by Fiona Moore

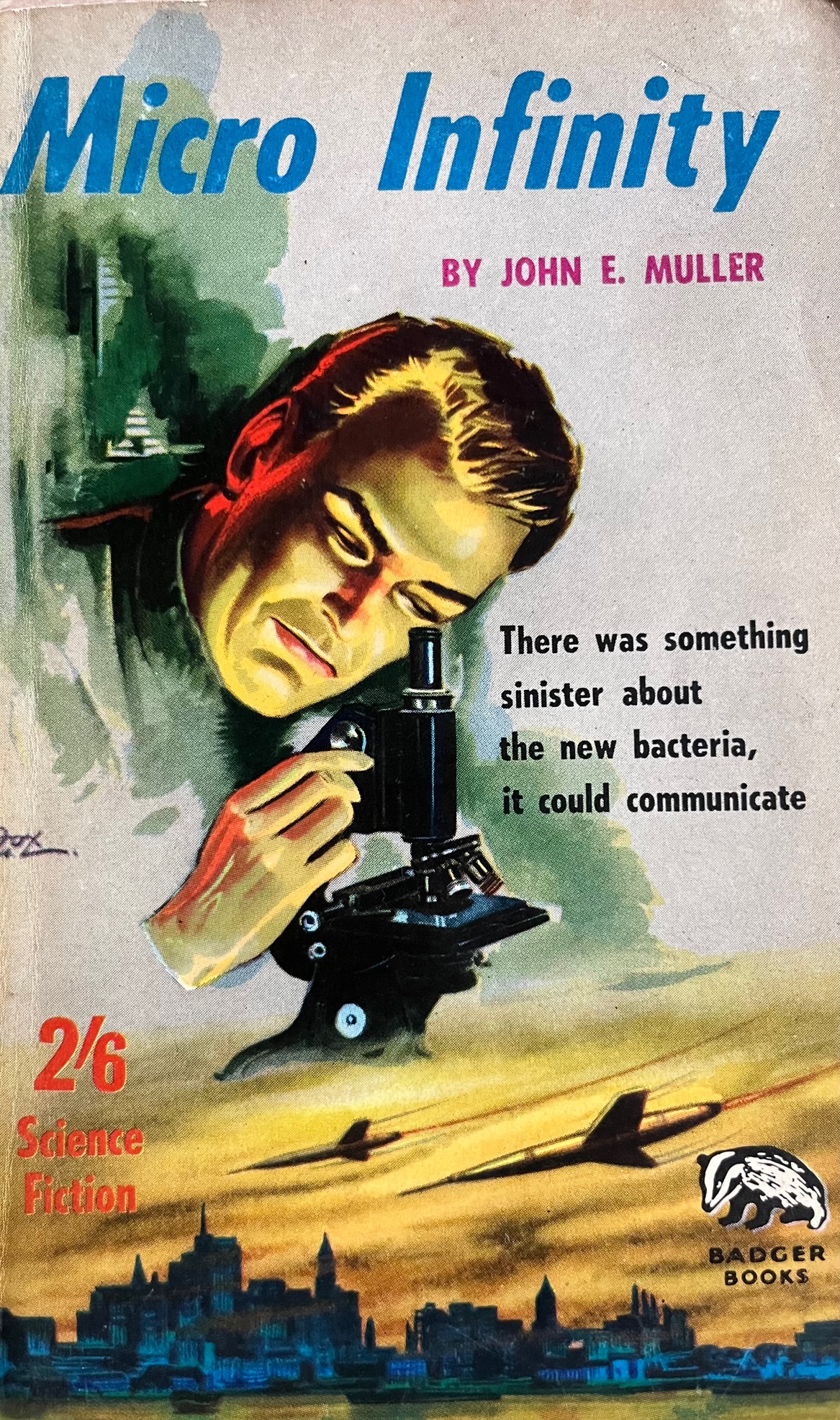

The great British pulp imprint Badger Books ceased trading earlier this year. This is a mixed blessing, but nevertheless a significant event. So it seems like a good time to provide a brief introduction for people who, like me, have a taste for schlocky and pulpy science fiction. Stuff which can make you wince and laugh by turns, but which has its heart, broadly speaking, in the right place.

