by Gideon Marcus

Murder in Hollywoodland

Senseless mass death is no stranger to the headlines these days. We've had the Boston Strangler. The Texas sniper. The Chicago nurse murderer. But this last week, southern California got a shocking introduction into this club.

At least seven were killed on the nights of the 8th/9th and then the 9th/10th, including Valley of the Dolls actress, Sharon Tate (pregnant with her first child), in two Los Angeles neighborhoods: ritzy Beverly Crest and SilverLake. At first, the scenes were so grisly and bizarre that police suspected some kind or ritual. Jay Sebring, the famous hairstylist who gave Dr. McCoy his "brainy" JFK-style hair-do, and Tate were found stabbed, tied up and hanging on alternate sides of the same rafter, both wearing black hoods. Market owners Leon and Rosemary La Bianca, the SilverLake victims murdered on the second night, were similarly hooded, the latter with red X marks carved into her body.

Wheeling Sharon Tate from her home

Homicide squads are currently swarming the San Gabriel Valley, and while Inspector Harold Yarnell and medical examiner Thomas Noguchi had no insights to offer when they appeared before NBC's cameras on the 10th, police do see connections. "Pig" was scrawled on the door of the Tate home, while "Death to Pigs" was found on the home of the La Biancas, formerly the residence of Walt Disney. Police have not indicated whether they believe the homicides were done by the same person or persons, or if a copycat was inspired by the first murders.

It's shocking, senseless, and tragic. While the murders took place in upper class homes (one of the deceased was heir to the Folger coffee fortune), the motive appears not to have been robbery. Just angry, hateful death. It's not a happy time in the Southland right now.

Death in New York

While not of the same magnitude, at least in terms of human misery, nevertheless the latest issue of Galaxy science fiction is so bad, that one wonders if someone is trying to put the institution down.

