No Tribble at All

by Joe Reid

Following on the heels of an episode that I found to be problematic, with the introduction of the outer space ghostly version of Jack the Ripper, Star Trek fans everywhere have been gifted with an episode that is a successful combination of the sci-fi and comedy genres. Brothers and sisters, “The Trouble with Tribbles” was well written, well-acted, and well scored. It was not just good sci-fi and good TV; I would go as far as considering it an instant classic, a technicolor rendition of some of my favorite comedies in the vein of Dick Van Dyke or Lewis and Martin.

The episode started off giving a small a hint to what was in store. The Enterprise was speeding along in space. Kirk, Spock, and Chekov were meeting to discuss the upcoming mission to Space Station K-7. It is at the meeting that Chekov makes a quip about the Klingons being so close to K-7 that we could smell them. It’s then that Spock jumped in, playing the straight man, letting him know that smelling people in space was illogical. The actor who played Chekov was able to stretch his comedic legs in this episode. The young man took almost every opportunity to make funny statements about how everything was either discovered by or invented by Russians.

Davidushka Ivanov, now sporting his own hair!

Soon after the Enterprise got an emergency distress call from the K-7 space station. They rushed in to come to the rescue with their phasers ready to blast and found that there was no emergency or attack to speak of. Kirk was angered by this and butted heads with the Federation official that was just the type of weasel to get under Kirk’s skin. It was here where we started to see a series of gags being set up. We had one situation where everyone else knew about a magical new grain except Kirk, which irked him to no end. Scotty turned from bookish to a bad influence on young officers by getting into a fight when someone insulted the Enterprise. A salesman named Cyrano Jones, trying to make a few space bucks and get free drinks from the bar on K-7, unleashed a locust swarm of cute, furry, rapidly multiplying critters that ended up getting in everything, everywhere. These "tribbles", the namesake of the episode, were the glue that bound this ensemble together. Yes, they were troublesome, but it was in a way that made for a fun time.

Enough fun for everyone!

By ensemble I also mean the cast. All the actors had plenty of lines and were important to the story, the Klingons included. We also saw the crew showing off comedic timing, slapstick antics, and giving each other funny looks when things went awry. All of the characters and situations that were set up in the episode were hilarious and served the story well. The tribbles and the Klingons made this episode very Star Trek and the wonderful acting made the comedic notes hit their marks.

"Hey, plebe in the back–thanks a lot for the help!"

By the end of the episode there were a mess of tribbles, a mess of a brawl, and a mess of a situation that Kirk and crew had to fix. Which they did to the satisfaction of all. I’ve purposefully kept the small details of the episode to myself, so as not to diminish the joy of anyone who hasn’t seen this episode. This episode needs to be watched. Check your local listings to find out when the next airing happens in your area. It will be worth your time.

Five stars

Cute, but Dangerous

by Robin Rose Graves

It’s easy to understand the appeal of Tribbles. Soft fur, sweet purring to melt your heart and a friendly disposition (that is, if you aren’t a Klingon). It’s no wonder someone thought these would make an excellent pet! Or the perfect merchandise, as Cyrano Jones noted, their prolific nature made for easy stock.

As Bones investigated Tribble biology after Lt. Uhura agreed to part with one of her Tribbles’ offspring, he concluded that Tribbles are “born pregnant” or “bisexual” in nature, meaning they are capable of impregnating themselves. This made me wonder what kind of environment Tribbles originated from that would cause them to evolve these unique features. For one, they are obviously a type of prey, producing more offspring than will live to maturity. Not only are Tribbles prolific, but they waste no time in reproducing, suggesting that Tribbles have a short lifespan and are so endangered in their native environment that they can’t waste time in finding a mate. If a Tribble does not immediately produce, they risk extinction.

But while not actively aggressive, Tribbles proved to be, as the episode title suggested, troublesome.

Not to mention cumbersome.

Without their natural predators to keep their numbers in check, Tribbles multiplied out of control. In this episode, it was rather comedic how they spread throughout the Enterprise and gobbled up an entire supply of grain. But imagine if this episode took place on planetside instead, how devastating the effects of these adorable little critters could be. They live to eat and reproduce and as we’ve seen with the grain, Tribbles never seem to get their fill. On a foreign planet without predators, they would devour entire crops and local flora into extinction, causing colonies to starve, as well as any other grazing alien life – and should those grazing prey die, their predators would in turn starve. Tribbles might be the universe’s cutest bioweapon. Clearly there are laws to prevent the spread of harmful alien life, as at the end of the episode, Cyrano Jones faces 20 years in prison.

On the other hand, if Tribbles are edible and nutritious for humans, I’d argue they’d make the perfect source of protein for space traveling vessels.

"Tribbles and beans for dinner again?"

