by David Levinson

The popular image of a mirage is a shining oasis in a desert replete with shady palm trees and sometimes dancing girls. That’s not how mirages work. We’re all familiar with heat shimmer, say on a hot, empty asphalt road, casting the image of the sky onto the ground and resembling water. Less common is the Fata Morgana, which makes it look as though cities or islands are floating in the sky. But the popular idea of the mirage remains: something beautiful and desirable, yet insubstantial.

Heat Wave

July was a real scorcher in the United States as a heat wave settled in over much of the Midwest. A heat wave might make a fun metaphor for passion if you’re Irving Berlin or Martha and the Vandellas, but as the latest hit from the Lovin’ Spoonful suggests, it can be a pretty unpleasant experience. As the mercury rises, people get pretty hot under the collar.

On July 12th, the Black neighborhoods on Chicago’s West Side exploded. The sight of children playing in the spray of a fire hydrant is a familiar one, but the city’s fire commissioner ordered the hydrants closed. The spark was lit when, while shutting off the hydrants, the police attempted to arrest a man, either because there was a warrant for his arrest (according to them) or because he reopened a hydrant right in front of them (according to the locals). As things escalated, stores were looted and burned, rocks were thrown at police and firemen and shots were fired. There were also peaceful protests led by Dr. Martin Luther King. Mayor Daley called in the National Guard with orders to shoot. Ultimately, the mayor relented. Police protection was granted to Blacks visiting public pools (all in white neighborhoods), portable pools were brought in and permission was given to open the hydrants.

Children in Chicago playing in water from a reopened hydrant

As things wound down in Chicago, they flared up in Cleveland. On the 18th in the predominantly Black neighborhood of Hough, the owners of the white-owned bar the Seventy-Niner’s Café refused ice water to Black patrons, possibly posting a sign using a word I won’t repeat here. Once again, there was looting and burning and the National Guard was called in. Things calmed after a couple of days, but heated up again when police fired on a car being driven by a Black woman with four children as passengers. It appears to be over now and the Guard has been gradually withdrawn over the last week. City officials are blaming “outside agitators” for the whole thing.

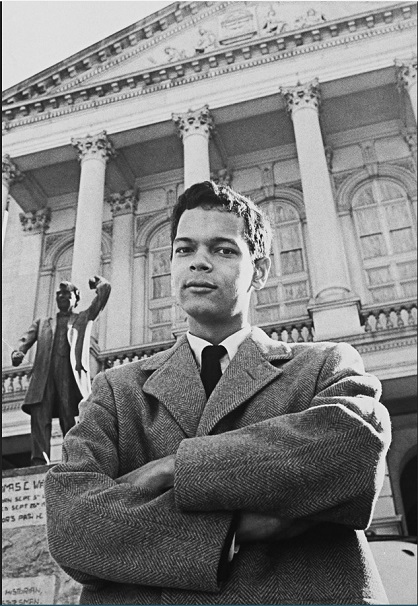

These riots are a stark reminder that the passage of the Civil Rights Act two years ago didn’t magically make everything better, and that problems also exist outside of the South. We have a long way to go before racial equality is more than just wishful thinking.

National Guardsmen outside the Seventy-Niner’s Café

Pretty, but insubstantial

Some of the stories in this month’s IF are gorgeously written, but lacking in plot. Sometimes that’s enough, sometimes it isn’t.

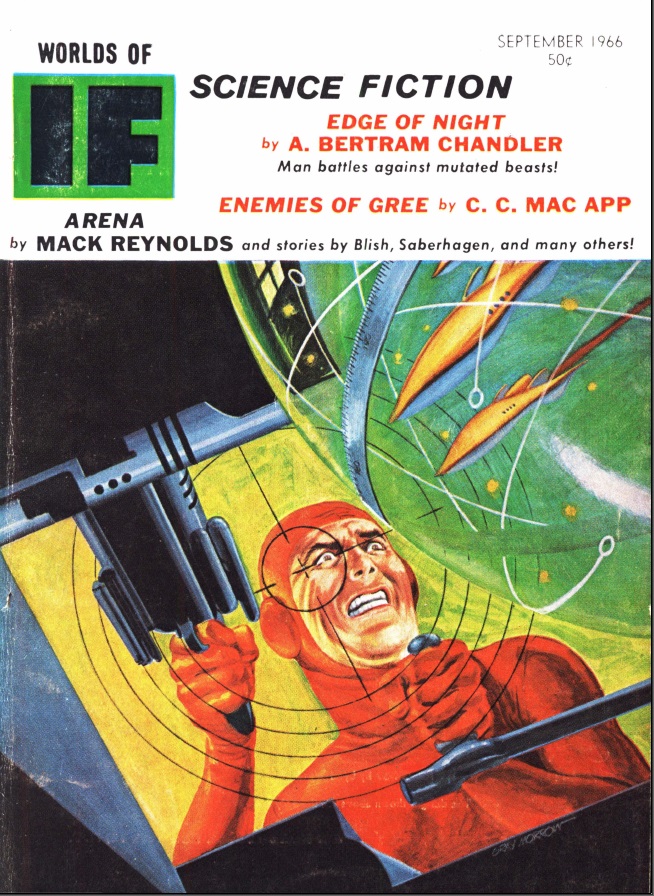

This fellow’s having a very bad day, but he’s not in The Edge of Night. Art by Morrow