by Donald H. Menzel

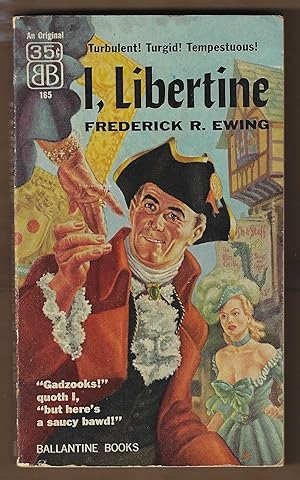

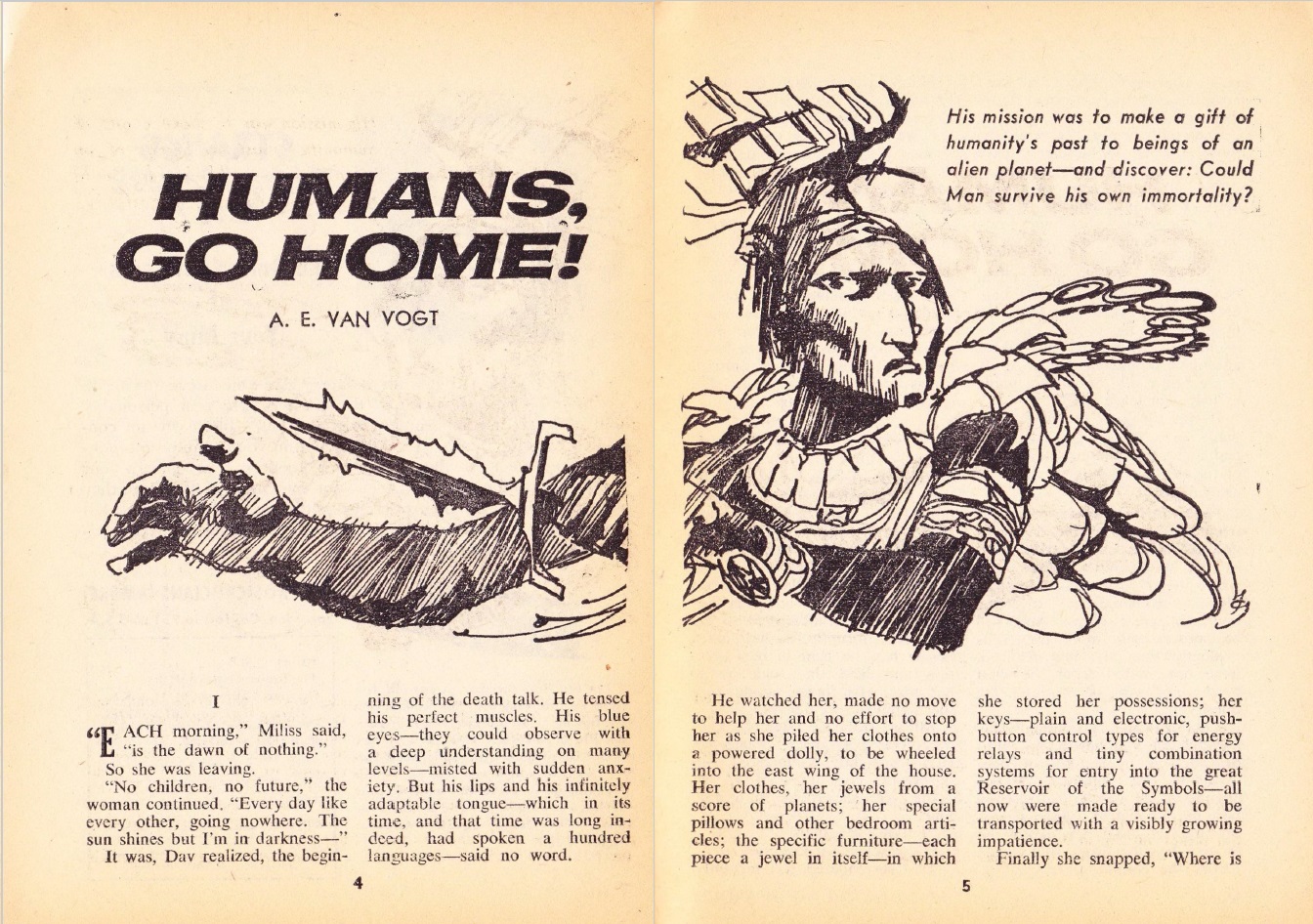

Humans, Go Home!, by A. E. van Vogt

by Jack Gaughan

A married human couple, immortal but catching the death-wish that has killed most of humanity, has lived on the world of Jana for 400 years. They have used that time to accelerate the development of the humanoid species there, urging 4000 years of technological advance in that time—in part through the use of Symbols, abstract concepts made real by the power of belief. The Janans have their own problems: the women don't like procreation or children, and the men must rape them to propagate the species.

Eventually, the humans are put on trial for their efforts, and (I'm told) we learn there is a lot more to the setup than meets the eye, and that everything the characters believe is actually some kind of falsehood.

I found this first piece impenetrable, giving up about halfway through. Thankfully, a friend of mine, who is fonder of Van Vogt, gave the piece a write up in his 'zine. That's good, as I was dreading having to slog through this one and analyze it, as if it were a book report for a hated school-assigned novel. At 50 years old, I'm allowed to pick my poison.

One star.

Martians and Venusians, by Donald H. Menzel

by Donald H. Menzel

Professor of Astronomy and Planetary Sciences at Harvard offers up his clairvoyant images of Martian wildlife, complete with pictures (q.v. the cover). I wonder if Dr. Menzel has an eight-year old child who really wanted to get published, as well as some blackmail leverage on Galaxy editor Jakobssen, because I can't see any other way this peurile, pointless piece ever saw print.

One star.

Out of Phase, by Joe Haldeman

Braaxn the G'drellian is the adolescent member of an alien anthropological team. He was selected to infiltrate the humans for his shape-changing abilities; unfortunately, the youth also has a racial fetish for the infliction and appreciation of pain—common to all of his kind at that age.

Can he be stopped before he unleashes a terror that will exterminate the entire human race?

An unpleasant, but competently written story. Haldeman is new, so of course, there's a "clever" twist to finish things off.