Even if Tribbles aren't tasty, they probably will make for some tres chic fur coats.

The concept of invasive species (a la rabbits in Australia) is an interesting aspect of space travel which science fiction doesn’t often address. This episode does so well and all the while being delightfully entertaining.

Five Stars.

A soldier, not a diplomat?

by Erica Frank

One of the fascinating parts of this episode was comparing Kirk's interactions with the Klingons to those with his own government officials.

With captain Koloth of the Klingons, he is cordially hostile: Both he and they are aware that their governments are rivals, bordering on enemies. There is no official warfare between them, but they both seem to know it's coming someday. They smile and talk politely while they are both aware that they would cheerfully kill each other to protect their people.

The station master does not have the authority to deny them access, but Kirk apparently does, since he can set rules about their visit. But he also knows that just saying "go away" without reason will escalate the hostilities, so he confines himself to requiring guards on them. There's no way to know if the resulting bar fight was better or worse than whatever would have happened if the Klingons had had free access to the station.

Nobody is happy to be here and yet everyone is smiling. Except for Spock. He doesn’t count.

On the other hand, we have Kirk's relations with Baris, the Agricultural Undersecretary. With him, he is not cordially hostile, but shows outright, direct animosity. He chafes under the forced authority. This is not because he can't follow orders (he obeyed the "Code 1 Emergency" call without question), but because he believes the Undersecretary has poor judgment and is wasting valuable resources–that is to say, the Enterprise's resources and crew's time. And he's not at all shy about telling him, even in front of the Klingons, that he's unhappy to comply.

In the end, the Undersecretary's fears were pointless; no number of guards could have protected the already-poisoned grain. And the presence of the Klingons turned out to be a blessing: without them, and the tribbles' shrieking anger (or fear), they would not have identified Darvin. They might have noticed that the tribbles didn't like him–but without the Klingons for comparison, they wouldn't have known why. They probably would not have uncovered his role as an enemy agent.

We don't have any evidence that Koloth was aware of the plot at all, but once it was discovered a Klingon agent poisoned the grain, he'd be under heightened scrutiny. Kirk gives him an easy out: Leave the area immediately, and nobody has to go through an interrogation that might kick off a war. Kirk can afford to be generous; after all, they did provide him a convenient way to spot their turncoat.

The only question left in my mind: Who are the people of Sherman's Planet, and why don't they get to choose which government will rule their skies?

Five stars.

Strange new worlds

by Lorelei Marcus

I appreciate any Star Trek episode that expands the scope of its fictional universe, but "Trouble with Tribbles" was a special treat. We get an expansion of the Federation's internal structure and range of command: not only is there an undersecretary of agriculture, but the Federation appears to be directly responsible for new colony projects. Private venture still seems to be a driving motivation for the seeding of new planets, but the Federation is in charge of approving and carrying out the operation as the central governmental figure in the universe. The Enterprise and her twelve sister ships comprise Starfleet, the Federation's military arm, tasked to defend against hostile alien empires.

Speaking of which, we also get our third glimpse of the Klingons, still at odds with Starfleet over space territory, and our first mention of the Organian Treaty after its establishment. The Treaty plays a decent role in the episode, and it's so refreshing to see a science fiction series utilize elements from previous episodes to create a believable and concrete universe. I enjoyed the anthology format of Twilight Zone, and even the more episodic nature of the first season of Star Trek, but I am loving this new direction for continuity across episodes even more.

My favorite part of this week's show, however, was the variety of new characters and locations. Getting to see several rooms in and the exterior of the deep space station K7 was very exciting. The completely new sets and models brought the station to life, and emphasized how narrow our perspective on The Enterprise really is. The adventures on Kirk's ship are but a narrow sliver of the possible stories to be told in the Star Trek universe.

Dig this nifty two-person transporter!

Furthermore, this was one of the few instances we get to see members of the Federation who are not part of Starfleet. The tribble tradesman in particular interests me, because he represents a world of people we have yet to see. Nearly everyone we've encountered so far comes from fairly similar backgrounds, either Starfleet Academy trained, a colonist, or an alien. Cyrano Jones is just an asteroid-hopping merchant, probably with little traditional education, and from unknown origins. He is the common man, working to earn enough credits to make a living, and the type of person we hardly see as we are led to the fringes of the galaxy aboard The Enterprise. He reminds us that there are billions of people out there within a thriving bureaucratic and economic structure that spans the galaxy, all of which is just offscreen. Never before have I seen such an ambitious attempt to portray a universe with such depth through the medium of television.

Five stars.

This is the face you'll be making if you don't join us for Trek tomorrow!

Join us at 5:00 PM Pacific (8:00 Eastern) or at 8:00 PM Pacific (11:00 Eastern)!