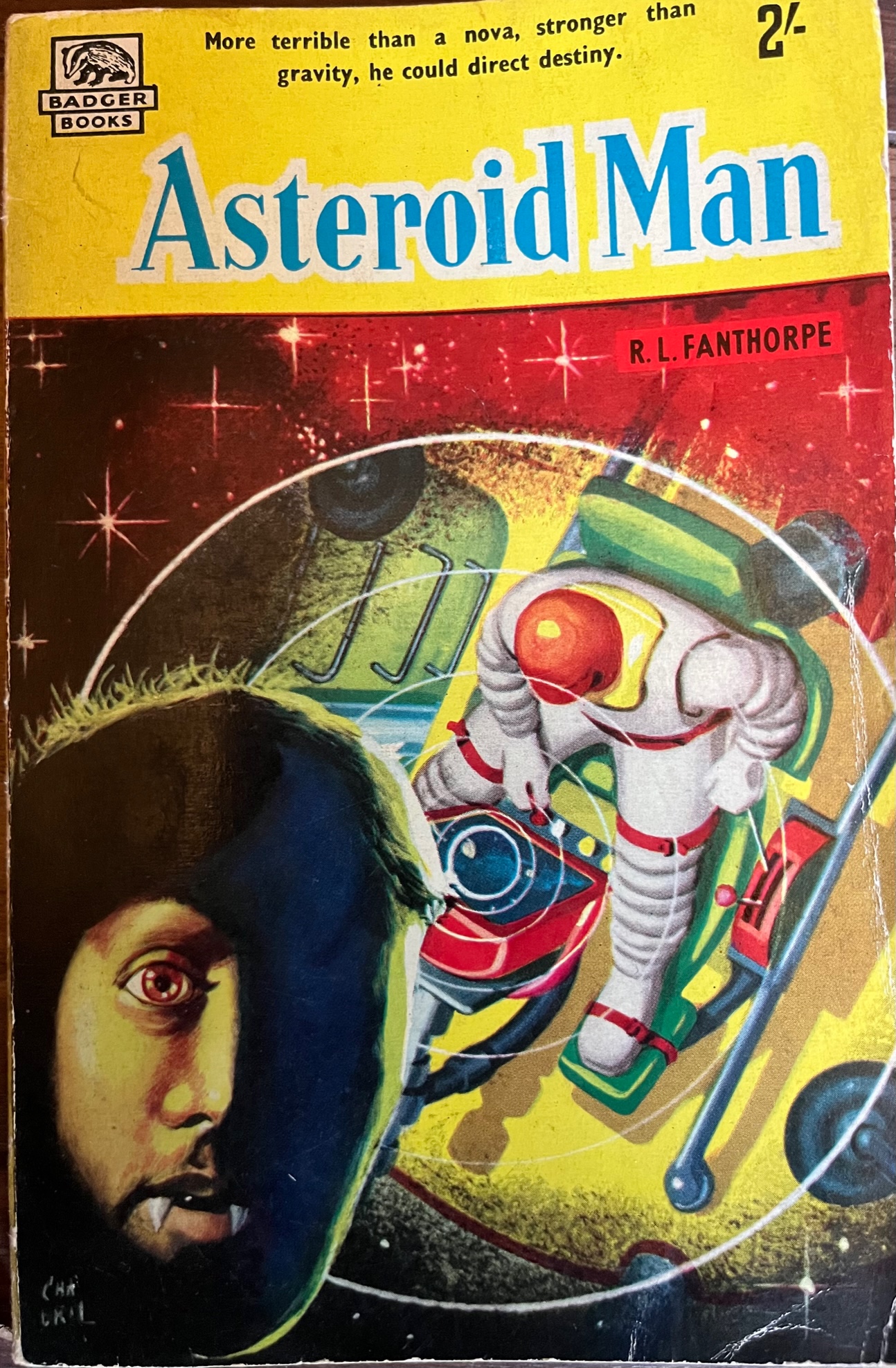

This is what we're losing.

This is what we're losing.

Badger Books was an imprint of publisher John Spencer and Co., which started off publishing pulp magazines in a variety of genres including SF, but branched out in the 1950s to publishing pulp novels. Badger Books are cheap as chips; they have no copyright pages, and they do have two to three pages of advertisements salted through the text, usually for items like good luck charms, muscle building systems or creams that magically affect your body in some way (cheekily, bust enhancement and reduction creams are usually advertised on the same page).

