[The Journey always delights at the opportunity to broaden its coverage of current science fiction. So you can imagine how blessed we felt when we discovered a stunning new talent fresh from the city of Leningrad. We are certain you will enjoy what we hope will be the first of many articles from 'Rita…]

by Margarita Mospanova

A journey of a thousand books begins with a single page, a single sentence, a single word. And happy is the reader that can travel more than one language in his lifetime. Often, your journey happens without you taking a single step, but sometimes it can lead you halfway around the world, a single suitcase and a loudly hammering heart in tow.

The Iron Curtain may not be a physical thing but it is a perfectly tangible one nevertheless. Especially when you’ve lived your whole life on the Soviet soil and the thin trickle of Western literature could hardly slake your bookish thirst for science fiction and fantasy.

So, dear readers, you can imagine my joy when I first stepped off the ship in an American harbor and felt my literal literary horizon expanding before my eyes. A friend of a friend of a friend, that so courteously provided me with lodgings while I tried to get my wits around me and carve myself a piece of Western life, had only been too happy to encourage me.

I have to confess that in beginning I practically devoured the bookshops, without much care to what I read as long as it was halfway interesting. But that initial fever has long since faded and, several new favorite books richer, I can now take a breath and approach the shelves at a more sedate pace.

And in a corner of a small bookshop of which I have a particular fondness, I encountered several copies of this very magazine that you’re holding in your hands right now. Delighted, I read them almost in one sitting and wrote to the editor to express my appreciation. A short and exciting exchange later, I was asked to share my thoughts on the state of Soviet science fiction.

Oh my, I thought. That would be easy, I thought. There are so many to choose from, I thought.

Well, dear readers, I’m very unhappy so say that reality does so like to burn and salt the bridge before you can even step on it. Because while Soviet science fiction and fantasy books are indeed many, the number of them translated into English is… far from desirable.