La Balsa puts to sea.

La Balsa puts to sea. The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high.

The Ra II under way. Note the tether keeping the stern high. Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by “Time Piece”. Art by Gaughan

![[June 4, 1970] Something old, something new (July-August 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/IF-1970-07-Cover-472x372.jpg)

![[April 10, 1970] A Style in Treason (May 1970 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700410galaxycover-651x372.jpg)

![[April 2, 1970] Being Human (May-June 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/IF-1970-05-Cover-472x372.jpg)

Archbishop Makarios III visiting the Greek royal family in exile in Rome earlier this year.

Archbishop Makarios III visiting the Greek royal family in exile in Rome earlier this year.

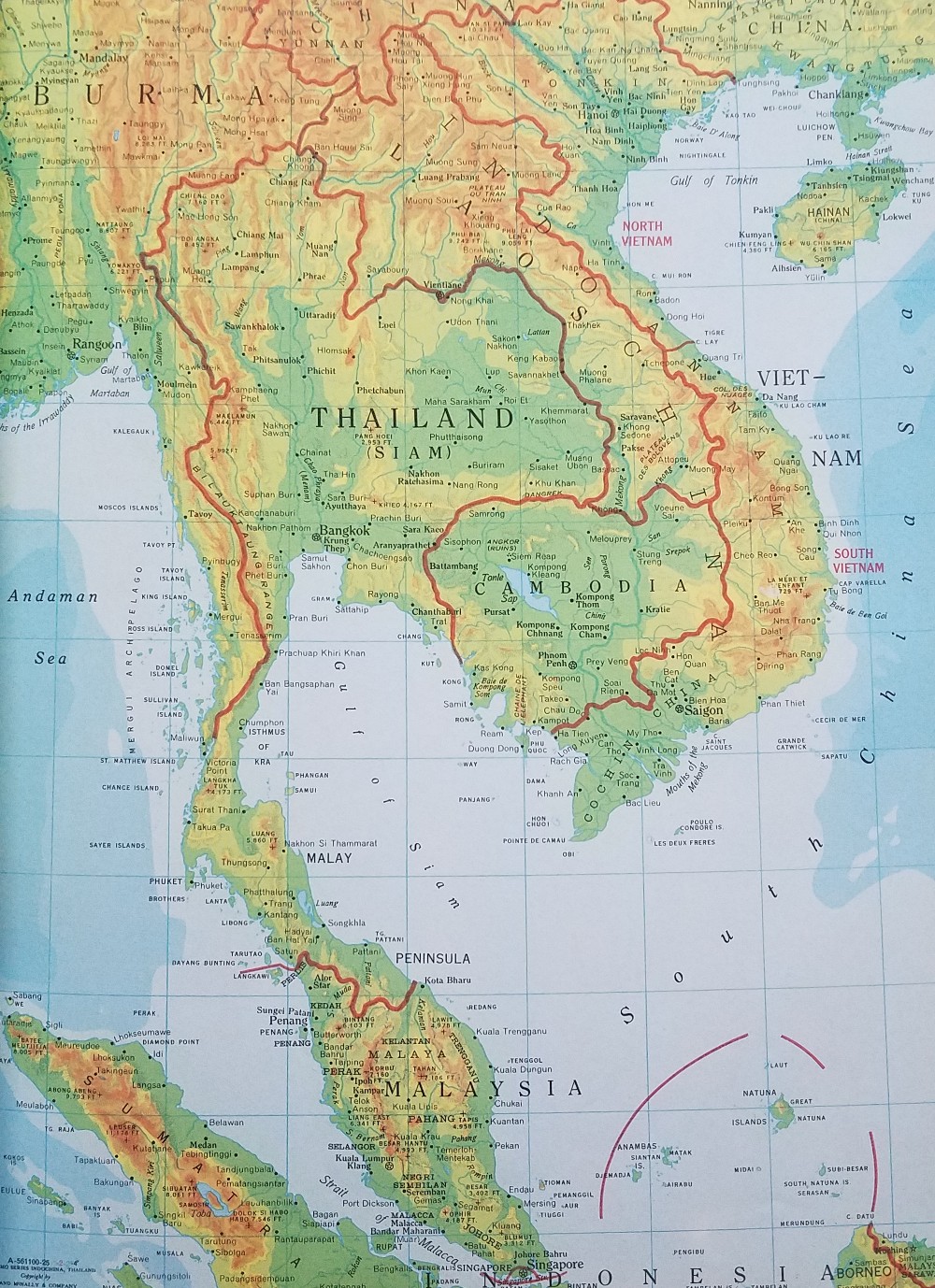

l: Prince Sihanouk in Paris shortly before his ouster. R: Prime Minister Lon Nol.