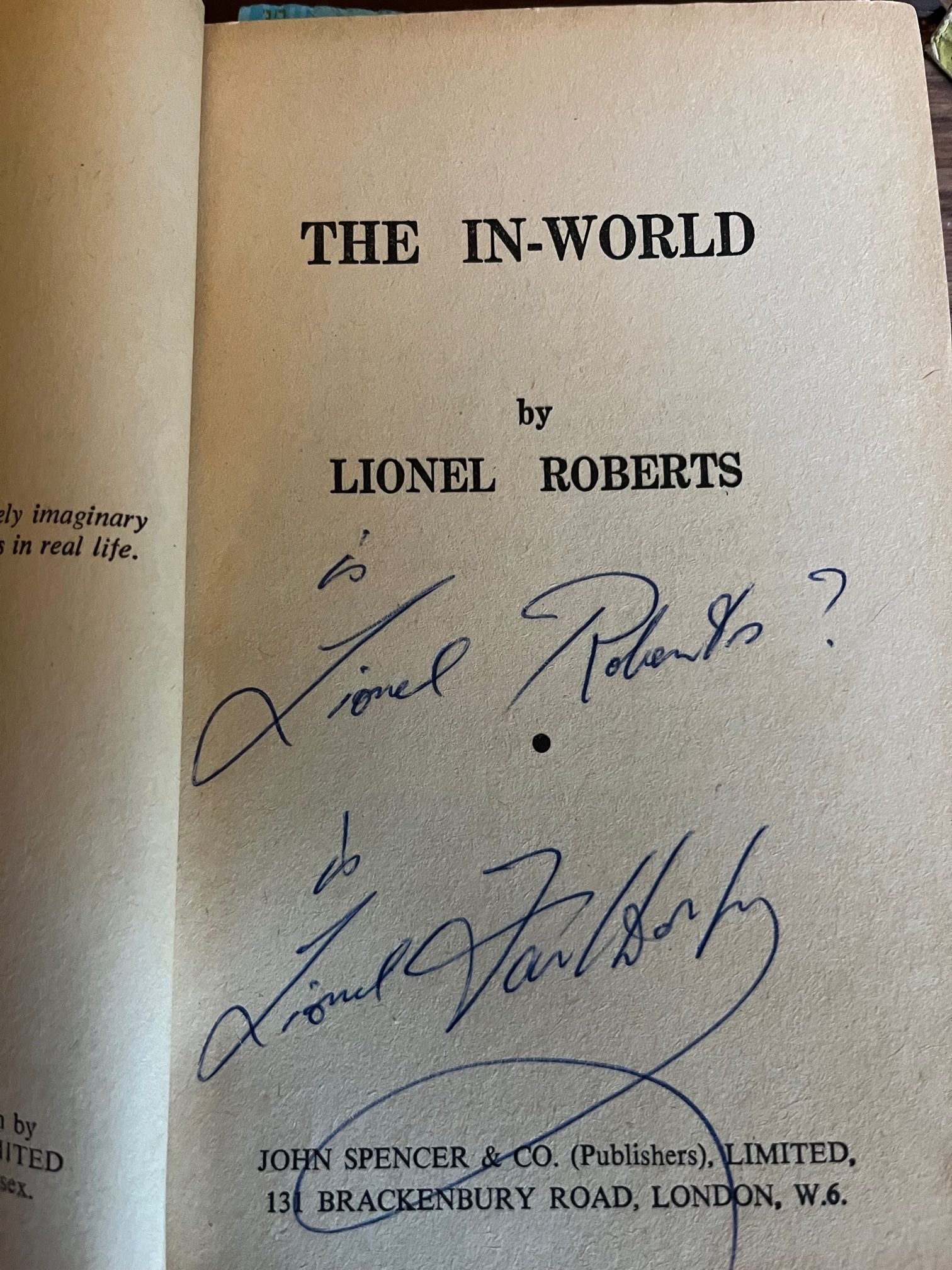

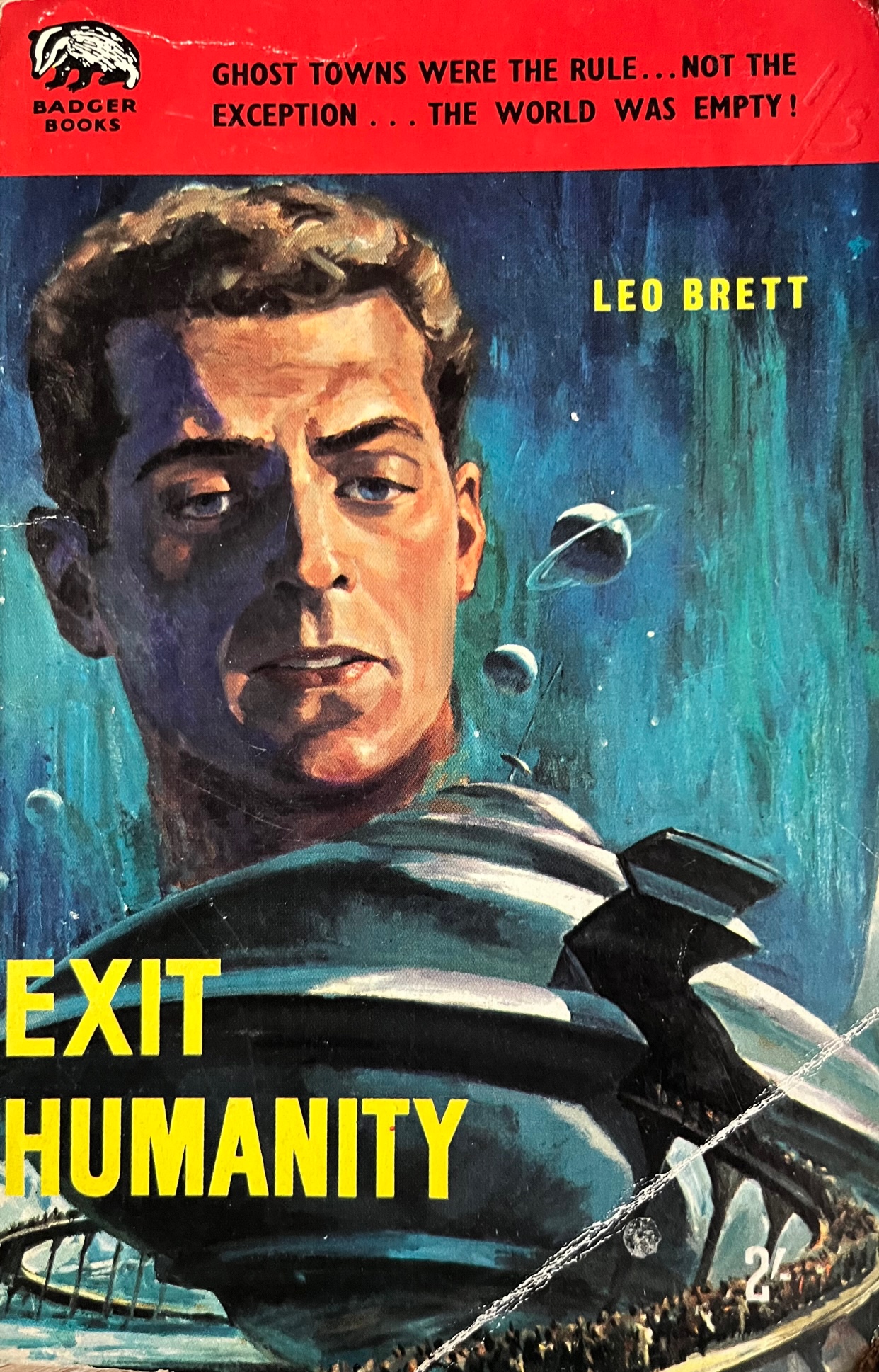

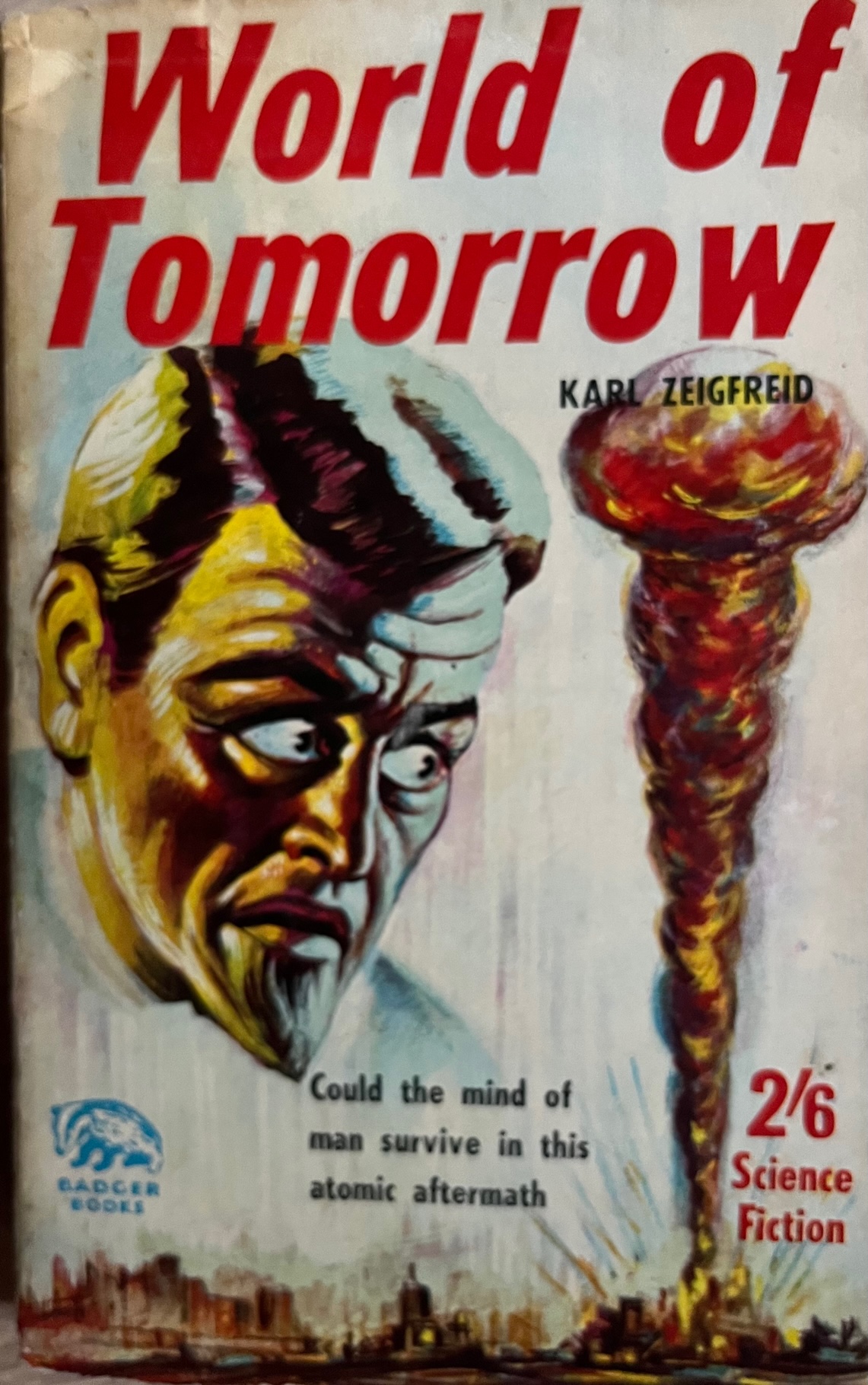

Badger’s output covers all popular genres, but the two lines most of interest to Galactic Journey readers are the science fiction and paranormal ranges, which are almost entirely written by a single person under a variety of pseudonyms. That person is Lionel Fanthorpe, schoolteacher, mystic and general eccentric, also known as Pel Torro, Leo Brett, Bron Fane, Robert Lionel Fanhope, Mel Jay, Marston Johns, Victor La Salle, Oben Lerteth, Robert Lionel, John E. Muller, Elton T. Neef(e), Phil Nobel, Peter O'Flinn, Peter O'Flynn, John Raymond, Lionel Roberts, Rene Rolant, Deutero Spartacus, Trebor Thorpe, and Karl Ziegfreid.

Even Mr Fanthorpe isn't always sure who he is

Even Mr Fanthorpe isn't always sure who he is

Fanthorpe has written as many as 250 books, by some estimates, for Badger between the early 1950s and 1967 (though some credible sources indicate his wife deserves some of the credit). Exact numbers are hard to tell, because other writers share the same pseudonyms, but he is estimated to have written one 158-page book every twelve days at the height of his productivity. Another reported detail is that the books are generated by the publisher sending Fanthorpe a copy of some cover art and asking him to write a story based on the images: sometimes, also, these images come from previously-published Ace or Avon books.