Three stars

The Martian Surface, by Wade Wellman

Wellman's wishful thinking in poetry is that, despite the obvious hostility of the Martian surface, life could still somehow cling to it. Written to coincide with the arrival of the new Mariners, it is no more or less accurate for their flyby.

Three stars.

Passerby, by Larry Niven

by Jack Gaughan

A ramscoop pilot stumbles upon a professional people-watcher in a park. The "rammer" has a story to tell, a tale of being lost among the stars, and of the titanic alien he encounters in the blackness of space.

This is one of Niven's few stories not set in "Known Space", and it's a simple one. That said, it reads well, particularly out loud, and there is the usual, deft detail that Niven imparts with just a few, well-chosen words.

Janice liked it, but thought it rather shallow. Lorelei, on the other hand, loved that it had a philosophical message beyond the good storytelling.

So, four stars, and easily the best piece of the issue (not much competition…)

Citadel, by John Fortey

by Jack Gaughan

Aliens descend on Earth, erecting mysterious edifices and offering the secrets of the universe. Twenty years later, most of humanity is under their thrall; those who enroll for alien "classes" invariably leave society and end up part of the worldwide hive mind. One organization has a plan to infiltrate the extraterrestrials, to at least find out what's going on, if not stop them.

But can they handle the truth?

Answer: probably, especially if they've seen The Twilight Zone.

Nice setup, but a really novice tale.

Two stars.

Revival Meeting, by Dannie Plachta

by M. Gilbert

A "corpsicle" wakes up after a century, but instead of finding a cure for his disease, he finds he's been roused for a more sinister purpose.

This story doesn't make much sense, and it's also about the bare minimum one can do with the concept of frozen people (again, Niven's covered these bases pretty thoroughly with The Jigsaw Man and A Gift from Earth.

Two stars.

For Your Information (Galaxy, September 1969), by Willy Ley

For reasons that will shortly become apparent, it's a real pity that this non-fiction column is not one of Ley's best. It's a scattershot on rocket fuel (well, the oxidizer one combines with the rocket fuel to make it burn), modern pictographic writing, and the latest crop of satellites.

It's just sort of limp and dry, a far cry from the scintillating stuff that helped make early '50s Galaxy such a draw.

Three stars.

Dune Messiah (Part 3 of 5), by Frank Herbert

by Jack Gaughan

It is astonishing how little Frank Herbert can pack into 50 pages. In this installment, Paul Atreides, Emperor, is trying to make sense of a recurring vision, that of a moon falling (his precognition having been hampered by the presence of a clairvoyant "steersman"—the spice-addicted navigators of the space lanes).

He visits the Reverend Mother of the Bene Gesserit, whom he has locked up in prison, to let her know that his consort, the Fremen Chani, is finally pregnant (despite Paul's wife, Irulan, furtively feeding her contraceptives for years). But Paul also knows that the birth of the heir will mean Chani's death.

Then Paul heads out to the house of a desert Fremen, father of the girl who had been found dead by Alia last installment. The Emperor heads out there at the girl's invitation—she's not actually alive, but rather, her form has been taken by a shapeshifting assassin.

At the home, Paul meets a dwarf who warns him of impending danger. Whereupon, an atomic bomb explodes overhead.

Along with the endless viewpoint changes and the nonstop italicized thought fragments, we also have more of the innovation Herbert came up with for this book: repetition of dialogue through slightly different permutation. Seriously, the whole story so far could have been a novelette, and we're almost done!

Anyway, I didn't hate Dune, but I felt it was overrated. This sequel, however, is just wretched.

One star.

Credo: Willy Ley: The First Citizen of the Moon (obituary), by Lester del Rey

by Jack Gaughan

And now the real tragedy—Willy Ley is dead. He was only 62.

I knew that he was a science writer who fled Nazi Germany. I did not know how integral he was to the field of rocket science. A key member of the German rocketry club, he was a mentor to Wehrner von Braun. The key difference between the two is Ley immigrated to the U.S.A. rather than serve Der Fuhrer. Von Braun did not.

Ley went on, of course, to be one of the most esteemed science writers—up there with Asimov, at least in his main fields, zoology and rocketry. He died less than a month before Armstrong and Aldrin stepped on the Moon. Denied the Holy Land, indeed.