l: Prince Sihanouk in Paris shortly before his ouster. R: Prime Minister Lon Nol. Suggested by Troubleshooter. Art by Gaughan

Suggested by Troubleshooter. Art by Gaughan![[March 4, 1970] Harry's Heroes (<em>Nova 1</em>, edited by Harry Harrison)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/NVFCNDXTDF1970-421x372.jpg)

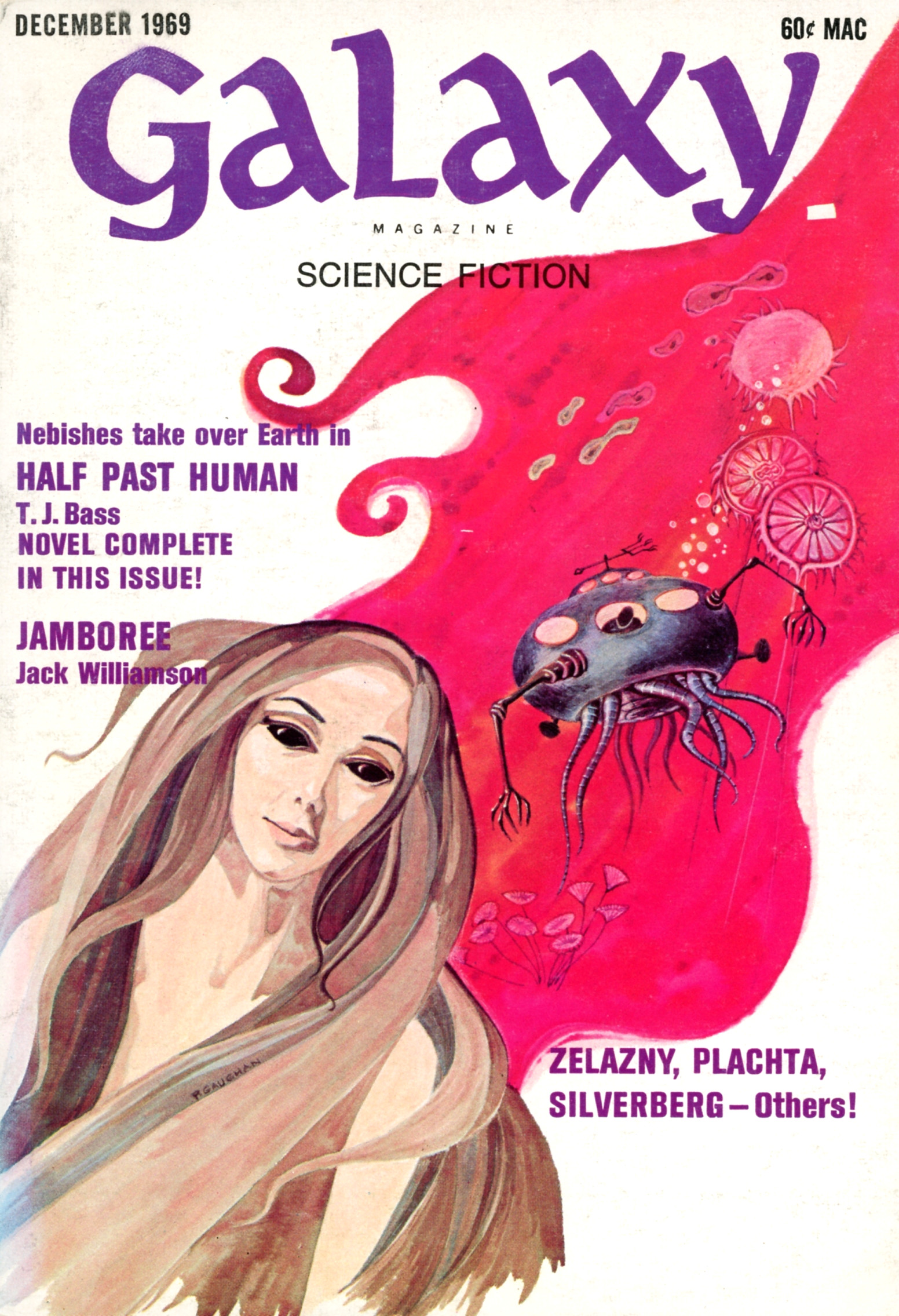

![[November 12, 1969] Leadership initiatives (December 1969 <i>Galaxy</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/691110galaxycover-672x372.jpg)

![[March 6, 1969] Different points of view (<i>Star Trek</i>: "The Cloud Minders")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/690306title1-672x372.jpg)

![[January 4, 1968] How much for that fuzzy in the window? (<i>Star Trek</i>: The Trouble with Tribbles")](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/680104title-672x372.jpg)