Knowledgeable readers may be able to identify the source.

Knowledgeable readers may be able to identify the source.

Sometimes these inspirations make more sense than others: Exit Humanity, for instance, is based on the cover of John Brunner’s The World Swappers, which depicts a crowd of humans going into a giant spaceship; Fanthorpe’s story involves a race of aliens deceiving humanity into thinking that the sun is about to go nova, and enticing them into what the humans think is a rescue ship that will take them to a new home. Sometimes the connection is more opaque: Space Trap, a story where two alien spaceships crash-land in medieval China, for instance, has a cover featuring a caveman and a man in an iron lung.

Yes, this really says "medieval China" to me too.

Yes, this really says "medieval China" to me too.

Reportedly Fanthorpe dictates his stories onto tape and sends them out to be typed, though this only partly explains the lackadaisical nature of his work. Character names change from page to page; subplots are abandoned or introduced depending on the needs of the word count; books change focus and plot without warning. World of Tomorrow, for instance, which opens with a pitched space battle, goes on to have the Earth stricken with plague courtesy of a misfired missile from the space battle, and then shifts to the story of an Earth astronaut who comes aboard one of the space ships and has to find his way back. The titles are often only tangentially related to the story inside the covers.

Don't expect it to make sense.

Don't expect it to make sense.

Ethnic stereotypes regrettably abound. For instance, there are the long, painful sections of Exit Humanity which feature a stereotypical Englishman, Irishman, Welshman and Scotsman musing in embarrassing dialect about the abandonment of the Earth by humanity. Arguably even worse is the homicidally excitable Chinese scientist in World of Tomorrow (named, I am very sorry to report, Hi Mi Fun), and the frequent use of the word “yellow” to describe East Asian characters in Space Trap. Asteroid Man features a Barsoom-like society divided into Black, Red, Green and White members, but the essentialism by which these are described is a little too reminiscent of the less enlightened literature of our time.

And yes, Fang Guy really *is* in the story.

And yes, Fang Guy really *is* in the story.

However, Fanthorpe is not your typical dreadful pulp writer. He is also literate, imaginative, possessed of a distinct sense of morality, and seemingly determined to have fun. There’s a lot to like in Space Trap, for instance: two sets of combatants from a galactic war between a species that look more or less like humans and a tiny insect species are stranded in medieval China. The first one deceives a local peasant boy, one Aladdin, into trying to retrieve the spaceship of the second, which looks surprisingly like an oil lamp, and whose denizens are able to win Aladdin over by seemingly doing miracles. Familiar hijinks ensue.

In Micro Infinity, a story about the human race encountering an intelligent species of bacteria with a gestalt mind, all the characters are based on ones from The Canterbury Tales, and the reader can have great fun spotting the references. At an exciting point in The In-World, Fanthorpe ratchets up the tension with, erm, a historical geography of the city of Amsterdam. For the fans, he’ll throw in mentions of the likes of Quatermass and the Pit when you least expect it. Fanthorpe will also work ideas from paranormal research even into his SF novels, for instance in Exit Humanity, where a plot point revolves around the Fortean idea that humans are naturally telekinetic.