I have no idea whether there are more Ley articles in the pipeline. There was supposed to be a new, twelve-part series, but who knows if it was ever completed or submitted.

Sad news indeed. Four stars.

Autopsy report

Galaxy hasn't topped three stars since the June hiatus accompanying editor Pohl's departure/sacking, but this is, by far, the worst issue of the magazine in a long time. Was Pohl fired for his declining discernment? Or did he accept a bunch of substandard stuff as a flip of the bird to the new ownership?

Whatever the answer, I certainly hope things improve soon. Without Ley, without quality stories, Galaxy is heading for the skids, but quick.

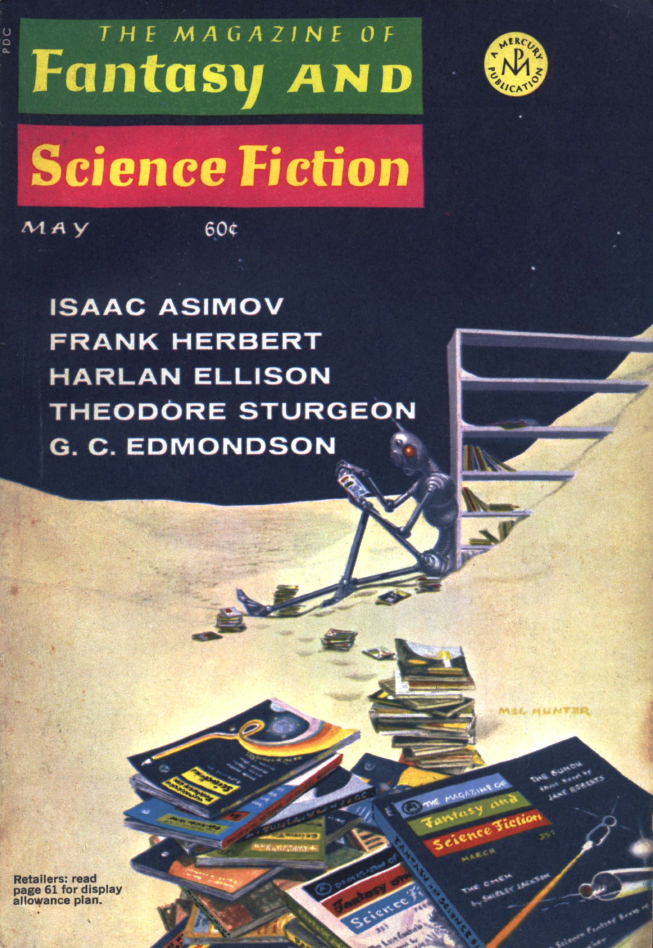

![[April 20, 1970] Not the final quarry (May 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700420fsfcover-653x372.jpg)

![[March 31, 1970] Seed stock (April 1970 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700331analogcover-672x372.jpg)

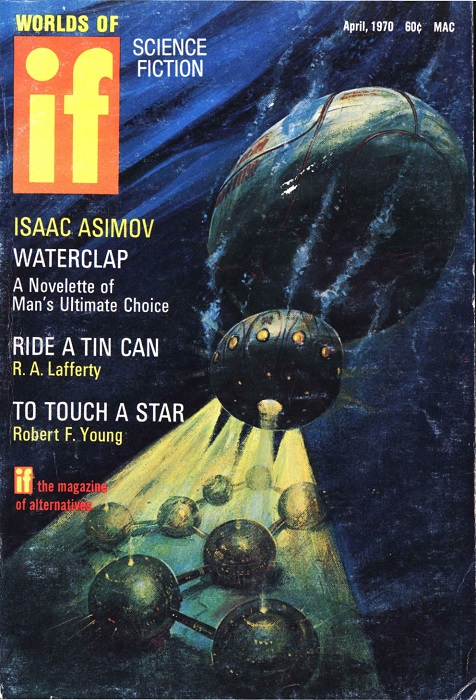

![[March 2, 1970] Par for the course (April 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IF-1970-04-Cover-476x372.jpg)