Continue reading [August 2, 1966] Mirages (September 1966 IF)

![[August 2, 1966] Mirages (September 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/IF-1966-09-Cover-654x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1966] The Big Thud (August 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/IF-1966-08-Cover-644x372.jpg)

![[June 2, 1966] Bad Decisions (July 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/IF-1966-07-Cover-654x372.jpg)

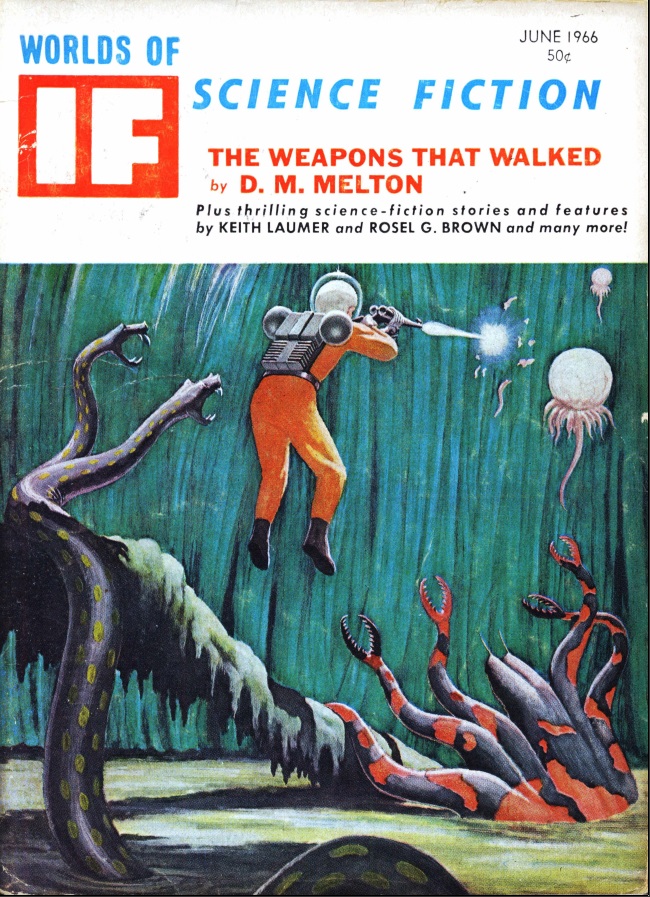

![[May 2, 1966] By Any Other Name (June 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/IF-1966-06-Cover-650x372.jpg)

![[April 2, 1966] Hidden Truths (May 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/IF-1966-05-Cover-659x372.jpg)

![[March 2, 1966] Words and Pictures (April 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IF-1966-03-Cover-1-657x372.jpg)

![[February 8, 1966] Feeling A Draft (March 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/IF-1966-03-Cover-641x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1966] Keep Watching the Skies (February 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/IF-Cover-1966-02-652x372.jpg)

![[December 2, 1965] Superiority Complex (January 1966 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/IF-1966-01-Cover-646x372.jpg)

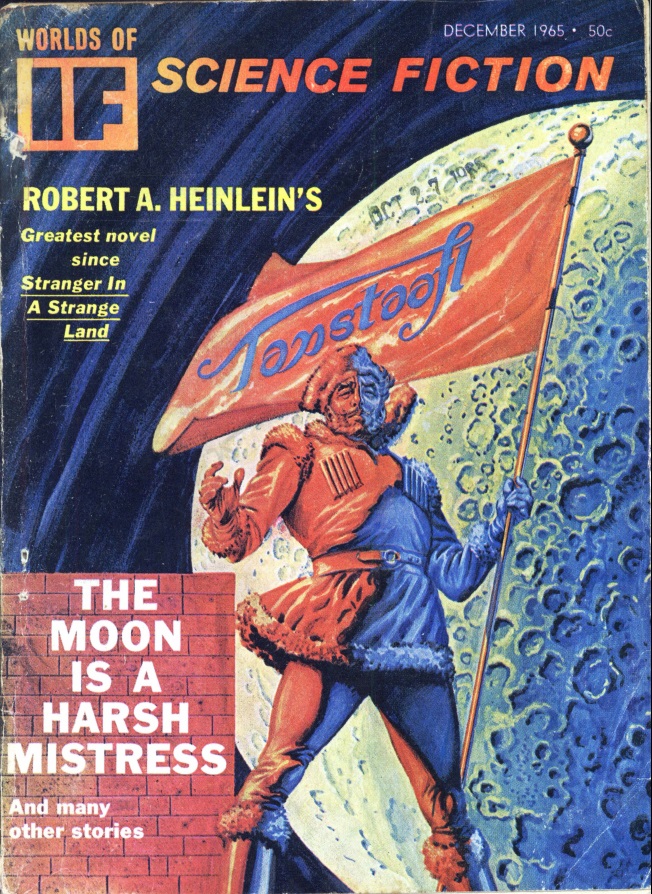

![[November 2, 1965] Revolution! (December 1965 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/IF-1965-12-Cover-652x372.jpg)