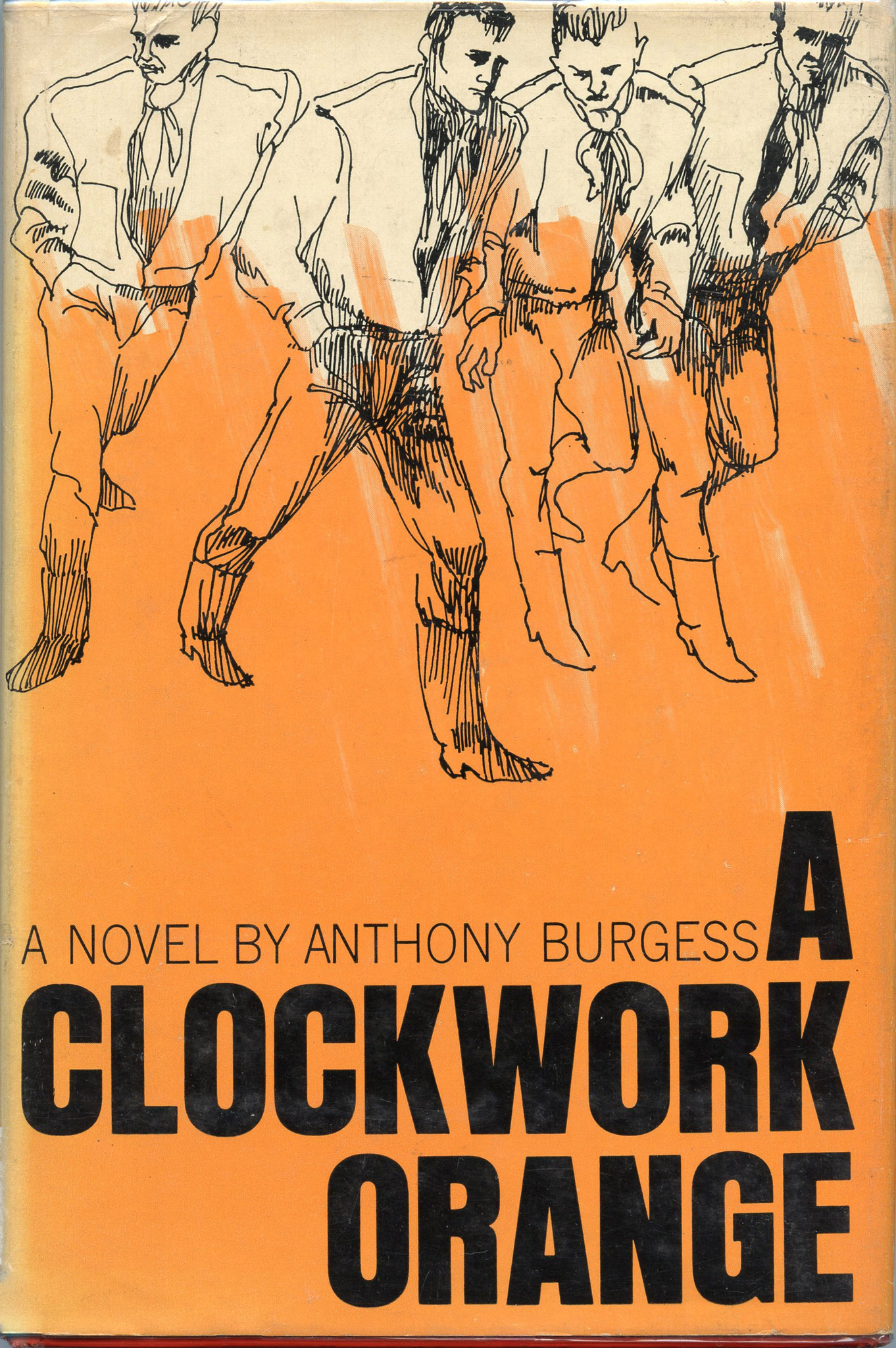

Still, Lady Fortuna was on my side. The same friend that welcomed me to America has managed to procure a translated edition of Andromeda: A Space Age Tale by Ivan Yefremov, a book I finished reading just before my rather unplanned one way journey to the west.

Almost a year ago, the Journey covered a collection of short stories by Soviet authors, featuring The Heart of the Serpent also by Ivan Yefremov. Both stories belong to the same universe, and while the timing is a bit tricky, Andromeda seems to be set slightly earlier. The novel was first published in 1957 and later translated into English in 1959 by George Hanna and printed by Moscow’s Foreign Language Publishing House. And despite my expectations, the translation itself is done fairly close to the original text, retaining its slightly cumbersome style.

The story, while not quite action driven, still has a few tense moments that might have you gripping the pages in excitement. But overall the author focuses more on the social and cultural sides of his characters’ lives, preferring to use the future Communist utopia as a background for various social and philosophical issues.

