the 1950s, two main movements have formed. The first, exemplified by new star, Bob Dylan, hews closely to its roots. Dylan's voice is as friendly as a buzzsaw, and his guitar is unadorned. But what he sings sounds like the truth.

The second is the harmonious, still simple, but beautifully polished works by earnest bands like The Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul, and Mary, as well as more playful stuff, for instance by The Rooftop Singers.

The New Frontier by The Kingston Trio

Puff the Magic Dragon by Peter, Paul, and Mary

Walk Right In by The Rooftop Singers

It's difficult to tell which school will in out in the end, but as the 1960s promise to be a turbulent decade, with the fight for Civil Rights and the wars in Indochina heating up, one can bet Folk will be with us throughout.

Jazz

Once king in the 30s and 40s, Jazz has become more of an aesthete's bag. There are dedicated stations and a semi-regular TV show, Jazz Casual, and plenty of records, but Jazz is definitely not found on the popular airwaves.

Plenty of older artists, like Count Basie, Dexter Gordon, and Duke Ellington remain active, along with mid-rangers like John Coltrane, Earl Bostic, and Dave Brubeck.

The new big thing (though it's been around since the '50s) is "Free Jazz" or "avante-garde" which cares not for fixed chord progressions and time signatures. At its free-est, it's almost incomprehensible, but tamed, it's exotic and vibrant.

Straddling the jazz and Latin line is Cal Tjader, a '50s vibraphone phenomenon who continues to be popular (you should see my nephew, David, cut a rug to this stuff…)

—

Of course, this is just a thumbnail sketch of what's out there, and I haven't even touched foreign movements like Jamaican Ska or Brasilian Bossanova. With so many different genres struggling to catch the public's ear, it's hard to place bets on which ones will be ascendant in the years to come. For now, sit back, relax, and enjoy the unrivalled musical diversity while it lasts.

What's YOUR favorite genre/artist?

(If you want to hear these hits and more, tune in to KGJ — Galactic Journey radio plays the newest and the mostest!)

–