by David Levinson

Pressure Cooker

Every December, the American Geophysical Union holds its Fall Meeting in San Francisco. There, a number of papers are presented on a wide variety of topics in fields such as geology, oceanography, meteorology, space, and many more. Usually, it might produce a paragraph or two in the back pages of your newspaper on an attempt to predict earthquakes or some new information about the Moon, but this year’s meeting garnered headlines (hardly front page news, but more than just filler). Most of attention went to the proposal to detonate a nuclear bomb on the Moon to build up a seismological picture of our neighbor and the news that Apollo 12 was struck by lightning twice as it rose into the skies above Florida. However, it was another article that caught my eye.

Most of the column inches went to a presentation by Dr. E.D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography. He spoke of the “complex ecological questions” raised by the amount of toxic substances we’re dumping into the ocean. The use of lead in gasoline results in 250,000 tons winding up in the ocean every year, over and above the 150,000 tons that are washed there naturally. Oil tankers and other ships discharge a million tons of oil into the sea annually, with the result that there are “cases of fish tasting of petroleum.” Mackerel had to be taken off the market in Los Angeles due to unacceptable levels of DDT, while in Japan 200 people were poisoned and 40 died before authorities traced the cause to mercury discharged into Minimata Bay by a chemical company. Dr. Goldberg asked, “Will [pollution] alter the ocean as a resource? Will we lose the ocean?”

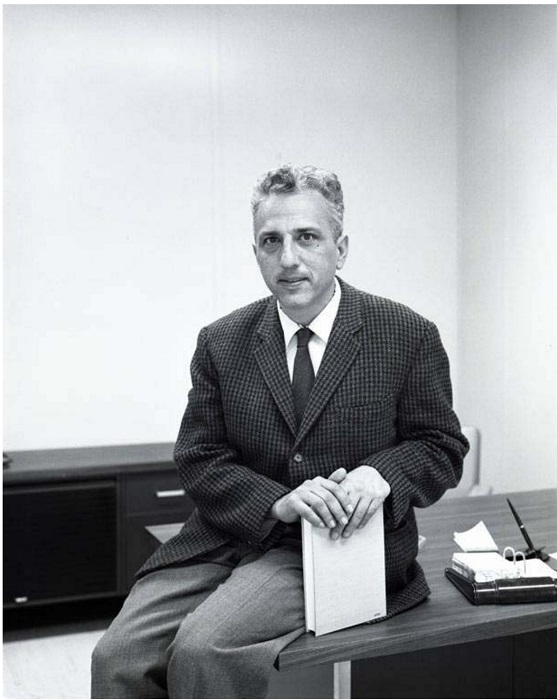

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California

Dr. Edward D. Goldberg of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in La Jolla, California

That seems like the sort of pollution we can do something about. Perhaps more concerning is the warning provided by J.O. Fletcher of the Rand Corporation. Fletcher is a retired Air Force Colonel, best known for being part of the crew that landed a plane at the North Pole and for establishing a weather station on tabular iceberg T-3 (now known as Fletcher’s Ice Island), which is still in use. He called carbon dioxide the most important atmospheric pollutant today. It is responsible for one-third to one-half of the warming thus far in the 20th century. The human contribution may surpass that of nature within a few decades. Global warming could increase the melting of the polar ice caps and change the Earth’s climate.

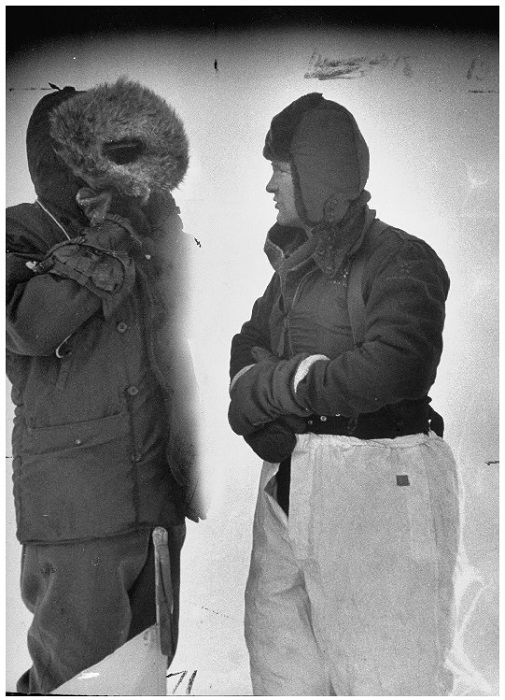

Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find.

Col. Fletcher (r.) on his ice island in 1952. This was the most recent photo of him I could find.

Fletcher’s warning was underscored by Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, who stressed the need to educate people that “man has got to change his way.” He added that global climate is going to have to become a problem that can be managed.

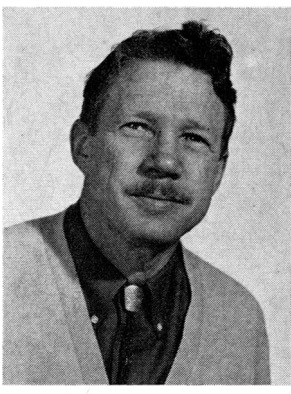

Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado

Dr. William W. Kellogg of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colorado

If the warnings of Fletcher and Kellogg sound familiar, that’s because you read it in IF first. Back in the April, 1968 issue, Poul Anderson had a guest editorial talking about the dangers of increased warming. In the August issue of the same year, Fred Pohl had an editorial warning about increasing levels of carbon dioxide. [And Isaac Asimov wrote about it back in 1958! (ed.)] An article from UPI has a much wider reach than IF, and people are more likely to take working scientists more seriously than a couple of science fiction writers. Let’s hope they pay attention.

Pressure Tests

It’s not uncommon for authors to put their characters through the wringer, pushing them to or even past their breaking point. Some would argue it’s the best way to get a story out of a setting and characters. Several of the stories in this month’s IF have taken that approach, though one subject has an awfully low tolerance for stress.

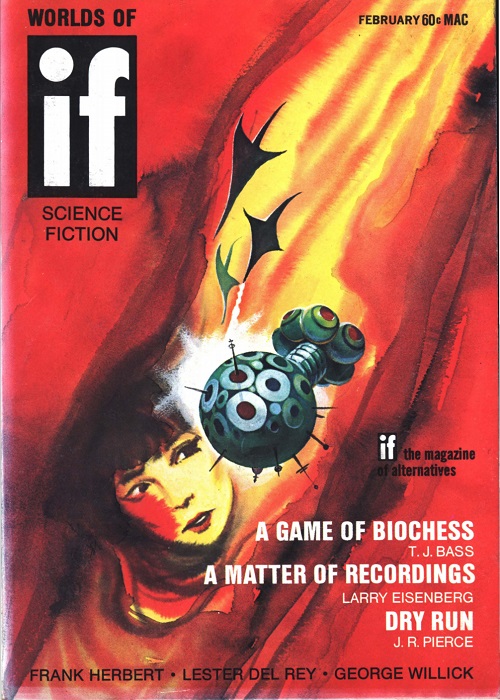

Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.

Cover by Gaughan. Supposedly suggested by Whipping Star, but it looks more like it illustrates Pressure Vessel to me.

Continue reading [January 2, 1970] Under Pressure (February 1970 IF)

![[January 2, 1970] Under Pressure (February 1970 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/IF-1970-02-Cover-500x372.jpg)