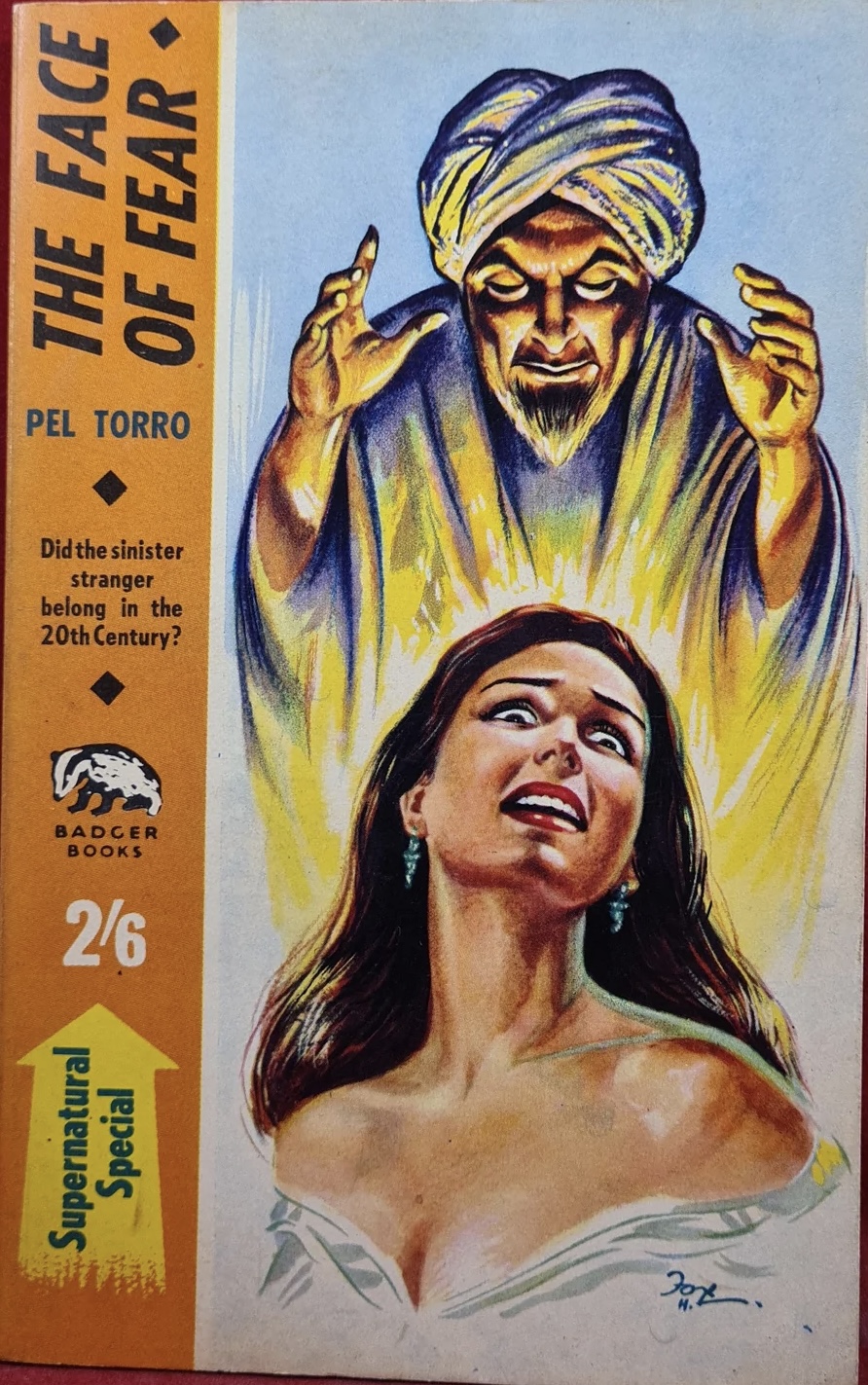

The stories can also have a strong, and generally positive, moral streak. Despite the lurid Orientalism of the cover of The Face of Fear, for instance, the story itself features an ecumenical and diverse group of paranormal researchers—- including a Church of England vicar, an Irish Catholic priest, a Buddhist, an implied-to-be-Jewish woman secretary and a Black boxer—- coming together to defeat a villain who is not, in fact, Oriental, but faking his identity. The good aliens in The Space Trap briefly provide a lecture on the evils of slavery and advise Aladdin to purchase slaves in order to free them. In World of Tomorrow, only smokers are affected by the alien plague, and humanity can be saved by people giving up that filthy habit.

He's a fake fakir.

He's a fake fakir.

On the one hand, a lot of these stories would be improved with an editor, or two, or three. On the other hand, part of what makes Fanthorpe’s work so irresistible is its spontaneity, its sense of someone throwing down words in a way that gives them pleasure, sharing jokes with readers in the know, not caring if it makes sense in the final analysis. For all their awfulness, Badger Books will definitely be missed.

Postscript: The copy of World of Tomorrow which I purchased from Porcupine Books arrived with an advertisement for family planning services tucked into the pages. Perhaps Fanthorpe readers really do have more fun?

Yes, this really happened.

Yes, this really happened.

![[August 10, 1967] Badger Books: A Farewell and an Introduction](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/IMG_6354-672x372.jpg)