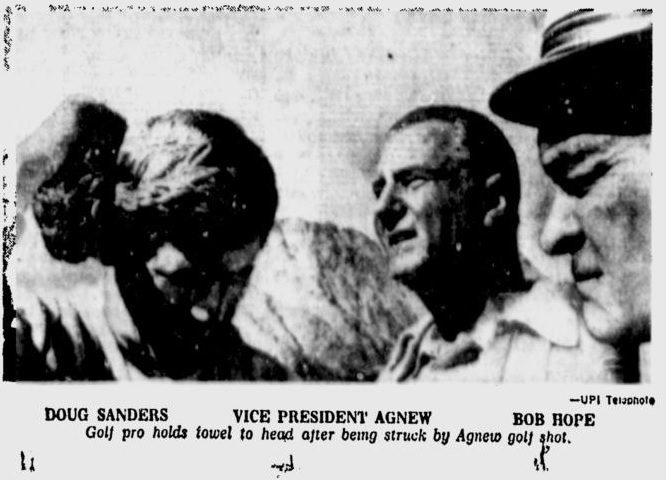

Wire photo of the aftermath.

Wire photo of the aftermath. Arrival at Ocean-Deep. Art for “Waterclap” by Gaughan

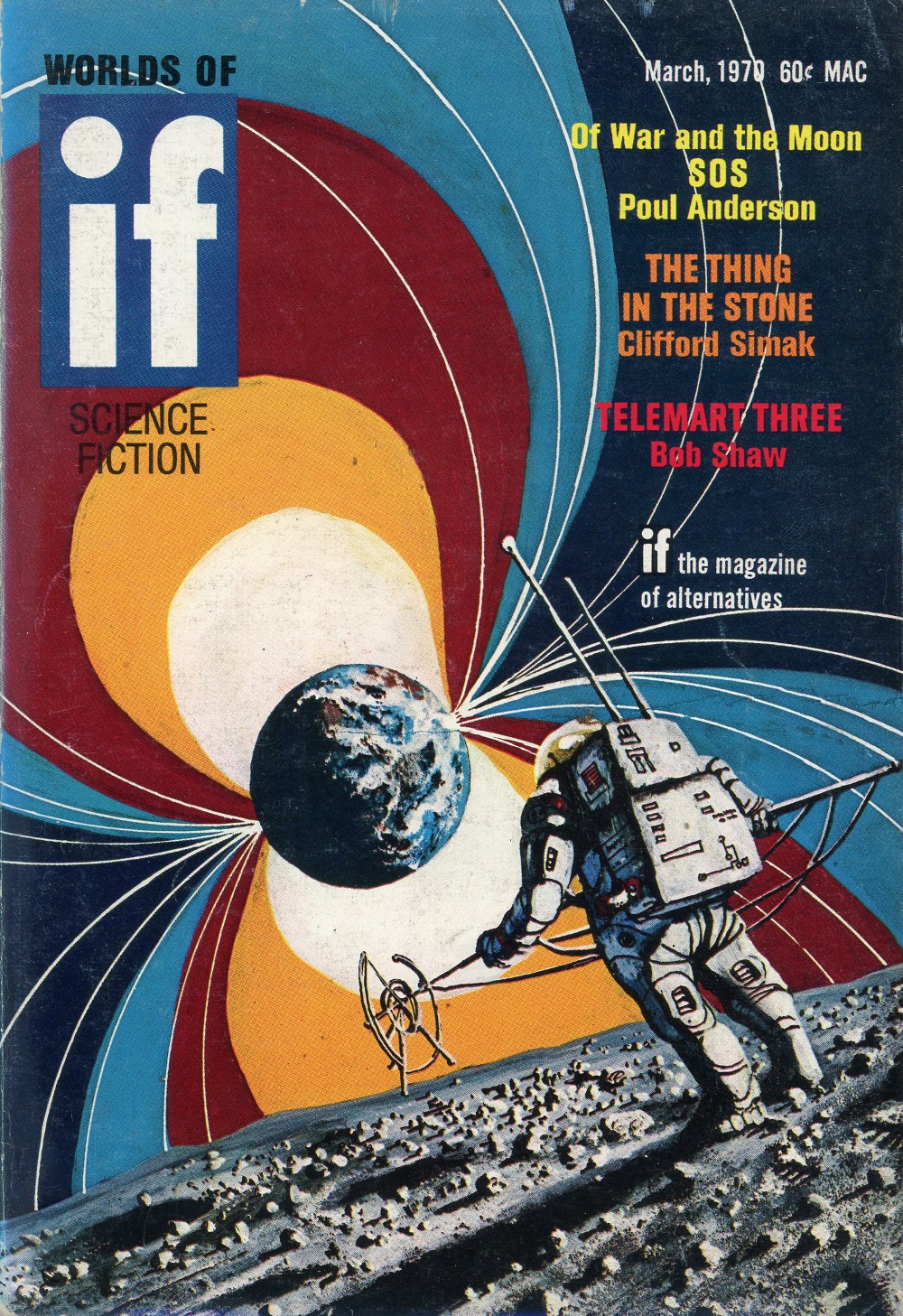

Arrival at Ocean-Deep. Art for “Waterclap” by Gaughan![[February 2, 1970] Deceptive Appearances (March 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/IF-1970-03-Cover-479x372.jpg)

The arbiter, an NCR 315.

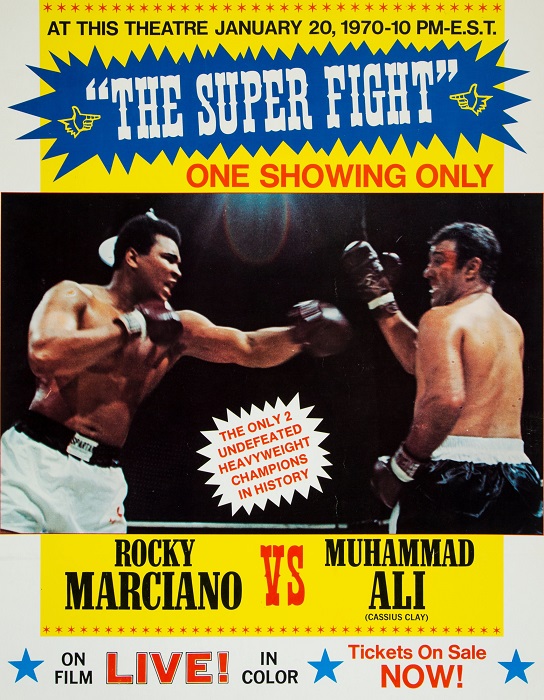

The arbiter, an NCR 315. Movie poster for the event. That “LIVE!” is a little deceptive, which is something else Ali is complaining about.

Movie poster for the event. That “LIVE!” is a little deceptive, which is something else Ali is complaining about. Art actually for “SOS,” rather than just suggested by. Maybe because it’s by Mike Gilbert, not the overworked Jack Gaughan.

Art actually for “SOS,” rather than just suggested by. Maybe because it’s by Mike Gilbert, not the overworked Jack Gaughan.![[January 2, 1970] Under Pressure (February 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IF-1970-02-Cover-500x372.jpg)