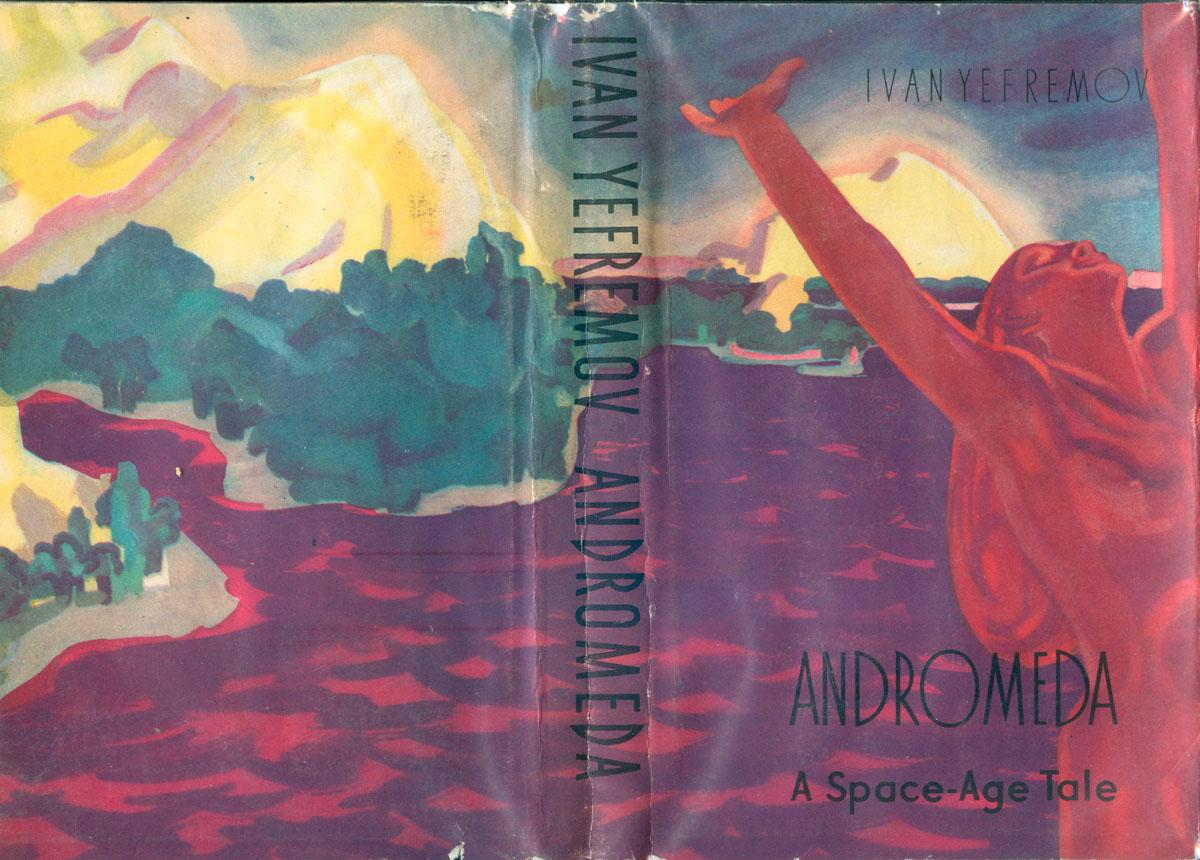

It has been several millennia since our time and the world has changed. Earth has joined the Great Circle, a collection of sentient races capable of space travel and communication, but more often than not, not yet advanced enough to meet their neighbours face to face. The spaceship travel takes centuries and faster than light speeds are still out of the scientists’ grasp.

One of the plot lines follows the crew of a spaceship sent to investigate another planet after it goes into complete and sudden radio silence. On the way back home they run out of fuel and have to make an emergency landing on a planet shrouded in heavy darkness.

I will refrain from spoiling their struggle for survival, but will say that for me that part of the novel is easily the most engaging. But that is most likely my fascination with horror stories rearing its misshapen head.

The second plot line is centered around the Director of the Outer Stations of the Great Circle (a mouthful, that’s for sure) and his life after he leaves the post to his successor and struggles to find a new job for himself. His deep and enduring love for space makes the search much more difficult than it might seem at the first glance.

The cast of principle characters also includes a historian that is also an archaeologist, a psychiatrist, a scientist, and a biologist.

In the preface the author warns the reader that the novel is full to the brim with science terms, ideas, and details. And, boy, he wasn’t kidding. If anything, he understated the technical aspects of the book. The characters spend almost half of the book going on various science-themed tangents or engaging in discussions of philosophy, sociology, or how the grass was definitely not greener back in our times.

Still, the world Yefremov built is wonderfully bright and optimistic. Despite my… differences with the regime of my home, Andromeda’s future is one I would be happy to live in.

The novel’s greatest strength and its greatest weakness, in my opinion, is its extreme attention to details. It is easy to get buried under all the little things Yefremov includes to paint the future, but the same small brush strokes eventually form a rich and fascinating world, that I, for one, would grab a chance to explore.

And I advise you to do the same. Andromeda is a book that might leave you with mixed feelings, but it will not let you remain unaffected. It challenges you to think and evaluate the world we live in today, draw your own conclusions, and imagine what your own utopian future might look like.

I give Andromeda: A Space-Age Tale four iron stars out of five.

![[August 18, 1963] The Grass is Redder in the Future (Yefremov's <i>Andromeda: A Space Age Tale</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/cover-672x372.jpg)