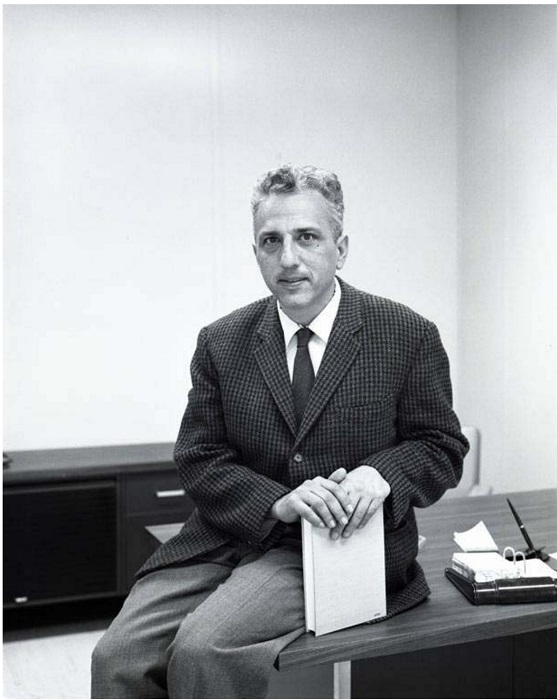

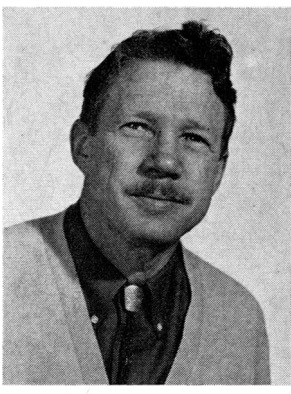

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California

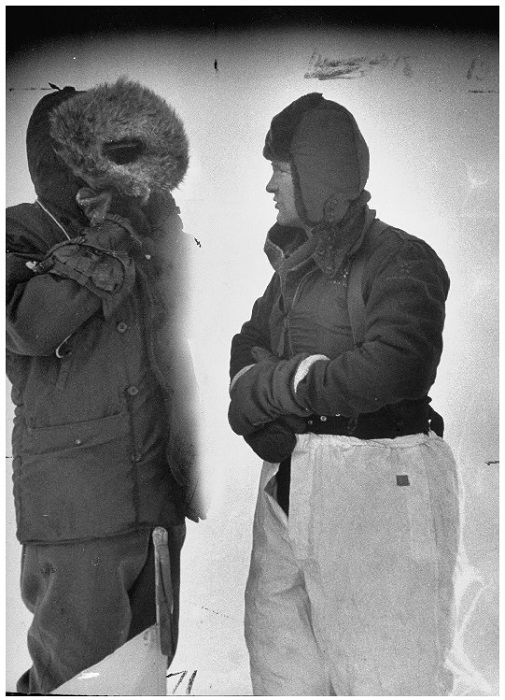

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find.

Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find. Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado

Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.

Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.![[December 2, 1969] Communication Breakdown (January 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/IF-1970-01-Cover-478x372.jpg)

Vice President Spiro Agnew addressing the Midwest Regional Republican Committee.

Vice President Spiro Agnew addressing the Midwest Regional Republican Committee. White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler

White House Press Secretary Ron Ziegler![[September 12, 1969] Earthshaking (October 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/690912galaxycover-397x372.jpg)

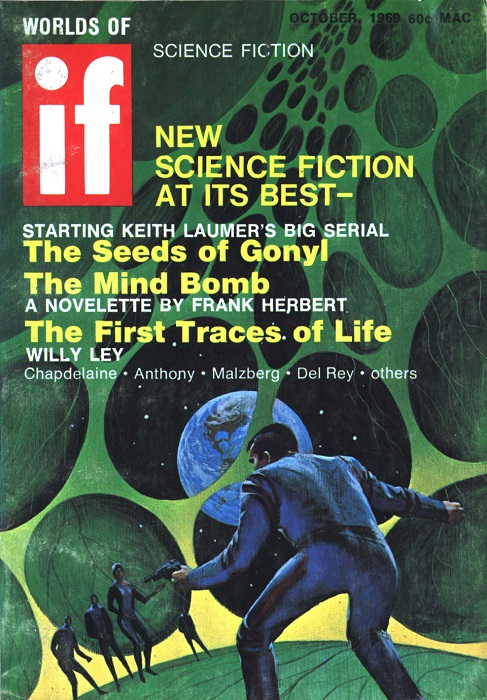

![[September 4, 1969] <i>Plus ça change</i> (October 1969 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/IF-1969-10-Cover-487x372.jpg)

Penelope Ashe, in part, with the cover model superimposed.

Penelope Ashe, in part, with the cover model superimposed.

Supposedly for Seeds of Gonyl. If so, it’s from later in the novel. Art by Gaughan

Supposedly for Seeds of Gonyl. If so, it’s from later in the novel. Art by Gaughan![[August 14, 1969] Twin tragedies (September 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/690814galaxycover-417x372.jpg)

![[July 8, 1969] Nowhere fast (August 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/690708galaxycover-450x372.jpg)